Alaska’s tax system underwent major changes in the 1970s when oil was found at Prudhoe Bay. Lawmakers repealed the state’s personal income tax (making Alaska the only state ever to do so) and began balancing the state’s budget primarily with oil tax and royalty revenue instead. But as oil prices and production levels have declined, a yawning gap has opened between state revenues and the cost of providing vital public services.

While at one point it was feasible for Alaska to rely on oil revenues, falling collections from that industry will require flexibility and tough choices. Alaska’s problems are unique in their scale, but they should look familiar in many states across the country that are dealing with the fallout from tax cuts.

Over the last several years, ITEP has helped inform Alaska’s ongoing debate over new revenue sources that could replace declining oil revenues. The magnitude of the state’s fiscal problems likely calls for one of the two major taxes levied by most other state governments: either reinstating a personal income tax or enacting a statewide general sales tax instead.

As recently as 2017, the Alaska House passed a personal income tax bill that then-Gov. Bill Walker would almost certainly have signed into law. But the legislation died in the Senate and has yet to be taken up in a serious way since then. Talk of broad-based taxation has continued to simmer, however.

Last month, I was honored to be able to take part in that discussion as part of the Alaska Municipal League’s winter legislative conference in Juneau. My presentation included a nuts and bolts description of both personal income and sales taxes, but I also pointed out the multitude of advantages that income taxes enjoy relative to general sales taxes.

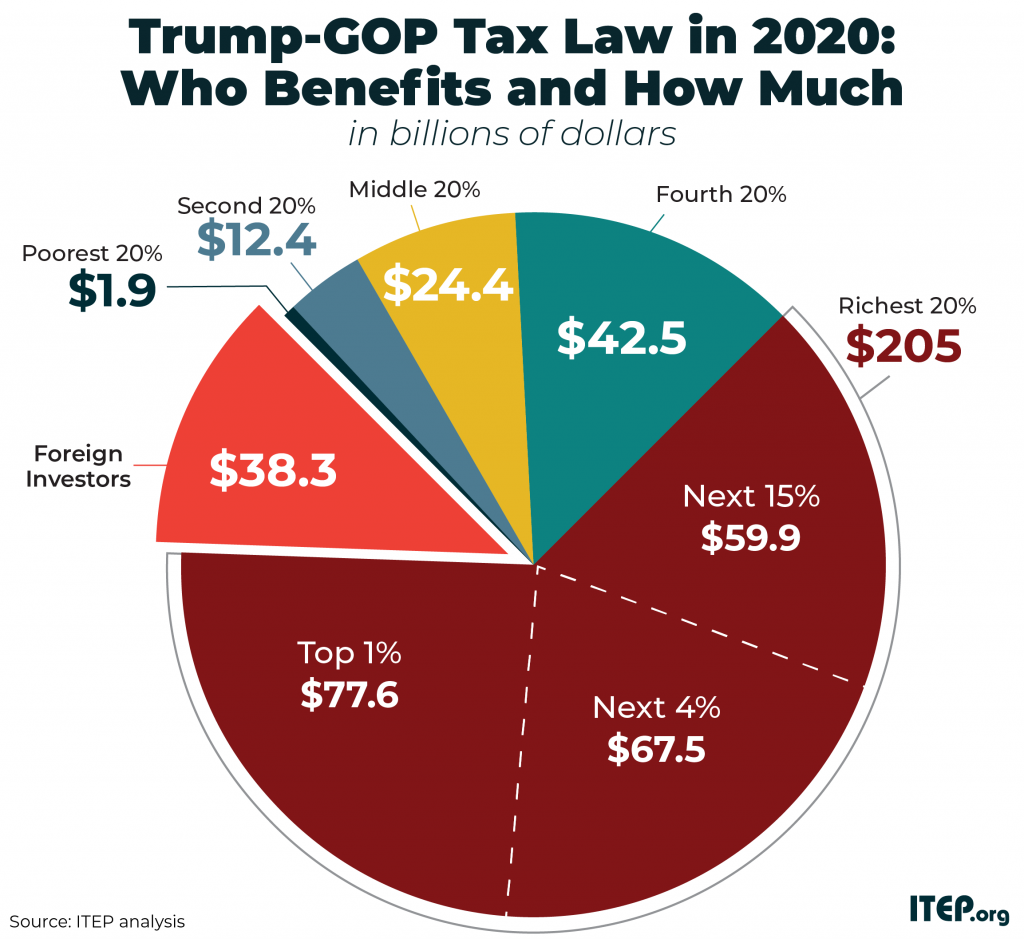

The most obvious benefit of income taxes is that they can be calibrated based on ability to pay. Under a personal income tax, families with high incomes can be taxed at higher rates than the middle-class, and exemptions or credits can prevent impoverished families from being taxed deeper into poverty. This progressive structure is particularly valuable in the wake of the 2017 federal tax overhaul, which cut taxes steeply for high-income earners. If Alaska lawmakers are interested in recapturing some of the $340 million federal tax cut windfall that we estimate the state’s top 5 percent of earners will receive this year, a progressive personal income tax is the best way to do it.

In an age of widening income inequality, progressive income taxes are also likely to generate more meaningful revenue growth over time than regressive sales taxes, since income taxes ask more of those high-income families whose incomes are growing fastest.

And because income taxes raise significantly more revenue from the wealthy, these taxes also allow for lower effective tax rates on most people, relative to a sales tax. A study conducted by researchers at the University of Alaska Anchorage, for instance, found that eight in 10 Alaskans would pay less under a progressive income tax than under a sales tax designed to raise the same amount of revenue. ITEP reached a similar conclusion in its study of two somewhat different income and sales tax options.

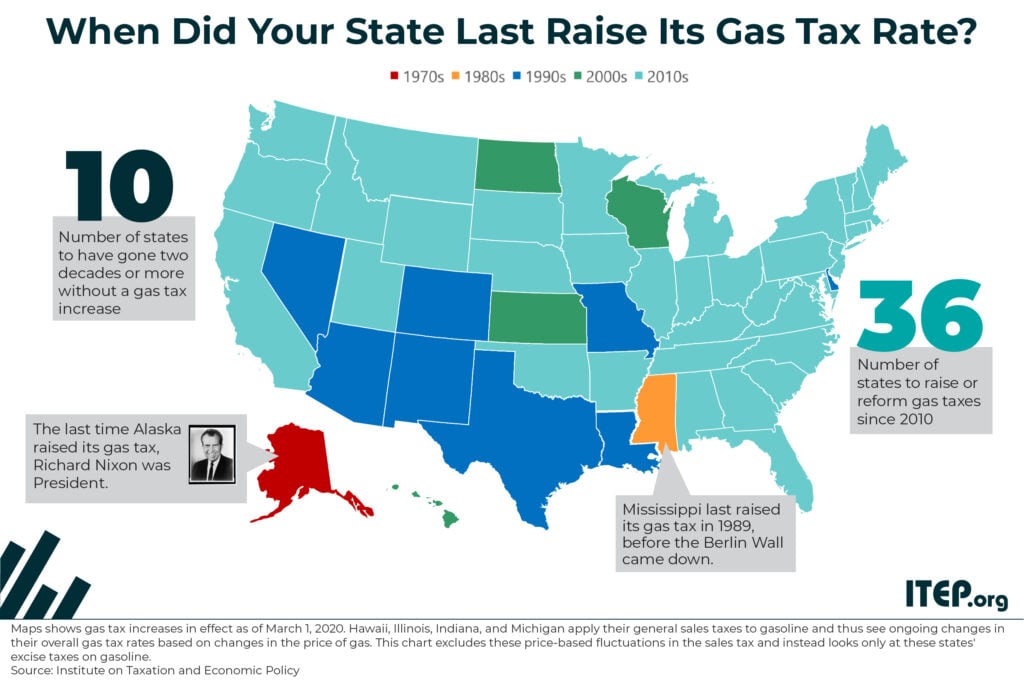

For the time being, Alaska lawmakers are most interested in modest revenue options seen as politically feasible. An 8-cent increase in the state’s motor fuel tax rate recently passed the Senate by a wide margin, for instance. But while such an increase is long overdue (the current tax rate will mark its 50th year of stagnation of May 28th), it is only a drop in the bucket relative to the state’s revenue needs. It’s likely only a matter of time before discussion of broad-based revenue raising becomes a top legislative priority once again.