State lawmakers frequently make claims about how proposed tax changes would affect taxpayers at different income levels. Yet too many lawmakers routinely ignore one important consequence of their tax reform proposals: the effect of state tax changes on their constituents’ federal income tax bills. Wealthier taxpayers in particular can use federal income tax rules to partially offset their state and local taxes. This “federal offset” has important implications for how state tax changes affect taxpayers in practice.

The “Federal Offset”: How It Works

Federal income tax rules allow taxpayers to claim itemized deductions for certain expenses that affect their ability to pay taxes. For example, you can use these deductions to offset part of the cost of charitable contributions, home mortgage interest payments, and extraordinary medical expenses. Additionally, many state and local tax payments (including property taxes and your choice of either sales or income taxes) are also deductible. As a result, if you itemize on your federal return, some of the state taxes you pay are ultimately offset by a reduction in your federal taxes. Put another way, the federal government effectively pays a portion of your state and local tax bill. This feature of the federal income tax is sometimes called the “federal offset.”

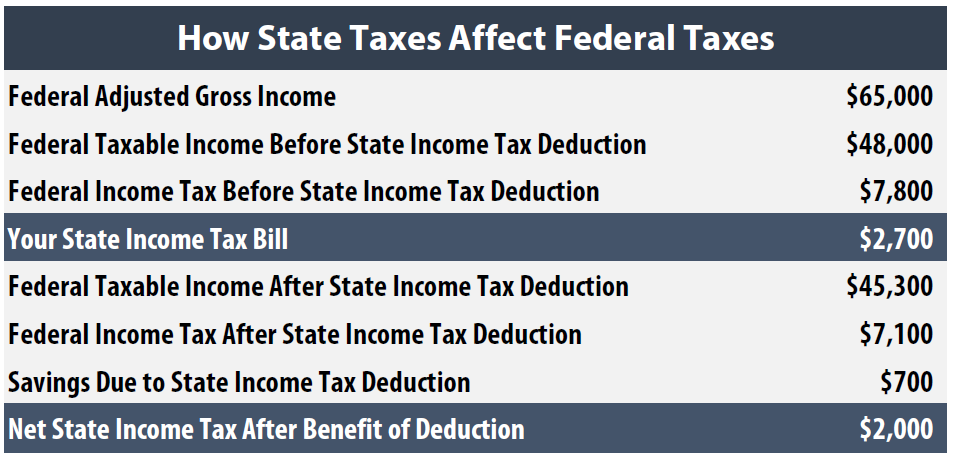

The chart on this page helps to explain how this works. Suppose you are a single person living in Georgia earning $65,000 per year. After claiming most deductions, your taxable income might be about $48,000, which means your federal income tax bill would amount to $7,800 and your Georgia income tax would be roughly $2,700.

But this isn’t the whole story. Since you can write off your state income taxes as an itemized deduction, your actual taxable income will be reduced to $45,300 (instead of $48,000) after subtracting your $2,700 state income tax bill. As a result, your federal income tax bill drops to about $7,100—a savings of about $700. In other words, 25 percent (or $700) of your state income tax bill is ultimately paid by the federal government. At the end of the day, what comes out of your pocket due to the state income tax is only $2,000—not $2,700, as it might have originally seemed. Taxpayers can also deduct their state and local property taxes and can choose to deduct sales taxes instead of income taxes if they prefer, and this example works in much the same way for those taxes.

Who Benefits?

The practical impact of being able to write off these state and local taxes is that if you itemize on your federal return, your state and local tax bills are never as large as they appear. The size of the federal tax cut you receive, however, can vary significantly.

Lower-income taxpayers, for example, typically do not itemize and are therefore often barred from taking advantage of the federal offset. Even among those taxpayers that do itemize, the benefit of any given deduction tends to be larger for higher income families.

For example, a moderate income taxpayer in the 10 percent federal tax bracket will see a federal tax reduction equal to, at most, 10 percent of the state and local taxes she deducts. But wealthier taxpayers who pay at the top marginal rate of 39.6 percent can see savings as large as 39.6 percent of their deduction. Tax deductions, including those for state and local taxes, are often regressive because being able to shield a dollar from tax is more valuable to wealthier taxpayers who would see that dollar taxed at a higher rate in the absence of such a deduction.

Evaluating State Tax Proposals: Federal Interaction Matters

The federal offset has clear implications for proposals to increase (or cut) state taxes. For example, when state income taxes go up, part of that tax hike will not come out of state residents’ wallets at all, but instead will be paid by the federal government in the form of federal tax cuts for itemizers. State income tax cuts have a similar offsetting effect: when state income taxes go down, so does the amount of state income tax that can be written off by itemizers on federal tax forms—and federal income taxes go up as a direct result.

Just how much of a state tax hike will be paid by the federal government depends on two factors: the degree of progressivity of the state tax hike, and which type of tax is being increased. Since wealthy taxpayers are most likely to itemize, and pay at higher federal income tax rates, the most effective way to export a state tax hike to the federal government is to focus the tax hike on wealthier taxpayers. Property and sales taxes generally take only a small part of the wealthiest taxpayers’ income, so the federal offset from a property or sales tax change will be fairly small. In addition to being regressive, excise taxes on items such as cigarettes or alcohol are not deductible at all, meaning they offer no federal offset benefit. But state income taxes are both deductible and progressive, meaning that they require wealthier taxpayers to pay more of their income in tax. As a result, income tax changes have the potential to produce the largest offset effects—and the more the state income tax change targets the wealthiest taxpayers, the larger the associated offset effect.

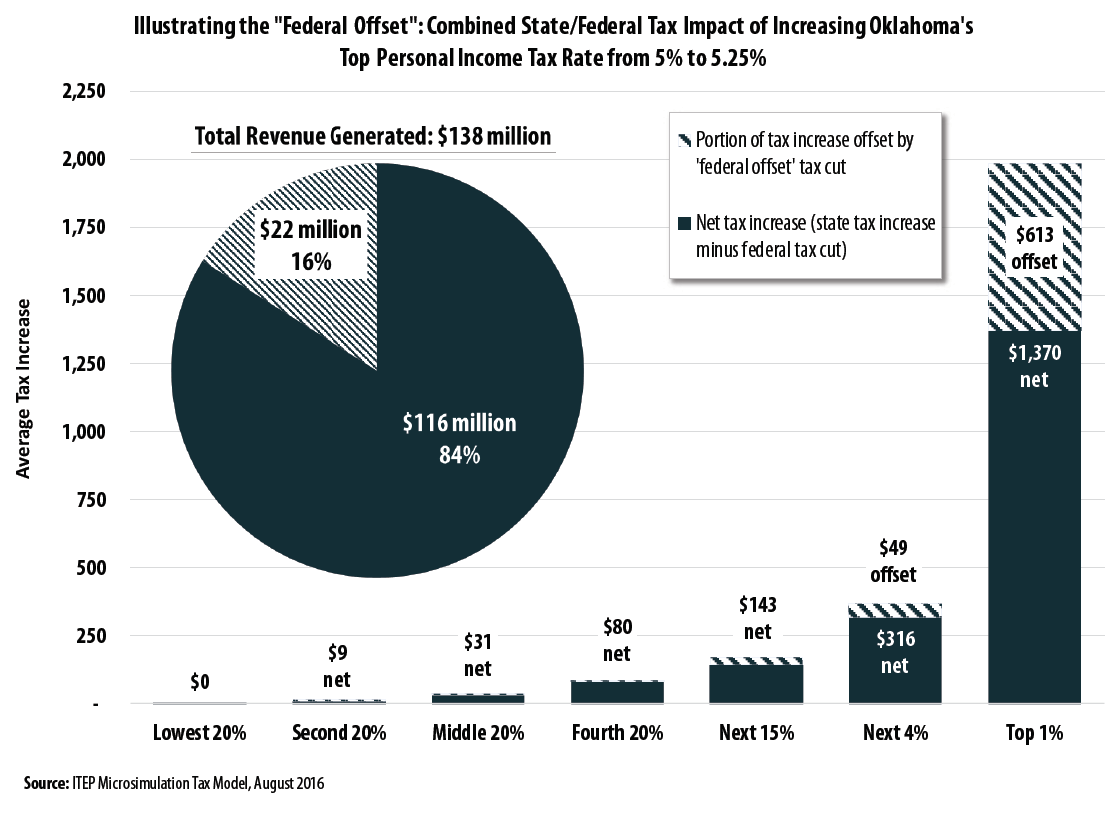

The nearby graph helps illustrate this point by examining a hypothetical increase to Oklahoma’s top personal income tax rate. Throughout most of the income distribution, the federal offset effect (depicted by the striped segments) cancels out between 5 and 15 percent of the state tax increase. The story is dramatically different for high-income taxpayers, however, who see over 30 percent of their state tax increase offset by a cut in their federal tax bills—bringing their average net impact down from almost $2,000 per taxpayer to just $1,370.

From the perspective of individual taxpayers, the federal offset makes most state income tax increases a good deal and most state income tax cuts a lousy deal. State lawmakers face the same basic math, even if they don’t always recognize it. For a state looking to raise revenue, maximizing the federal offset can be a smart approach, as in the Oklahoma example above that would generate $138 million in revenue while only raising Oklahomans’ tax bills by $116 million. And for states considering tax cuts, the federal offset gives lawmakers a chance to decide whether the tax cuts ought to go to state residents or to the federal government. When lawmakers enact income tax cuts targeted to wealthy taxpayers, they’re essentially choosing to send up to 39.6 percent of the tax cut to Washington, D.C. But when lawmakers enact targeted low-income tax cuts, they’re targeting all or nearly all of their tax reductions to state residents.

Federal Deductibility—A Neglected, but Important Tool

Lawmakers who cut state income taxes should recognize that much of the revenue they forgo will ultimately flow to the federal government’s coffers rather than to their constituents. Conversely, raising revenue through progressive income taxes, in addition to lessening state tax regressivity, has the added benefit of exporting much of the cost to the federal government. This is not the case with sales and excise taxes, which primarily impact low- and middle-income taxpayers and are accompanied by little or no federal offset effect. The federal offset has important implications for the final impact of various types of state and local tax changes. Greater awareness of the federal offset can help state policymakers design better targeted tax policies.