An updated version of this brief for 2019 is available here.

State lawmakers seeking to make residential property taxes more affordable have two broad options: across-the-board tax cuts for taxpayers at all income levels, such as a homestead exemption or a tax cap, and targeted tax breaks that are given only to particular groups of low- and middle-income taxpayers. One such targeted program to reduce property taxes is called a “circuit breaker” because it protects taxpayers from a property tax “overload” just like an electric circuit breaker: when a property tax bill exceeds a certain percentage of a taxpayer’s income, the circuit breaker reduces property taxes in excess of this “overload” level. This policy brief surveys the advantages and disadvantages of the circuit breaker approach to reducing property taxes.

The Problem: Property Taxes Are Regressive

Residential property taxes are regressive, requiring low-income taxpayers to pay more of their income in tax than wealthier taxpayers. A 2015 ITEP analysis found that nationwide, the poorest twenty percent of Americans paid 3.6 percent of their income in property taxes, compared to 2.6 percent of income for middle-income taxpayers and 0.7 percent of income for the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans. The main reason property taxes are regressive is that home values are much higher as a share of income for low-income families than for the wealthy. Because property taxes are based on home values rather than income, property taxes are disconnected from “ability to pay” considerations in a way that income taxes are not: a taxpayer who suddenly becomes unemployed will find that her property tax bill is unchanged, even though her ability to pay it is greatly reduced.

How Circuit Breaker Credits Work

The basic idea behind the “circuit breaker” approach to reducing property taxes is quite simple: taxpayers earning below a certain income level should be given some amount of property tax relief when their property taxes exceed a certain percentage of their income. But states that have implemented this basic idea have made a range of choices about who should receive the credit and how the credit should be calculated.

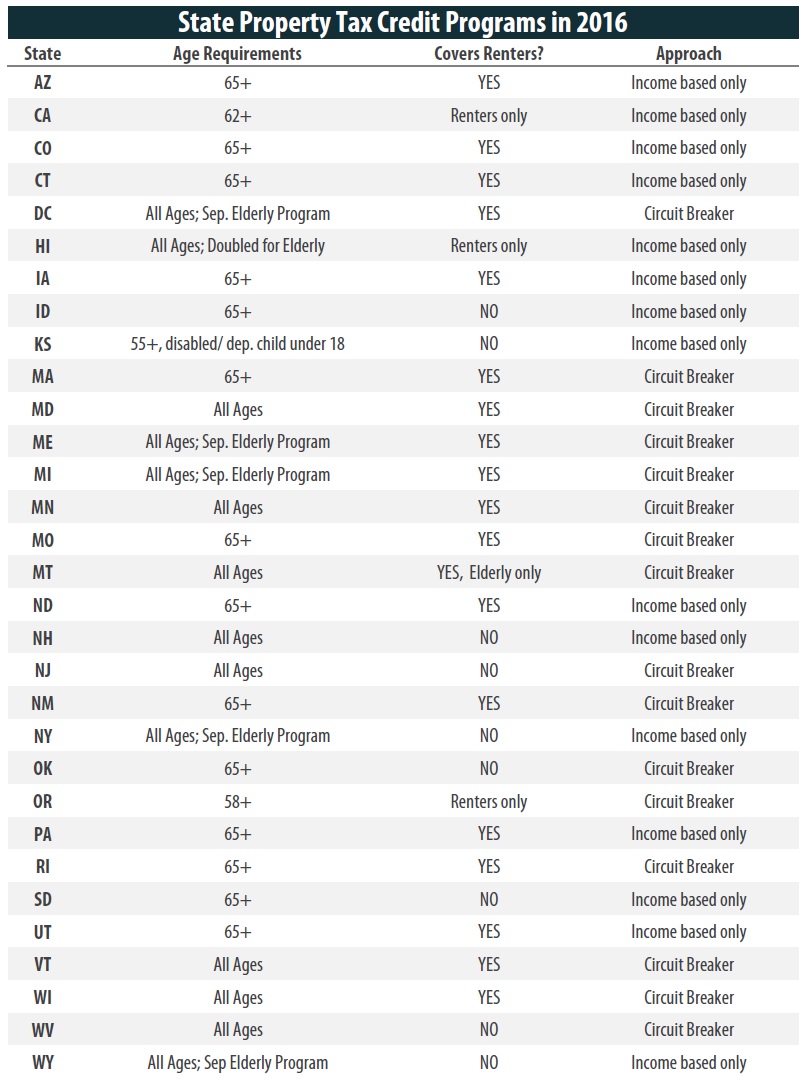

In 2016, fifteen states and DC offered property tax circuit breaker programs. These circuit breakers provide a sophisticated formula to target reductions for those most in need, low-income families who owe significant property taxes relative to their incomes. Another 15 states provide property tax credits to some low-income families based on their income. With eligibility established based solely on income, these credits do not include a provision requiring property taxes to exceed a set percentage of income to qualify for the credit. As a result, those most in need may not be fully protected from a property tax “overload.”

A circuit breaker vs. income-based only approach is just one of many decisions state policy makers must consider when implementing a circuit breaker. There are a series of basic choices to make in designing a property tax circuit breaker program:

Should the credit be available to elderly, non-elderly taxpayers, or both?

Most state circuit breakers target property tax cuts to the elderly, usually based on the perception that elderly taxpayers have less ability to pay taxes due to fixed incomes. Yet non-elderly taxpayers are susceptible to the same property tax “overload” as elderly taxpayers. As a result, many states now extend circuit-breaker benefits to their under-65 population.

Should the credit be limited to homeowners, or extended to renters as well?

It is generally accepted that owners of rental real estate pass through some of their property tax liability to renters in the form of higher rents. For this reason, a growing number of states now extend circuit breaker eligibility to renters. For example, renters in Maryland calculated 15 percent of their rent as assumed property tax in computing their 2015 circuit breaker credit. But many states still provide no property tax reductions to low-income renters.

What should be the maximum income level for eligibility?

In 2015, income limits on state circuit breakers ranged from $5,500 in Arizona to $108,000 in Minnesota. Because higher income eligibility means a costlier credit, many states extend eligibility only to the very poorest homeowners, despite the fact that fast-growing property taxes can be burdensome for middle-income taxpayers too.

What cap should be imposed on the credit?

Every state limits the dollar amount that can be claimed. These limits range from $75 in New York to $8,000 in Vermont.

Should the maximum income level, or the maximum credit, be indexed for inflation?

Failing to tie the value of the credit to inflationary growth will reduce the real value of the credit each year. Indexing income limits (and the maximum credit amount) for inflation helps to ensure that circuit breakers continue to provide meaningful low-income tax relief in the long run. Many states have unintentionally allowed the value of their circuit breakers to decline over time by ignoring the impact of inflation. (See ITEP Brief, “Indexing Income Taxes for Inflation: Why It Matters” for more information).

What percentage of income should be considered an “overloaded” property tax bill?

Some credits have no threshold: all low-income taxpayers are deemed worthy of a tax cut. Others require taxes to exceed a threshold. For example, West Virginia taxpayers can only claim the credit if their property taxes exceed 4 percent of their income.

How to best administer the credit?

States vary in their administration of circuit breaker credits, ranging from automatic rebates to administration through state property tax or income tax systems. The option to claim these credits through the personal income tax will greatly expand its reach. However, taxpayers who do not file income tax returns should be able to claim the credit via a stand-alone rebate.

Advantages of Circuit Breakers

The circuit breaker is the only property tax reduction that is explicitly designed to reduce the property tax load on those low-income taxpayers hit hardest by the tax. Circuit breakers offer several advantages over more general property tax cut measures:

Circuit breakers are targeted to selected income groups.

As a result, they are much less expensive than “across the board” property tax breaks like homestead exemptions or tax caps, and the benefits go only to the taxpayers for whom property taxes represent a disproportionate amount of income.

Because circuit breaker credit amounts vary with income, the use of these credits introduces an “ability to pay” criterion that the property tax lacks.

Circuit breakers help offset the unfairness of a regressive property tax by identifying the individual taxpayers for whom property taxes are most burdensome and reducing their tax to a manageable level.

Low- and moderate-income taxpayers who typically benefit from circuit breakers do not itemize their federal income taxes, so this form of reducing property taxes is usually not offset by increases in federal income taxes.

By contrast, property tax cuts for wealthier taxpayers will result in a federal income tax hike, since these cuts will reduce the amount of state tax that wealthy taxpayers can write off on their federal tax forms. (See ITEP Brief, “How State Tax Changes Affect Your Federal Taxes: A Primer on the Federal Offset” for more information).

Disadvantages of Circuit Breakers

The main drawback of circuit breakers is that, in general, they are only given to taxpayers who apply for them (by contrast, general “homestead exemptions” are given automatically in the form of reduced property tax bills). Eligible taxpayers will only apply for circuit breaker credits if they are aware of their existence. This means that an essential component of a circuit breaker program must be an educational outreach effort designed to inform state taxpayers of the credit. In addition, one way of making it easier for eligible taxpayers to claim the circuit breaker is to offer the option of claiming the credit either on income tax forms or on a separate circuit breaker form for those who do not have to file income taxes.

Conclusion

Circuit breakers are an attractive approach to reduce the property tax because they are better targeted and less costly than “across the board” tax relief mechanisms such as tax caps and homestead exemptions. These credits are a valuable tool for lawmakers seeking to lessen the property tax load on their most vulnerable residents, without depleting the state budget.