Higher Education Income Tax Deductions and Credits in the States

reportDownload detailed appendix with state-by-state information on deductions and credits (Excel)

Every state levying a personal income tax offers at least one deduction or credit designed to defray the cost of higher education. In theory, these policies help families cope with rising tuition prices by incentivizing college savings or partially offsetting the cost of higher education during, or after, a student’s college career.

Interest in using the tax code to make higher education more affordable has grown in recent years as state funding has been cut and more of the cost of obtaining a postsecondary education has been passed along to students. Between the 2007-08 and 2014-15 school years, tuition at four-year public colleges rose by 29 percent while state spending per student fell by 20 percent.[1]

In many cases, however, the benefits of higher education tax breaks are modest. Since they tend to be structured as deductions and nonrefundable credits, many of these tax provisions fail to benefit to lower- and moderate-income families. These poorly targeted tax breaks also decrease the amount of revenue available to support higher education. And worse yet, they may actually provide lawmakers with a rationale for supporting cuts in state aid to university and community colleges.

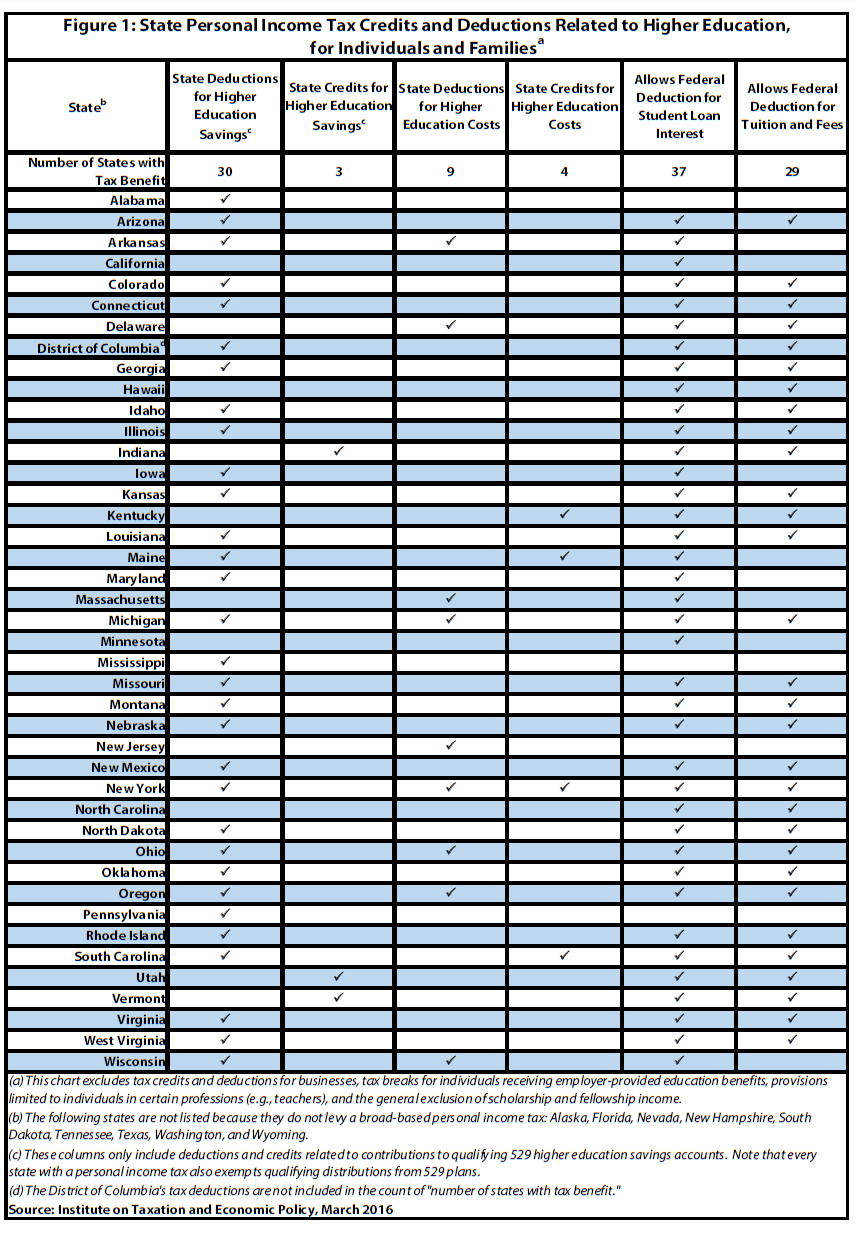

This brief explores state-level income tax breaks available to families who wish to save for higher education or who are currently making tuition, student loan and other payments for themselves or a dependent. Figure 1 provides an overview of the states offering these tax breaks, and a detailed appendix describes the specific tax deductions and credits that exist in each state.

Tax breaks for higher education savings (529 Plans)

529 plans were first introduced at the state level as a way to incentivize saving for future college costs, and later the federal government passed legislation exempting 529 contributions and earnings from the federal income tax. The plans are savings vehicles operated by states or educational institutions with tax advantages and other potential incentives that make it easier to save for college. [2] Contributions to, and distributions from, a 529 plan are not subject to federal or, in many cases, state income taxes when they are used for qualified expenses (for example, tuition, fees, books, room and board, and computer technology and equipment used for educational purposes). Additionally, any contributions to a 529 plan are not subject to the federal gift tax as long as the total amount of the contribution is less than $14,000.

Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia offer income tax credits or deductions for contributions to 529 college saving plans and exempt qualified distributions (or withdrawals) from 529 plans (see Figure 1). The other eight states levying personal income taxes exempt qualified distributions but offer no tax benefit for contributions. Of the states which offer these tax breaks:

- Thirty states and the District of Columbia offer deductions for contributions made to 529 plans. Most of these deductions are only available for contributions made to in-state plans, though six states (Arizona, Kansas, Maine, Missouri, Montana and Pennsylvania) allow a deduction for contributions made to any state’s 529 plan.[3]

- Three states (Indiana, Utah, and Vermont) offer credits for contributions made to 529 plans. All of these credits are nonrefundable.

- Every state that levies a personal income tax exempts qualified distributions from 529 plans. With the exception of Alabama, this exemption is allowed regardless of whether the 529 plan is based in-state or outside of the state.[4] (The eight states that exempt qualified distributions but offer no credit or deduction for contributions are California, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, and North Carolina.)[5]

The value of these various deductions and credits varies significantly from state to state. Rhode Island, for example, offers a deduction for 529 contributions that is capped at just $500 per taxpayer ($1,000 for married couples). Given the state’s top tax rate of 5.99 percent, a couple contributing to a 529 plan will receive no more than $60 in tax reductions in a given year because of this deduction.

Pennsylvania’s deduction of $14,000 per beneficiary per taxpayer, by contrast, may appear to be significantly more generous. In reality, however, most Pennsylvanians cannot afford to set aside that amount of money for college in a single year. If a family manages to save $3,000 for college in a given year, under Pennsylvania’s income tax that would result in no more than a $92 tax reduction.

By comparison, the tax credit structure used in Indiana is capable of providing much larger tax cuts. There, the state offers a credit equal to 20 percent of contributions (capped at a maximum benefit of $1,000 per taxpayer, per year). For a taxpayer contributing $3,000 per year to a 529 plan, this credit can provide a benefit of up to $600. That generosity comes at a high cost, however, as the Indiana Legislative Services Agency estimates the credit results in roughly $54 million in foregone state revenue each year.[6]

Tax breaks for higher education costs

Two of the most common state-level tax deductions for higher education costs actually originate at the federal level. Since most states base their income tax codes on the federal government’s definition of income, federal tax deductions for student loan interest and for tuition and fees are typically available at the state level as well.

Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia (see Figure 1) allow taxpayers to deduct student loan interest when calculating their taxable income. To qualify for the federal student loan deduction (and these state deductions), taxpayers must have a Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) of less than $80,000 ($160,000 for joint filers). This deduction is capped at $2,500.

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia also currently allow a deduction for tuition and fees. The federal deduction, and most state deductions, are capped at $4,000 per year and are subject to the same income limitations as the student loan interest deduction.[7] At the federal level, taxpayers are forced to choose between deducting their tuition payments or claiming a tax credit based on those tuition payments.[8] For most taxpayers, the tax credit option is more beneficial so the tuition deduction is less widely used (at both the federal and state levels) than would otherwise be the case. The federal tuition deduction is scheduled to expire at the end of 2016 and will likely disappear from most state tax codes as well if that expiration occurs. In the past, however, Congress has repeatedly extended the tuition deduction on a temporary basis.

In addition to the deductions for student loan interest and tuition passed through to states via linkages to federal tax law, twelve states (Arkansas, Delaware, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, and Wisconsin) offer other types of credits or deductions to help families offset higher education costs[9]:

- Three states (Kentucky, New York and South Carolina) offer tax credits against tuition payments. Kentucky’s credit is nonrefundable and is based directly on credits offered at the federal level. South Carolina offers a refundable tuition credit of its own design. And in New York, taxpayers have the option to claim a refundable tuition tax credit in lieu of an itemized deduction.

- Four states (Arkansas, Massachusetts, New York, and Wisconsin) offer tax deductions to assist with tuition payments. As in New York (see above), Arkansas provides this benefit in the form of an itemized deduction. Massachusetts offers a regular tax deduction for tuition payments that exceed 25 percent of the taxpayer’s income. And Wisconsin offers a deduction for tuition and fees that is very similar to that made available by the federal government, but with a higher maximum deduction and a somewhat lower income phase-out.

- In addition to offering the same student loan interest deduction available at the federal level, one state (Massachusetts) allows certain types of undergraduate student loan interest to be deducted without limit.

- One state (Maine) offers a credit for certain student loan repayments related to degrees completed in-state.

- One state (New Jersey) offers a flat deduction ($1,000) for each dependent that attends college full-time.

- Two states (Ohio and Oregon) allow deductions for scholarships used for room and board, the cost of which is not tax-deductible at the federal level.

- Two states (Delaware and Michigan) exempt early withdrawals from retirement accounts if the money is used for higher education.

Deductions and nonrefundable credits have limited reach

The majority of higher education tax breaks are deductions rather than credits. But credits are a better choice for middle- and lower-income residents because they reduce tax liability rather than taxable income. In states with graduated income tax rates, deductions are typically regressive since they are most valuable to those upper-income families that find themselves in higher tax brackets, and since they provide no benefit at all to those families earning too little to be subject to the income tax. For example, even with the limitations on who can claim the federal student loan deduction, much of the deduction’s benefits are still tilted toward higher-earning taxpayers.[10]

Even credits, however, are of little use to lower-income residents if they are nonrefundable—meaning that the taxpayer must earn enough to owe income tax in order to derive any benefit. And many of the credits and deductions offered by states to offset higher education costs or incentivize savings do not reach the lower end of the income scale since these residents lack the disposable income to invest in college savings vehicles or pay high tuition bills upfront.

Take, for example, Nebraska’s deduction for contributions to 529 plans. Nebraska taxpayers who contribute to 529 college saving plans based in Nebraska can deduct up to $10,000 in contributions from their state taxable income. A household with two parents and two kids must have earned at least $30,400 in 2015 to get any benefit from this deduction, thereby excluding many households in the state. To get the full benefit of the $10,000 deduction, a family of four needs to make at least $40,400 and contribute 25 percent of their earnings to the 529 plan—a near impossibility for most middle-income families. So while the deduction appears generous, it is largely accessible to higher-income households who are able to take full advantage of the tax break.

South Carolina offers a refundable tuition tax credit of up to $850, which is a better option for middle-income families than a deduction. Were this credit not refundable, a family of four would need to earn at least $35,350 to get any benefit—a requirement that would disqualify many South Carolina households. To get the full benefit of a nonrefundable credit (essentially, a reduction in tax liability by $850), a family of four would need to earn at least $50,325. South Carolina’s decision to offer a refundable credit significantly improves its effectiveness as a tool for offsetting higher education costs for those families that can least afford them.

Conclusion

Every state with a personal income tax offers at least one tax break for higher education savings, or expenses, as a tool to help offset the rising cost of higher education. The benefits of most of these tax breaks, however, are fairly modest—particularly when structured as a deduction or nonrefundable credit that provides little if any benefit to lower- and moderate-income families. While the tax code is one tool available to lawmakers interested in improving college affordability, other tools—such as general funding for higher education and needs-based financial aid grants—are more central to accomplishing this goal.

See Figure 1 for state-by-state information.

Additionally, a detailed appendix released in conjunction with this brief offers further information on each state tax deduction and credit related to higher education.

Downloadable Maps:

State Tax Treatment of Federal Deductions for Student Loan Interest and Tuition and Fees

State Tax Deductions and Credits Related to Higher Education Costs

State Tax Deductions and Credits Related to Higher Education Savings

[1] “Years of Cuts Threaten to Put College Out of Reach for More Students,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 13, 2015.

[2] “529 Plans: Questions and Answers,” www.IRS.gov, retrieved Jan. 29, 2016.

[3] “How much is your state’s 529 plan deduction really worth?,” Savingforcollege.com, February 27, 2015.

[4] “The 529 question: In-state or out-of-state?,” American Funds, November 2008.

[5] See note 3.

[6] “Indiana Handbook of Taxes, Revenues, and Appropriations: Fiscal Year 2015,” Indiana Legislative Services Agency Office of Fiscal and Management Analysis.

[7] Thirty-three of these deductions are provided in the same manner as the federal deduction, though Massachusetts and New York have somewhat more unique deductions that are described in detail in the detailed appendix accompanying this brief.

[8] The relevant federal credits are the American Opportunity Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit.

[9] This discussion excludes tax credits and deductions for businesses, tax breaks for individuals receiving employer-provided education benefits, benefits limited to individuals in certain professions (e.g., teachers and medical professionals), and the general exclusions of scholarship income, fellowship income, and qualifying distributions from 529 savings plans. Also excluded is discussion of those tax provisions designed to encourage charitable giving specifically related to higher education.

[10] “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2015-2019,” Joint Committee on Taxation, Table 3, December 7, 2015.