House Bill’s Deduction for Car Loan Interest Would Not Offset Tariff-Related Auto Price Increases for Most Buyers

briefSummary

This analysis examines the extent to which a temporary income tax deduction for vehicle loan interest that recently passed the U.S. House of Representatives would be able to offset higher vehicle prices caused by recent increases in U.S. tariffs.

- Many buyers would be ineligible for the deduction. The lowest and highest income families would typically be ineligible for the auto loan interest deduction and thus would face the full tariff price effect without any offsetting deduction. Car buyers purchasing vehicles for which final assembly took place outside of America would also be ineligible. Industry experts estimate that 80 percent of cars priced under $30,000 are imported and thus buyers of those lower-priced cars would be barred from accessing the deduction.

- The loan interest deduction is incapable of offsetting even a modest 3 percent increase in the price of vehicles assembled in America. The deduction would offset only 36 to 43 percent of tariff-induced price increases for working-class families while buyers with higher incomes could see offsets ranging up to 85 percent. On a $40,000 vehicle, the net price increase would range from $201 to $879 for eligible claimants and would be $1,363 for car buyers ineligible for the deduction.

- If prices for vehicles assembled in the U.S. rise by 5 percent, as some industry analysts expect, families who are eligible for the loan interest deduction should generally expect to see less than half of the tariff expense offset by the tax deduction. The deduction would offset 22 to 26 percent of the price increase for working-class families while buyers with higher incomes could see offsets ranging up to 52 percent. On a $40,000 vehicle, the net price increase considering the tariffs and the deduction would range from $1,087 to $1,778 for eligible claimants, with the higher end of that increase falling on car buyers with more modest incomes. Car buyers who are ineligible for the deduction would face a $2,272 price increase.

- If prices rise by 10 percent because of the tariffs, families across the board should generally expect to see no more than a quarter of that added expense offset by the loan interest deduction. The deduction would offset 11 to 14 percent of the price increase for working-class families while buyers with higher incomes could see offsets ranging up to 27 percent. On a $40,000 vehicle, the net price increase would range from $3,303 to $4,026 for eligible claimants and would be $4,543 for car buyers ineligible for the deduction.

Background

The tax and spending bill that passed the U.S. House of Representatives last month would create a new tax deduction for car loan interest, modeled after a proposal made by then-candidate Donald Trump in the waning days of the 2024 presidential campaign. Specifically, the House bill would allow tax filers to deduct up to $10,000 per year of vehicle loan interest from their incomes for tax years 2025 through 2028, so long as final assembly of the vehicle took place in the U.S.

In April, the Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on all automobiles and most automobile parts imported into the U.S. that aren’t covered by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). In weeks since, an executive order offered a two-year, partial credit against tariffs owed on parts for U.S.-assembled cars. The credit ranges up to 3.75 percent of the manufacturer’s suggested retail price for the first year and 2.5 percent for the second year.

The tax deduction was envisioned partly as a way to offset some of the price increases on vehicles caused by tariffs. But the deduction would fail to offset even minor cost increases arising from automobile tariffs and would offer little or no benefit to low-income and working-class Americans.

Tariff Price Effects

Economists at Anderson Consulting Group estimate that, even with the credit, the price of American assembled vehicles will rise by at least $2,000 because of the tariffs, with some models seeing higher increases of $10,000.[1] Cox Automotive estimates at least a 5 percent price increase in the total cost of vehicles assembled in the U.S.[2]

With these figures in mind, we use a 5 percent price increase as our central case in this brief, with 3 and 10 percent increases presented to gain a sense of the impact of smaller, or larger, potential price increases. In practice, price changes will vary across vehicle types depending on the extent to which they contain foreign parts and the ways in which consumer demand is reshaped by the tariff regime more generally.

Auto Loan Interest Deduction

The auto loan interest deduction in the House tax bill is being touted as a policy to promote purchases of American made vehicles.[3] Generally, the value of the deduction would be the taxpayer’s top marginal tax rate multiplied by the interest they paid on the loan they used to purchase a U.S.-assembled vehicle. Single filers with adjusted gross income up to $100,000 and joint filers with income up to $200,000 could deduct up to $10,000 in vehicle loan interest per year. Those at the upper end of that range would be the top beneficiaries. The cap then phases down to zero for single filers with income over $150,000 and joint filers with income over $250,000. Because of these income limits, the taxpayers who would benefit are generally paying a top marginal tax rate of 10, 12, 22, or 24 percent.

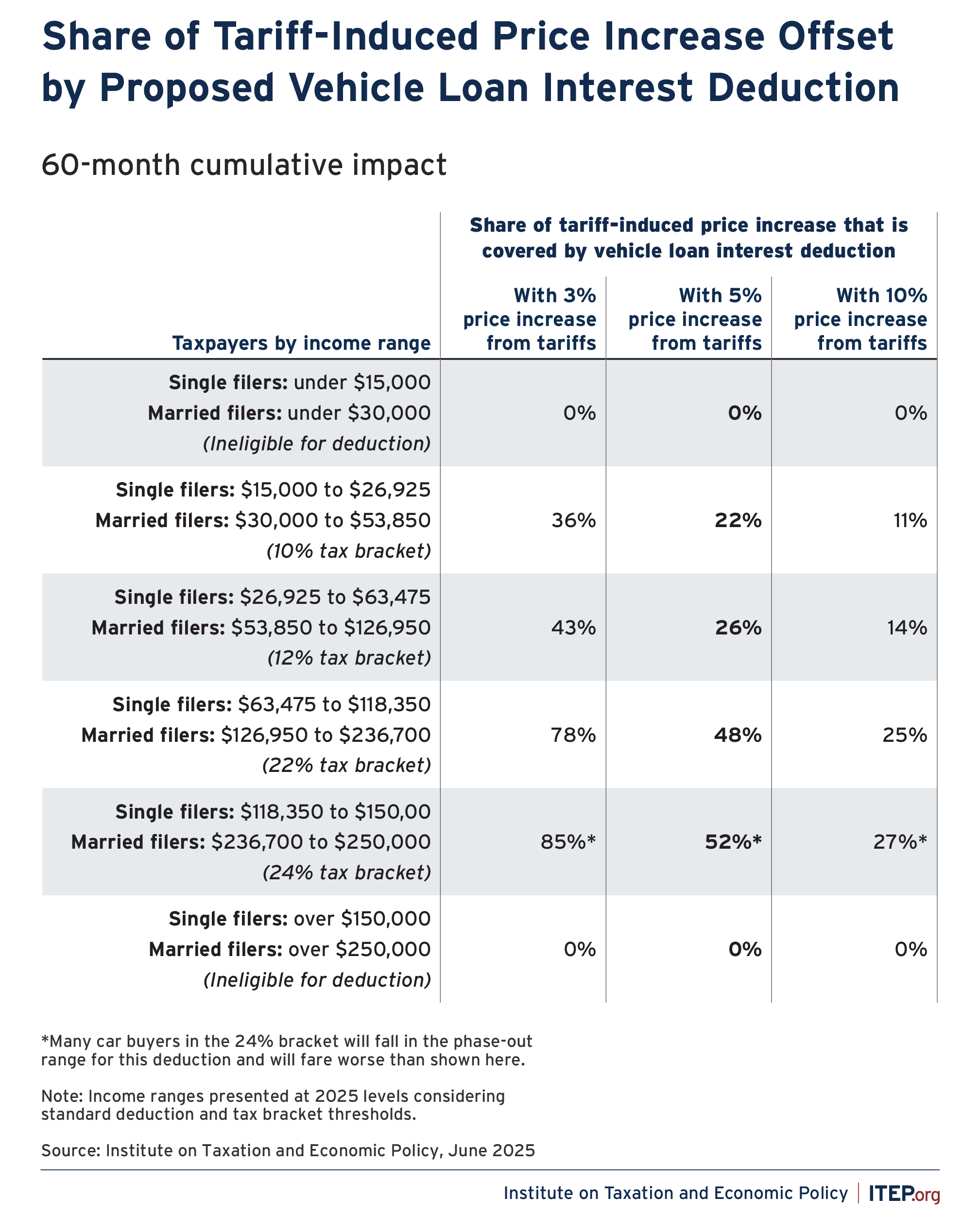

Figure 1 shows the extent to which typical car buyers should expect the loan interest deduction to offset the higher prices resulting from the tariffs. We find that buyers facing even small price increases for American assembled vehicles would not be made whole by the vehicle loan interest deduction.

For instance, if the price of an American assembled vehicle rises by 5 percent, the deduction will cancel out roughly a quarter or less of the cost of the tariff for single filers earning $63,475 or less and joint filers earning $126,950 or less. At all eligible income levels, the deduction would fail to offset even a 3 percent price increase due to tariffs, which is on the low end of economists’ expectations.

FIGURE 1

Working class families, who are expected to be most impacted by tariff-induced price increases, see little benefit from the auto loan deduction (or the House bill as a whole, for that matter).[4] The standard deduction excludes the first $15,000 of a single filer’s income from taxation in 2025, and the income tax rate is only 10 percent for the next $11,925 of income and 12 percent on the next $36,550 of income. This means the value of the deduction is between zero and 12 cents for each dollar spent on auto loan interest for single filers with income at or below $63,475. This is also the case for married filers with income up to $126,950.

For an eligible $20,000 vehicle, this is a total benefit of about $300 if the deduction is claimed for the full 2025-2028 period. However, a large share of lower priced vehicles will not be eligible for the deduction. The limitation that an eligible loan be on a U.S. assembled vehicle excludes an estimated 80 percent of vehicles priced under $30,000, according to Cox Automotive.[5]

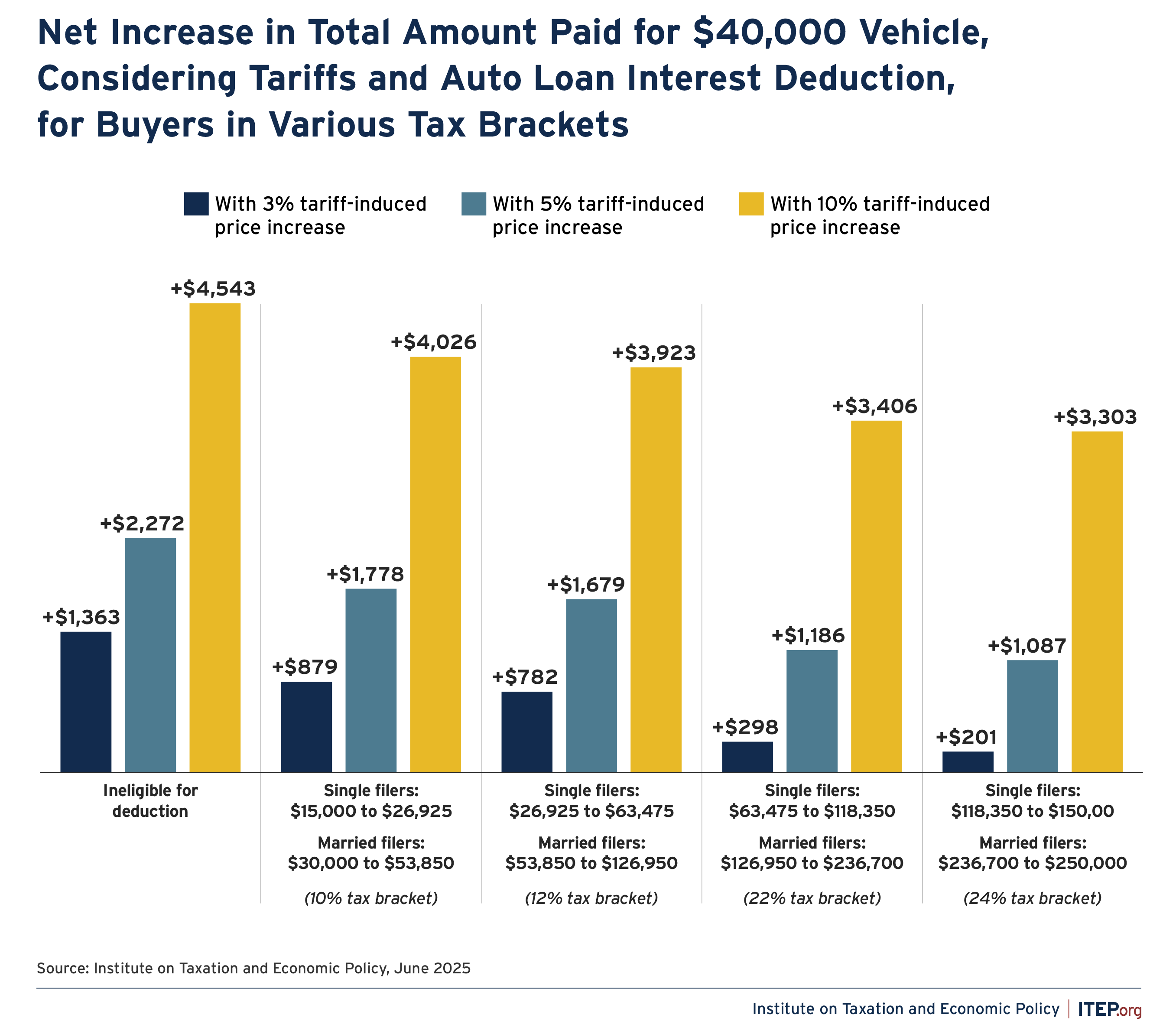

Figure 2 shows the bottom-line price change for a $40,000 U.S.-assembled vehicle after figuring in tariff price increases and the loan interest deduction. This shows the extent to which buyers of vehicles assembled in America are made worse off if the price rises because of the tariffs but the interest paid on vehicle loans becomes tax deductible. Under a scenario where car prices rise by 5 percent, for instance, deduction-eligible buyers can expect a net price increase after the deduction of between $1,087 to $1,778 and those with incomes too high or low to benefit from the deduction can expect to bear the full price increase of $2,272.

FIGURE 2

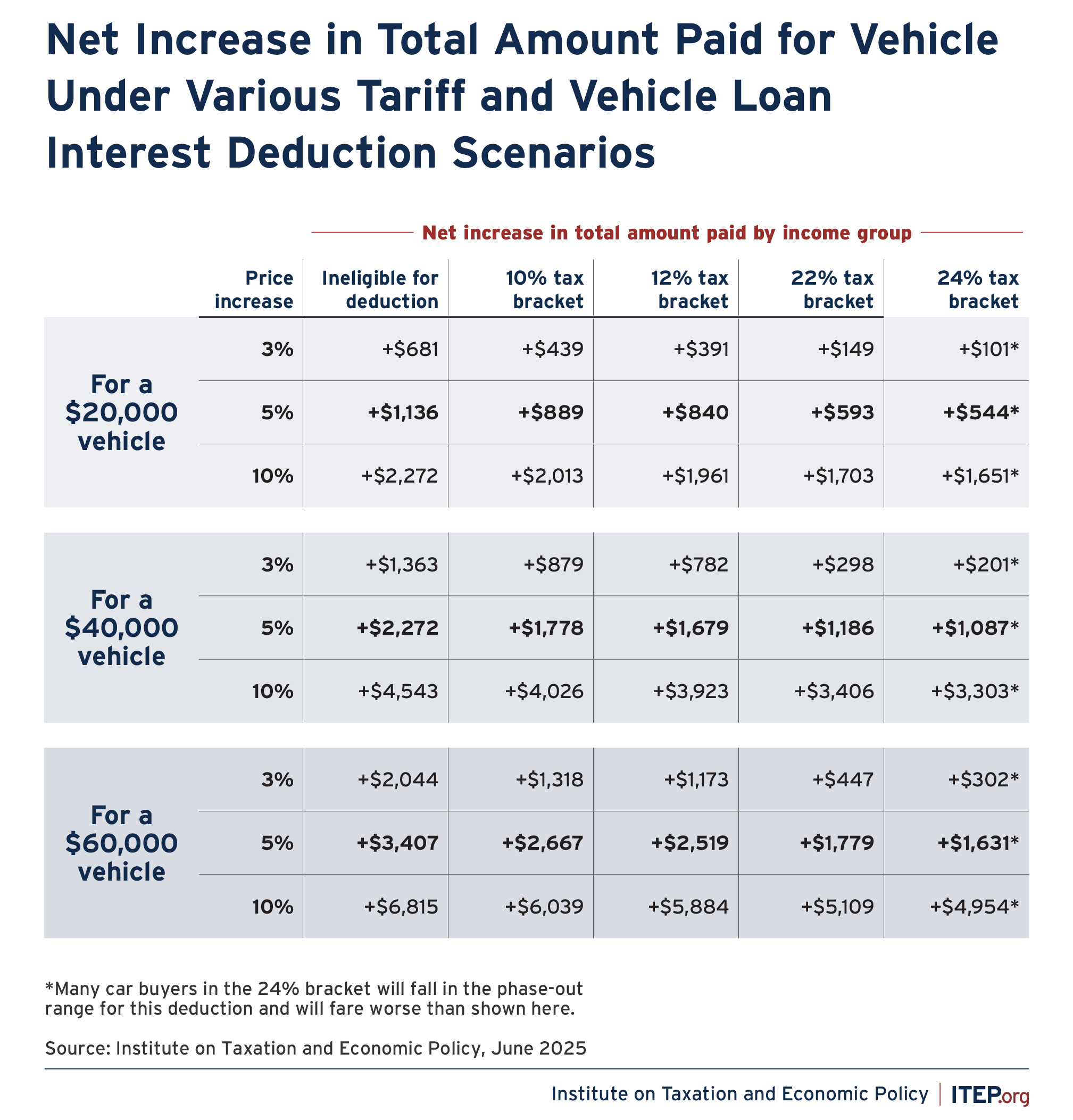

Figure 3 expands this analysis to examine a range of scenarios where buyers purchase American-assembled vehicles priced at $20,000, $40,000, or $60,000 before the tariffs took effect. Those ineligible for the deduction would face the highest price increases since they derive no benefit from the deduction. The next largest price increase would be for moderate-income buyers in the 10 percent tax bracket which for single filers applies to income of about $15,000 to $27,000 and for married filers to income of $30,000 to $54,000. At a tariff price increase of 5 percent, buyers in this bracket face price hikes about three-quarters the size of those who have no deduction benefit. In other words, their deduction only covers about a quarter of the price increase resulting from the tariffs.

Filers in the 24 percent bracket seem to fare the best, but this analysis presents a best-case scenario wherein the buyer isn’t affected by the phaseout of the deduction at high incomes. The phaseout range of $100,000 to $150,000 for single filers and $200,000 to $250,000 for married couples means many filers in the 24 percent bracket will have their interest deduction limited and will fare worse than indicated in this analysis.

“None of the scenarios examined here suggest that buyers of American-made cars would come out ahead from pairing tariffs of this magnitude with an auto loan interest deduction.”

The price increase scenarios of 3 and 10 percent show a similar pattern, with more of the tariff cost being offset for buyers in the higher tax brackets. And, though the deduction can offset a larger share of a 3 percent price increase relative to a 10 percent increase, none of the scenarios examined here suggest that buyers of American-made cars would come out ahead from pairing tariffs of this magnitude with an auto loan interest deduction.

FIGURE 3

Conclusion

The auto loan interest deduction that recently passed the House is designed, at least in part, to mitigate the impact of tariff-induced price increases on vehicles assembled in America. But the deduction is incapable of offsetting even small-scale price increases, especially for working-class families and others with moderate incomes.

Methodology

The calculations contained in this brief examine a range of scenarios that an individual car buyer could expect to confront under recent and proposed changes in U.S. tariff and tax policy. Different scenarios are examined based on the price of the vehicle being purchased, the degree to which that price is increased by higher tariffs, and the marginal tax rate against which the buyer claims a proposed tax deduction for vehicle loan interest payments.

The buyer in these examples is assumed to purchase a vehicle that qualifies for the temporary vehicle loan interest deduction contained in H.R. 1 of the 119th Congress, as passed by the House of Representatives on May 22. Among other things, final assembly of the vehicle must have occurred in the U.S. for it to qualify for the deduction.

The price effect of the tariffs will vary across vehicles, even for those assembled in America. This will occur both because American-assembled vehicles vary in the extent to which they contain foreign parts, and because the broader upheaval in prices caused by the tariffs will change consumer buying patterns in ways that will have varying effects on the level of demand for different types of vehicles.

Economists at Anderson Consulting Group have estimated that tariffs imposed by the Trump administration will raise the price of American-assembled vehicles by at least $2,000, with some models seeing higher increases of $10,000.[6] Industry group Cox Automotive estimates at least a 5 percent price increase in the total cost of vehicles assembled in the U.S.[7] These figures include the impact of a credit designed to temporarily blunt some of the tariff impact on American-assembled vehicles.

With these figures in mind, we use a 5 percent price increase as our base case scenario, with 3 and 10 percent increases presented to examine alternative degrees of potential price increases. Because we examine vehicles ranging from $20,000 to $60,000 in price before the tariffs are applied, this means we are examining price increases ranging from $600 to $6,000.

The car buyer examined in our analysis is assumed to have purchased their vehicle in October 2025. This slightly delayed purchase date was used in part because it will take time for automobile prices to adjust to reflect the higher costs associated with tariffs imposed in the spring. Fall is also a popular time for vehicle purchases as new model year vehicles start to become available. As explained below, the purchase date is also relevant to determining how many months of interest payments will be eligible for the temporary loan interest deduction.

The car buyer is assumed to make a fairly typical 20 percent down payment on their vehicle, and to finance the other 80 percent. That 80 percent is financed at an interest rate of 6.35 percent, in line with the average vehicle loan interest rate reported by Experian for the fourth quarter of 2024.[8] Because most of the vehicle purchase is financed, the higher sticker prices associated with tariffs are amplified somewhat by additional interest payments on the larger borrowed amount. This is why, for example, a 10 percent price increase for a $40,000 car costs the buyer who is ineligible for the deduction $4,543 rather than $4,000.

Most car loan terms are 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, or 84 months. The buyer in our examples is assumed to have selected a 60-month term, slightly below the 68-month average reported by Experian.[9] Our decision to use a loan term slightly below the average term causes us to slightly overstate the degree to which the loan interest deduction will offset the tariff effects for a typical buyer because it moves a larger share of the interest payments into the window of time (January 2025 to December 2028) when such interest would be deductible under H.R. 1. Under our examples, the buyer can deduct 39 of their 60 interest payments, with the final 21 payments occurring after the loan interest deduction in H.R. 1 has lapsed. It bears noting that buyers purchasing vehicles after our assumed October 2025 purchase date would be able to deduct fewer interest payments.

The value of those interest deductions will vary across taxpayers depending on their marginal tax rate and whether their income falls within the eligibility range for the program. Under H.R. 1, low-income taxpayers would see no benefit from the deduction if their taxable incomes are entirely offset by the standard deduction and other tax preferences, as they would face a 0 percent marginal tax rate. While low-income families are more likely to buy used cars, it bears noting that even used car prices are expected to rise as consumer demand increases for vehicles that were not subject to the tariffs.

High-income taxpayers would also see no benefit from the deduction because the deduction is unavailable to single taxpayers with incomes above $150,000 and married couples with incomes above $250,000.

A potentially reduced deduction is available to singles earning between $100,000 and $150,000 and to couples earning between $200,000 and $250,000. Specifically, the $10,000 cap on the amount of deductible interest is lowered by 20 cents for every dollar that income exceeds the phase-out starting points. A single person earning $145,000, for example, could only deduct up to $1,000 in vehicle loan interest per year. The bulk of taxpayers in the phase-out range for the deduction are likely to face a 24 percent marginal tax rate. The results for buyers in the 24 percent tax bracket presented in this report should therefore be interpreted cautiously as they are only valid for taxpayers not impacted by the phase-out and thus overstate the benefit of the deduction for any taxpayer who sees their interest deduction reduced by the phase-out.

Finally, it bears noting that this brief does not consider the impact of state-level tax policy effects on car buyers, as those effects would vary both in magnitude and direction across states. If some of the 41 states with personal income taxes respond to H.R. 1 by choosing to offer their own auto loan interest deductions, buyers living in those states would find that the ability to write-off such loan interest would be more impactful than shown here. On the other hand, the actual after-tax price increase resulting from the tariffs would be somewhat larger than shown here in the 45 states with sales taxes because those taxes would amplify the price increase. For example, in a state with a 5 percent sales tax, a 10 percent increase in pre-tax prices would amount to 10.5 percent after the sales tax is applied. Whether state tax policy would cause buyers to fare better or worse than depicted in this brief would vary across states depending on the particulars of their income and sales tax structures.

Endnotes

[1] Anderson Economic Group. “Tariff Costs for U.S.-Assembled Vehicles Drop Under ‘Adjusted’ Policy.” May 1, 2025. Available at: https://www.andersoneconomicgroup.com/tariffs-economic-impact-on-auto-industry/.

[2] Cox Automotive. “New Auto Tariffs Are Now in Place, Driving the Industry into Uncharted Territory.” April 4, 2025. Available at: https://www.coxautoinc.com/market-insights/new-auto-tariffs-are-now-in-place-driving-the-industry-into-uncharted-territory/.

[3] In March, Trump addressed Congress, “And I also want to make interest payments on car loans tax deductible, but only if the car is made in America. Oh, and by the way, we’re going to have growth in the auto industry like nobody’s ever seen. Plants are opening up all over the place. Deals are being made like never seen. That’s a combination of the election win and tariffs. It’s a beautiful word, isn’t it? That that along with our other policies will allow our auto industry to absolutely boom. It’s going to boom.” A transcript of the full March 4th speech is available via the Associated Press at: https://apnews.com/article/trump-speech-congress-transcript-751b5891a3265ff1e5c1409c391fef7c. In May, Michigan Representative Bill Huizenga, who sponsored the Made in America Motors Act which featured a similar interest deduction said, “Making interest on car loans tax deductible was a key campaign promise made by President Trump. The Made in America Motors Act delivers on this promise by giving individuals and families a financial incentive to buy American, which in turn supports good-paying automotive jobs in Michigan and across the nation.” Todd Spangler. “Michigan Rep. Huizenga proposes auto loan tax deduction for US-made cars to offset tariffs.” USA Today. May 7, 2025. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2025/05/07/huizenga-proposes-auto-loan-tax-deduction/83501536007/.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “The Impact of Trump’s Tariffs.” April 23, 2025. Available at: https://itep.org/trump-tariffs-tax-increase-impact/. Davis, Carl. “The House Tax Plan by the Numbers.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. May 16, 2025. Available at: https://itep.org/house-tax-plan-trump-tax-cuts-by-the-numbers/.

[5] See note 2.

[6] See note 1.

[7] See note 2.

[8] Ben Luthi. “Auto Loan Rates and Financing for 2025.” Experian. April 24, 2025. Available at: https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/auto-loan-rates-financing/.

[9] Axelton, Karen. “What’s the Average Length of a Car Loan?.” Experian. October 3, 2024. Available at: https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-the-average-length-of-a-car-loan/.