Colorado has struggled to adequately finance its K-12 education system for more than two decades, in large part because of tight restrictions on tax revenue growth built into the state’s constitution. Colorado voters will be given the opportunity to change that this November by raising nearly $1 billion in new income tax revenues for education each year. The proposal (Amendment 66) would accomplish this goal by converting the state’s flat income tax into a two-tiered, graduated rate income tax.1 As this report shows, this change would somewhat reduce the steep regressivity of Colorado’s overall tax system. In other words, taxpayers across all income levels would pay a more equal share of their income if Amendment 66 is approved, in large part because most of the revenue raised by the amendment would come from the wealthiest 20 percent of Colorado residents.

AMENDMENT 66 WOULD REDUCE TAX REGRESSIVITY

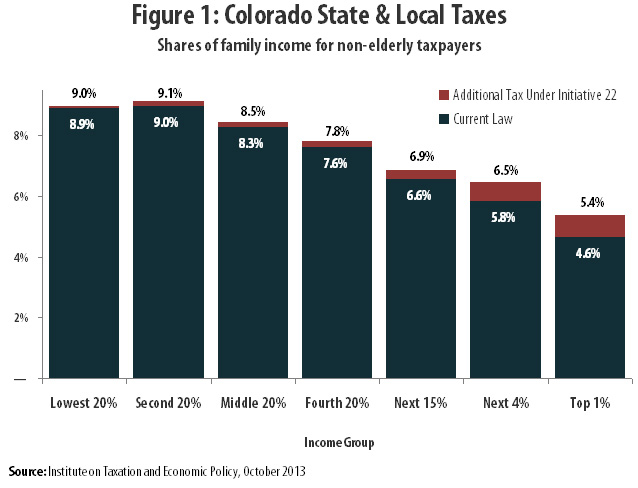

Looking at all of Colorado’s major taxes (including state and local sales, income, and property taxes), the state’s highest earners currently pay a much smaller share of their income in tax (4.6 percent) than the lowest earners (8.9 percent). This is due primarily to Colorado’s sales tax, which tends to hit low-income families hardest since those families must spend most or all of what they earn on items subject to tax just to get by.2 While Colorado’s poorest residents spend an average of 5.6 percent of their income on sales and excise taxes, the state’s most affluent residents spent just 0.8 percent. Most states partially compensate for the lopsided impact of the sales tax with a graduated personal income tax that applies higher tax rates to higher levels of income. Colorado’s personal income tax, however, uses just one flat rate (4.63 percent) and is therefore less effective than most in equalizing the distribution of the state’s tax system.

Looking at all of Colorado’s major taxes (including state and local sales, income, and property taxes), the state’s highest earners currently pay a much smaller share of their income in tax (4.6 percent) than the lowest earners (8.9 percent). This is due primarily to Colorado’s sales tax, which tends to hit low-income families hardest since those families must spend most or all of what they earn on items subject to tax just to get by.2 While Colorado’s poorest residents spend an average of 5.6 percent of their income on sales and excise taxes, the state’s most affluent residents spent just 0.8 percent. Most states partially compensate for the lopsided impact of the sales tax with a graduated personal income tax that applies higher tax rates to higher levels of income. Colorado’s personal income tax, however, uses just one flat rate (4.63 percent) and is therefore less effective than most in equalizing the distribution of the state’s tax system.

Amendment 66 changes this fact by replacing Colorado’s flat rate personal income tax rate with a two-tiered system: the rate on taxable income under $75,000 would rise from 4.63 percent to 5.0 percent, and the rate on incomes over that amount would rise to 5.9 percent. The result would be a noticeable reduction in the gap in overall tax rates seen by residents at different income levels. While taxes paid would increase as a share of family income for all income groups, the lowest 20 percent of earners would see just a 0.1 percent increase, while the top 1 percent of earners would see a 0.8 percent increase. Colorado’s tax system would be made somewhat less unfair if Amendment 66 is approved by voters.

REVENUE CONTRIBUTION BY MOST COLORADANS WOULD BE COMPARATIVELY MODEST

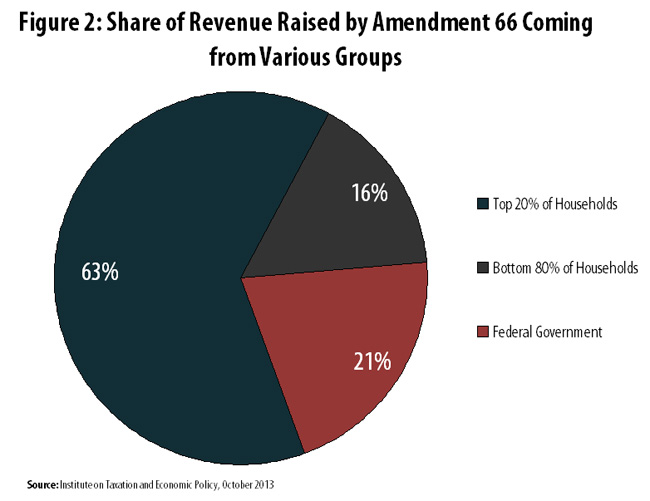

While most families would contribute more to paying for education under Amendment 66, the reform is designed in a way that raises the bulk of its revenue from those taxpayers best able to afford additional taxes. Almost two-thirds (63 percent) of the revenue raised by Amendment 66 would come from the wealthiest 20 percent of Colorado taxpayers.

While most families would contribute more to paying for education under Amendment 66, the reform is designed in a way that raises the bulk of its revenue from those taxpayers best able to afford additional taxes. Almost two-thirds (63 percent) of the revenue raised by Amendment 66 would come from the wealthiest 20 percent of Colorado taxpayers.

Another 21 percent of the revenue would not come from Colorado residents, but from the federal government in the form of larger deductions for state income taxes paid. In other words, if Colorado voters decide to raise their state income tax, many of those same voters (those who claim itemized deductions) will see their federal tax bills shrink when they write-off those larger state income payments on their federal tax returns.3 As a result of this interaction with federal tax law, roughly one in five tax dollars raised by Amendment 66 would be offset for Colorado taxpayers by a cut in their federal taxes.

COLORADO’S EDUCATION SPENDING HAS LAGGED THE NATION FOR DECADES

While the above discussion makes clear who would provide the revenue raised by Amendment 66, the more fundamental issue is why the state’s education system is in need of that additional revenue.

In 1992, Colorado spent $330 less per pupil on education than the national average (ranking 30th in the nation). By 2011, that gap had widened to $1,836 less than average (dropping its ranking to 42nd).4 As a result, Colorado classrooms have become increasingly overcrowded, with the state’s student-to-teacher ratio routinely ranking in the mid-40s nationally.5 Teacher salaries have been affected as well, trailing the national average by 2 percent since 2000, and actually decreasing by 0.6 percent when measured relative to inflation over this period.6

It is no mystery as to why Colorado’s education finances are in such disarray. The state’s tax collections have been severely restrained by the Taxpayer Bill of Rights (known as TABOR) contained in the state’s constitution. By requiring voter approval for most revenue-raising bills, and by tightly capping revenue collections based on growth in inflation plus population, TABOR has made it nearly impossible for Colorado to collect adequate revenue for education and other public services.7

Amendment 66 would at least partially address this problem by amending the state’s constitution to allow for roughly $1 billion in new income tax revenues each year in order to improve K-12 education in underserved communities, decrease class sizes, increase access to kindergarten, and strengthen special education programs.8

CONCLUSION

Colorado’s current tax system falls short in at least two important ways: it raises insufficient revenue to adequately fund education, and it requires that lower- and middle-income Coloradans pay taxes at a higher effective rate than more affluent residents. If approved by voters this November, Amendment 66 would at least partially address both of these shortcomings. It would do this by raising nearly $1 billion for public schools each year, and by collecting most of that revenue from the upper-income taxpayers that currently devote less of their household budgets to paying Colorado taxes than any other group.

1 Prior to being placed on the ballot, this proposal was known as Initiative 22.

2 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “How Sales and Excise Taxes Work.” July 1, 2011. https://itep.org/itep_reports/2011/07/how-sales-and-excise-taxes-work.php

3 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “How State Tax Changes Affect Your Federal Taxes: A Primer on the ‘Federal Offset’.” August 1, 2011. http://itep. org/itep_reports/2011/08/how-state-tax-changes-affect-your-federal-taxes-a-primer-on-the-federal-offset.php

4 U.S. Census Bureau Public School Finance Data. www.census.gov/govs/school/

5 National Center for Education Statistics. http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_078.asp

6 National Education Association. Rankings and Estimates: Rankings of the States 2011 and Estimates of School Statistics 2012 www.nea.org/assets/docs/NEA_ Rankings_And_Estimates_FINAL_20120209.pdf

7 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “A Closer Look at TABOR.” August 19, 2013. https://itep.org/itep_reports/2013/08/a-closer-look-at-tabor-taxpayer-bill-of-rights.php

8 Center for American Progress. “School-Finance Reform: Inspiration and Progress in Colorado.” June 3, 2013. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education/report/2013/06/03/64996/school-finance-reform-inspiration-and-progress-in-colorado/