Read 2015 Edition of this Policy Brief Here

Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

The number of primary breadwinners relying on low-wage work to support their families has skyrocketed in recent years. Twenty-eight percent of all workers earned poverty-level wages ($11.06 per hour) or below in 2011, giving America a higher proportion of working poor than any other developed country. And more than half of the jobs created by the recovery since 2010 were low-paying, mostly in the food services, retail, and employment services industries.

This growing class of low-wage workers often faces a dual challenge as they struggle to make ends meet. First, wages are too low and growing too slowly – despite recent productivity gains – to keep up with the rising cost of food, housing, child care, and other household expenses. At the same time, the poor are often saddled with highly regressive state and local taxes, making it even harder for low-wage workers to move out of poverty and achieve meaningful economic security. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is designed to help low-wage workers meet both those challenges.

This policy brief explains how the credit works at the federal level and what policymakers can do to build upon it at the state level.

The Federal Earned Income Tax Credit

The federal EITC was introduced in 1975 to provide targeted tax reductions to low income workers, reward work, and boost incomes of low-wage workers. The EITC has been expanded numerous times, most recently in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which temporarily enhanced the EITC for families with three or more children and for married couples. Subsequent legislation enacted in early 2013 extended those enhancements through the end of 2016.

The federal EITC provided almost $63 billion worth of benefits to nearly 28 million working families and individuals in 2011. The Census Bureau estimated that 5.7 million people, including three million children, were lifted out of poverty in 2011 thanks to the federal EITC .

To encourage greater participation in the workforce, the EITC is based on earned income such as salaries and wages. For example, for each dollar earned up to $13,650 in 2014 , families with two children receive a tax credit equal to 40 percent of those earnings, up to a maximum credit of $5,460 (the maximum credit for families with three or more children is $6,143).

Because the credit is designed to provide tax relief to the working poor, there are income limits that restrict eligibility for the credit. Families continue to be eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $17,830 (or $23,260 for married-couple families). After this point, the amount families receive phases out as income increases. The credit is entirely unavailable to families with two children earning more than $43,756 if the parent is single and $49,186 if the parents are married.

For taxpayers without children the credit is less generous: the maximum credit is $496 and singles earning more than $14,590 ($20,020 for married couples without children) are ineligible. President Obama, the DC Tax Revision Commission, and members of Congress have recently proposed expansions of the EITC for childless workers.

Why a State EITC?

Why a State EITC?

The case for an EITC is even stronger at the state level. Unlike federal taxes, state and local taxes are regressive, requiring low- and moderate-income families to pay more of their income in taxes than wealthier taxpayers. According to the 2013 edition of ITEP’s Who Pays? report, the poorest twenty percent of Americans pay 11.1 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. By contrast, middle-income taxpayers pay 9.4 percent of their incomes toward those taxes, and the wealthiest one percent of taxpayers pay just 5.6 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. The high state and local tax rates faced by the poorest Americans are primarily due to the heavy use of regressive sales and property taxes. A refundable state EITC is among the most effective and targeted tax relief strategies currently used by states to reduce the unfairness of these taxes.

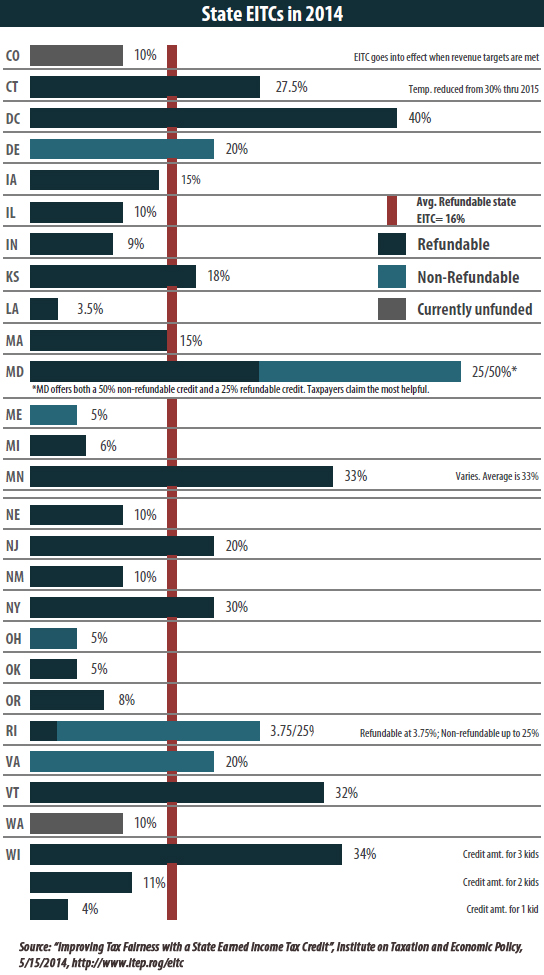

Twenty-five states (and the District of Columbia) have enacted a state EITC to reduce the unfairness of their tax systems. All of these states allow taxpayers to calculate their EITC as a percentage of the federal credit. This approach makes the credit easy for state taxpayers to claim (since they have already calculated the amount of their federal credit) and easy for state tax administrators to monitor.

However, these states vary dramatically in the generosity of their credits. The EITC provided by the District of Columbia amounts to 40 percent of the federal credit, while eight states have credits that are worth less than 10 percent of the federal credit. Moreover, four states (Delaware, Maine, Ohio, and Virginia) allow only a non-refundable credit. Non-refundable credits can only be used to offset income tax liability, even though sales and property taxes make up the vast majority of the total state and local tax bill faced by low-income working families. The nearby chart shows the EITC offered by states in 2013. (Note: Washington’s credit was passed in 2008 but has not yet been funded; Colorado’s credit is contingent on state

revenues reaching a specified threshold but should become permanent by 2015; Minnesota and Ohio’s credits are dependent on additional income criteria; Wisconsin’s credit is dependent on family size.)

Refundability is Key to EITC’s Success

The federal EITC is refundable: if the credit exceeds a taxpayer’s income tax bill, the excess amount is paid as a tax refund. The credit was designed this way because policymakers recognized that the income tax is not the only federal tax paid by low- and middle-income workers. These taxpayers usually pay much more in payroll taxes than in income taxes, for example. By making the EITC refundable, Congress ensured that it could be used to help offset all federal taxes paid, not just the income tax. Refundability is an especially important component of state EITCs as well because it allows taxpayers to use the credit to offset regressive sales, excise, and property taxes (which all working families pay).

The EITC: An Effective Anti-Poverty Tool

The EITC is widely recognized as an effective tool for preventing low-income working families from slipping into poverty. It is also important to note that the EITC is used mostly as a temporary support, helping families – including veterans making their way back into the civilian workforce – cope with temporary job loss, reduced hours, or reduced pay.

Enacting such a credit, or expanding an existing one, is also one of the most cost-effective strategies available to state lawmakers seeking to improve the fairness of state and local taxes, reward work, and help families meet their basic needs.