These Companies Are Avoiding $767 Billion in U.S. Taxes

Read the Report in PDF (Includes Company by Company Appendices)

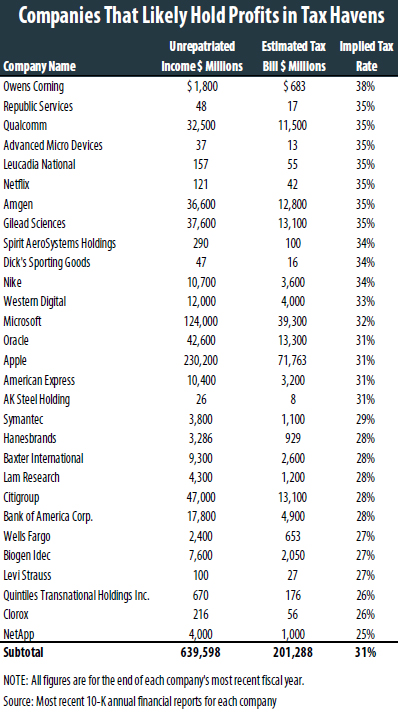

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen; apparel manufacturers Levi Strauss and Nike; the financial firm American Express; banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and lesser known companies such as Oracle and Symantec.

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen; apparel manufacturers Levi Strauss and Nike; the financial firm American Express; banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and lesser known companies such as Oracle and Symantec.

All told, Fortune 500 corporations are avoiding up to $767 billion in U.S. federal income taxes by holding more than $2.6 trillion of “permanently reinvested” profits offshore. In their latest annual financial reports, 29 of these corporations reveal that they have paid an income tax rate of 10 percent or less in countries where these profits are officially held, indicating that most of these profits are likely in offshore tax havens.

How We Know When Multinationals’ Offshore Cash is Largely in Tax Havens

Offshore profits that an American corporation “repatriates” (officially brings back to the United States) are subject to the U.S. tax rate of 35 percent minus a tax credit equal to whatever taxes the company paid to foreign governments. Thus, if an American corporation reports it would pay a U.S. tax rate of 25 percent or more on its offshore profits, this indicates it has paid foreign governments a tax rate of 10 percent or less.

29 American corporations have indirectly acknowledged paying 10 percent or less in foreign taxes on the $639 billion they collectively hold offshore. The table on the following page shows the disclosures made by these 29 corporations in their most recent annual financial reports.

Overall, the 59 companies that disclose how much they would pay upon repatriation show that they would owe an average tax rate of 28.7 percent upon repatriation, which means they have paid an average tax rate on their offshore earnings of only 6.3 percent so far.

It is almost always the case that profits reported by American corporations to the IRS as earned in tax havens were actually earned in the United States or another country with a tax system similar to ours. Most economically developed countries (places where there are real business opportunities for American corporations) have a corporate income tax rate of at least 20 percent, and typically tax rates are higher.

Countries that have no corporate income tax or a very low corporate tax — countries such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and the Bahamas — provide very little in the way of real business opportunities for American corporations like Qualcomm, Citigroup, and Microsoft. But large Americans corporations use accounting gimmicks (most of which are, unfortunately, allowed under current law) to make profits appear to be earned in tax haven countries. In fact, a 2016 Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ) examination of IRS data found U.S. corporations collectively report earning profits in Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that are more than 15 times the gross domestic products of those countries, which is clearly impossible.

Hundreds of Other Fortune 500 Corporations Don’t Disclose Tax Rates They’d Pay if They Repatriated Their Profits

Hundreds of Other Fortune 500 Corporations Don’t Disclose Tax Rates They’d Pay if They Repatriated Their Profits

At the end of 2016, 322 Fortune 500 companies collectively held a whopping $2.6 trillion offshore. (A full list of these 322 corporations is published as an appendix to this paper.)

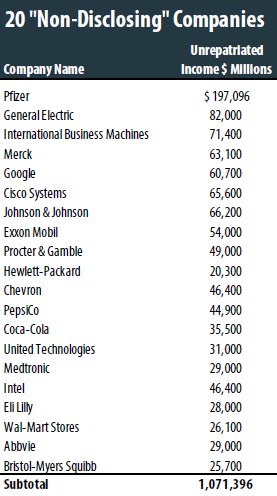

Clearly, the 29 companies that disclose paying 10 percent or less in foreign taxes on their offshore profits are not alone in shifting their profits to tax havens—they’re only alone in disclosing it. More than 80 percent of these companies — 263 out of 322 —decline to disclose the U.S. tax rate they would pay if these offshore profits were repatriated. (59 corporations, including the 29 companies shown on this page, disclose this information. A full list of the 59 companies is published as an appendix to this paper.) The non-disclosing companies collectively held $1.88 trillion in unrepatriated offshore profits at the end of 2016.

Accounting standards require publicly held companies to disclose the U.S. tax they would pay upon repatriation of their offshore profits — but these standards also provide a gaping loophole allowing companies to assert that calculating this tax liability is “not practicable.” Almost all of the 263 non-disclosing companies use this loophole to avoid disclosing their likely tax rates upon repatriation, even though these companies almost certainly have the capacity to estimate these liabilities.

Failing to disclose the tax due on offshore profits violates the spirit of the law; but failing to disclose those profits themselves appears to violate Securities Exchange Commission rules. We found five corporations that disclose having permanently reinvested earnings, but do not disclose the cumulative total of those earnings. These companies are: C.H. Robinson, Dana Incorporated, H&R Block, Jones Lang LaSalle, and Whole Foods.

Hundreds of Billions in Tax Revenue at Stake

It’s impossible to know precisely how much income tax would be paid, under current tax rates, upon repatriation by the 263 Fortune 500 companies that have disclosed holding profits overseas but have failed to disclose how much U.S. tax would be due if the profits were repatriated. But if these companies paid the same 28.7 percent average tax rate as the 59 disclosing companies, the resulting one-time tax would total $540 billion for these 263 companies. Added to the $227 billion tax bill estimated by the 59 companies who did disclose, this means that taxing all “permanently reinvested” foreign income of the 322 companies at the current federal tax rate could result in $767 billion in added corporate tax revenue.

20 of the Biggest “Non-Disclosing” Companies Hold $1 Trillion Offshore

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $1.07 trillion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 263 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

■ General Electric disclosed holding $82 billion offshore at the end of 2016. GE has subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Bermuda, Ireland and Singapore, but won’t disclose how much of its offshore cash is in these low-tax destinations.

■ Pfizer has subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, Ireland, the Isle of Jersey, Luxembourg and Singapore, but does not disclose how much of its offshore profits are stashed in these tax havens.

■ The Coca-Cola Corporation has 3 Cayman Islands subsidiaries, but the company’s limited financial disclosure doesn’t specify how much of its $35.5 billion in offshore profits are being “earned” there.

■ Merck has10 subsidiaries in Bermuda alone. It’s unclear how much of its $63 billion in offshore profits are being stored (for tax purposes) in this tiny island.

Congress Should Act

While corporations’ offshore holdings have grown gradually over the past decade, there are two reasons it is vital that Congress act promptly to deal with this problem. First, a large number of the biggest corporations appear to be increasing their offshore cash significantly. Ninety-two of the companies surveyed in this report increased their declared offshore cash by at least $500 million each in the last year alone. Thirty-four companies moved at least $2 billion offshore in 2016. And six particularly aggressive companies each increased their permanently reinvested foreign earnings by more than $5 billion in the past year. These include Apple, Intel, Microsoft, Gilead Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, and Cisco Systems.

A second reason for concern is that companies are aggressively seeking to permanently shelter their offshore cash from U.S. taxation by engaging in corporate inversions, through which companies acquire smaller foreign companies and reincorporate in foreign countries, thus avoiding most or all U.S. tax on their profits.

What Should Be Done?

Many large multinationals that fail to disclose whether their offshore profits are officially in tax havens are the same companies that have lobbied heavily for tax breaks on their offshore cash. These companies propose the government either enact a temporary “tax holiday” for repatriation, which would allow companies to officially bring offshore profits back to the U.S. and pay a very low tax rate on the repatriated income, or give them a permanent exemption for offshore income in the form of a “territorial” tax system. Either of these proposals would increase the incentive for multinationals to shift their U.S. profits, on paper, into tax havens.

A far more sensible solution would be to simply end “deferral,” that is, repealing the rule that indefinitely exempts offshore profits from U.S. income tax until these profits are repatriated. Ending deferral would mean that all profits of U.S. corporations, whether they are generated in the U.S. or abroad, would be taxed by the United States in the year they are earned. Of course, American corporations would continue to receive a “foreign tax credit” against any taxes they pay to foreign governments, to ensure profits are not double-taxed.

In addition, Congress or the Securities and Exchange Commission should require more transparency from companies on their offshore earnings. At minimum, this means removing the exemption from the current regulation that allows companies to avoid disclosure of the tax they would owe on their unrepatriated funds if they deem it not practicable to make that calculation. A more comprehensive approach would be to require companies to publicly disclose their income, tax and other financial information on country-by-country basis.

Conclusion

The limited disclosures made by a handful of Fortune 500 corporations show that corporations are brazenly using tax havens to avoid taxes on significant profits. But the scope of this tax avoidance is likely much larger, since the vast majority of Fortune 500 companies with offshore cash refuse to disclose how much tax they would pay on repatriating their offshore profits.

Lawmakers should resist calls for tax changes, such as repatriation holidays or a territorial tax system, that would reward U.S. companies for shifting their profits to tax havens. If the Securities and Exchange Commission required more complete disclosure about multinationals’ offshore profits, it would become obvious that Congress should end deferral, thereby eliminating the incentive for multinationals to shift their profits offshore once and for all.