In the summer of 2016, House Republicans released a blueprint for tax reform that is likely to be used as the starting point for major tax legislation in 2017.[1] One of the most radical provisions is a proposal to shift the corporate tax code from a residence-based to a destination-based system through applying a border adjustment on exports and imports. This proposal has major flaws that would make it a challenge to implement. Further, it is inherently regressive, rife with loopholes and would violate international agreements.

How the Destination-Based System Proposal Works

The GOP tax proposal would achieve a destination-based tax system by applying a border adjustment, similar to those typically applied to value-added taxes (VAT), to the U.S. corporate income tax. While its implications are complex and would represent a fundamental shift in our tax code, the mechanism for this change is relatively simple. When a company exports a product out of the United States, the revenue earned from that product would be exempt from the U.S. corporate income tax. Inversely, companies that import products would no longer be able to deduct product costs as an expense.

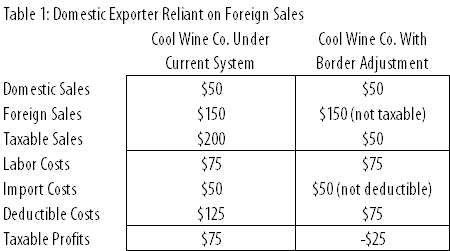

To illustrate how this would work, consider a simplified example of how the current worldwide system (ignoring the foreign tax credit and deferral) and the border adjustment system would apply to a U.S. wine company with a substantial amount of foreign sales in Table 1 below.

Under the current system, taxable profits are calculated by adding the foreign and domestic sales ($200) and then subtracting the total labor and import costs ($125) to get a taxable income of $75. In contrast, under the border adjustment system, foreign sales and import costs are ignored, so the calculation is domestic sales ($50) minus labor costs ($75) to get a taxable income of negative $25. In Table 1, Cool Wine Co. ends up having a smaller amount of taxable profits because the inability to deduct the cost of its imports ($50) is outweighed by the benefit it receives from escaping taxation on its foreign sales ($150).

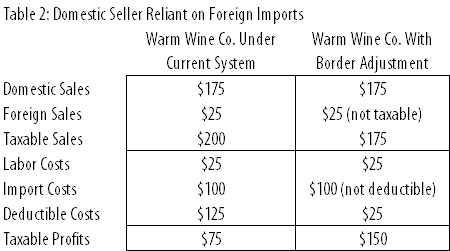

The opposite effect is possible for a company that relies more heavily on imports and domestic sales. As Table 2 illustrates, if Warm Wine Co. relied $50 less on labor, $50 more on imports and sold $75 more of its products domestically, its taxable profits would not change ($75) compared to Cool Wine Co. under the current system. In contrast, with the border adjustment, its taxable profits would double to $150 because these profits would be a function of their domestic sales ($175) minus their labor costs ($25).

Using a real-world example, reporting on Constellation Brands, the U.S. distributer of Corona, has revealed that the company would likely be negatively affected by the tax because of the high volume of its Mexican products that are imported into the United States. The company has noted how it could potentially shift some of its costs to the United States to mitigate the effects of the border adjustment tax, but this would force significant changes to its supply chains.[2]

Before digging deeper into the myriad challenges the border adjustment tax would raise, it is critical to note several other major changes that the House Republican’s plan would make to the corporate tax code. First, the plan would allow for the immediate deduction of the full cost of capital investment, while at the same time disallowing any deduction for interest expenses. These reforms turn the corporate income tax into a tax on a company’s cash flow. Because of the combination of the border adjustment and the shift toward a cash flow tax, the House GOP proposal has been referred to as a destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT). Because this report focuses primarily on the border adjustment piece, we will refer to the House GOP corporate tax proposal as the border adjustment tax. In addition, the plan would lower the corporate tax rate from 35 to 20 percent and eliminate all major corporate tax breaks except for the research credit. These changes are inextricably linked to the border adjustment in the sense that the border adjustment is intended to pay for the rate cut and the shift to a cash flow tax is supposed to help make the border adjustment on the corporate tax legal for international trade purposes (something it ultimately fails in doing).

It is also important to note that the House Republican plan has not been fully fleshed out into legislative text, so it remains to be seen exactly how the border adjustment tax will work in practice. That said, the broad strokes laid out in the plan and the work by its proponents provide sufficient detail to raise a number of concerns with the border adjustment tax they are advocating.

Three Key Issues with the Border Adjustment Tax

1. The Proposed Border Adjustment Would Be Regressive

For purposes of trade agreements, proponents of the border adjustment tax claim that it is effectively a VAT or a consumption tax. Consumers pay VATs, but when it comes to the question of who ultimately pays the border adjustment tax, its proponents claim it is still a highly progressive corporate income tax, rather than a much more regressive consumption tax. The reality is that the border adjustment tax is not quite a corporate income tax or a VAT, but either way it is shifting more of the corporate tax onto consumers, making it inherently more regressive than the existing corporate income tax.

Passing some portion of the border adjustment tax on to consumers in the form of price increases is the border adjustment tax’s core fairness problem. The reason consumers would likely see price increases is that U.S. companies would receive a tax subsidy in comparison to imported products since domestic producers will be allowed to deduct wages and salaries from their taxable income earned from the sale of a product, whereas foreign sellers will not. This means that companies producing goods overseas would face a significant tax increase, which would rise or fall depending on the labor intensity of the product in question with more labor intensity bestowing a bigger tax disadvantage to importers. To compensate for its net loss in after-tax profits, a company dependent on imports would (to the extent the market allows) increase the price of its products.

Proponents of the border adjustment argue that to the extent that there is an export subsidy or import penalty, they will be reversed entirely by the change in the exchange rate as a result of the border adjustment tax.[3] While it is very likely that the border adjustment tax would cause a significant appreciation in the dollar, there are a number of reasons to be extremely skeptical of the argument that it will perfectly offset any distortions. To start, theoretical currency models have been shown repeatedly to be disconnected from the actual fluctuations in the market, which likely reflects that highly speculative nature of the market.[4] According to HSBC, only a small amount, 1.4 percent, of daily currency turnover in the U.S. dollar market is based on trade.[5] So the exchange rate is likely to fluctuate due to factors completely independent from the border adjustment tax. Adding to this, the only empirical look at the effects of the border adjustments found that, contrary to economic theory, border adjustments do have a distortive effect on trade.[6] This finding is especially telling since the analysis looked at the border adjustment of VATs, which should theoretically have less of a distortive effect than the border adjustment tax.

Another problem with the currency adjustment point is that there is reason to believe that such an adjustment could take years to offset the impact of the border adjustment tax. In fact, one study from economists projected that the currency could take five years to appreciate to the desired level. This means that in the meantime, import dependent industries could face enormous hits to their after-tax earnings.[7]

Even if the border adjustment tax causes the immediate 25 percent appreciation that its proponents postulate, this would not fully correct the distortion that would be created by the border adjustment tax. The problem is the change in the currency appreciation would apply across the board and thus would only mitigate the average export subsidy and import penalty. This means that domestic producers or importers dealing with products that have a higher than average labor intensity would see the tax distortion only partially corrected by the appreciation in the dollar.[8]

Given the untested nature of the border adjustment tax, it is difficult to forecast the exact impact it will ultimately have on prices. What is clear is that some amount of the tax will almost certainly be passed on to consumers by companies seeking to offset potentially enormous tax hikes on imported products. Economists across many industries have put out reports estimating the huge impact it will have on prices and in import dependent industries. For example, economists have estimated that the border adjustment tax could increase gas prices by 30 cents per gallon.[9] Similarly, financial analysts estimate that the border adjustment tax could raise apparel prices by 15 percent. Another analysis found the six big retailers alone could end up facing a $13 billion hit to annual earnings from the tax.[10] An analysis from Ernst and Young found the item potentially most affected would be motor vehicles.[11]

Overall, one analysis of the plan found that even assuming a significant appreciation in the dollar, the border adjustment tax would have hugely regressive effects. It found that the bottom 10 percent of taxpayers may see their taxes go up by 5 percent of their pretax income, while the top 10 percent of taxpayers would only see their taxes go up by about 1.5 percent of their pretax income.[12] What all this means is that the border adjustment would effectively turn the normally progressive corporate income tax, in part at least, into a regressive tax on consumption.

Taking a step back, it is critical to acknowledge that whatever appreciation the dollar experiences due to the border adjustment tax is no free lunch and will have huge downsides. A substantial appreciation of the dollar would represent a massive transfer of wealth from U.S. investors with foreign holdings to foreign investors with U.S. holdings. One estimate, an appreciation of the dollar due to a border adjustment would result in trillions in losses for American investors and trillions in benefits to foreign investors.[13] Another group of economists estimated that a rise in value of the dollar of 20 percent would equal a capital loss to the U.S. of 13 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).[14]

Further appreciation of the dollar would also add to the pain of developing countries already being hammered by the recent increase in the value of the dollar.[15] Many developing countries maintain substantial debts denominated in dollars, so a 25 percent appreciation in the dollar could functionally increase their debt burdens by an additional 25 percent. A sudden and significant appreciation in the dollar could, as The Economist put it, “threaten the health of the world economy.”[16]

Finally, it’s important to note that the House GOP plan would use all of the estimated $1.2 trillion in revenue that the border adjustment raises (which generously assumes that the border adjustment overcomes its legal hurdles and does not spark trade disputes) to help pay for cuts to the corporate tax rate.[17] Even with this substantial boost in revenue, it’s worth noting that the House GOP plan as written now would still represent a net cut in corporate taxes, one of the most progressive sources in the tax code, by about $1.3 trillion over the next decade.[18] In other words, any revenue raised from corporations through the border adjustment would be more than offset by cuts to the corporate tax rate overall.

2. The Proposed Border Adjustment Would Not End Offshore Tax Avoidance

The allure of the border adjustment tax for some of its proponents is based on the belief that moving to a destination-based corporate tax system is the best way to crack down on tax avoidance. The problem is that this belief is largely untested. In fact, there is every reason to believe that while many of the current methods of tax avoidance will be curbed, companies will find numerous new opportunities to avoid taxes and this new system will create new distortions in the tax code.

The fundamental idea behind the claim that the border adjustment tax would end tax avoidance by focusing taxation on the location of sales is that shifting income to tax havens will no longer matter to companies and thus reduce their ability to avoid taxes. The problem is that just as companies can shift profits to avoid the current corporate tax, they would be able to avoid a border adjustment tax by shifting sales.[19]

Even before the multi-billion-dollar tax avoidance industry begins lobbying in earnest, academics have already outlined in broad strokes some of the tax avoidance opportunities that the border adjustment tax would create. To start, multinational corporations could begin making more of their sales directly to consumers from foreign countries. For example, Microsoft could sell its Windows software at an artificially high price to a subsidiary in Ireland (or any other tax haven), which could then sell it directly to a U.S. consumer nearly tax free. Even if the border adjustment tax included a rule blocking companies from doing this sort of shifting internally, companies could split into separate entities to facilitate this sort of tax avoidance.[20]

A second substantial area of tax avoidance concern is that the border adjustment tax may simply follow the lead of the VAT and exempt financial transactions entirely from the tax base. In addition to providing companies with a tax-free stream of income, taking this approach would be a bonanza for financial companies, which would see their profits become entirely exempt from tax. The most likely alternative to this approach would be to keep the current treatment of financial transactions, which would mean carrying over a substantial avenue of tax avoidance from our current system.[21]

Another significant distortion and tax avoidance opportunity that the border adjustment tax could create is the incentive for companies with substantial exports to merge with companies that depend on a substantial amount of imports.[22] The basic reason for this is that the border adjustment tax is unlikely to allow exporting companies to receive a tax credit back for their paper losses due to the exclusion of foreign sales (see Table 1 above) from their taxable profits. Rather than allowing a company to receive a full tax credit on their losses, companies would simply receive net operating losses which they could carry forward indefinitely. This distortion is created because export heavy companies that continuously report losses in the U.S. would not be able to see any benefit from those net operating losses unless they have profit to offset. Given that importing companies would be facing the opposite problem—specifically, artificially high taxable profits—this creates a huge incentive for heavy importers to combine with heavy exporters to take advantage of the unused tax breaks from net operating losses of the exporting company. Put more concretely, this new tax system would create a bizarre and distortive tax incentive for companies with little in common such as Target (an import dependent retailer) to merge with Boeing (an export heavy manufacturer).

Given the untested nature of the destination-based approach to corporate taxation, it is possible that under the border adjustment tax the United States could end up with a tax system that is even more avoidance prone than our current system. While proponents of the border adjustment tax point to the decades of experience enforcing the VAT as showing that a border adjustment has been tested, the border adjustment tax would likely not enjoy many of the administrative advantages of a VAT because it does not use the credit invoice approach used by nearly every country in administering their VAT. If the goal is truly to end tax avoidance, the less risky approach would be to close the loopholes and embrace international coordination to fix our current corporate income tax system.

3. The Proposed Border Adjustment Would Violate Trade Rules and Tax Treaties

Perhaps the most significant problem with the border adjustment plan as proposed in the House GOP plan is that it would likely violate international trade law and U.S. tax treaties with nearly every major trading partner in the world.

The WTO Problem

The World Trade Organization (WTO), of which the United States is a member, seeks to prevent countries from unfairly subsidizing exports or penalizing imports. To this end, the key criteria for the WTO in evaluating a country’s tax system is whether the country treats domestic and foreign products equally. When a border adjustment is applied to a normal VAT it typically passes this test because a consumer in each country is paying the same VAT rate on the price of an imported and domestically produced item.

Proponents of the House GOP plan argue that the WTO should see the border adjustment tax as akin to a VAT and thus would rule the border adjustment permissible. The central problem with this is that the border adjustment tax is distinctly not a VAT because it allows for the deduction of wages and salaries paid out by a domestic producer. This is not a minor difference; wages and salaries constitute a huge portion of the base of the VAT. As experts at Ernst and Young have noted in discussing the border adjustment tax, compensation constitutes about 62 percent of the consumption base in the United States.[23] Given this, the border adjustment tax should be called a VAT, with a deduction for most of the value-added.[24]

The retention of a deduction for wages and income would create precisely the sort of export subsidy that WTO rules are intended to prevent. Domestic production would be favored under the border adjustment tax because the domestic price excludes the cost of labor for tax purposes, but the cost of the tax on labor is not excluded when applied to the purchase of an import. This problem could be solved by either not allowing the deduction for compensation domestically (thus turning the border adjustment tax into a proper VAT) or providing some form of grant to companies based on the wage and income tax cost implicit in the price of the import (a practically and politically difficult thing to do).[25]

The implication of all of this is that the WTO would be very likely to strike down the border adjustment as illegal.[26] Unless the U.S. sought to blow up the international trade regime by ignoring the WTO’s ruling, this would mean that the U.S. would either need to repeal the border adjustment, convert the tax more properly into a VAT or face retaliatory trade barriers. Before a ruling is even made, countries could impose retaliatory tariffs or border adjustments, which could substantially harm the U.S. and world economy. In fact, officials in Mexico[27] and the European Union are already suggesting that they would retaliate if the border adjustment tax goes into effect.[28] Even if the WTO ultimately finds the border adjustment tax admissible, such a ruling would take years to determine and result in a substantial amount of uncertainty and instability as the world waits for the ruling or afterward shifts tax regimes to take advantage of new WTO tax rules created by the ruling. Businesses would be reluctant to make major investment and merger and acquisition decisions for years, which would significantly undermine economic growth.

Tax Treaties

Both the U.S. corporate tax system and U.S. multinational companies benefit from the coordination and stability provided by the tax treaties that the United States has established with more than 65 countries across the world.[29] The implementation of the border adjustment tax would require substantial revisions to these established treaties.

Tax scholars Reuven Avi-Yonah and Kimberley Clausing note three problems that the border adjustment tax would create for tax treaties. First, it would require doing away with permanent establishment as a requirement for taxation, which means taxing firms that did not previously have enough business or physical presence in the United States to be taxed. This may not be a light lift considering that reforms around permanent establishment were rejected by treaty partners as part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) led Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project. A second issue that would require a significant treaty override is new language dealing with the taxation of derivatives and royalties to avoid new opportunities for tax avoidance. Finally, much like the issues mentioned above with the WTO, many U.S. tax treaties have non-discrimination provisions that partner countries could accurately claim are violated by the imposition of the border adjustment tax due to its exemption of wages and salaries discussed above.[30]

For decades, countries across the world have worked with increasing coordination to make the international tax and trade system function more efficiently. The border adjustment tax would blow up the decades of work toward this goal. Even after years of difficult transition and rebuilding, the international system could very well end up in a worst place than it started by abandoning residence-based taxation.

What Effective Corporate Reform Looks Like

The one point that proponents of the border adjustment tax get right is that our current corporate tax code needs significant reform. Rather than embrace a reform approach that is illegal, regressive and loophole-ridden, there are much more straightforward ways to reform our current system. The single best way to shut down corporate tax avoidance would be to end the ability of companies to defer taxes on their foreign profits.[31] This would eliminate the incentive for companies to shift their profits into offshore tax havens and could raise nearly $1 trillion in revenue, an amount on par with the revenue theoretically raised by the border adjustment tax.[32] Complementing this approach, measures to curb earnings stripping and prevent inversions should be enacted in order to ensure that foreign companies or U.S. companies pretending to be foreign don’t have a tax advantage over U.S. companies.[33] Short of ending deferral, there are a host of additional anti-tax haven abuse measures that could be taken to tighten up the current system, including the repeal of the “check-the-box rules” and requiring companies to pool their foreign tax credits.[34] More broadly, the corporate tax code should be wiped clean of distortive tax expenditures, such as accelerated depreciation, the domestic manufacturing credit, and many others.[35]

Ending deferral and the other major tax loopholes in the corporate tax code could raise a tremendous amount of money. In fact, an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that a flat, loophole-free corporate tax could raise $148 billion more each year at the current 35 percent tax rate. Given the substantial amount of revenue raised, the corporate tax rate could even be lowered to 30 percent and still raise $63 billion in additional revenue annually.[36]

Ensuring that corporations pay their fair share is critical to maintaining a progressive and adequate tax system. The border adjustment tax would make our tax system more regressive, while at the same time move our tax system to a more loophole-ridden tax base. Instead of moving to the border adjustment tax, the better approach would to close the loopholes in our current tax system.

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Ryan Tax Plan Reserves Most Tax Cuts for Top 1 percent, Costs $4 Trillion Over 10 Years, “ June 29, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/06/ryan_tax_plan_reserves_most_tax_cuts_for_top_1_percent_costs_4_trillion_over_10_years.php

[2] Vipal Monga and Jennifer Maloney “Constellation Brands Gearing Up for GOP Border Tax,”

Wall Street Journal, January 5, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/constellation-brands-gearing-up-for-gop-border-tax-1483659894

[3] Tax Foundation, “Exchange Rates and the Border Adjustment,” December 15, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/exchange-rates-and-border-adjustment/

[4] Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Kimberly A. Clausing “Problems with Destination-Based Corporate Taxes and the Ryan Blueprint,” U of Michigan Law & Econ Research Paper No. 16-029. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2884903

[5] Chelsey Dulaney, “Border Tax Could Upend Global Markets, but Investors Shy Away From Any Bets,” Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/border-tax-could-upend-global-markets-but-investors-shy-away-from-any-bets-1486900841

[6] James Hines, Jr. and Mihir A. Desai, “Value-Added Taxes and International Trades: The Evidence,” November 17, 2005. https://www.law.umich.edu/centersandprograms/lawandeconomics/workshops/Documents/Fall2005/hines.pdf

[7] Interindustry Forecasting at the University of Maryland (Inforum), “Macroeconomic Impact Analysis of the Business Provisions of the House GOP Blueprint for Tax Reform” January 10, 2017. http://www.inforum.umd.edu/papers/otherstudies/2017/blueprint_impact_analysis_011017.pdf

[8] Wei Cui, “Destination-Based Cash-Flow Taxation: A Critical Appraisal,” University of Toronto Law Journal, January 3, 2017. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2887218

[9]The Brattle Group, “Border Adjustment Import Taxation: Impact on the U.S. Crude Oil and Petroleum Product Markets,” December 16, 2016. http://www.brattle.com/system/publications/pdfs/000/005/384/original/FINAL_Border_Tax_Paper_2016_12_16.pdf?1481912863

[10] Susan Pulliam, Sarah Nassauer and Richard Rubin, “Retailers Risk Multibillion-Dollar Earnings Hit Under GOP Tax Plan,” Wall Street Journal, January 6, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/retailers-risk-multibillion-dollar-earnings-hit-under-gop-tax-plan-1483698602

[11] Barney Jopson, “Corporate America split over radical Republican import tax plan,” Financial Times, January 26, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/cf3f1d98-e356-11e6-8405-9e5580d6e5fb

[12] Kadee Russ, “Distributional Implications of the Border Adjustment Tax for U.S. Households: Lower- and middle-income households may be hard hit,” Econbrowser, January 29, 2017. http://econbrowser.com/archives/2017/01/guest-contribution-distributional-implications-of-the-border-adjustment-tax-for-u-s-households-lower-and-middle-income-households-may-be-hard-hit

[13] Edward D. Kleinbard, “The Right Tax at the Right Time,” USC Law Legal Studies Paper No. 16-36, December 1, 2016. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2878949

[14] Emmanuel Farhi, Gita Gopinath and Oleg Itskhoki, “Trump’s Tax Plan and the Dollar,” Project Syndicate, January 3, 2017. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/trump-tax-plan-hurts-competitiveness-by-emmanuel-farhi-et-al-2017-01

[15] Patrick Gillespie, “Biggest loser from the strong dollar: Emerging Markets,” CNN Money, March 31, 2015. http://money.cnn.com/2015/03/31/investing/us-dollar-strong-emerging-markets/

[16] The Economist, “Republican plans to cut corporate taxes may have unpleasant side-effects,” December 17, 2016. http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21711885-paul-ryans-tax-overhaul-would-send-dollar-soaring-republican-plans-cut

[17] Tax Policy Center, “An Analysis of the House GOP Plan,” September 16, 2016.

[18] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Ryan Tax Plan Reserves Most Tax Cuts for Top 1 percent, Costs $4 Trillion Over 10 Years, “ June 29, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/06/ryan_tax_plan_reserves_most_tax_cuts_for_top_1_percent_costs_4_trillion_over_10_years.php

[19] Martin A. Sullivan, “Economic Analysis: Difficulties With the House GOP’s Business Cash Flow Tax,” Tax Notes, August 8, 2016. http://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes/tax-policy/economic-analysis-difficulties-house-gops-business-cash-flow-tax/2016/08/08/18562811

[20] Daniel Hemel, “A Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax in a Digital Age (or, How To Game the House Republicans’ Plan),” December 20, 2016. https://medium.com/whatever-source-derived/a-destination-based-cash-flow-tax-in-a-digital-age-or-how-to-game-the-house-republicans-plan-84f82234d76c

[21] David P. Hariton, “Financial Transactions and the Border-Adjusted Cash Flow Tax,” Tax Analysts, January 11, 2017. http://www.taxanalysts.org/content/financial-transactions-and-border-adjusted-cash-flow-tax

[22] RSM, “Border Adjusted Tax proposals may impact exporters and importers,” January 17, 2017. http://rsmus.com/what-we-do/services/tax/international-tax-planning/border-adjustment-proposals-may-significantly-benefit-export-act.html

[23] Ernst & Young, “US tax reform: a border adjusted cash flow tax?,” EY Tax webcast, January 5, 2017. http://www.ey.com/gl/en/issues/webcast_2017-01-05-1800_consumption-based-tax

[24] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Ryan Tax Plan Reserves Most Tax Cuts for Top 1 percent, Costs $4 Trillion Over 10 Years,” June 29, 2016. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2016/06/ryan_tax_plan_reserves_most_tax_cuts_for_top_1_percent_costs_4_trillion_over_10_years.php

[25] Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Zhiyao (Lucy) Lu, “Border Tax Adjustments: Assessing Risks and Rewards,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 2017. https://piie.com/system/files/documents/pb17-3.pdf

[26] Wei Cui, “Destination-Based Cash-Flow Taxation: A Critical Appraisal,” University of Toronto Law Journal, January 3, 2017. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2887218

[27] Michael O’Boyle, “Mexico set to ‘mirror’ policy on any U.S. trade tax change: minister,” Reuters, January 23, 2017. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-mexico-idUSKBN157213

[28] Shawn Donnan, Barney Jopson and Paul McClean, “EU and others gear up for WTO challenge to US border tax,” Financial Times, February 13, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/cdaa0b76-f20d-11e6-8758-6876151821a6

[29] Internal Revenue Serice (IRS), “United States Income Tax Treaties – A to Z,” February 17, 2017. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/united-states-income-tax-treaties-a-to-z

[30] Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Kimberly A. Clausing “Problems with Destination-Based Corporate Taxes and the Ryan Blueprint,” U of Michigan Law & Econ Research Paper No. 16-029. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2884903

[31] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Congress Should End “Deferral” Rather than Adopt a “Territorial” Tax System,” March 23, 2011. http://www.ctj.org/pdf/internationalcorptax2011.pdf

[32] Economic Policy Institute and Americans for Tax Fairness, “Corporate tax chartbook,” September 19, 2016. http://www.epi.org/publication/corporate-tax-chartbook-how-corporations-rig-the-rules-to-dodge-the-taxes-they-owe/

[33] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: The Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” May 14, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php

[34] Richard Phillips, “Congress Should Pass the Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act to Combat International Tax Avoidance,” Tax Justice Blog, January 27, 2015. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2015/01/congress_should_pass_the_stop.php

[35] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Addressing the Need for More Federal Revenue,” July 8, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/07/addressing_the_need_for_more_federal_revenue.php

[36] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Tax Reform Details: An Example of Comprehensive Reform,” October 23, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/pdf/taxreformdetails.pdf