Key Findings

- Local income taxes can diversify revenue streams, make local tax systems more progressive, and give municipalities more fiscal autonomy and stability.

- Counties, cities, and school districts in 15 states currently use local income taxes, with over 7,000 taxing districts receiving some local income tax revenue. There are thousands of other municipalities that could be using local income taxes but aren’t.

- Local income taxes make up one-quarter of tax revenues among municipalities that collect them, often displacing regressive sales taxes.

The Benefits of Local Income Taxes

Local income taxes can be more progressive than other options available to municipalities. Many taxes available to municipalities — like sales, tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol taxes, or service and licensing fees — apply to everyone regardless of their ability to pay them. These taxes are broadly regressive, with low-income residents paying a larger share of their incomes than high-income residents.[1]

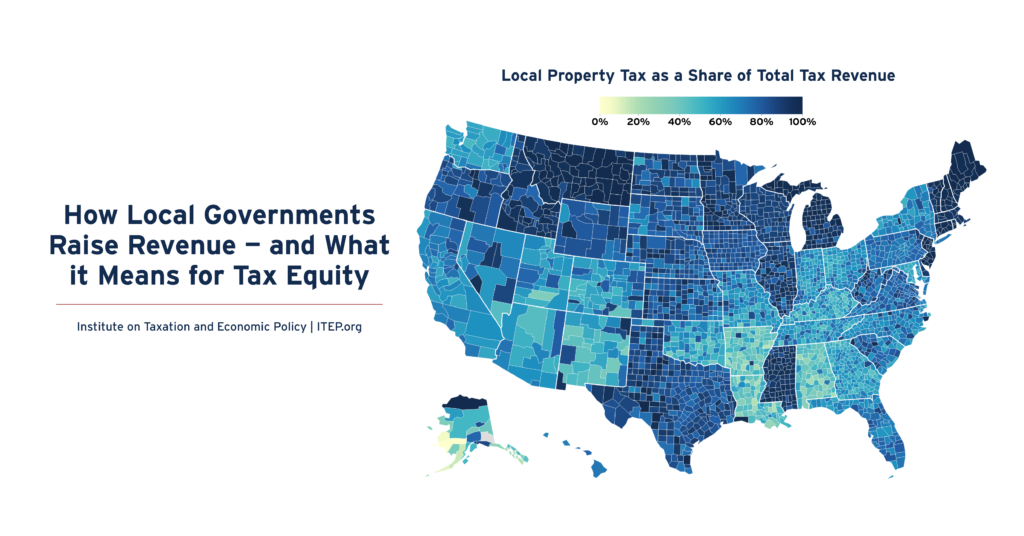

Meanwhile, property taxes are the largest source of revenue for 94 percent of local governments in the U.S.[2] Property taxes are a stable and efficient way for local governments to raise revenue, and, though not based on ability to pay, they can be relatively progressive because property wealth is loosely correlated with ability to pay. However, low- and middle-income households spend a much larger portion of their incomes on housing costs including property taxes than higher-income households. Additionally, the property tax system is marred by unequal assessments, appeals from wealthy homeowners, and historical inequities in the property market that have led to a somewhat regressive property tax system.[3]

Given the broadly regressive tools currently in use at the local level, a more progressive levy – like an income tax – can help municipalities increase revenues more equitably. Income taxes can have flat or graduated tax rates. Graduated tax rates feature higher marginal rates, charging high-income families more than lower-income families. Flat tax rates charge high- and low-income families the same rate on their taxable income. When progressive rates are combined with programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, the income tax is the most effective tool for creating a progressive tax code.

Income taxes are also inherently linked to the ability to pay. Sales and property taxes are levied regardless of whether the person paying can afford them. Income taxes are a tax directly on income. This also means that if someone is out of work and not collecting income, they do not pay the tax.

Income taxes can diversify revenue streams and give municipalities more fiscal autonomy. Revenue diversity supports fiscal stability for cities and towns of all sizes.[4] During the Great Recession, local governments across the country struggled with declining property tax revenue. Many adopted new sales taxes or raised tax rates to make up for the gap. The increased reliance on sales taxes hurt municipalities when Covid-19 hit, and many cities suffered declines in revenue.

It is more efficient for governments to have multiple streams of revenue, and especially to have offsetting revenue streams that can respond with higher revenues when other taxes lag. Diversifying revenue can also help reduce tax rate competition between municipalities, which makes all municipalities worse off. Additionally, local income taxes can improve the administration of property tax circuit breaker programs to ensure low-income homeowners can stay in their homes.[5]

Local income taxes can also ensure that all residents in an area benefit from that area’s economic gains. Companies intentionally choose to do business in municipalities that have a well-educated labor pool (such as North Carolina’s Research Triangle), reliable transportation (such as the Port of New York and New Jersey), or other advantages that stem from being in a particular area. This is what economists call agglomeration economics; agglomeration is the clustering of firms in a given geographic area, and agglomeration economics are the mechanisms that cause geographic clustering.[6] The result of agglomeration is that businesses often earn higher profits.[7] There is evidence that higher paid workers are more likely to benefit from business and amenity agglomerations so charging these workers a small tax on the benefit they receive makes sense.

Types of Local Income Taxes

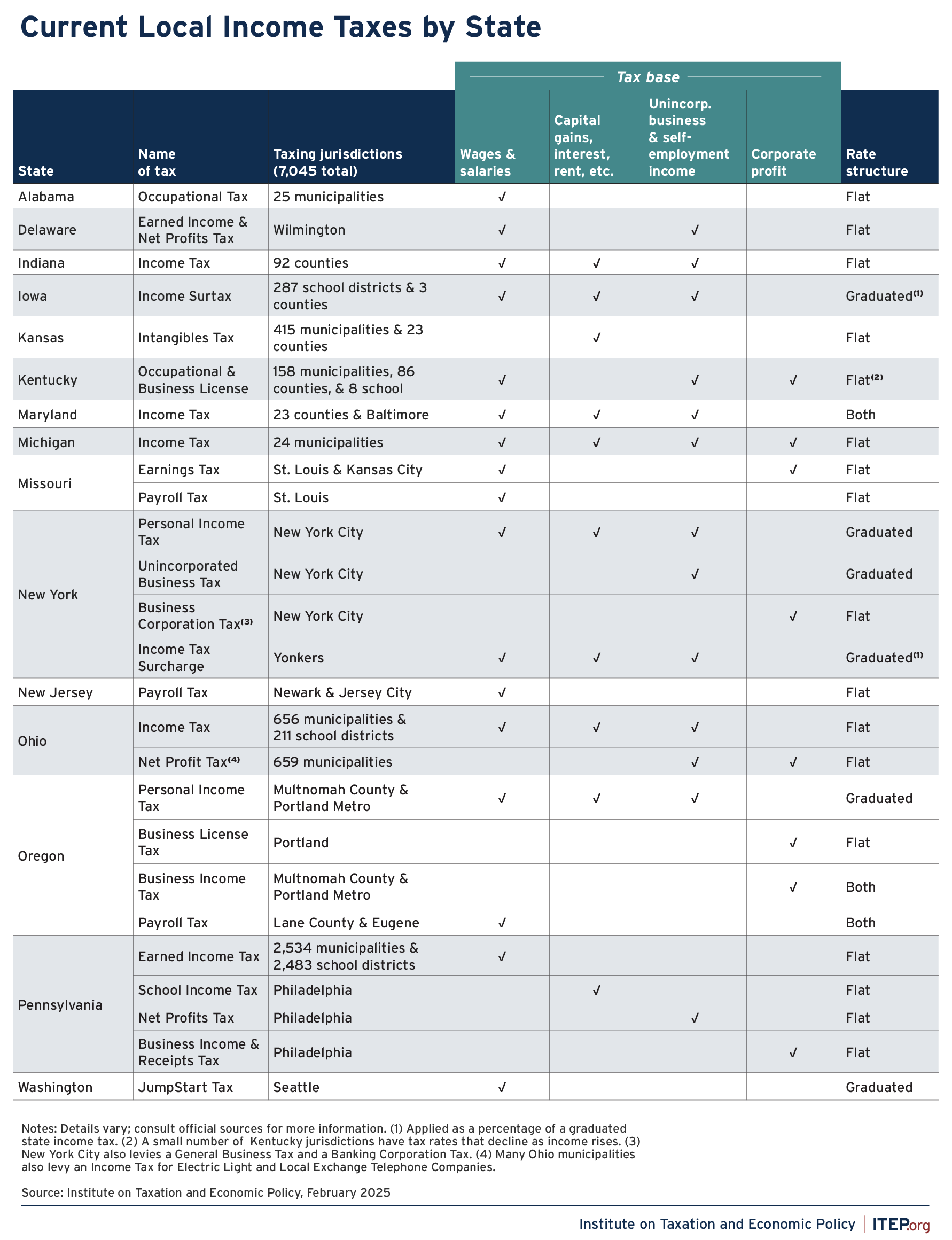

Across the U.S., 7,045 taxing districts in 15 states and the District of Columbia1 levy taxes on personal income, capital gains, business gains, or corporate profits, our analysis finds. Iowa, Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania allow a combined 2,989 school districts to collect local income taxes. States allow municipalities to tax where a person works or lives, with Delaware, Ohio, and Pennsylvania allowing municipalities to tax both where someone works and lives.

1ITEP considers Washington, DC a state in our coverage of state and local taxation issues.

The table below describes the jurisdictions that use local income taxes, what types of income are taxed, and whether the funds are collected locally or by the state. Wages and salaries are taxed in most jurisdictions. Capital gains, business income, and corporate income are also taxed in some places. Most local income taxes have a flat rate, but some municipalities, like New York City, use graduated tax rates. The most progressive taxes capture multiple forms of income and use progressive rates, like in Iowa. Administrative burdens can be minimized by state collection of local income taxes, like in Maryland.

Personal Income Taxes

Personal income taxes include any tax on earned, unearned, or pass-through income. States with personal income taxes generally tax a near-universal definition of income borrowed from federal tax law, which in turn means there’s an easily administrable, near-universal tax base available for localities to use. Tax rates may be flat or graduated. New York City, Multnomah County, Oregon, and parts of Maryland all have graduated tax rates.

Multiple states collect personal income tax at the state level and remit it to municipalities who levied their own tax. This is easier administratively for companies and workers who only deal with one set of withholdings, as well as for municipalities who do not have to collect or audit taxes on their own.

Payroll Taxes

Payroll taxes, also called earnings taxes or payroll expense taxes, are taxes on the total amount of wages a company pays.

Some of the oldest payroll taxes in the country were designed to help cities harmed by white flight. As residents – particularly higher-earning, white residents – left the city for growing suburbs, cities suffered falling property values and sales tax revenues. By taxing the working location of these commuters, cities ensure that companies reliant on commuting employees continued to pay for a share of city services.[8]

Payroll taxes typically only tax wages and salaries, not other forms of employee compensation like deferred compensation, dividends, or stock options.2 Rates can be flat or graduated. Seattle and Eugene, Oregon both have rates that increase based on the compensation of individual employees.

2There are exceptions to this; St. Louis could tax stock options, but as of 2024 does not.

A Note on Head Taxes

Head taxes, also called business occupation or occupational privilege taxes, are taxes on each individual employee working at a given location. Generally, these are a fee per employee, or “head,” at each location. Economists usually consider these to be business taxes rather than income taxes, as they are not based on income received.

Multiple cities in Colorado — including Denver,[9] Aurora,[10] and Glendale[11] — levy head taxes. Pennsylvania allows municipalities and school districts to levy a head tax called the local services tax.[12] Illinois and Washington both allow municipalities to levy head taxes, but no cities in either state currently use them. Head taxes can distort local labor markets by disincentivizing hiring workers, as businesses are taxed regardless of the salary earned by those employees. Head taxes can also push down wages as companies have to pay taxes to employ workers at all.[13]

Corporate Income Taxes

Corporate income taxes are taxes on net profit. Corporate income taxes are not common in local government, due mostly to state law prohibitions or preemption.

Michigan, Missouri, and Pennsylvania allow municipalities to tax corporate income. New York City has a corporate income tax that applies to all corporations and banks other than federal S-corporations.[14]

Common Criticisms of Local Income Taxes Are Overblown

Critics of local income taxes raise concerns about the theory and the implementation of a local income tax, but these concerns do not hold water.

First, some argue that businesses or residents may leave an area in response to the creation of a local income tax. While there is some evidence that in the immediate aftermath of the creation there may be some exits, the numbers are small. Businesses frequently overstate the importance of local taxes in order to extract tax cuts from municipalities and states. Research has shown that taxes are a relatively small portion of expenses for businesses, and that other concerns around labor availability, material costs, and connections to other businesses have a much higher impact on how companies spend money.[15]

In addition, municipalities are already competing with one another for residents and businesses on tax systems and on services and amenities offered. A new local income tax may rebalance the mix of taxes already used by a municipality and may result in lower property or sales tax rates. Tax competition can be mitigated by statewide adoption, like in Ohio and Pennsylvania, or by state administration, like in Maryland and Indiana.

Second, critics raise administrative concerns about how a municipality could levy and collect local income tax. Municipalities may have to stand up a collection and audit system, which could be costly without state assistance. Some larger cities clearly have substantial capacity on their own. However, cities need not create a system completely from scratch. Localities can look to the federal income tax, or the state income tax if it exists, for information and help with enforcement. States could provide assistance to smaller localities, or those localities can use simple structures, such as a fixed percentage of state or federal tax due.

There is also a lot of handwringing about double taxation. And yes, residents may be double taxed in their home and where they work. Non-residents may be taxed in a state they do not live in. But these income taxes are supporting vital city services offered to residents and commuters alike. While double taxation is an issue in some places, states can ensure that residents are taxed on their income once. Ohio allows individuals to be taxed at their homes and at their workplaces and allows individuals to credit these taxes paid to the other municipality.

Some raise concerns about how remote work can complicate “where” someone works. Even assuming that the increase in remote work is permanent, this primarily means that jurisdictions need to develop reasonable new means of dividing up income between them. For example, if a worker works in the office 60 percent of the time, then perhaps the site of the worker’s office would only be able to tax 60 percent of their income, with 40 percent going back to the residence jurisdiction. Because administrable and reasonable solutions are available, the change in work patterns is not a good reason not to adopt local income taxes.[16]

Further, the decline of commercial real estate in many cities because of the rise of remote work strengthens the argument for local income taxes. To deal with falling property tax revenues, some cities are shifting more of the property tax levy onto commercial properties, while others are simply dealing with higher property tax bills for residents.[17] A small local income tax is a more fair and efficient choice than increasing property taxes on struggling commercial landlords or increasing property taxes on all residents regardless of ability to pay.

The bottom line is that local income taxes are an effective way for municipalities to fund city services without penalizing low-income residents. While this may be different for every municipality, multiple options are viable depending on state law preemption or limitation.

Building Effective and Progressive Local Income Taxes

Many cities and states in the U.S. already levy local income taxes. These examples highlight some best practices across the country.

Maryland

Maryland has a comprehensive, statewide program of local income taxation that promotes progressivity at the local level, eliminates double taxation for residents, and offers a substantial revenue source for county governments.

All residents in Maryland are charged a local income tax rate based on where they live. People who work in Maryland but live outside the state still pay the tax, but it is kept by the state. Each county and the city of Baltimore selects its own tax rate. Two counties, Anne Arundel and Frederick, have progressive marginal rates depending on income and family size. The state administers the collection and distribution of tax revenues on behalf of counties, which simplifies local income taxes for residents, businesses, and counties and also allows for easier application of local refundable credits, like the Earned Income Tax Credit or Child Tax Credit. Montgomery County, Maryland, has a local EITC.[18]

The local income tax in Maryland provides a substantial portion of revenue for the counties that collect them. State law requires county tax rates to be set between 2.25 and 3.2 percent, which accounts for between 12 and 43 percent of county tax revenue.[19] This map of Maryland shows a county-by-county look at how much revenue their local income tax generates.

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, like many cities and school districts in Pennsylvania, levies a local income tax, as well as a payroll expense tax. Local income – which includes wages, salaries, self-employment income, and net profits - is taxed at 3 percent, with 1 percent going to the city of Pittsburgh, and 2 percent going to the school district.3 Payroll expenses are taxed at 0.55 percent on the total payroll of all businesses in the city. Local income taxes are levied on residents, and payroll expense taxes are levied on businesses in city limits.[20] This tax has enabled the city to maintain a relatively low local sales tax rate of only 1 percent and makes up over 20 percent of the school district revenue.

3The school district itself remits 0.25 percent of their rate back to the city of Pittsburgh, which effectively means the city has a 1.25 percent rate and the school district has a 1.75 percent rate.

In 2023, ITEP partnered with the Keystone Research Center to explore expanding Pittsburgh’s income tax to include unearned income, which includes dividends, interest, and capital gains. We found that a 1 percent tax on unearned income would generate nearly $22 million per year and that the top quintile of earners (families making more than $134,000 per year) would pay 90 percent of the tax due to the city regardless of the rate of taxation. Over 60 percent of all tax revenue would be levied on the top 1 percent of earners in the city – households making more than $783,000 per year.[21]

The benefits of an unearned income tax could be extremely consequential for cities and towns across the country. Pittsburgh’s current local income tax and payroll expense tax accounted for 24 percent of the city’s total revenue in fiscal 2023.[22] Expanding the tax to include unearned income could help lower-income Pittsburghers by shifting the tax base to wealthier residents and taking pressure off the earned income tax.

Seattle

Seattle’s payroll expense tax, commonly referred to as the JumpStart tax, supports local affordable housing development, small business development, and the city’s general fund.[23] It is a payroll expense tax paid by employers levied on high earners employed by businesses with a certain amount of revenue every year. The base amount of payroll expenses and the lowest taxable salary are adjusted every year to account for inflation.[24]

The tax is designed to protect small firms and low- and middle-income earners. Since businesses only pay the tax on high earners, it is more likely to protect lower-income people working for large corporations, especially those working at large retail or food service jobs. In addition, Washington’s constitution does not allow for a personal income tax.[25] Local leaders determined that a payroll tax would be legal and passed this innovative tax through the city council.

States Should Allow Municipalities More Flexibility

Despite the success of local income taxes across the country, 35 states do not currently have local option income taxes. Often this is due to state-level preemptions, either in state constitutions or in statute. A survey of 50 states shows that nine – Arizona, California, Georgia, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas Wisconsin, and Wyoming – have statutes or constitutional language barring municipalities from taxing personal income. An additional seven – Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Nebraska, Rhode Island and Virginia – require municipalities to seek permission from the state legislature to levy new taxes.

Municipalities seeking to adopt local option income taxes should explore whether current state law would need to be changed. States with existing income taxes can assist municipalities by allowing districts to “piggyback” on their existing tax systems. This simplifies collection for municipalities, businesses, and individuals.

Not all states levy a state income tax. Adoption of local income taxes in those states may be more administratively complicated if municipalities must collect and audit taxes themselves. But there are still opportunities for innovation in local income taxes. For instance, Seattle successfully created its JumpStart tax without the permission of the Washington statehouse, as they used their authority as a city.

There is even opportunity in states with income taxes to broaden their usage. Alabama, Missouri, and New York only allow specific municipalities to tax income. These states could broaden their statutory language to enable more cities and counties to access these revenue streams.

While some states share income tax revenue with municipalities, states often have a lot of power in deciding how much municipalities receive each year. States interested in helping their municipalities grow tax revenue without relying on regressive options should consider allowing municipalities to tax income. Local income taxes can be an important progressive revenue raiser, as they ask more of higher-income households and are connected to ability to pay. They can raise substantial revenue to fund key public services to make cities and regions better off.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for their generous support of this project. A special thanks to Andrew Boardman for the initial research for this brief. We also extend gratitude to the policymakers who shared their knowledge including Stephen Herzenberg from the Keystone Research Center, Christopher Meyer from Maryland Center on Economic Policy, Katie Wilson from the Transit Riders Union, and Darien Shanske of the UC Davis School of Law. A huge thanks also to my ITEP colleagues, particularly Alex Welch, Jon Whiten, Matt Gardner, and Amy Hanauer for their contributions to this report.

Endnotes

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” January 2024.

[2] Rita Jefferson and Galen Hendricks. "How Local Governments Raise Revenue – And What it Means for Tax Equity,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Dec. 5, 2024.

[3] Christopher Berry. ”Reassessing the Property Tax,” draft dated Mar. 1, 2021.

[4] Erin Adele Scharff and Darien Shanske. “The Surprisingly Strong Case for Local Income Taxes in the Era of Increased Remote Work,” UC Law Journal vol. 74, no. 3 (2023).

[5] Carl Davis and Brakeyshia Samms. "Preventing an Overload: How Property Tax Circuit Breakers Promote Housing Affordability,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 11, 2023.

[6] Kathleen Bolter and Jim Robey. “Agglomeration Economies: A Literature Review,” The Fund for Our Economic Future, Jun. 30, 2020.

[7] Scharff and Shanske 2021.

[8] Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. “The Commuter and the Municipal Income Tax,” Apr. 1970; Michael R. Merz. “Municipal Personal Income Taxation of Nonresidents,” Ohio State Law Journal (1970) vol. 31, pp. 770-805.

[9] City and County of Denver, Colorado. “Topic No. 61: Occupational Privilege Taxes (OPT or Head Tax),” Revised Jul. 2017, accessed Jul. 25, 2024.

[10] Aurora, Colorado. “Occupational Privilege Tax,” Accessed Jul. 25, 2024.

[11] Glendale, Colorado. “Occupational Privilege Tax,” accessed July 25, 2024.

[12] Edmund W. Appleton. "The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Antiquated and Oft-Abused Occupation Tax: A Call for Abolition,” University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Caveat vol. 46 no. 7 (2012).

[13] Jared Bernstein. "Why the Seattle ’head tax’ is relevant to the nation,” Washington Post, May 16, 2018.

[14] New York City Department of Finance. “Business corporation tax,” Accessed Jul. 24, 2024.

[15] Emily Birnbaum. “Tech looks for lessons from Amazon HQ2 fight,” The Hill, Feb. 17, 2019.

[16] Kim Parker. “About a third of U.S. workers who can work from home now do so all the time,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 30, 2023.

[17] Ashley Fahey. “Property tax assessments are surging – but some owners are getting hit even harder,” Albany Business Review, Jul. 24, 2024.

[18] Kamolika Das, Andrew Boardman, and Galen Hendricks. “Local Earned Income Tax Credits: How Localities Are Boosting Economic Security and Advancing Equity with ETICs,” ITEP, Oct. 30, 2023.

[19] Comptroller of Maryland. “Maryland Income Tax Rates and Brackets,” Accessed Jan. 13, 2024.

[20] The City of Pittsburgh Department of Finance. “Tax Descriptions,” accessed Jul. 29, 2024.

[21] Nthando Thandiwe and Stephen Herzenberg. “Fair Taxation Can Help Achieve a More Just Pittsburgh,” Dec. 12, 2023,

[22] City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “Annual Comprehensive Financial Report Year Ended December 31, 2023,” accessed Jul. 26, 2024.

[23] Katie Wilson. "Op-Ed: Washington State’s Path to Tax The Rich in 2025," The Urbanist, January 6, 2025. https://www.theurbanist.org/2025/01/06/op-ed-washington-states-path-to-tax-the-rich-in-2025/

[24] Seattle City Finance. “Payroll Expense Tax,” Accessed Jul. 30, 2024.

[25] Carol Adolph. “The Strange, Short Story of Washington State’s Income Tax,” KUOW, Oct. 18, 2015; Washington Secretary of State. “Income Tax Ballot Measures,” accessed Jul. 26, 2024.