Creating Racially and Economically Equitable Tax Policy in the South

reportIntroduction

“From the inception of the emerging American nation, the South is a central battleground in the struggles for freedom, justice, and equality. It is the location of the most intense repression, exploitation, and reaction directed toward Africans Americans, as well as Native Americans and working people generally. At the same time the South is the site of the most heroic resistance to these oppressive conditions.”

– Walda Katz-Fishman and Jermone Scott, The South and the Black Radical Tradition: Then and Now [1]“A fact of modern living is that the least valued carry the heaviest burden.”

– Imani Perry, As Goes the South, So Goes the Nation [2]

Southern people deserve far more than the upside-down, anti-democratic tax policies supported by many southern state lawmakers. Southern states raise less tax revenue per capita than states in other regions. They also generally fare worse on indicators of well-being, from poverty to health to educational attainment. These regional disparities are linked to southern states’ continuing underinvestment in public services, a willful austerity that inhibits opportunities for the region’s residents to thrive and are traceable to the South’s historical efforts to maintain a racial caste system. For generations, marginalized Black, Hispanic, Native and other multiracial communities in the South have resisted oppressive austerity politics with spurts of success but the dominance of racially-biased, regressive policies have mostly eclipsed these efforts.

In 2019, the South accounted for more than half of states facing the greatest levels of food insecurity, and Black families were twice as likely as whites to be affected.[3],[4] Many of these states offer the lowest unemployment benefits in the nation and are considering bills that would cut benefits even further.[5] Amid this precarious economic environment, southern states (Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana and West Virginia excepted) generally have higher uninsured rates than average and also account for most states that opted not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act even though the federal government picked up the bulk of the cost. This refusal unnecessarily leaves hundreds of thousands of low-income adults uninsured.[6] Even in states with comparatively lower uninsured rates like Kentucky and Louisiana, more than four times as many Hispanic residents are uninsured than their white counterparts.[7] Additionally, because of health care budget cuts and staff shortages, the number of rural hospital closings is on the rise in states that refuse to expand Medicaid, creating large health care deserts.[8] The lack of internet access in the Black Rural South compounds the problem by reducing the effectiveness of telehealth and virtual health appointments.[9]

The region’s negative outcomes on measures of wellbeing are the result of a century and a half of policy choices. Policymakers have many options available to make concrete improvements to tax policy that would raise more revenue, do so equitably, and generate resources that could improve schools, healthcare, social services, infrastructure, and other public resources.

|

The negative impacts of the South’s inadequate revenues also affect public education. Every southern state spends less per pupil than the national average.[12] Since greater funding is linked to higher graduation rates and increased earnings for students in adulthood, southern states’ inadequate investment in education intensifies existing income and wealth inequalities.[13] At the higher education level, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi cut per-student funding by more than 30 percent between 2008 to 2018, which resulted in higher tuition bills for public colleges.[14] This means that several states with the highest tuition increases also have the lowest average household incomes and the least ability to pay. At every turn where public policy could have a positive impact on health and economic wellbeing, southern political leaders collectively demonstrate an unwillingness to adequately invest in people and communities, creating a vicious cycle that entrenches the poor into deeper and persistent poverty.

Investment, of course, requires robust, progressive taxes. But southern politicians have long refused to create adequate and equitable tax systems, a reluctance rooted in the region’s history of protecting the white elite and suppressing Black political power, while fomenting racial animosity toward Black and brown people by poor and working-class whites who otherwise could be political allies. From overt acts of violence targeted at Black politicians who increased taxes during Reconstruction to the adoption of supermajority requirements that would block future tax increases after Black enfranchisement during the Civil Rights era, tax policies in southern states are emblematic of Black oppression and exclusion.

Remedying regressive tax policies alone will not reverse systemic injustices, but it is essential to forging a path toward a more equitable future. The South’s past and present are the nation’s past and present. This paper examines southern state tax policies through a historical and present-day racial and economic lens but political leaders in other regions of the country also create structural imbalances that perpetuate race- and class-based inequities and are not absolved from criticism. We focus on the South because the disparities in that region are often more pronounced and deserve scrutiny. This report also provides concrete recommendations for policymakers that could flip the regressive nature of these tax systems on their head.

Southern States’ Heavy Reliance on Regressive Taxes Has Negative Impacts for Racial Equity

Southern state tax systems are uniformly regressive. This means they assess a higher effective tax rate on low-income households than high-income households due to how states in this region design their tax policies. State and local governments have historically relied on three broad types of taxes – personal income, property, and consumption (sales and excise) – but these types of taxes produce very different effective tax rates by both household income level and race.[15] As the table below demonstrates, Southern states typically rely more on consumption taxes and less on income or property taxes than the national average – a pattern that worsens income and racial inequality.

Consumption taxes (i.e., sales and excise taxes) are the most regressive major tax category. These taxes tend to worsen income inequality along both racial and economic dimensions. They are based on spending, not income or ability to pay. Low-income households, a disproportionate share of whom are households of color, spend most or all of what they earn to make ends meet. This means that a larger share of their income is subject to consumption taxes than high-income households and that lower-income households, therefore, pay a higher consumption tax rate, relative to their income.

Property taxes typically apply to real estate and sometimes to motor vehicles. These taxes tend to be regressive, although to a much lesser degree than taxes on consumption. Their regressive effects are partly because home values are higher as a share of income for low-income households compared to the wealthy. Moreover, research has demonstrated that Black and Hispanic homeowners are more likely to have their property over-assessed for tax purposes and under-assessed when refinancing or selling. This housing market discrimination means Black and Hispanic homeowners often pay higher property tax rates relative to their home value than white homeowners.[16]

To counterbalance these regressive and racially inequitable taxes on consumption and property, state lawmakers who aspire to create an overall flat tax system – much less a progressive one – must include a robust and graduated personal income tax with rates that increase as incomes increase.

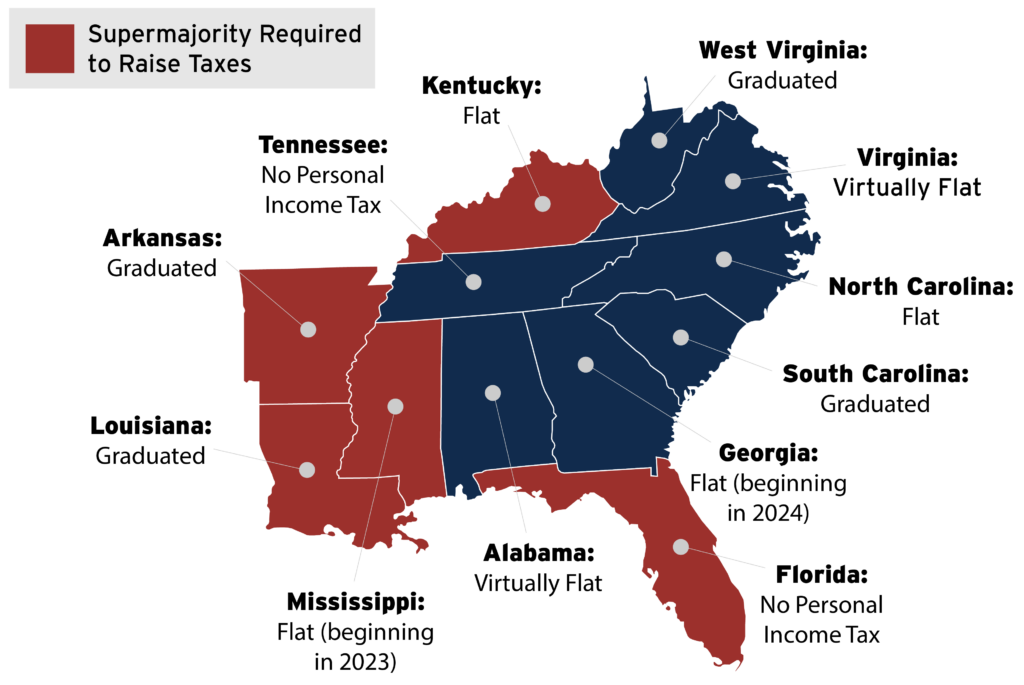

Unfortunately, few southern states have graduated income tax rates. Two states lack a personal income tax altogether (Florida and Tennessee), two have flat rate personal income taxes (Kentucky, North Carolina), two will soon have flat rate personal income taxes (Mississippi, Georgia) and two have personal income taxes that are virtually flat (Alabama, Virginia). Also of note is that in three of these states (Arkansas, West Virginia, Mississippi), lawmakers have actively tried to eliminate their income taxes within the last couple years, either in misguided attempts to grow their states’ economies or to intentionally enrich powerful interests. Further, some states (as shown in the image below) have supermajority requirements to pass tax increases. The supermajority rules limit state lawmakers’ options for raising revenue during economic downturns and protect tax breaks for special interests.

In addition to the disparate impacts of cutting public programs, inadequate state tax revenues introduce other issues that hit communities of color the hardest. This problem can be particularly acute when a state cuts funding for localities while simultaneously constraining local governments’ options for generating revenue. For example, municipal leaders should be able to raise revenue by eliminating city-level corporate tax breaks, adopting municipal income taxes or “commuter” taxes, adopting “mansion taxes” and so on, but states often bar these kinds of actions.[17] Therefore, when local policymakers face intense budget pressures, they often rely on regressive fines and fees to close the gaps. Fines and fees often provide dedicated funding for local court systems or other public services, so municipal leaders may be wary of eliminating this source of revenue, even if they recognize the regressivity of the practice. In some states, surcharges on fines and fees fund indigent defense even though imposing fines and fees often hurts the very people most in need of strong indigent defense services. South Carolina, for example, imposes assessments on top of criminal fines and Georgia imposes surcharges on bail.[18] Instead of easing financial pressures for low-income families during the pandemic and economic downturn, many municipalities have been issuing new fines to shore up their finances.[19] This practice of levying significant fines and fees is especially acute in southern states, particularly Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma, along with New York.[20] One study found that the use of fines and fees is deeply connected to the proportion of residents who are Black.[21] Not only do residents in majority-Black communities face more fines and fees than in majority-white neighborhoods, but Black residents are also more likely to be subjected to collection actions, judgment payments, and wage garnishments.[22] State and local tax structures must raise enough revenue without relying on practices that place low-income Black residents in a cycle of debt and criminalization.[23]

Supplanting Tax Revenue with Fines and Fees Increases Taxes on Poor Residents and on Black CommunitiesIn addition to the disparate impacts of cutting public programs, inadequate state tax revenues introduce other issues that hit communities of color the hardest. This problem can be particularly acute when a state cuts funding for localities while simultaneously constraining local governments’ options for generating revenue. For example, municipal leaders should be able to raise revenue by eliminating city-level corporate tax breaks, adopting municipal income taxes or “commuter” taxes, adopting “mansion taxes” and so on, but states often bar these kinds of actions.[17] Therefore, when local policymakers face intense budget pressures, they often rely on regressive fines and fees to close the gaps. Fines and fees often provide dedicated funding for local court systems or other public services, so municipal leaders may be wary of eliminating this source of revenue, even if they recognize the regressivity of the practice. In some states, surcharges on fines and fees fund indigent defense even though imposing fines and fees often hurts the very people most in need of strong indigent defense services. South Carolina, for example, imposes assessments on top of criminal fines and Georgia imposes surcharges on bail.[18] Instead of easing financial pressures for low-income families during the pandemic and economic downturn, many municipalities have been issuing new fines to shore up their finances.[19] This practice of levying significant fines and fees is especially acute in southern states, particularly Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma, along with New York.[20] One study found that the use of fines and fees is deeply connected to the proportion of residents who are Black.[21] Not only do residents in majority-Black communities face more fines and fees than in majority-white neighborhoods, but Black residents are also more likely to be subjected to collection actions, judgment payments, and wage garnishments.[22] State and local tax structures must raise enough revenue without relying on practices that place low-income Black residents in a cycle of debt and criminalization.[23] |

Southern Tax History is Rooted in Racism

The roots of the South’s current-day tax inequities can be traced to the pre-Civil War era and longstanding efforts to protect slaveholding landowners from taxation. In the early colonial era, southern colonies relied heavily on customs duties and poll taxes instead of land taxes because influential, large landholders objected to land taxes.[24] Poll taxes in the colonies were not linked to voting rights as they were in later years; the poll tax was essentially a ‘head tax’ and applied to all free men regardless of occupation or property holdings. However, poll taxes on enslaved people formed part of the property tax base since enslaved people were considered personal property. In 1774, enslaved people and servants accounted for more than a third of all “private physical wealth” in the South.[25] The historian Robin Einhorn argues that southern state constitutions adopted “uniformity clauses” in the 1820s and 1830s to protect slaveholders from paying special, higher taxes on enslaved people than on other forms of personal property.[26] Maryland first included the clause in its state constitution and other states followed including Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas. In later years, the uniformity clauses prevented states from creating special taxes on corporate assets and adopting estate taxes, inheritance taxes, and progressive rate structures.[27] Academics Katherine S. Newman and Rourke L. O’Brien claim that the uniformity clauses suppressed tax revenue altogether and added pressure to generate revenue from other sources such as license fees and other business taxes.[28]

The Civil War left widespread devastation and poverty, spurring the South to increase property taxes to fund direct aid and government programs. From as far back as Reconstruction, the American right used fiscal conservatism and the fear of higher taxes to oppose Black political power.[29] During this time, higher land taxes were key to the economic restructuring envisioned by progressive leaders. New Black political leaders raised taxes and expanded funding for infrastructure repairs and public education. Although per-capita property taxes were still low in the South compared to the North, rates doubled or more within a decade in several states.[30] Wealthy land-owning elites were then able to generate opposition to the changes from poor white farmers, who were newly affected by the higher rates.

Fighting Taxes through Both Racial Terror & Administrative Tyranny

According to the economist Trevon D. Logan, white Southerners violently resisted changes to the tax code, organizing ‘Taxpayer conventions’, rifle clubs, and other ‘civic’ organizations to intimidate Black politicians.[31] During the Vicksburg Massacre in Mississippi in 1874, the local taxpayer league opened fire on the Black militia after demanding that all Black officeholders resign.[32] Logan found that larger tax revenues were strongly correlated with an increased likelihood of violent attacks against Black policymakers and ultimately, counties with the most violence saw their taxes fall the most from 1870 to 1880. Even after property tax rates fell, landowners were doubly advantaged by having the assessed value of their properties artificially lowered during this time.[33] When federal troops retreated and the white South reasserted power and removed Black rights after Reconstruction, local property tax assessors in the Jim Crow South taxed Black property owners at higher effective rates than their white counterparts. For example, Professor Andrew W. Kahrl found that in Virginia in 1916, the average assessment on white-owned farmland was 33.1 percent of its market value compared to 45.3 percent for Black-owned land.[34]

Wealthy white southerners not only used physical violence and administrative corruption to resist tax hikes, they also swayed mainstream white public opinion against Black leaders by painting Black-led government spending as wasteful and corrupt. As the white elite campaigned against Black political power and government spending, they simultaneously fought to disenfranchise newly enfranchised Black voters. According to the scholar Vanessa Williamson, they adopted a new identity as concerned taxpayers rather than racist former slaveholders, and this new identity helped develop a political alliance with small white farmers. Thus, the idea of who is considered a ‘taxpayer’ has long been racially fraught. In 1866, white legislators fought against extending the Freedmen’s Bureau for two additional years by arguing that white taxpayers were being asked to support “lazy and worthless men.”[35] In 1892, Ida B. Wells documented newspaper coverage of a Memphis massacre that stated that the massacre was justified since the Black victims “received educational advantages at the hands of the white taxpayers.”[36] In the late 19th century, a popular Louisiana political slogan stated “‘the whites pay the taxes and the Negroes go to school” as justification for racial inequities.[37]

In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Former confederate states divided their tax receipts by race to ensure revenue for Black schools did not exceed tax contributions paid by Black taxpayers, but the opposite proved far more common. Historical tax receipts from Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia reveal that Black taxpayers regularly subsidized whites-only schools by paying more tax dollars than they received in school funding; in 1910, Black taxpayers in the South subsidized white schools to the tune of $9.5 million annually.[38] This dual tax structure demonstrates the bureaucratic exploitation that existed in tandem with the more outright forms of racial violence. And the comparatively heavy taxation on Black residents was not enough to keep up with the South’s education needs. Per-pupil expenditures in the South plummeted between 1870 and 1890 and the length of the school year was shortened by 20 percent.[39]

Fighting Taxes through the State Constitution

In Alabama, wealthy, white property owners revised the state constitution as backlash against Reconstruction-era tax reforms. Alabama has had six state constitutions, starting with the 1819 document that created the state. The 1868 version, crafted by a biracial convention during Reconstruction, aimed to raise revenue and expand state services. Less than a decade later, the 1875 constitutional convention ‘redeemers’ overthrew Reconstruction reforms by rewriting the constitution and limiting the powers of taxation by state, county, and municipal governments.[40] More specifically, the constitution adopted highly restrictive property tax limits that protected white property owners from future tax increases.[41]

In 1901, white supremacists adopted another statewide constitution that went even further to cement the dominance of white, male property owners. The best way to ensure white property owners did not pay property taxes was by disenfranchising Black residents who generally did not own a lot of property and were anxious to tax it to fund public schools.[42] The 1901 constitution, therefore, disempowered Black people, placed caps on education funding, further lowered the maximum property tax rate, and required statewide referendums for any county-level increases.[43] As a result, the tax base shifted from property taxes to personal income taxes and corporate income taxes and then, dramatically, to sales taxes in the 1930s.

The Advent of the South’s Reliance on Sales Taxes

The Great Depression wreaked havoc on the South’s already insufficient property tax base. Property values tanked but tax assessments, and subsequently tax bills, remained high year after year until property tax delinquencies grew across the region. Property tax revenue declined by 20 percent between 1930 and 1932.[44] In 1932, Mississippi became the first state to adopt a 2 percent general sales tax to raise much-needed revenue and shift taxes away from property owners; many other states throughout the nation quickly followed Mississippi’s lead, despite pushback from progressive politicians. As many southern states made it more legally and procedurally difficult to raise other forms of revenue, reliance on the sales tax grew. In 1935, Arkansas also adopted the sales tax but the revenue was used to pay down debt and further reduce property taxes.[45] Over the years, states have tended toward exempting groceries from their sales taxes to curb the steeply regressive nature of these taxes but today, five of the 13 states continuing to tax groceries either in full or in part are located in the South: Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia.[46]

From High Corporate Income Taxes to the Current Race-to-the-Bottom

Before World War II, southern states also had the highest corporate income taxes in the nation – again, as a means of facilitating lower levels of tax on landowners. After the Panic of 1837 financial crisis, states generated new revenue by expanding special corporate and license taxes. In 1842, Virginia had adopted a first-of-its-kind tax on “dividends of profit” for transportation companies and later adopted special taxes on express and telegraph companies. In 1858, Georgia began levying a gross profits tax.[47] But during the post-World War II economic expansion, state leaders slashed corporate tax rates to entice businesses to move to the South. To quote Taxing the Poor, “Historian Gavin Wright notes, “Between 1950 and 1978, the median corporate tax rate in the South went from 85 percent above, to 13 percent below, that of the rest of the country.”” Access to the new, industrialized job market was highly racialized; although Blacks accounted for nearly half the population of the Deep South in 1950, less than 1 in 5 obtained new nonagricultural jobs.[48] The corporate tax breaks benefited predominantly white shareholders who owned companies that employed predominantly white workforces.

To this day, echoes remain of the South’s history of tax policies that often ignored the need to build a civil society that worked for all its people to appease the wealthy white elite. The prioritization of corporate interests, especially at the expense of workers through right-to-work provisions and opposition to labor organization, has continued. Today, subsidies, tax credits, and tax loopholes weaken the corporate income tax base, sometimes with little to no return–on investment in the form of well-paid jobs for state residents. Nationwide, business incentives have more than tripled since 1990 despite evidence that incentives have little correlation with future economic growth.[49] North Carolina lawmakers recently agreed to eliminate the state’s corporate income tax altogether. West Virginia lawmakers just approved a $30 million “deal closing” slush fund with zero guard-rails such as reporting requirements, oversight, spending rules or opportunities for the state to recoup the funds if quality jobs do not materialize.[50] Good Jobs First found that in South Carolina, public school districts lost $423 million due to corporate tax breaks in 2019 alone, with already-poor districts that primarily serve Black and Hispanic students disproportionately bearing the brunt of the loss.[51] Although this race-to-the-bottom is not unique to the South, the South already has relatively inadequate tax revenues and this leaves even less for education, infrastructure, health care, and other programs.

Legal & Procedural Barriers to Generating Adequate Tax RevenueSimple changes in tax policy could address much of what’s wrong with southern tax codes. However, not only are current tax systems in the South inadequate and inequitable, many are also exceedingly difficult to change due to legal and procedural barriers. Legislators instituted obstacles to progressive taxation each time the political winds shifted and the wealthy, white elite worried their taxes would increase. From the ‘redemption’ era following Reconstruction to the New Deal era during the Great Depression to the 1960s civil rights era, additional barriers were put in place as racial tensions flared.[52] Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi passed their supermajority requirements directly following the Voting Rights Act of 1965, presumably to protect the existing tax rates from new Black voters. Today, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi all require supermajority votes for tax increases.[53] Florida is an example of a state with extreme limits on taxing powers. Florida lawmakers have five methods for amending the state Constitution to allow for an income tax: 1) with a three-fifths vote of the membership of both houses in the Florida legislature; 2) by a Constitutional Revision Committee which meets every 20 years to consider and propose amendments; 3) by the Taxation and Budget Commission which meets every 20 years to consider and propose amendments; 4) by voter initiative and a simple majority approval by voters to call a Constitutional Convention to consider and propose amendments; and 5) by voter initiative, as a proposed amendment to appear on the ballot; issues that raise taxes require 2/3rds support from voters while all other amendments require 3/5ths support. In short, the barriers to adopting an income tax in Florida are so high that they are nearly insurmountable even if a clear majority favored doing so. |

Policy Changes During the 2022 Legislative Session Worsened Existing Tax Structures

Whether in the South, in other states, or at the federal level, anti-tax advocates have depended on a messaging strategy that undermines the role of government and, thus, the need to raise revenue via taxation to support critical government services. Southern politicians especially used violence and other means to suppress Black political power, reduce taxes for the wealthy white elite, and underfund public services. The region's disparate outcomes on education, health and other measures of wellbeing are the result of a century and a half of policy choices.

Policymakers today are enacting tax changes that parallel the South’s long history of adopting racially inequitable policies. In 2022, many state policymakers used surplus revenues and concerns about inflation as cover to justify top-heavy tax cuts. The state surpluses are fleeting and deceptive, but several states enacted permanent, structural changes based on these temporary funds.[54]

For instance, Mississippi lawmakers chose to abandon a slightly progressive income tax bracket structure and shift to a 4 percent flat-rate income tax instead. This restructuring is heavily tilted to the wealthy and will cost the state more than $500 million annually, leaving less revenue for investments in education, infrastructure, health services, and other priorities. The table below shows that the shift will also worsen racial income inequalities as most of the tax dollars flow to white households. And due to the supermajority requirement to raise taxes, Mississippi has few options to undo this misstep when the temporary state surplus runs out and the state confronts revenue shortfalls. Further, the 4 percent flat tax bill also includes vague language directing legislators to consider additional tax cuts, and even full income tax elimination, in 2026.[55] Studies have shown that eliminating the income tax would lead to fewer state government jobs, a net decrease in population, and an overall loss in personal income, but some state leaders continue to push for this disastrous goal.[56]

Even without supermajority requirements, it is difficult to find the votes to increase taxes. Messaging from top state officials has perpetuated the myth that cutting top income tax rates primarily benefits middle-income households even when the facts prove otherwise.[57] Kentucky’s 2018 move to a 5 percent flat tax, plus the addition of some limited sales tax increases, resulted in a net tax increase for a large majority of residents. The state’s richest 5 percent of earners were the only group to receive a net tax cut on average. Yet in 2022, Kentucky passed legislation to further reduce the 5 percent rate to 4 percent in 2024, which will cost the state more than $1 billion annually in revenue and disproportionately benefit the top 1 percent. Since Black Kentuckians have been historically excluded from labor markets and wealth-building opportunities, they are disproportionately represented in the poorest quintile – an income group that will see the least benefit from recent state tax changes.

Georgia also moved to a flat tax this year, with a 4.99 percent tax rate that will reduce state revenues by over $2 billion annually when fully implemented and the benefits will again flow to top earners.[58] While the 1 percent of earners will save, on average, nearly $10,000, families at the median will save a couple hundred dollars. The flat tax bill will also exacerbate existing racial income inequalities; white households account for just 55 percent of Georgia taxpayers but will receive 66 percent of the total tax-cut value.[59]

A flat income tax with one single bracket that applies to all taxable income may seem more fair but income tax rates do not exist in isolation. Given the fact that nearly all other taxes and tax breaks are regressive, states need graduated income tax rates just to arrive at the minimal standard of tax fairness, an overall flat tax system. Since legislators would not adopt a flat rate that is higher than the existing top marginal rate, moving to a flat tax inherently cuts taxes for high-income households. The tradeoffs are simple; lawmakers can either cut back on public investments to account for the revenue loss or shift more taxes to low- and middle-income families. In either scenario, historically marginalized communities of color generally bear the brunt of these tax policy changes.

At every turn, these state lawmakers could have made more sensible policy decisions. Mississippi could have increased taxes at the top and eliminated grocery taxes altogether. Georgia could have capped the state’s costly and ineffective film tax credits, as discussed earlier in the 2022 legislative session.[60] State lawmakers could have used their temporary surpluses to meaningfully improve residents’ lives, such as Washington State’s historic investment in combatting homelessness. Instead, lawmakers in Mississippi, Kentucky, and Georgia chose to continue their legacies of prioritizing and protecting wealthy households from taxation at the expense of everyone else, and at the expense of a different future with better outcomes in the South.

Recommendations for a More Prosperous, Equitable Future

Surmounting the barriers to sustainable, adequate and progressive tax policy is worth the effort. Flipping the regressivity of southern state tax codes would have tremendous impacts on the everyday lives of low- and middle-income southerners. Southern state legislators can adopt concrete policies to help reverse the inadequate, upside-down tax codes that have been shaped over centuries. We can create the political will to drive progressive change by illustrating a bold vision of a shared, prosperous future.

While ITEP’s specific recommendations vary by state, policies common to all states include:

- Removing Legal & Procedural Barriers for Raising Revenue: Some of the policy recommendations below can only be implemented if the legal and procedural barriers described earlier are removed—such as supermajority requirements and prohibitions on state or local income taxation. Removing the barriers is a significant precondition for adopting some of the most meaningful changes – such as a graduated income tax structure.

- Higher Reliance on Graduated Income Taxes with High-Income Brackets: Adopting a graduated income tax is the most impactful and fair strategy for creating a progressive state tax system since graduated income taxes are explicitly based on one’s ability-to-pay. Due to centuries of systemic racism in labor markets, housing markets, and education systems, white families are disproportionately concentrated among the nation’s highest earners. Taxing top incomes would raise substantial revenues to fund key priorities and would also help lessen the growing racial wealth divide. As of now, most southern tax structures have flat or nearly flat income taxes, or do not tax income at all. During the 2022 legislative session, some states including Mississippi and Georgia have opted to move in the opposite direction and flatten their income tax brackets – a move that, in Mississippi, will create 75 percent more tax savings for white households than Black.[61]

- State Child Tax Credit (CTC): States should adopt a state-level CTC that would reduce child poverty and make up for inequalities in the federal CTC structure that leave out the nation’s poorest families.[62] State CTCs are especially needed in the South, a region that has the highest child poverty rates. In 2018, 45 percent of the nation’s children in poverty lived in the South.[63] The ten states with the highest child poverty rates are, in order, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, Arkansas, Kentucky, Alabama, West Virginia, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Child poverty is hard on children of all races, and Black and Hispanic children are overrepresented among the nation’s impoverished population. In the top two states, Mississippi and Louisiana, more than 60 percent of the state’s poor children are Black. State child tax credits are particularly important now since the expanded federal child tax credit has expired.

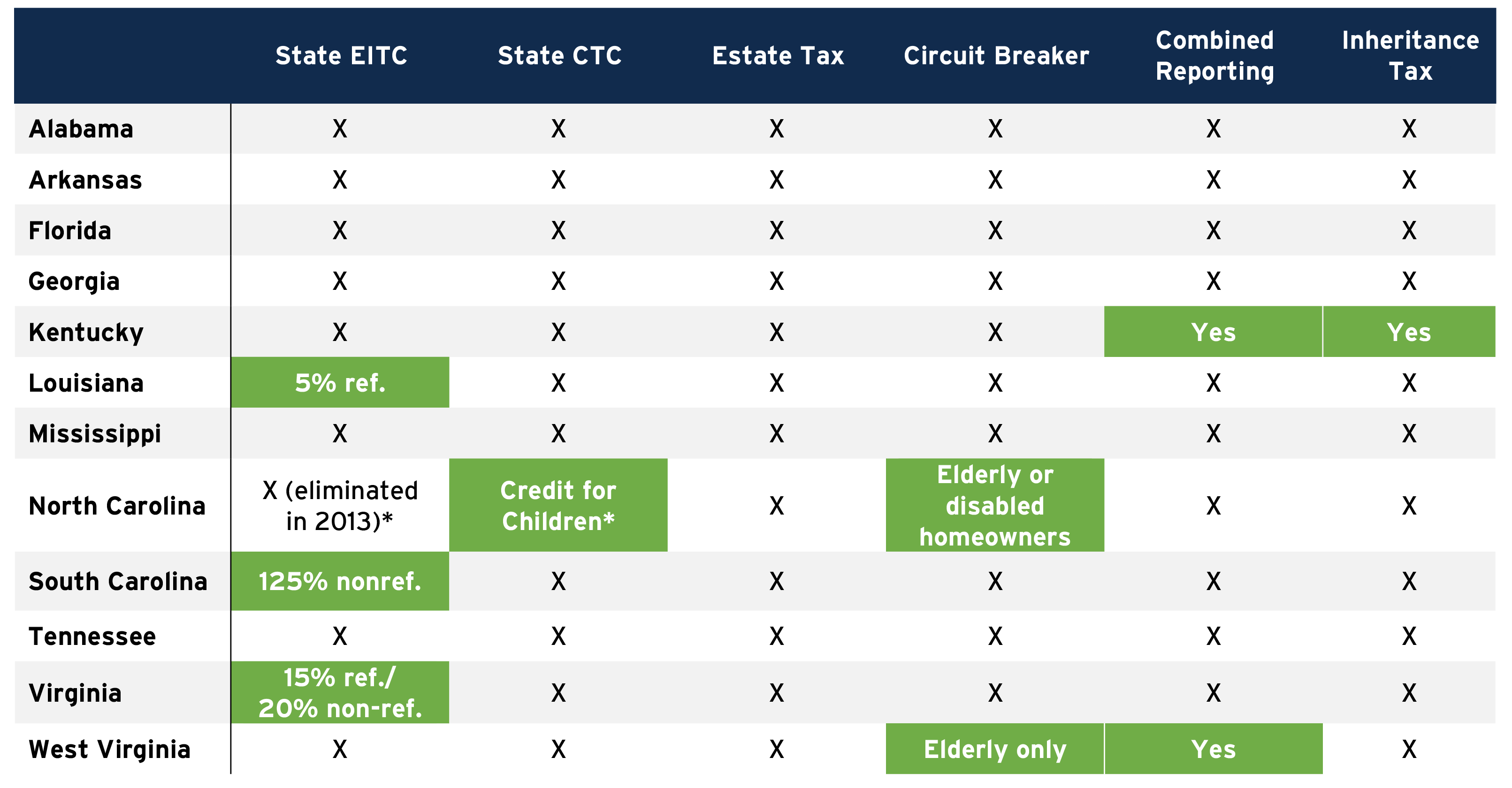

- State Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The state EITC is one of the simplest, most targeted strategies for counteracting regressive state tax codes; the tax credits reduce state income tax liability for low-income taxpayers. Since state EITCs are modeled on the federal credit, they are easy for states to administer. Nationally, 30 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have enacted state EITCs. But in the South, only three states have adopted them (Louisiana, South Carolina, and Virginia). The value of Louisiana’s credit is exceedingly low and the credits in South Carolina are non-refundable, meaning that they can only be used to offset income tax liability. On the other hand, refundable credits do not depend on the amount of income taxes paid; if the credit amount exceeds one’s income tax liability, the excess amount is refunded to the taxpayer. Refundability is a key feature for offsetting the regressive taxes that low-income families face. Fortunately, after years of tireless work, advocates in Virginia are celebrating the fact that the state’s EITC will soon be partially refundable. State EITCs help families of all races and recent studies have also found that the EITC lowers income inequality between Black and white households by 5 to 10 percent each year, though the impacts are less marked for those in deep poverty.[64] Virginia’s recent success should serve as a model for other southern state lawmakers.

- Estate Tax & Inheritance Tax: Historically, estate and inheritance taxes have played an important role in raising revenue and deconcentrating generational wealth. Until 2001, all states had an estate tax. Unfortunately, states have slowly been weakening or eliminating their estate taxes over time after President Bush signed legislation gradually phasing out the federal credit allowed for state estate taxes. The 2017 federal tax law further weakened the federal estate tax by doubling the exemption, but states with an estate tax often set their estate tax thresholds independently of the federal exemption anyway. As of now, 17 states plus the District of Columbia have an estate or inheritance tax – but this list does not include any states in the South other than Kentucky.[65] A Center for American Progress analysis found that in 2016, although six out of 10 households are white, nine out of 10 households with a net worth above the federal estate tax threshold ($12.06 million for a married couple in 2022) are white. To be clear, the overwhelming majority of white families also fall far below this threshold: only two out of every thousand estates are large enough to be subject to the federal estate tax.[66] State estate taxes kick in at a lower level, but still affect only relatively large estates. White households are four and a half times more likely to receive a gift or inheritance from family members than Black households and tend to receive much larger inheritances on average, but most inheritance gifts, for households of any race, fall below the threshold that would be subject to taxation under most state estate taxes.[67] Because wealth is so unequally distributed and so disproportionately held by white households, strengthening state estate taxes is one of the few ways to reduce both economic and racial wealth gaps.

- Property Tax Reform: Property taxes are an important source of revenue for state and local governments but they are regressive.[68] Racial bias in the housing market also creates problems with this revenue source. Historically, property taxes applied to real property and personal property, though most states no longer impose taxes on personal property beyond motor vehicles. Residential property taxes are regressive since home values are higher as a share of income for low-income families than the wealthy. Further, racial discrimination in property tax assessments and in the housing market means that Black and Hispanic homeowners pay higher property tax rates relative to home value than white homeowners. Therefore, not only has the exclusion of Black people from capital and labor markets created a racial homeownership gap, Black and Hispanic people who do become homeowners do not reap the same benefits as white homeowners on average. Nearly every state offers property tax relief through homestead exemptions that reduce the assessed value or property tax credits that directly reduce or reimburse part of the property tax bill. Homestead exemptions are generally less targeted toward low- and middle-income taxpayers than “circuit breaker” programs which are explicitly designed to offset regressivity and protect low-income taxpayers hit hardest by property taxes. The most progressive circuit-breakers are available to lower-income working-age residents (as opposed to just the elderly) and renters (as opposed to just homeowners).[69] As the racial homeownership gap has grown during the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to extend circuit breakers to renters is more important than ever – especially given new evidence that Black and Hispanic Americans pay higher rents than whites.[70],[71] As of now, just North Carolina and West Virginia have circuit-breakers in place in the South and these are limited in scope.

- Corporate Income Tax Reforms: States should consider increasing corporate income tax rates as well as broadening the corporate tax base. Corporate income taxes in the South account for approximately 1.6 percent of state and local general revenues, which is slightly less than the national average of 1.7 percent.[72] Most states levy corporate income taxes on profits earned by C corporations, though tax subsidies, tax avoidance techniques and rate reductions have eroded the state corporate tax base[73]. Because the owners of corporate stock are predominantly white and affluent, corporate tax cuts drive racial and income inequality. The wealthiest 10 percent of American households owned 89 percent of US stock in late 2021, meaning that the vast majority of Americans of any race own little in stock value.[74] Corporate tax breaks further enrich the narrow sliver who owns most of this wealth. Nationally, close to 90 percent of corporate equities and mutual fund shares are owned by white families while just 1 percent are owned by Black families and less than 1 percent are owned by Hispanic families. In addition to low corporate tax rates, many states also provide massive subsidies to corporations in a misguided attempt to attract new businesses and bolster the economy.

All of these policies could transform southern states’ ability to fund schools, healthcare, housing and other shared priorities.

Conclusion

People in the South deserve better, and there is a clear path forward.

Structural racism and austerity politics are not unique to the South. As historians have noted, anti-tax convictions find support in the North, just as leftist traditions to challenge power structures find support in the South.[75] The South boasts an incredibly rich history of grassroots organizing and resistance against oppressive conditions.[76] Yet as the target of regressive, inequitable policies, the South is a region that is inarguably beleaguered with racial oppression, poverty, and the multi-generational impacts of plantation slavery. Even today, the legacy of slavery and sharecropping contribute to persistent poverty rates, low homeownership rates, and a lack of economic development along the Black Belt and neighboring regions. The states with the highest percentages of poverty are concentrated in the South with Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, West Virginia, and Alabama topping the list. The South also accounts for states that top other indicators of financial instability such as unbanked and underbanked households.[77]

Southern states are doing far less than they could to address these inequities through their tax codes. This lack of progress is not accidental, given the fact that there is a long history of explicitly racist tax policy writing in the South, echoes of which can be seen even today. Southern politicians’ reluctance to adopt refundable tax credits or adopt adequate tax rates for high-wealth individuals and corporations exacerbate the racial inequities in the tax code. Such policymaking is also fundamentally undemocratic since it deepens inequality and wealth concentration which, in turn, concentrates the power to influence government policy and ideology. It perpetuates a system in which the voices of the wealthy and powerful have more weight.

People in the South deserve better, and there is a clear path forward. Reversing upside-down tax codes that reward corporations and households with inherited wealth can help balance the playing field and create a more equitable future for all southerners. To quote the scholar Imani Perry, “As Goes the South, So Goes the Nation.” Equitable tax policy in the South is necessary for reimagining a vision of the South as it could and should be – a prosperous and equitable region that broadens economic power for the most vulnerable, marginalized, underserved and persevering communities in the nation.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank Carl Davis for serving as a thought-partner, as well as for the careful review and research support. Thanks also to Jenice Robinson, Aidan Davis, Emma Sifre, Amy Hanauer, Neva Butkus, Marco Guzman, Dylan Grundman O’Neill, Brakeyshia Samms, and Alex Welch. Special thanks to Meg Wiehe, ITEP’s former Deputy Executive Director, and Sarah Beth Gehl, Executive Director of the Roosevelt Institute’s Southern Economic Advancement Project (SEAP).

[1] Walda Katz-Fishman and Jerome Scott, “The South and the Black Radical Tradition: Then and Now,” Association for Critical Sociology. January 2002. https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/15120585.pdf

[2] Imani Perry, “As Goes the South, So Goes the Nation,” Harper’s Magazine. July 2018. https://harpers.org/archive/2018/07/as-goes-the-south-so-goes-the-nation/

[3] Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Matthew P. Rabbitt, Christian A. Gregory, and Anita Singh. 2021. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf?v=6311.9

[4] Christianna Silva, “Food Insecurity In The U.S. By The Numbers,” National Public Radio. September 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/912486921/food-insecurity-in-the-u-s-by-the-numbers

[5] Alexa Tapia and Nzingha Hooker, “Slashing Unemployment Benefit Weeks On Jobless Rates Hurts Workers of Color”, National Employment Law Project. May 2021. https://www.nelp.org/publication/slashing-unemployment-benefit-weeks-on-jobless-rates-hurts-workers-of-color/

[6] Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid,” Kaiser Family Foundation. January 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/#:~:text=In%20states%20that%20expanded%20Medicaid,a%20result%20of%20the%20expansion.&text=In%202019%20the%20uninsured%20rate,8.3%25)

[7] Health Care, Prosperity Now Scorecard (2021), https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-issue#health/outcome/uninsured-rate

[8] Louisiana and Arkansas, both of which expanded Medicaid, have avoided hospital closures. MDC, “State of the South: Recovering Our Courage,” 2019. http://stateofthesouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/MDC_SOS_2018_final-web.pdf

[9] In the Black Rural South, 38% of African Americans report that they lack home internet access. See https://jointcenter.org/affordability-availability-expanding-broadband-in-the-black-rural-south/ and https://groundworkcollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GWC2137_Austerity-PDF-Page_Updated-Footer.pdf

[10] U.S. Census Bureau, “Census Bureau Regions and Divisions with State FIPS Codes,” April 2013. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

[11] Soo Oh, “Which states count as the South, according to more than 40,000 readers,” Vox. September 2016.

https://www.vox.com/2016/9/30/12992066/south-analysis

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, “U.S. School System Spending Per Pupil by Region,” May 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2020/comm/school-system-spending.html

[13] American University School of Education, “Inequality in Public School Funding: Key Issues & Solutions for Closing the Gap,” September 2020. https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/inequality-in-public-school-funding

[14] Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman and Matt Saenz, “State Higher Education Funding Cuts Have Pushed Costs to Students, Worsened Inequality,” October 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-higher-education-funding-cuts-have-pushed-costs-to-students

[16] Carlos Avenancio-Leon and Troup Howard, The Assessment Gap: Racial Inequalities in Property Taxation, October 2019. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3465010 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3465010

[17] Shawn Sebastian and Karl Kumodzi, Progressive Policies for Raising Municipal Revenue, Local Progress. April 2015. https://localprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Municipal-Revenue_CPD_040815.pdf

[18] Susan Herlofsky and Geoffrey Isaacman, Minnesota 's Attempts to Fund Indigent Defense: Demonstrating the Need for a Dedicated Funding Source, Mitchell Hamline School of Law, 2011. https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1405&context=wmlr

[19] Brian Highsmith (ed), Fees, Fines, and the Funding of Public Services: A Curriculum for Reform, August 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3681001 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3681001

[20] Michael Maciag, “Local Government Fine Revenues By State,” Governing. August 2019. https://www.governing.com/archive/local-governments-high-fine-revenues-by-state.html

[21] Brian Highsmith (ed), Fees, Fines, and the Funding of Public Services: A Curriculum for Reform, August 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3681001 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3681001

[22] Pamela Chan, Devin Fergus & Lillian Singh, Forced to Walk a Dangerous Line: The Causes and Consequences of Debt in Black Communities, Prosperity Now. March 2018.

[23] Meg Wiehe, “Why Local Jurisdictions’ Heavy Reliance on Fines and Fees Is a Tax Policy Issue,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2019. https://itep.org/why-local-jurisdictions-heavy-reliance-on-fines-and-fees-is-a-tax-policy-issue/

[24] Edward T. Howe and Donald J. Reeb. “The Historical Evolution of State and Local Tax Systems.” Social Science Quarterly 78, no. 1 (1997): 109–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42863678.

[25] Robin L. Einhorn, “Species of Property: The American Property-Tax Uniformity Clauses Reconsidered.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001): 985. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2697914

[26] Robin L. Einhorn, “Species of Property: The American Property-Tax Uniformity Clauses Reconsidered.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001): 974–1008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2697914

[27] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 13

[28] Ibid.

[29] Vanessa Williamson, “The Austerity Politics of White Supremacy,” Dissent Magazine. Winter 2021. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-austerity-politics-of-white-supremacy

[30] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 8

[31] Trevon Logan, Whitelashing: Black Politicians, Taxes, and Violence, June 2019. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3412688

[32] Vanessa Williamson, “The Austerity Politics of White Supremacy,” Dissent Magazine. Winter 2021. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-austerity-politics-of-white-supremacy

[33] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 10

[34] Andrew W Kahrl. “The Power to Destroy: Discriminatory Property Assessments and the Struggle for Tax Justice in Mississippi.” The Journal of Southern History 82, no. 3 (2016): 585. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43918668

[35] Dorothy A Brown, “Race and Class Matters in Tax Policy.” Columbia Law Review 107, no. 3 (2007): 790–831. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40041719

[36] Camille Walsh, ““Taxpayer Dollars”: The Origins of Austerity’s Racist Catchphrase,” Mother Jones. April 2021. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2021/04/taxpayer-dollars-the-origins-of-austeritys-racist-catchphrase/

[37] Camille Walsh, “White Backlash, the ‘Taxpaying’ Public, and Educational Citizenship.” Critical Sociology. May 2016. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0896920516645657

[38] Andrew W Kahrl. “The Power to Destroy: Discriminatory Property Assessments and the Struggle for Tax Justice in Mississippi.” The Journal of Southern History 82, no. 3 (2016): 586. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43918668

[39] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 10

[40] Wayne Flint, “Alabama’s Shame: The Hisotrical Origins of the 1901 Constitution,” 2001.

https://www.law.ua.edu/pubs/lrarticles/Volume%2053/Issue%201/Flynt.pdf

[41] Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicholas Johnson and Erica Williams, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. November 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy

[42] National Public Radio, “Effort To Scrap Alabama's Constitution,” February 2009. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=100691170

[43] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 37

[44] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 21

[45] Newman Katherine S, O’Brien Rourke L. Taxing the Poor: Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011, p. 38

[46] Eric Figueroa and Julian Legendre, “States That Still Impose Sales Taxes on Groceries Should Consider Reducing or Eliminating Them,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. April 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-that-still-impose-sales-taxes-on-groceries-should-consider

[47] Edward T. Howe and Donald J. Reeb. “The Historical Evolution of State and Local Tax Systems.” Social Science Quarterly 78, no. 1 (1997): 109–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42863678.

[48] Gavin Wright, “Southern Business and Public Accommodations: An Economic-Historical Paradox,” April 2008. https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Workshops-Seminars/Economic-History/wright-111205-3.pdf

[49] Timonthy J. Bartik, “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Off elopment Offered by State and Local Go y State and Local Governments in the ernments in the United States,” W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, January 2017. https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1228&context=reports

[50] Douglas Soule, “West Virginia’s new business incentive fund comes with $30 million and no guardrails,” Mountain State Spotlight, July 2021. https://mountainstatespotlight.org/2021/07/12/west-virginia-deal-closing-fund/

[51] Christine Wen, Kasia Tarczynska, and Greg LeRoy, “The Revenue Impact of Corporate Tax Incentives on South Carolina Public Schools,” Good Jobs First. September 2020. https://goodjobsfirst.org/sites/default/files/docs/pdfs/Revenue%20Impact%20on%20SC%20Schools.pdf

[52] Rourke L. O’Brien, “Redistribution and the New Fiscal Sociology: Race and the Progressivity of State and Local Taxes,” American Journal of Sociology. January 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6101670/

[53] National Conference of State Legislatures, “Supermajority Vote Requirements to Pass the Budget,” November 2018. https://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/supermajority-vote-requirements-to-pass-the-budget635542510.aspx

[54] Neva Butkus, “The New Trend: Short-Sighted Tax Cuts for the Rich Will Not Grow State Economies,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2022. https://itep.org/the-new-trend-short-sighted-tax-cuts-for-the-rich-will-not-grow-state-economies/

[55] Taylor Vance, “State economists predict long-term revenue loss under House tax plan,” Daily Journal. February 2022. https://www.djournal.com/news/state-news/state-economists-predict-long-term-revenue-loss-under-house-tax-plan/article_33511e95-0875-52a7-9170-1317fa61fe12.html

[56] One Voice, “Mississippi Deserves Better: Why eliminating the state income tax is wrong for Mississippi,” March 2021. http://onevoicems.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ITE-FACTSHEET-1-.pdf-.pdf

[57] Kamolika Das, “Some Lawmakers Continue to Mythologize Income Tax Elimination Despite Widespread Opposition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2022. https://itep.org/some-lawmakers-continue-to-mythologize-income-tax-elimination-despite-widespread-opposition/

[58] Danny Kanso, “New Tax Plan Risks State’s Long-Term Fiscal Health, Worsens Income and Racial Inequities,” Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, May 2022. https://gbpi.org/new-tax-plan-risks-states-long-term-fiscal-health-worsens-income-and-racial-inequities/

[59] ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model, which works on a very large, stratified sample of tax returns and other data, aged to the year being analyzed. This is the same kind of tax model used by the U.S. Treasury Department, the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office.

[60] Danny Kanso, “Georgia Tax Breaks Don’t Deliver,” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, February 2021. https://gbpi.org/georgia-tax-breaks-dont-deliver/

[61] ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model

[62] The American Rescue Plan expanded the federal CTC by making it fully refundable and available to nearly all families, but this was a temporary change.

[63] Children’s Defense Fund, “The State of America's Children 2020,” 2020. https://www.childrensdefense.org/policy/resources/soac-2020-child-poverty-tables/

[64] Bradley Hardy, Charles Hokayem, and James P. Ziliak, “Income inequality, race, and the EITC,” University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, October 2021. https://ukcpr.org/sites/ukcpr/files/research-pdfs/DP2021-10.pdf

[65] Elizabeth McNichol and Samantha Waxman, “State Taxes on Inherited Wealth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-taxes-on-inherited-wealth#:~:text=Appendix%3A%20States%20With%20Estate%20or%20Inheritance%20Taxes&text=(See%20Table%203.),to%20the%20federal%20estate%20tax.

[66] Seth Hanlon and Alexandra Thornton, "A Windfall for Wealthy Heirs," Center for American Progress. September 2017. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/windfall-wealthy-heirs/

[67] Hannah Thomas, Tatjana Meschede, Alexis Mann, Janet Boguslaw, and Thomas Shapiro, “The Web of Wealth: Resiliency and Opportunity or Driver of Inequality?.” Institute on Assets and Social Policy. July 2014. https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/leveraging-mobility/web-of-wealth.pdf.

[68] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “How Property Taxes Work,” August 2011. https://itep.org/how-property-taxes-work/

[69] Aidan Davis, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers in 2019,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2019. https://itep.org/property-tax-circuit-breakers-2019/

[70] Jason Lalljee, “The homeownership gap between Black and white Americans hasn't been this wide in 100 years,” Insider. January 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/homeownership-gap-black-white-buyers-bigger-in-2020-than-1900s-2022-1

[71] Khristopher J. Brooks, “People of color face higher rental costs than White Americans, Zillow finds,” CBS News, April 2022. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/zillow-black-renters-hispanic-security-deposit/

[72] Tax Policy Center, “State and Local General Revenue, Percentage Distribution,” August 2021. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/state-and-local-general-revenue-percentage-distribution

[73] Economic Policy Institute, “State corporate income tax revenues have eroded sharply in recent decades,” April 2022. https://www.epi.org/press/state-corporate-income-tax-revenues-have-eroded-sharply-in-recent-decades/

[74] Robert Frank, “The wealthiest 10% of Americans own a record 89% of all U.S. stocks,” CNBC. October 2021.

[75] Noam Maggor, “We Can’t Blame the South Alone for Anti-Tax Austerity Politics,” Jacobin. November 2021.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/11/austerity-anti-tax-south-northeast-slavery

[76] Walda Katz-Fishman and Jerome Scott, “The South and the Black Radical Tradition: Then and Now,” January 2002. https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/15120585.pdf

[77] Financial Assets & Income, Prosperity Now Scorecard (2021), https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-issue#finance/outcome/income-poverty-rate