INTRODUCTION

New Census Bureau data released this month show that the share of Americans living in poverty remains high, despite other signs of economic recovery. The national 2012 poverty rate of 15 percent is essentially unchanged since 2010 , but still 2.5 percentage points higher than pre-recession levels. This means that in 2012, 46.5 million, or about 1 in 6 Americans, lived in poverty.1 The poverty rate in most states also held steady with five states experiencing an increase in either the number or share of residents living in poverty while only two states saw a decline.2

New Census Bureau data released this month show that the share of Americans living in poverty remains high, despite other signs of economic recovery. The national 2012 poverty rate of 15 percent is essentially unchanged since 2010 , but still 2.5 percentage points higher than pre-recession levels. This means that in 2012, 46.5 million, or about 1 in 6 Americans, lived in poverty.1 The poverty rate in most states also held steady with five states experiencing an increase in either the number or share of residents living in poverty while only two states saw a decline.2

Astonishingly, state tax policies in virtually every state make this problem worse rather than better. When all the taxes imposed by state and local governments are taken into account, every state imposes higher effective tax rates on poor families than on the richest taxpayers. Despite this unlevel playing field state tax systems already create for their poorest residents, many state policymakers have recently proposed (and in some cases enacted) tax increases on the poor under the guise of “tax reform” to finance tax cuts for their wealthiest residents and profitable corporations.

There is a better approach. Just as state and local tax policies can push individuals and families further into poverty, there are tax policy tools available that can help them move out of poverty. In most states, truly remedying state tax unfairness would require comprehensive tax reform. Short of this, lawmakers should use their states’ tax systems as a means of providing affordable, effective and targeted assistance to the growing number of people living in poverty.

This report presents a comprehensive view of anti-poverty tax policies, surveys tax policy decisions made in the states in 2013, and offers recommendations every state should consider to help families rise out of poverty. States can jump-start their anti-poverty efforts by enacting one or more of four proven and effective tax strategies to reduce the share of taxes paid by low- and moderate-income families: state Earned Income Tax Credits, property tax circuit breakers, targeted low-income credits, and child-related tax credits.

STATE TAX SYSTEMS AND POVERTY

State tax systems do little to help families living in poverty. In fact, state tax systems typically make things even harder for families living on the margins. A 2013 ITEP report, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States3, found that nationwide, the poorest twenty percent of Americans paid an average 11.1 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. Middle-income taxpayers didn’t fare much better, paying an average of 9.4 percent of their incomes toward those taxes. But when it comes to the wealthiest one percent, ITEP found they paid just 5.6 percent of their incomes, on average, in state and local taxes.

The fact is that nearly every state and local tax system takes a much greater share of income from middle- and low-income families than from the wealthy. This “tax the poor” strategy is problematic because hiking taxes on low-income families pushes them further into poverty and increases the likelihood that they will need to rely on safety net programs. From a state budgeting perspective, this “soak the poor” strategy also doesn’t yield much revenue compared to modest taxes on the rich.

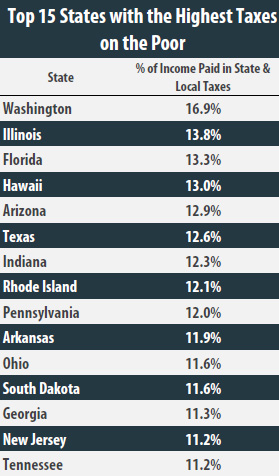

STATES WITH THE GREATEST NEED FOR IMPROVEMENT

Every state could stand to improve its tax treatment of low- and moderate-income families. However, some states have an especially great need to consider the reforms outlined in this report. The chart to the right shows the 15 states with the highest state and local taxes on the poor as a share of income. Washington State, which does not have an income tax, is the highest-tax state in the country for poor people. In fact, when all state and local sales, excise and property taxes are tallied up, Washington’s poor families pay 16.9 percent of their total income in state and local taxes. Compare that to neighboring Idaho and Oregon, where the poor pay 8.2 percent and 8.3 percent, respectively, of their incomes in state and local taxes — far less than in Washington. Illinois, which relies heavily on consumption taxes, ranks second in its taxes on the poor, at 13.8 percent. Florida— a no-income-tax state —taxes its poor families at a rate of 13.3 percent, ranking third in this dubious distinction.

It should be noted that three states — Kansas, North Carolina, and Ohio (already on this list)— enacted tax packages in 2013 that hiked taxes on low-income households beyond the already high levels shown in the chart at right.

STATE TAX STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING POVERTY

Refundable Earned Income Tax Credits

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is widely recognized as an effective anti-poverty strategy. It was introduced in 1975 to provide targeted tax reductions to low-income workers and also as an important way of rewarding work and increasing incomes.

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is widely recognized as an effective anti-poverty strategy. It was introduced in 1975 to provide targeted tax reductions to low-income workers and also as an important way of rewarding work and increasing incomes.

The federal EITC is administered through the personal income tax. To encourage greater participation in the workforce, the EITC is based on earned income such as salaries and wages. For example, for each dollar earned up to $13,430 in 2013, families with three children receive a tax credit equal to 45 percent of those earnings, up to a maximum credit of $6,044. Because the credit is designed to provide tax relief to the working poor, there are income limits that restrict eligibility for the credit. Families continue to be eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $17,530 (or $22,870 for married-couple families). Above this income level, the value of the credit is gradually reduced to zero and is unavailable when family income goes beyond the eligibility level. The credit is entirely unavailable to families with three or more children earning more than $46,227 if they are single and $51,567 if married. For taxpayers without children the credit is less generous: the maximum credit is $487and singles earning more than $14,340 ($19,680 for married couples without children) are ineligible.

The Census Bureau estimated that 5.7 million people, including three million children, were lifted out of poverty in 2011 thanks to the federal EITC.

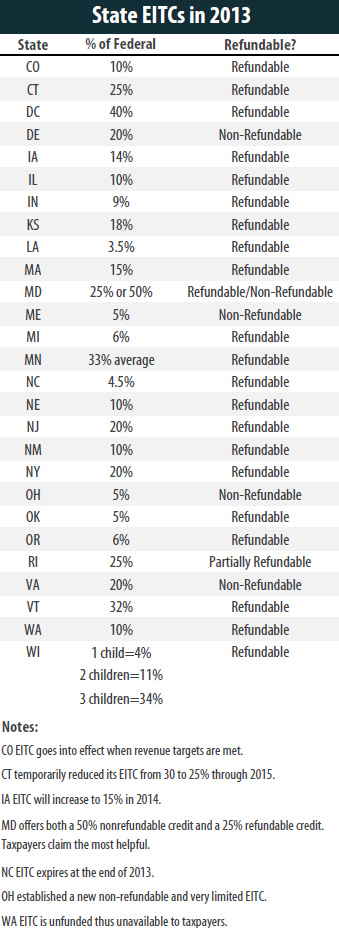

Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia(DC) have enacted state Earned Income Tax Credits based on the federal EITC. Calculating a state EITC as a percentage of the federal credit makes the credit easy for state taxpayers to claim (since they have already calculated the amount of their federal credit) and easy for state tax administrators to monitor. However, these states vary dramatically in the generosity of their credits. The credit provided by the District of Columbia amounts to 40 percent of the federal credit, while eight states will have credits worth less than 10 percent of the federal credit in 2013.

Refundability is an especially important component of state EITCs or any targeted low-income tax credit to ensure deserving families get the full benefit of the credit. Refundable credits do not depend on the amount of income taxes paid: if the credit amount exceeds your income tax liability, the excess amount is given as a refund. Thus, refundable credits are useful in offsetting the regressive nature of sales and property taxes, and can provide a much needed income boost to help families pay for basic necessities. In all but four states (Delaware, Ohio, Rhode Island and Virginia), the EITC is fully refundable. State EITCs have bipartisan support because they are easily administered and relatively inexpensive. However, EITCs are most generous to families with children. Policymakers should be aware that the EITC does little to benefit seniors and families without children because it was designed to specifically help families with children. There are other tax provisions offered by states like enhanced personal exemptions or standard deductions that are available to elderly taxpayers.

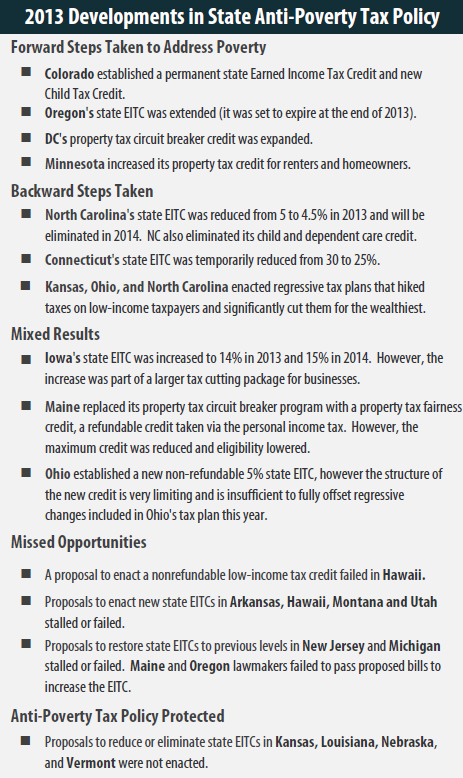

2013 EITC Developments in the States

• Colorado lawmakers enacted a permanent refundable state EITC equal to 10 percent of the federal credit (the new EITC goes into effect when revenue targets are met).

• Connecticut lawmakers temporarily reduced the state’s EITC from 30 to 25 percent of the federal credit. The credit will be restored to 30 percent in 2015.

• Iowa’s state EITC was increased from 7 to 14 percent (will go to 15 percent in 2014), however the increase was part of a tax cut package that gave profitable businesses a much larger property tax break costing 10 times more than the targeted tax cut for low-income Iowans.

• North Carolina experienced the biggest defeat to this proven tax policy. Lawmakers reduced the state EITC from 5 to 4.5 percent in 2013. They also allowed the credit to expire after this year despite passing a significant and regressive tax overhaul which increases taxes on low-income families and cuts them for wealthy households and profitable corporations.

• Ohio enacted a new limited non-refundable 5 percent state EITC as part of a larger tax package which also hiked the sales taxes, cut income tax rates, and reduced taxes on pass- through business income. The new credit is not sufficient to offset the regressive impact of the other tax changes.

• Oregon lawmakers extended the state’s EITC which had been set to sunset at the end of 2013, but did not increase the credit from 6 to 8 percent as the governor proposed.

• Proposals to eliminate or greatly reduce state EITCs in Kansas, Nebraska and Vermont were not enacted.

• Proposals to restore prior year cuts to state EITCs in New Jersey and Michigan stalled and a proposed increase to Maine’s state EITC failed.

• Proposals to enact new EITCs failed in Arkansas, Hawaii, Montana and Utah.

Recommendation: To help alleviate poverty, states with EITCs should consider increasing the percentage of the existing credit and other states should consider introducing a generous and refundable EITC.

| IMPORTANCE OF REFUNDABILITY

The hallmark of a truly effective low-income credit is that it is refundable. This means that if the amount of the credit exceeds the amount of personal income tax you would otherwise owe, you actually get money back. Refundability is a vital feature in low-income credits simply because for most fixed-income families, sales and property taxes take a much bigger bite out of their wallets than does the personal income tax. Refundable credits on income tax forms are the most cost-effective mechanism for partially offsetting the effects of these other regressive taxes on low-income families. |

Property Tax Circuit Breaker for Homeowners & Renters

States employ a wide variety of mechanisms to reduce the amount of property taxes low- and moderate-income families pay, however they vary significantly in effectiveness. A property tax circuit breaker is the only property tax reduction program explicitly designed to reduce the property taxes on those low-income taxpayers hit hardest by the tax. Its name reflects its design: circuit breakers protect low-income residents from a property tax “overload”, just like an electric circuit breaker. When a property tax bill exceeds a certain percentage of a taxpayer’s income, the circuit breaker offsets property taxes in excess of this “overload” level.

States employ a wide variety of mechanisms to reduce the amount of property taxes low- and moderate-income families pay, however they vary significantly in effectiveness. A property tax circuit breaker is the only property tax reduction program explicitly designed to reduce the property taxes on those low-income taxpayers hit hardest by the tax. Its name reflects its design: circuit breakers protect low-income residents from a property tax “overload”, just like an electric circuit breaker. When a property tax bill exceeds a certain percentage of a taxpayer’s income, the circuit breaker offsets property taxes in excess of this “overload” level.

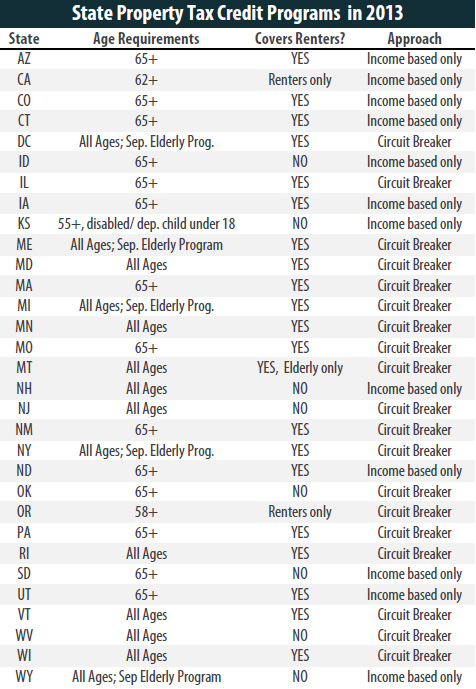

In 2013, 18 states and DC offer true property tax circuit breaker programs which target tax reductions to low-income families who also owe significant property taxes relative to their incomes. Another 12 states provide property tax credits to some low-income families. However, the credits in those states are only based on income—the cut-off eligibilty over income limits but do not include a provision requiring property taxes to exceed a set percentage of income to qualify for the credit.

The most effective and targeted property tax credits are circuit breaker programs made available to all low-income taxpayers, regardless of their age, and are also extended to renters. Because it is generally agreed that renters pay property taxes indirectly in the form of higher rents, many states now extend their circuit breaker credit to renters as well. The calculation is typically the same as for a homeowner, except that renters must assume that their property tax bill is equal to some percentage of their rent paid. Renters in Maryland for instance, use 15 percent of their rent as their assumed property tax in calculating their circuit breaker credit. For a circuit breaker program to be successful an effective outreach campaign is necessary.

2013 State Circuit Breaker Developments

• District of Columbia lawmakers increased income eligibility for the city’s circuit breaker credit from $20,000 to $50,000, increased the maximum credit from $750 to $1,000, increased the share of rent used to calculate property taxes from 15 to 20 percent and indexed the thresholds and credit amounts to inflation.

• Maine lawmakers converted the state’s existing low-income circuit breaker rebate to a new “Property Tax Fairness Credit”, a refundable credit taken via the personal income tax forms. Like the old program, the new credit is available to low- and moderate-income homeowners and renters of all ages. However, the maximum benefit was reduced from $1,600 to $300, income eligibility was lowered, and the acceptable level of property taxes as a share of income was increased. As a result of the changes, more eligible taxpayers are likely to claim the benefit since it no longer requires a separate application process, but fewer overall people will be eligible and the maximum benefit was greatly reduced.

• Minnesota lawmakers increased the benefit of and eligibilty for the state’s property tax refund, a circuit breaker program available to low-income homeowners and renters. A new outreach program will help to ensure that eligibe homeowners and renters receive the benefit.

Recommendation: States interested in reducing property taxes for low-income homeowners and renters should consider introducing a circuit-breaker program. States with circuit breaker programs only available to older adults or homeowners should consider expanding the program to low-income homeowners and renters of all ages.

| WHICH STATES GET IT (CLOSE TO) RIGHT?

The most noticeable features of the least regressive tax states are a highly progressive income tax including targeted tax credits and a lesser reliance on sales and excise taxes. For example: • Vermont’s tax system is among the least regressive in the nation because it has a highly progressive income tax and low sales and excise taxes. Vermont’s tax system is also made less unfair by the size of the state’s refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) — 32 percent of the federal credit— and a generous property tax circuit breaker credit. • Delaware’s income tax is not very progressive, but its high reliance on income taxes and very low use of consumption taxes nevertheless results in a tax system that is only slightly regressive overall. Similarly, Oregon has a high reliance on income taxes and very low use of consumption taxes. Both states also offers a state EITC as well as sizeable credits to offset child and dependent care expenses. • New York and the District of Columbia each achieve a close-to-flat tax system overall through the use of generous refundable EITC’s and an income tax with relatively high top rates and limits on tax breaks for upper-income taxpayers. New York also provides a refundable Child Tax Credit based on the federal program and both states provide property tax circuit breaker credits. It should be noted that even the least regressive states generally fail to meet what most people would consider minimal standards of tax fairness. In each of these states, at least some low- or middle-income groups pay more of their income in state and local taxes than the wealthiest families must pay. |

Targeted Low-Income Tax Credits

Because the Earned Income Tax Credit is targeted to low-income working families with children, it typically offers little or no benefits to older adults and adults without children. Thus, refundable low-income credits are a good complementary policy to state EITCs.

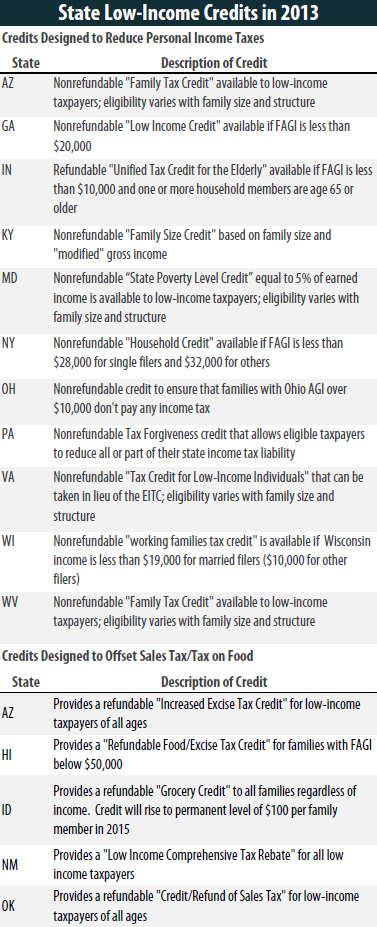

Ten states offer income tax credits of their own design to ensure that families below a certain income level aren’t subject to the personal income tax. For example, Ohio offers a nonrefundable credit which ensures that families with incomes less than $10,000 aren’t subject to the income tax. Kentucky offers a nonrefundable credit based on a family’s size which ensures that families at or below the poverty level aren’t subject to state income taxes. Making these targeted low-income credits refundable would increase their effectiveness for low-income families.

Five states offer an income tax credit to help offset the sales and excise taxes that low- income families pay. Some of the credits are specifically intended to offset some of the impact of sales taxes on groceries. The credits are normally a flat dollar amount for each family member, and are available only to taxpayers with income below a certain threshold. These credits are usually administered on state income tax forms, and are refundable—meaning that the full credit is given even if it exceeds the amount of income tax a claimant owes.

Refundability is important because it allows low-income credits to be used by taxpayers who have little or no income tax liability but who pay a substantial amount of their income in sales taxes. For example, Idaho offers a refundable credit for each Idahoan and their dependents to offset grocery taxes even if taxpayers aren’t subject to the income tax.

There were no significant changes made to state low-income tax credits in 2013. A proposal to enact a nonrefundable tax credit fully eliminating personal income taxes for families living in poverty (and cutting them in half for those between 100 and 125 percent of poverty) failed to pass the Hawaii legislature.

Recommendation: States committed to making sure taxes don’t push families further into poverty should create refundable, targeted low-income credits. Such credits can also be used to make childcare more affordable. In states where these credits already exist, lawmakers should act to enhance them, such as by making them refundable.

Child-Related Tax Credits

Child Tax Credits: The federal income tax law allows taxpayers to claim a $1,000 income tax credit for each dependent child under 17 years of age. The credit amount is gradually phased out for high income families. A portion of the child tax credit is refundable for low-income families.

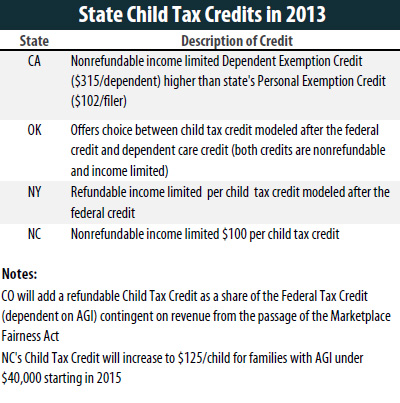

Four states currently offer a much smaller version of the child tax credit for qualifying families (Colorado will join this list contingent on Congress passing a law to allow states to force out-of-state online retailers to collect and remit sales taxes). These per-child credits are an important anti-poverty strategy, especially if they are refundable and income limited. The credits are offered beyond the extra dependent exemptions or exemption credits that most states offer families. For example, New York offers a $100 refundable child tax credit for qualifying families.

Recommendation: States that want to help low-income families with children should consider increasing the value of existing child credits, making them refundable, or introducing a new refundable per child credit.

| STATES PRAISED AS “LOW TAX” ARE OFTEN HIGH TAX STATES FOR FAMILIES LIVING IN POVERTY

Annual state and local data from the Census Bureau is often used to rank states as “low” or “high” tax states based on taxes collected as a share of state personal income. But focusing on a state’s overall tax revenues overlooks the fact that taxpayers experience tax systems very differently. In particular, the poorest 20 percent of taxpayers pay a greater share of their income in state and local taxes than any other income group in all but 10 states (including DC). And, in every state, low- income taxpayers pay more as a share of income than the wealthiest top 1 percent of taxpayers. No income-tax states like Washington, Texas and Florida do, in fact, have average to low taxes overall. But, can they also be considered “low-tax” states for poor families? Far from it. In fact, these states’ disproportionate reliance on sales and excise taxes make their taxes among the highest in the entire nation on low-income families. The bottom line is that many so-called “low-tax” states are high-tax states for the poor, and most do not offer a good deal to middle-income families either. Only the wealthy in such states pay relatively little. |

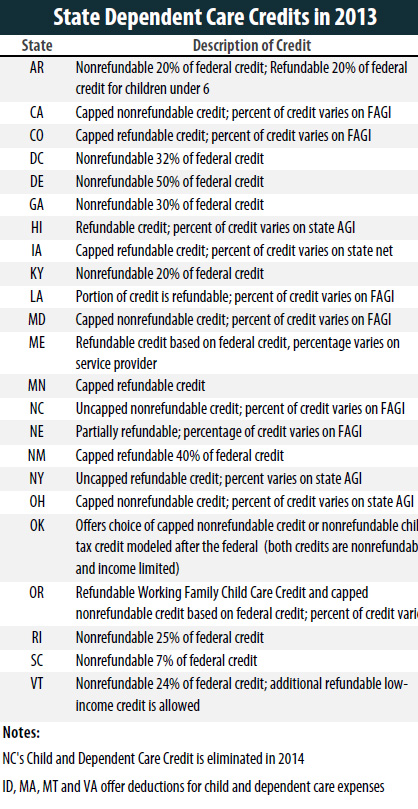

Child and Dependent Care Credits: Low and middle-income working parents frequently spend a significant portion of their income on child care. The federal government allows a nonrefundable income tax credit to help offset child care expenses. In 2012, single working parents (and two-earner married couples) with children under 12 can claim a credit to partially offset up to $6,000 of child care expenses; low-income taxpayers can receive a credit of up to 35 percent of these expenses. The credit percentage gradually falls for higher-income taxpayers. This “sliding scale” approach helps to target tax relief somewhat more effectively to low-income taxpayers, but making the credit refundable would help those parents and children most in need.

Child and Dependent Care Credits: Low and middle-income working parents frequently spend a significant portion of their income on child care. The federal government allows a nonrefundable income tax credit to help offset child care expenses. In 2012, single working parents (and two-earner married couples) with children under 12 can claim a credit to partially offset up to $6,000 of child care expenses; low-income taxpayers can receive a credit of up to 35 percent of these expenses. The credit percentage gradually falls for higher-income taxpayers. This “sliding scale” approach helps to target tax relief somewhat more effectively to low-income taxpayers, but making the credit refundable would help those parents and children most in need.

The majority of the 23 states (including DC) that offer a credit for child and dependent care model their state credit after the federal credit. For example, Georgia allows taxpayers to take 30 percent of their federal child and dependent care credit as their Georgia nonrefundable child care credit. Nebraska takes a slightly different approach that offers both a refundable and a nonrefundable credit depending on a family’s income. The Nebraska refundable child care credit is calculated as 100 percent of the federal credit for low income filers. Higher earners can claim a nonrefundable credit equal to 25 percent of the federal credit. This approach targets the benefits of the Nebraska credit much more efficiently to low- and middle-income parents than does the federal credit. Policymakers should note that these credits do nothing to support families without children or seniors who live in poverty.

2013 State Child Tax Credit Developments

• Colorado lawmakers enacted a new Child Tax Credit for children under age 6. The credit is a sliding percentage of the federal child tax credit with the benefit decreasing as income increases. The credit is contingent on Congress passing a law to allow states to force out-of-state online retailers to collect and remit sales taxes.

• North Carolina lawmakers eliminated the state’s child and dependent care credit as part of a tax overhaul package. Starting in 2015, the state’s child tax credit will increase from $100 to $125 per child for families with adjusted gross incomes under $40,000 (married) or $32,000 (head of household).

Recommendation: States interested in targeting child and dependent care credits to help families most in need would do well to make their credits refundable and make the credit available only to families with limited incomes.

IMPLEMENTATION: A VITAL STEP

Offering the tax policies described in this report is one step to helping lift families out of poverty, but simply offering these credits is not enough. In order to ensure that as many eligible families benefit from these anti-poverty policies as possible, lawmakers should consider how they can make the credits accessible. A simple design, such as linking a credit to an already established credit (as the case with state EITCs) is a good place to start. Allowing taxpayers to claim credits on their personal income tax forms (as opposed to filling out a separate form or application at a different time of the year) makes it more likely that eligible taxpayers will receive the benefits due to them.

Policymakers, advocacy groups, and the media must also work together to ensure an effective outreach program is established and adquately funded so that taxpayers are informed about and can thus receive these credits. An outreach program must also be frequently evaluated to understand the effectiveness of the tax credit offered.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

• States with EITCs should consider increasing the percentage of the existing credit and other states should consider introducing a generous and refundable EITC.

• States should consider introducing a circuit-breaker credit. States with circuit breakers only available to older adults or homeowners should consider expanding the credit to include non-elderly low-income homeowners and renters.

• States should create refundable, targeted low-income credits. Such credits can also be used to mitigate the regressive nature of state sales taxes. In states where these credits already exist, lawmakers should act to enhance them, such as by making them refundable.

• States should consider increasing the value of existing child credits, making them refundable, or introducing a new refundable per child credit.

CONCLUSION

American families living in poverty are in crisis, and state tax systems across the country do too little to offer the assistance low-income families need. Instead, regressive state tax structures are actually pushing families deeper into poverty. State lawmakers have a responsibility to ensure that their state’s tax structures do not exacerbate this crisis.

State lawmakers should consider using the low-income tax credits outlined in this paper as a means of boosting the incomes of low-income families, and should ensure that effective outreach programs are in place to encourage use of the credits already in place in each state. Refundable tax credits are effective and time-tested anti-poverty solutions that would also provide additional income to help families pay for food, housing, transportation and other necessities. The reforms discussed in this paper are among the most cost effective anti-poverty strategies available to lawmakers.

See the PDF version for the State-by-state tables describing current anti-poverty tax policies offered and policies to consider enacting follow.