Key findings

● Every state with a personal income tax offers tax subsidies for seniors that are unavailable to younger taxpayers. The best academic research suggests that the median state asks senior citizens to pay about one-third less in personal income tax than younger families with similar incomes. The bulk of these subsidies are costly and poorly targeted. In many states, high-income seniors pay less tax than younger families with much lower incomes. And yet too many states have been on a steady march toward enacting and expanding carveouts for seniors.

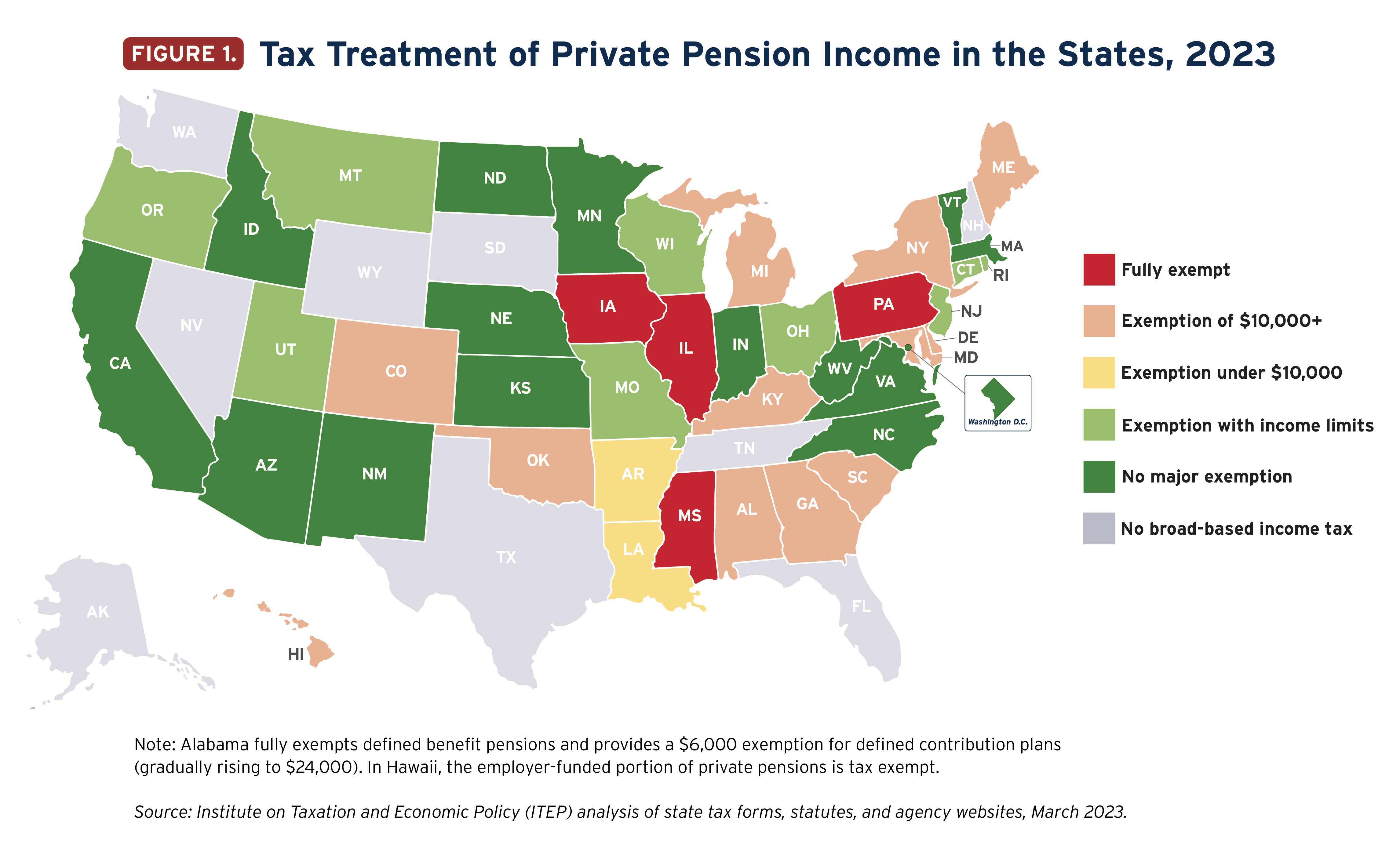

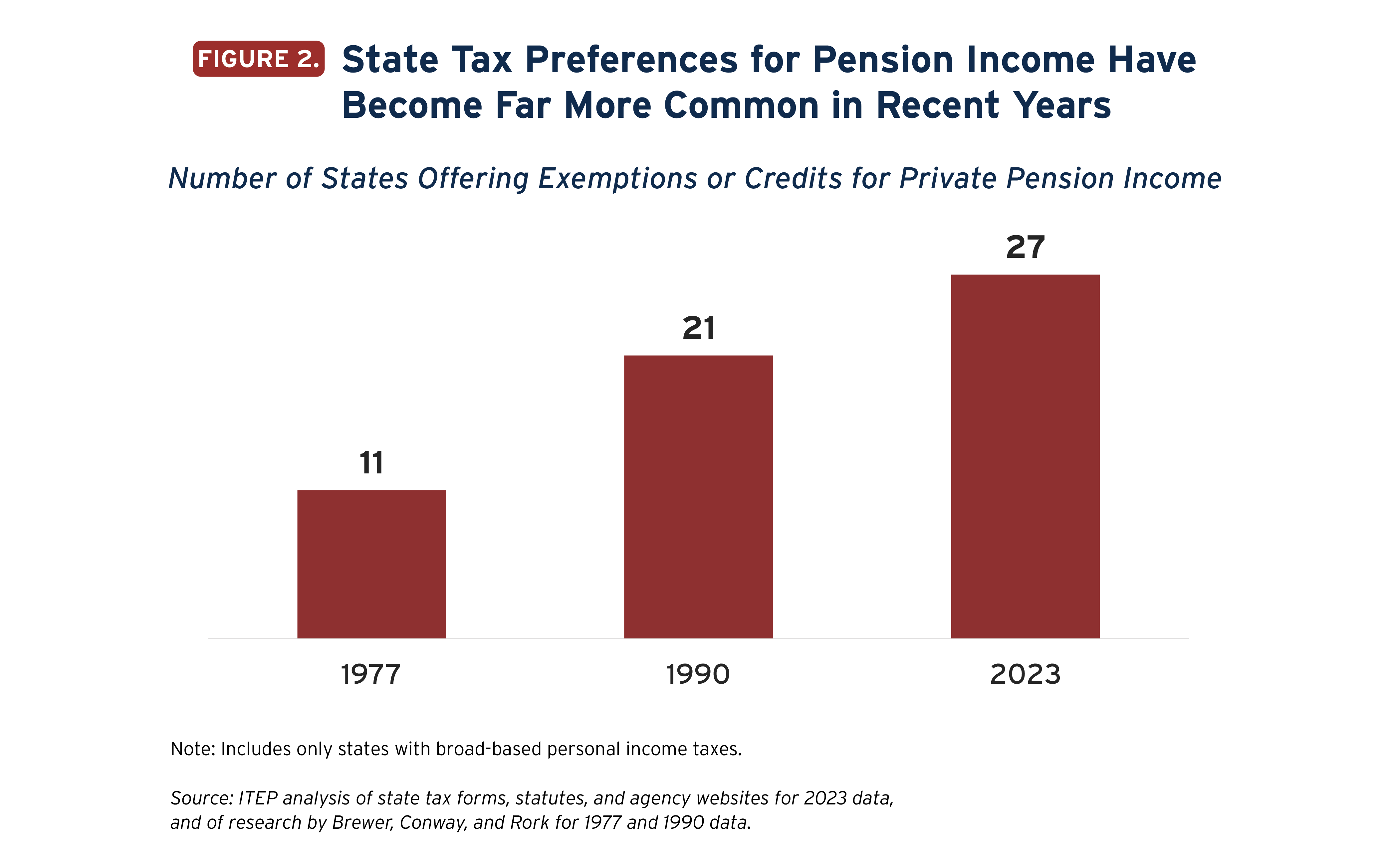

● Twenty-seven states offer an exemption or credit for private pension income in 2023, up from 21 states in 1990 and just 11 states in 1977. Every state provides a substantial income tax exemption for Social Security income as well, with 32 states choosing to exempt this income entirely, even for very wealthy families. Other types of tax subsidies targeted exclusively to older adults are common as well.

● We estimate that income tax subsidies for older adults are draining state personal income tax collections by roughly 9 percent, or $48 billion, in 2023. This substantial revenue loss makes it more difficult for states to invest in amenities like infrastructure that can greatly improve quality of life in retirement. It also stands in the way of ending chronic underinvestment in our nation’s young people with efforts to lower child poverty, expand preschool access, make college more affordable, and otherwise promote economic opportunity.

● Many of these subsidies disproportionately benefit the wealthy, worsen racial inequality, create generational inequities, and weaken states’ fiscal positions without offering any meaningful upside.

● Under a well-designed personal income tax based on ability to pay, it is not necessary to offer special tax subsidies to older adults that cannot be accessed by younger families. Families should be charged tax bills they can afford without age being a deciding factor. Moreover, because most states built their tax laws atop the federal system—which includes substantial senior tax subsidies such as a partial exemption for Social Security income, lavish subsidies for retirement savings, and a larger standard deduction—there is no need for them to add additional subsidies of their own.

● For states that insist on treating their older residents more favorably than young families, there are some options that are less problematic than others. Tax credits tend to be more equitable than exemptions, for instance. Income limits and phase-outs are also valuable tools for lessening the degree to which senior tax subsidies flow to families not in need of special treatment. The core purpose of retirement tax subsidies should be to protect the economic security of lower- and moderate-income seniors. Better policy design can help direct a larger share of any subsidy toward these populations.

State governments provide a wide array of tax subsidies to their older residents. Every state that levies an income tax allows some form of income tax exemption or credit for people over age 65 that is unavailable to younger taxpayers. Most states also provide special property tax subsidies to seniors. Too many of these carveouts focus on predominately wealthy and white seniors, all while the cost climbs. This report surveys federal and state approaches to reducing taxes for older adults and suggests options for designing less costly and better targeted tax preferences.

Seniors Receive Substantial Tax Subsidies at Both the Federal and State Levels

Federal Income Tax Subsidies

Federal tax law provides substantial tax subsidies to seniors. Partly because of these subsidies, roughly 8 in 10 people over the age of 75 do not pay federal personal income tax while the other 2 in 10 typically pay a lower tax bill than younger people earning similar incomes.[1] Federal income tax subsidies for seniors include:

● Retirement Savings Subsidies

Federal law authorizes several tax-preferred savings accounts such as defined benefit pension plans, 401(k) retirement plans, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), and Roth IRAs. These accounts are especially favorable to wealthy individuals and the upper-middle class.[2] Contributions to traditional pensions and IRAs are made with pre-tax dollars; no tax is owed until the funds are withdrawn. For Roth accounts, contributions are made with after-tax dollars, but the income generated in these accounts is fully tax-exempt when withdrawn after the age of 59 and a half. While most Roth account holders could reasonably be described as middle class, a significant number of very wealthy families also have substantial holdings in Roth IRAs.[3] Billionaire Peter Thiel, for example, was recently shown to be holding more than $5 billion in his Roth IRA.[4] Federal legislation signed in 2005 that allows high-income earners to circumvent income limits on Roth accounts will make this tax subsidy even less targeted over time.[5] Tax subsidies for these and other retirement savings accounts cost the federal government roughly $370 billion per year.[6] Viewed as a package, they represent the largest tax subsidy in federal law.

● A Partial Exemption for Social Security Benefits

No taxpayer with Social Security income pays tax on all their benefits. People with incomes below $25,000 ($32,000 for married couples) are fully exempt from paying taxes on Social Security benefits. (Income for this purpose is adjusted gross income plus half of Social Security benefits.) For people with incomes between $25,000 and $34,000 ($32,000 and $44,000 for married couples) up to 50 percent of benefits are taxable and for higher incomes up to 85 percent is subject to tax.

● A Larger Standard Deduction

Single people age 65 or older can claim an additional $1,850 on their standard deduction while those in married couples can claim an additional $1,500 for each spouse age 65 or older. This benefit is reasonably well targeted to middle-income seniors because high-income individuals and families are more likely to claim itemized deductions than the standard deduction.

State Income Tax Subsidies

Every state offers tax subsidies for seniors that are unavailable to younger taxpayers. These subsidies come in a wide variety of forms.

Under the property tax, for instance, many states provide larger homestead exemptions or tax credits for people aged 65 or older. Caps on property tax assessment growth also tend to be most valuable to older individuals who have seen their assessments artificially reduced for extended periods of time.[7]

Tax subsidies for older adults are also common in state income tax law. The median state asks senior households to pay about one-third less in state personal income tax than they would if they were headed by a younger taxpayer.[8] These subsidies take several different forms, as described below. Additional state detail on many of these policies can be found in Appendix B.

● Retirement Savings Subsidies

Nearly all states mirror the federal government’s policies related to retirement savings described above. This means, for instance, that contributions to 401(k) and similar retirement plans are generally made with pre-tax dollars. This arrangement primarily benefits upper-income seniors while doing comparatively little for lower-income earners who lack the means to set aside significant funds for retirement and who are in lower tax brackets where retirement savings tax exemptions are less beneficial. Moreover, income generated in Roth-style accounts is fully exempt from state income tax.

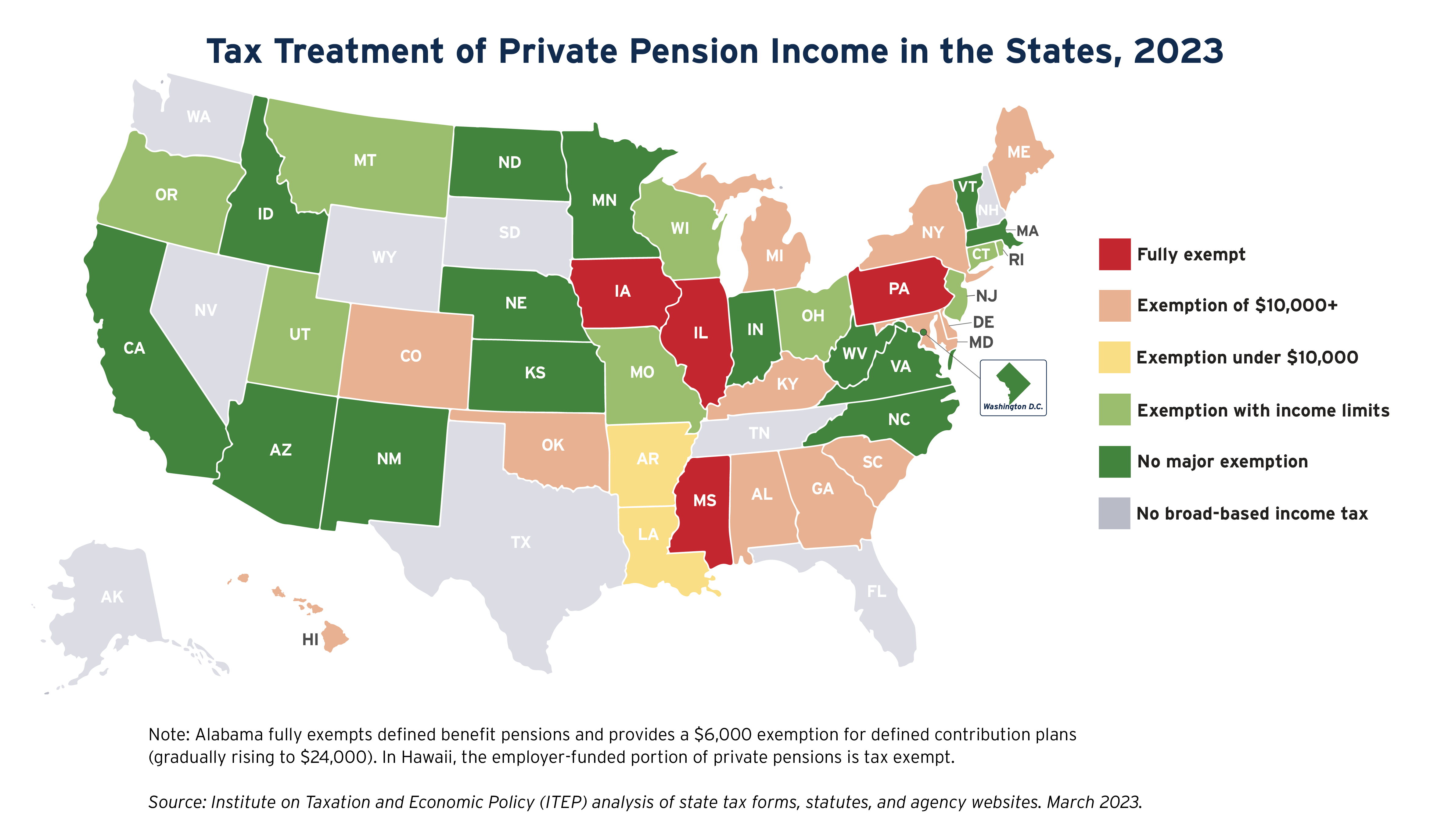

● Private Pension Benefits

Tax subsidies for private pension income, such as defined benefit plans or defined contribution 401(k)s, are among the costliest tax subsidies for seniors in state income tax law. Nearly every state exempts contributions to 401(k)s but some choose to exempt withdrawals as well—a decision that significantly compounds what is already a very large subsidy for these accounts.[9] Four states with a broad-based income tax (Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania) fully exempt such income from taxation. Eleven states generally tax private pensions in the same manner as other forms of income, such as salaries and wages. The other 23 states with income taxes offer a variety of partial exemptions for private pension income, including modest exemptions of less than $10,000 (two states), larger exemptions of $10,000 per person or more (12 states), or income-targeted exemptions that phase out as income rises (nine states).

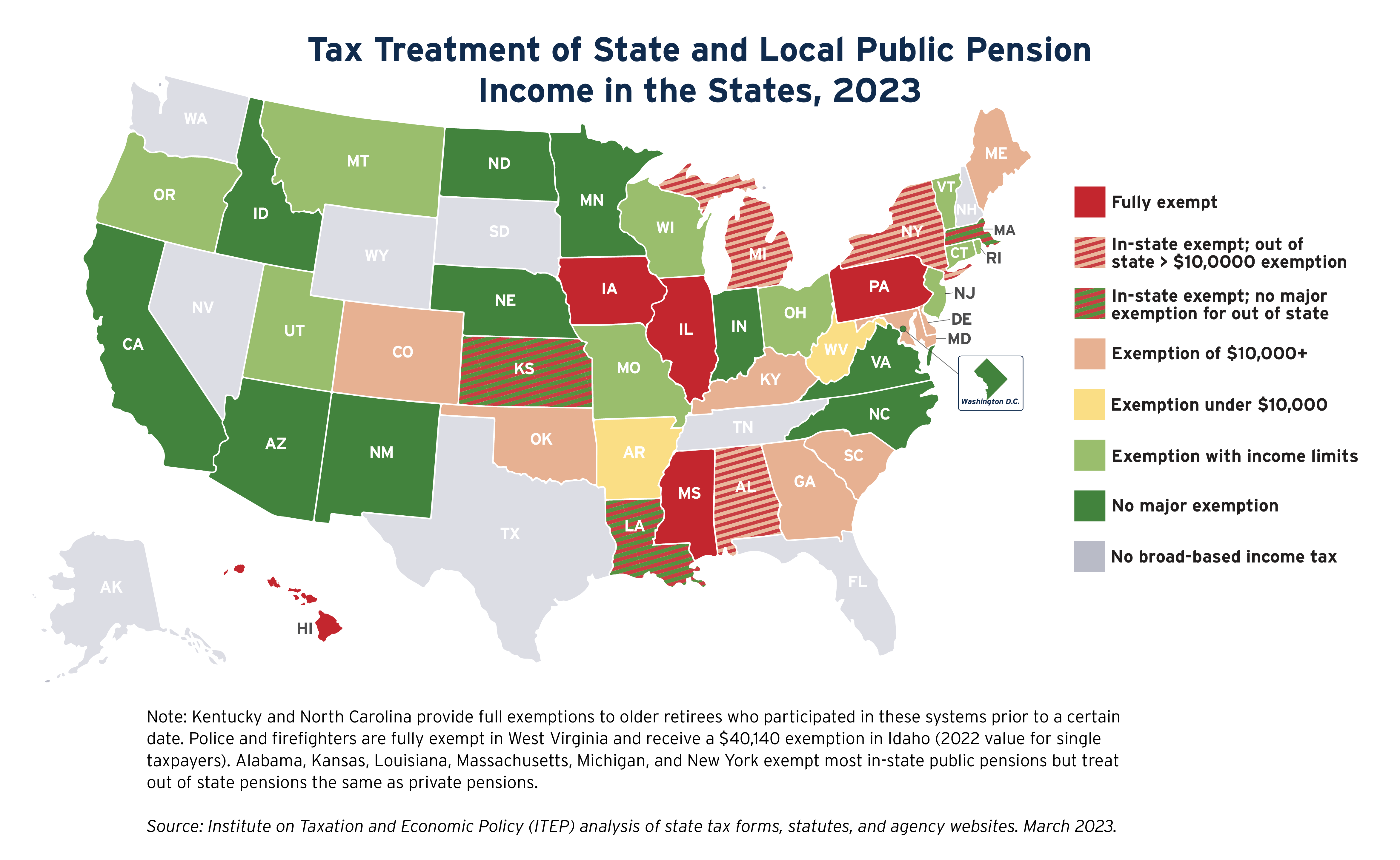

● Public Pension Benefits

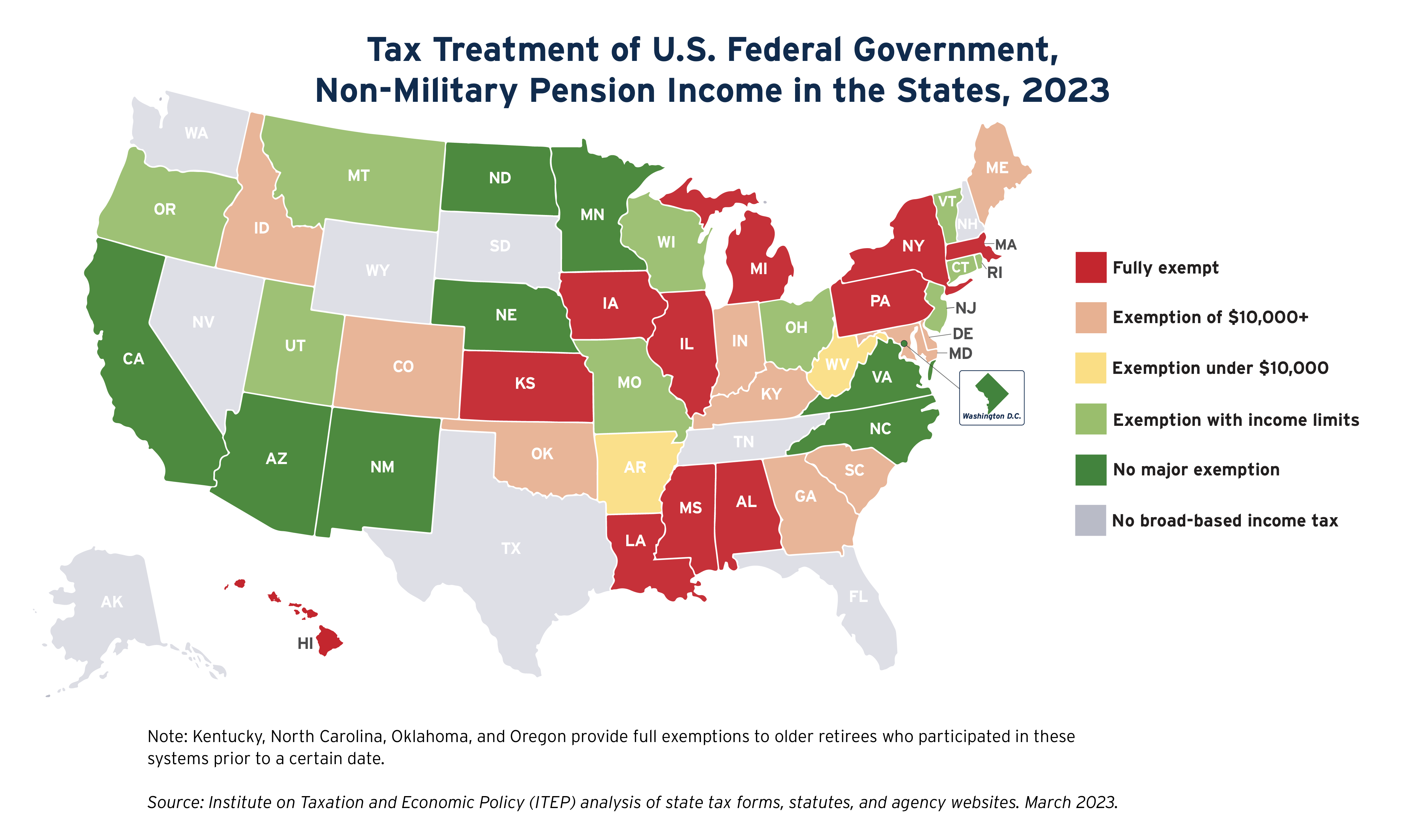

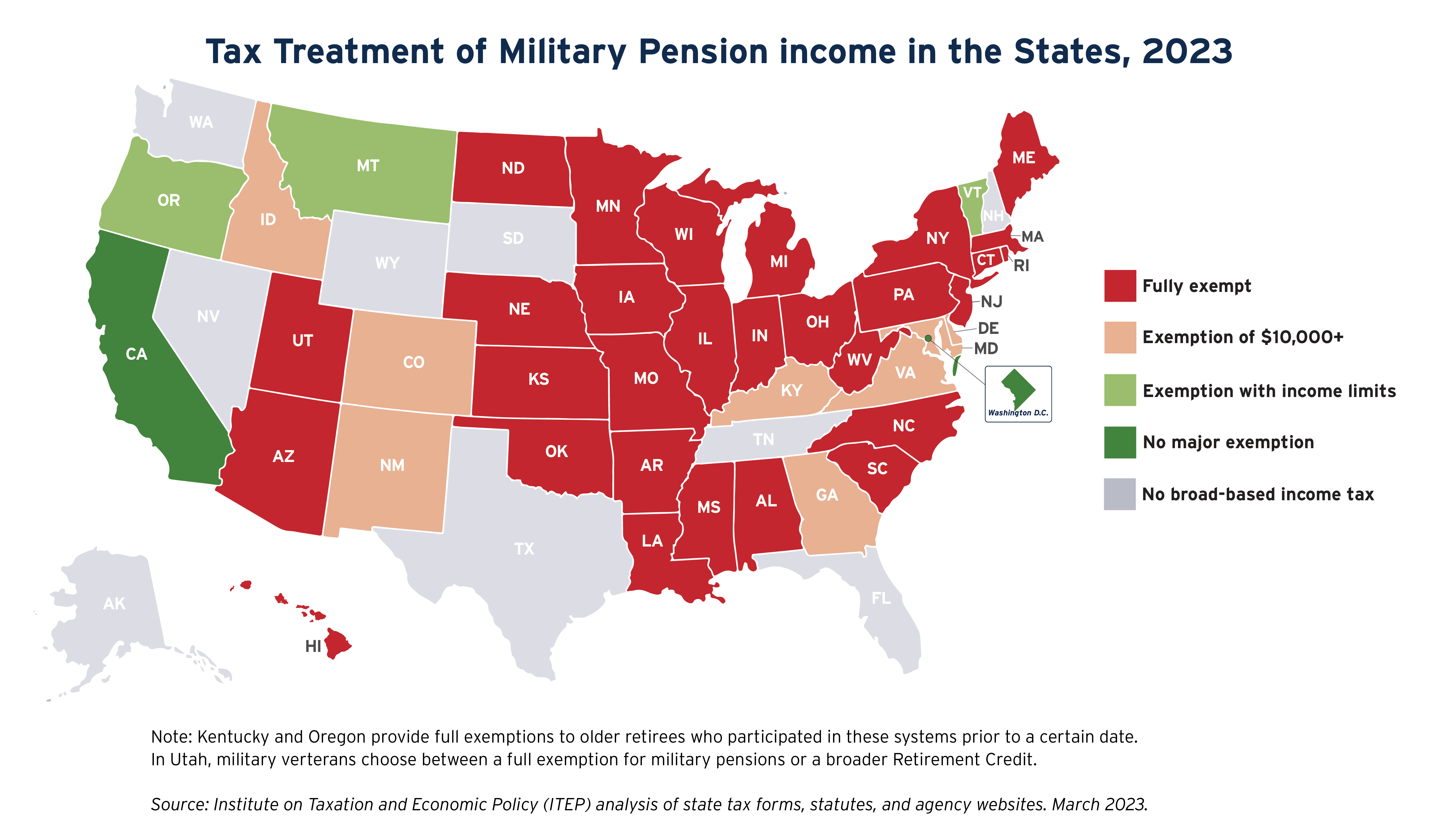

Public pension benefits are often treated differently depending on whether the plans are from employment with a state or local government, the federal government, or the military. Five states fully exempt state and local public pensions while another six states exempt pensions associated with their own state but not those of other states. Eleven states fully exempt federal government pension plans. Sometimes certain professions—such as police, firefighters, corrections officers, and park rangers—are rewarded with special tax subsidies unavailable to those who spent their careers in other lines of work. Military pension exemptions are the most common; 29 states offer these pensions a full exemption from tax.

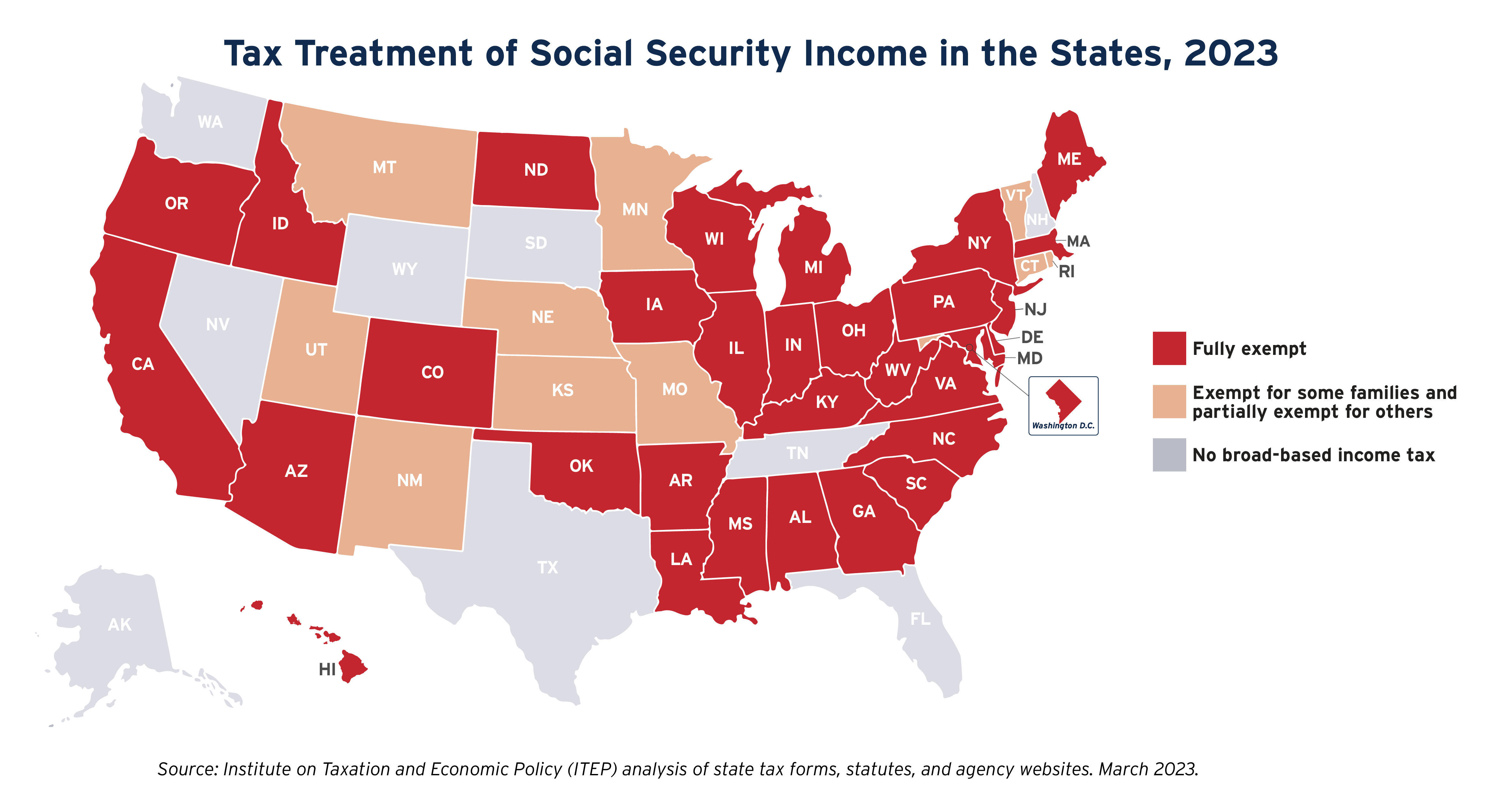

● Social Security

Thirty-two states with an income tax exempt all Social Security benefits from tax. The other 11 states exempt a portion of Social Security benefits. Most Social Security beneficiaries in these 11 states see their benefits fully exempted, with upper-income families paying tax on a portion of their benefits. In nearly all these 11 states, the partial exemptions being offered on Social Security income go beyond the exemption available in federal law.

● Other Income Tax Subsidies

Retirement tax subsidies are typically geared toward defined benefit pension plans and workplace retirement plans such as 401(k)s. But some states define income for purposes of these subsidies more broadly. Georgia, for instance, offers a sweeping retirement exemption that includes not just pensions but also IRAs, interest, dividends, capital gains, royalties, rental income, and up to $4,000 of earned income. Other states offer a larger personal exemption or standard deduction for taxpayers 65 and up, with the latter often being linked to federal standard deduction rules. Virginia has one of the largest general tax subsidies for older individuals, in the form of a $12,000 exemption claimable against all sources of income for adults 65 and older with annual income below $50,000 ($75,000 for married couples).

State Tax Subsidies in Context

The size and scope of state personal income tax subsidies for older adults have grown substantially in recent years. Twenty-seven states offer an exemption or credit for private pension income in 2023, up from 21 states in 1990 and just 11 states in 1977. Many states with subsidies for pension or other retirement income have also chosen to increase those in recent years. Two examples are Iowa, where legislation fully exempting a broad swath of retirement income was signed in 2022, and Michigan, where very large retirement income subsidies pared back over a decade ago were reinstated under legislation signed in 2023.

The best available evidence suggests that tax subsidies for older adults lowered state income tax collections by about 5 percent in 1990 and by 7 percent in 2013.[10] This number has almost surely risen since 2013 as the population has continued to age and states have expanded the tax subsidies they offer to older adults. We estimate that the revenue loss is likely closer to 9 percent today, which collectively translates to at least $48 billion in lost state personal income tax revenue annually.[11] Billions more are foregone through property tax subsidies and local income tax subsidies for senior citizens, as well as through state conformity to federal retirement savings subsidies that are excluded from this total.

Designing Senior Tax Subsidies

Under a well-designed personal income tax based on ability to pay, it is unnecessary to create special tax subsidies for older adults that cannot be accessed by younger families. This is even more apparent in states that conform to federal tax law in administering their income taxes, as significant preferences for Social Security income and retirement savings come embedded in those laws. That being said, for state lawmakers intent on giving even more preferential treatment to senior citizens, there are some design decisions that can lead to better policy outcomes:

● Exemption, deduction, or credit?

States can provide income tax subsidies through deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, or through credits, which provide a dollar-for-dollar reduction in tax liability. Deductions are usually worth much more to upper-income taxpayers, while credits provide a more equal benefit to taxpayers with varying levels of income.

● What types of income should be eligible for tax subsidies?

Many state income tax exemptions for seniors apply only to certain types of income, such as pension benefits. Special tax subsidies for pension benefits shift the cost of funding public services away from older adults who have retired onto younger, working taxpayers. They also tend to be of little benefit to lower-income seniors, for whom Social Security makes up the bulk of their income.[12] Even more problematic than pension tax subsidies, however, are preferences afforded to broad swaths of “retirement income” such as in Georgia, where a portion of seniors’ capital gains and dividends are exempt. Capital gains and dividends—especially those generated outside of traditional retirement accounts—overwhelmingly flow to wealthy families.[13]

● How large should the special subsidy be?

States that provide exemptions for seniors often limit the amount that can be deducted. Arkansas, for example, allows seniors to exempt the first $6,000 of pension benefits per person. Yet other states allow much higher caps on deductions: Michigan, for instance, exempts more than $56,000 per person. And four states (Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania) completely exempt all private pension benefits from income tax. Larger exemption amounts make these subsidies more favorable to upper-income families. The average pension received by households with at least one person aged 65 or older was just over $8,500 in 2017.[14] Imposing a low cap on exemptions for seniors helps to target the benefits to seniors most in need and lessens the negative impact of these policies on states’ ability to fund services used by senior citizens and younger families alike.

● Income limitations?

Given the high cost of sweeping tax breaks for older adults, some states have taken the sensible step of tailoring their exemptions to benefit lower-income seniors most likely to be facing financial difficulties. For example, Montana exempts up to $4,640 of pension income but the exemption is gradually reduced to zero for single taxpayers with incomes over $38,660.

● Refundable or nonrefundable credit?

A refundable income tax credit is one that is available even to those who owe little or no income tax. Refundability can be valuable to low-income seniors who pay a larger portion of their income in sales and property taxes than in income taxes. Idaho, for example, offers a tax credit designed to offset sales tax payments made on grocery purchases. While taxpayers of all ages can qualify for the credit, seniors are afforded a somewhat higher credit amount. Income-limited refundable credits are the best-targeted and least expensive way to lower taxes for seniors with few financial resources.

State Tax Subsidies for Seniors are Deeply Flawed

On the whole, state exemptions for seniors result in tax systems that are less fair and less capable of funding essential services and institutions that benefit seniors and younger families alike. Far too many senior tax subsidies flow to wealthy families and worsen both racial and generational inequities. States should take a hard look at reform or repeal.

Senior tax preferences often go to wealthy families who already have many advantages in the tax code

In many cases, wealthy seniors reap the biggest benefits from state income tax subsidies designed for older adults.

Low-income seniors are already shielded from income taxes on Social Security if states follow the federal rules. In states that choose to exempt all Social Security benefits, that additional subsidy is directed almost exclusively to those who clearly do not need it. A recent ITEP analysis of a proposal to fully exempt Social Security income from tax in Minnesota, for instance, found that more than half (58 percent) of the tax cuts associated with doing so would flow to households with incomes over $143,000.[15]

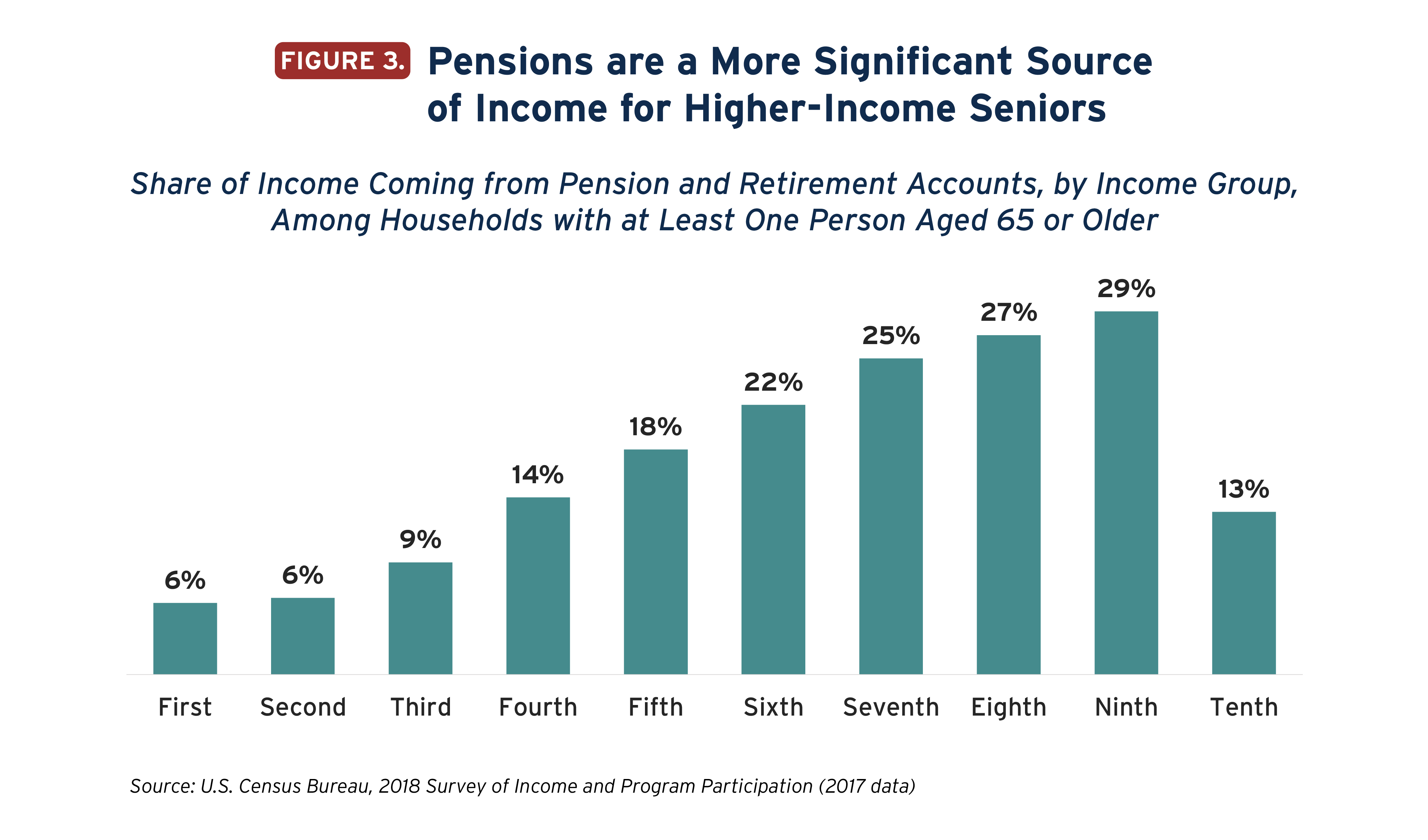

Pension tax subsidies are skewed in favor of wealthy seniors as well, since pension income is a more important source of income for higher-income seniors and the upper-middle class in particular.[16] Upper-income seniors often derive a quarter or more of their income from pensions and retirement accounts while the bottom third of seniors, by contrast, receive less than 10 percent of their income from these sources.

Our analysis of Illinois’s carveout for retirement income—including pensions and other retirement accounts—indicates a similar pattern. Using the ITEP microsimulation tax model we found that families in the 80th to 95th percentile, with average incomes of about $230,000 per year, tend to receive a larger tax cut relative to income than any other group. In total, almost 60 percent of Illinois’s retirement tax subsidy flows to people with incomes over $175,000. The distribution of that subsidy is even more skewed when looking at average dollar tax cuts as the top 1 percent of families by income see the largest cuts.[17]

The reality is that most seniors receiving tax benefits can afford their tax bills just fine. Rather than carve out large slices of the population from the tax base, lawmakers would be better served tailoring any tax benefits they wish to offer toward families facing economic insecurity regardless of their age.

Large and growing costs

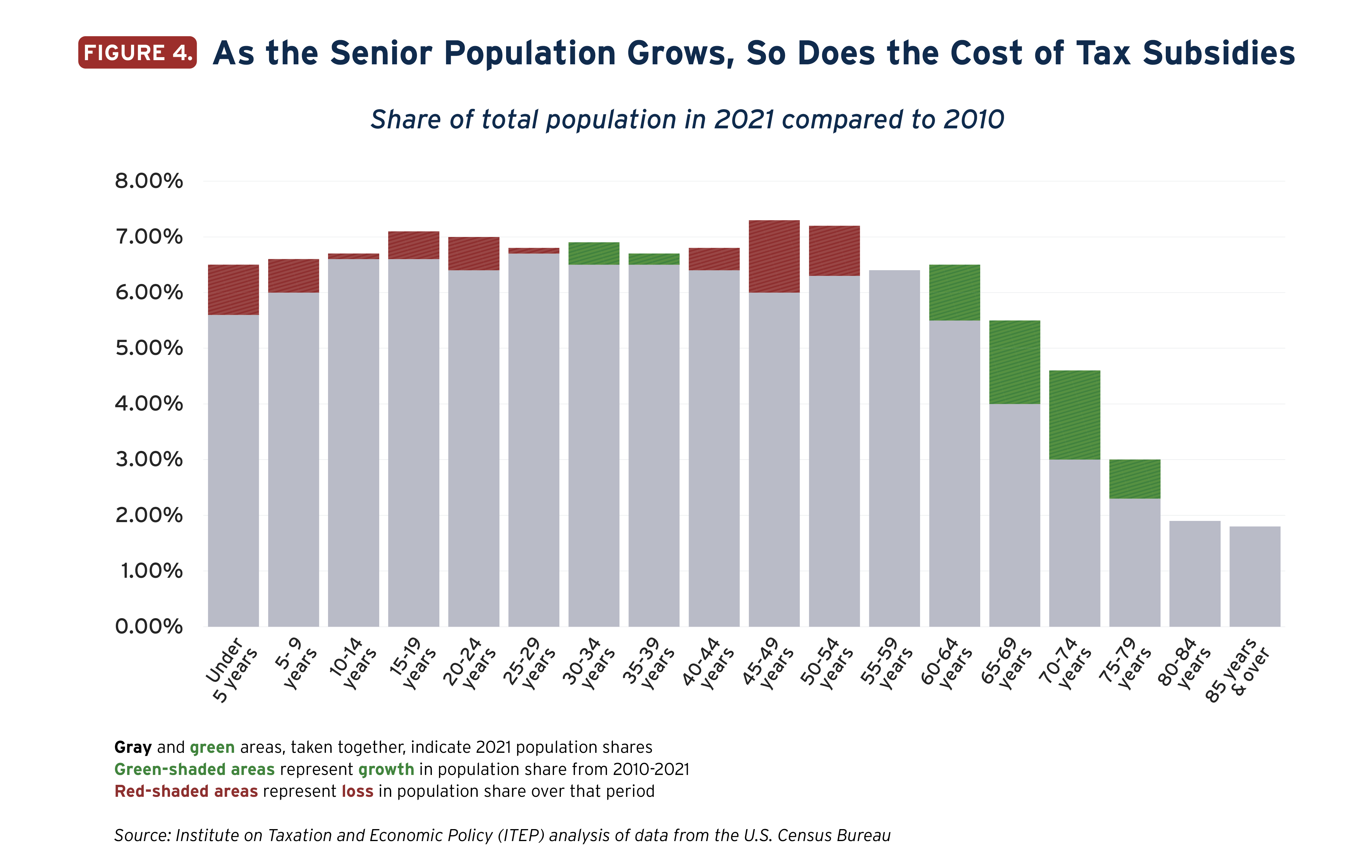

Poorly targeted tax subsidies for senior citizens are a costly commitment for states and long-term demographic changes threaten to make these subsidies increasingly unaffordable over time.

Analysis presented earlier in this report suggests that senior tax subsidies are reducing state personal income tax collections by about 9 percent, or $48 billion per year. As large as that figure is, it will likely grow further as the population continues to age unless lawmakers make needed changes.

Older adults are the fastest growing age demographic in the country. The population of adults 55 and older grew by 29.2 percent between 2010 and 2020, while the population of those under 55 grew only by 0.2 percent, according to the U.S. Census. This trend is even starker in some states, where rapid growth in the population of older adults is paired with population decline among those under age 55. (Data for each state can be found in Appendix A.)

The aging of the U.S. is happening in parallel with other major demographic changes and is not necessarily good or bad overall.[18] But over time, absent a major change in immigration policy this demographic shift will require a shrinking pool of workers to fund public services that an expanding pool of retirees will contribute comparatively little to, owing to substantial senior tax subsidies. This trend heightens the need to target these subsidies appropriately to minimize their cost.

Perhaps no state exemplifies the pitfalls better than Illinois. Much ink has been spilled over Illinois’ fiscal troubles. The state’s fiscal woes are more nuanced than some would claim and while tax subsidies for seniors are not their sole or even principal cause, exclusion of almost all retirement income from taxation has been exceptionally costly for the state.[19] The state’s exemptions for pension income will cost nearly $3 billion in 2023 alone, money that could have been spent on state services, pension obligations, or rebalancing for a fairer tax code. Given current population trends in the state, that cost will grow significantly in the years ahead.

Ultimately, the high cost of carving out senior citizens’ income from the tax base makes it far more difficult for states to provide robust services that improve residents’ quality of life and the economy. Much of that impact falls on children and young families in the form of larger class sizes, fewer preschool spots, or a lack of affordable options for attending college. But it also harms older people when states lack the resources to invest adequately in infrastructure, the safety net, environmental quality, and other areas.

Generational equity is hindered by many senior tax subsidies

Tax preferences for senior citizens raise questions of “horizontal equity.”[20] Why should an older person be treated drastically differently from someone younger if their positions are similar in most important respects?

While income tax laws vary across states, the median state asks senior citizens to pay about one-third less in personal income tax than younger families with equivalent incomes. In at least half a dozen states, seniors pay less than half as much income tax as comparable younger families.[21]

At low income levels, senior tax subsidies are often not the best means to aid seniors in precarious financial positions. If low-income seniors are finding their state personal income tax bills unaffordable, then younger low-income people are likely facing the same difficulties and lawmakers should consider broad tax reform, not special carveouts for senior citizens.

For high-income families, the case for providing special income tax treatment to seniors is exceptionally weak. The highest-income seniors in Georgia, for instance, pay just 63 percent of what their younger neighbors with similar incomes pay.[22] And many high-income seniors in places like Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania pay less income tax than young families with far lower incomes.

The frantic push toward larger tax subsidies for seniors that we are witnessing right now is violating an intergenerational compact. When people above a certain age are allowed to contribute far less to funding public services—even when they clearly have the means to do so—our shared investment and attachment to society is weakened. Older Americans grew up in a world with fewer state tax exemptions for pension income than we see today and benefited from the public services that tax contributions by their elders helped make possible, many of which, like affordable college, have been weakened.

As the Baby Boomer generation opens the door to a torrent of new pension tax subsidies, the younger, more diverse generations that follow will have to endure lower-quality services, higher taxes, or some combination of these outcomes as a result.

Moreover, by the time that retirement arrives for these younger generations there are no guarantees that the present suite of state tax benefits will even remain in place, given their immense and rising costs and exceptionally weak policy merits. While programs like Social Security and Medicare face some of the same fiscal pressures as state tax subsidies for seniors, these federal programs are fundamentally sound and immensely popular. When it comes to regressive state tax subsidies, on the other hand, it is less likely that future state leaders will indefinitely leave in place a system that requires younger people to pay more so that seniors can pay less.

Senior tax subsidies often worsen racial disparities

Historic and ongoing discrimination have created stark racial disparities in the U.S. across countless measures.[23] A significant share of the racial wealth gap is a direct result of white wealth accumulated under various subordinating legal regimes from chattel slavery to racialized property covenants. Unequal returns to white wealth relative to that held by people of color have played a huge role in carrying this gap through to the present day.[24] Tax policy can affect wealth inequality in important ways and, in many respects, state income tax subsidies for seniors are actively making this disparity worse.[25]

As discussed above, the Baby Boomer generation—far whiter than the generations following it—stands to benefit most from the rapid shift toward heavy tax preferences for older adults.[26] On top of that, the way in which state tax subsidies have been designed often adds to that inequity by steering much of their benefits to higher-income seniors, who are disproportionately white.

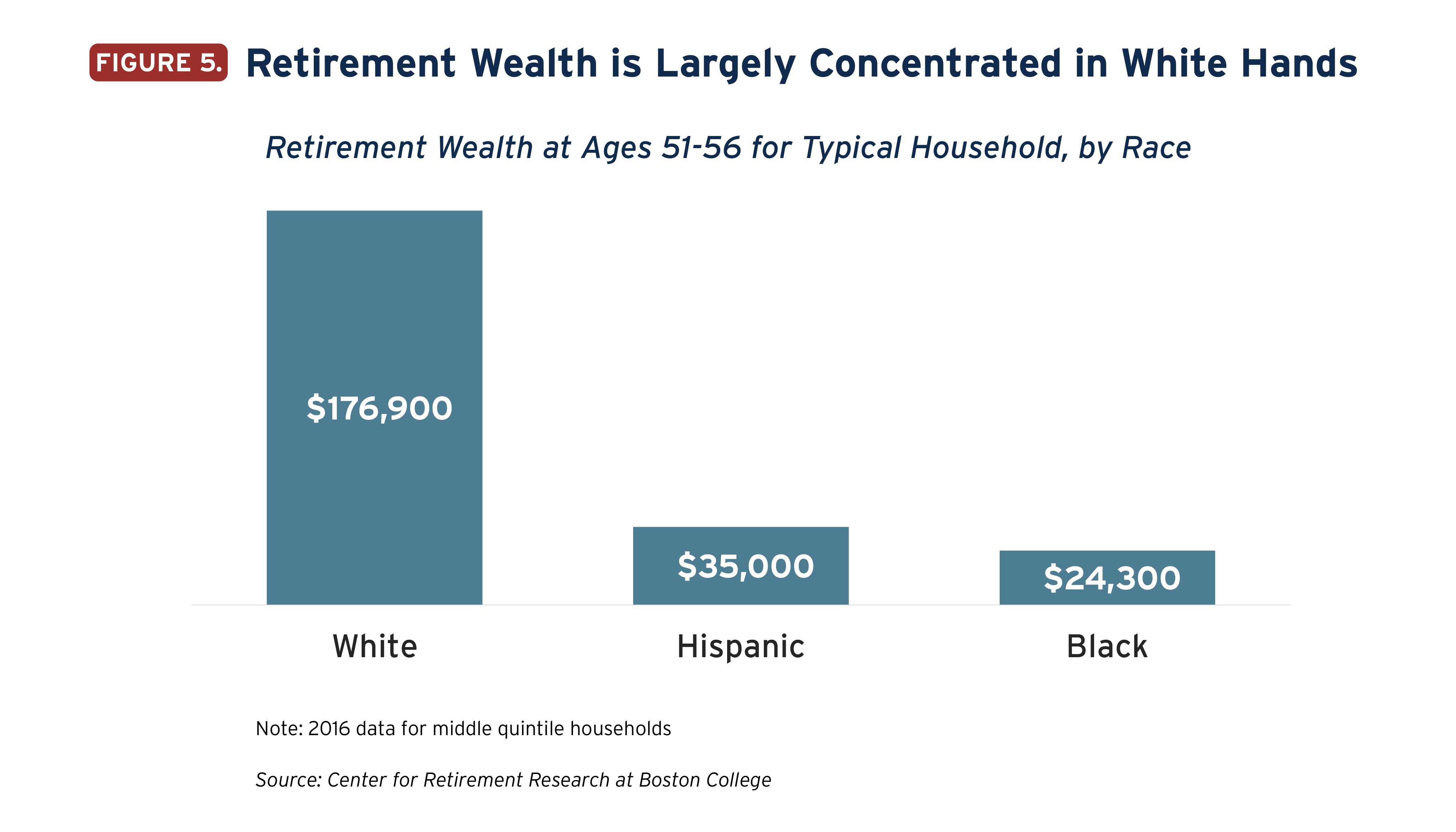

Pension tax subsidies in particular skew toward white households because of the immensely unequal distribution of retirement wealth. As middle-income households approach retirement age, the typical white family has roughly five times as much retirement wealth as Hispanic families and seven times as much as Black families.[27] These figures have changed relatively little in recent decades, indicating a high degree of entrenched retirement wealth inequality that pension tax subsidies tend to solidify.

Partly this is a result of lower earnings among Black and Hispanic families who have faced persistent discrimination in the labor market and other areas. But wealth inequality is also a generational issue. On average, people of color have families and communities with less wealth than white communities. As a result, even high earners devote more of their earnings to supporting others and are less likely to receive inheritances.[28] At any given income level, then, people of color tend to have fewer financial resources left over to set aside in retirement savings plans.

The racial wealth gap is a daunting problem that will not be solved through any one single approach. This makes it all the more important that the tax code contributes to a solution. Narrowing these gaps should be a major policy goal. States cannot afford to have tax policies in place that make the problem worse.

Tax policies do not drive senior migration

Some lawmakers attempt to justify tax subsidies for seniors by saying they will help stop out-migration or encourage in-migration. But the evidence in support of tax-induced migration is generally weak.[29] Scholars do not tend to view taxes as a particularly important aspect of migration: one recent summary paper on the economics of internal migration included almost no substantive discussion of taxation, for instance.[30] Another study focused on senior tax subsidies noted that “elderly migration is a fairly rare event” and was able to find “no consistent evidence that these tax breaks influence migration decision in a meaningful way.”[31]

Given how rarely seniors relocate across state borders, the vast majority of senior tax subsidies are inevitably a windfall to people who would have been living in the state anyway, rather than a genuine behavior-shaping incentive. Instead of participating in a race to the bottom in setting senior tax rates, states interested in doing well by their senior populations would be far better off focusing on quality-of-life issues, health care access, and housing costs—all factors that cannot be advanced in a meaningful way with income tax carveouts.

Recommendations

Federal law provides extremely lucrative tax subsidies to senior citizens through tax-preferred retirement accounts and a generous exemption for Social Security income. States with income taxes not only mimic these subsidies in their own tax codes, but also go well beyond them by offering additional layers of subsidies that are often poorly targeted and extremely costly.

Under a well-designed state income tax where tax liability is based on ability to pay, there is no need to offer additional tax subsidies to senior citizens beyond those available to younger individuals and families. Low-income seniors can be exempted from state income tax through broad-based deductions and credits available to people of all ages, while middle-income seniors should pay some tax just like other middle-income families and high-income seniors should pay more substantial tax bills.

For states that insist on treating their older residents more favorably than young families, there are some options that are less problematic than others. Flat dollar tax credits, for example, are more equitable than exemptions that reduce taxable income because exemptions are more valuable when the income reduced is in the top brackets. Plus, exemptions are useless to economically vulnerable families who may not have income tax liability, but who pay substantial sales, excise, and other taxes. Credits offer the most level playing field.

Income limits and phase-outs set at reasonable levels are also valuable tools for lessening the degree to which senior tax subsidies flow to families who are not in need of special treatment.

Overall, the core purpose of retirement tax subsidies should be to protect the economic security of middle class and lower-income seniors. Better policy design can help to direct a larger share of any subsidy toward these populations.

Conclusion

Few demographic groups receive more attention from state lawmakers than senior citizens. Older Americans often have the money and time to engage in state and local politics with vigor, a fact that helps to explain the current landscape of senior tax subsidies. But political expediency does not always make for good policy.

State income tax subsidies for seniors typically grant the lion’s share of their benefits to the highest-earning seniors, worsen racial disparities, drive generational inequities, and significantly worsen states’ fiscal positions. These poorly targeted subsidies shift the cost of funding public services towards younger people, many of whom are less wealthy than the seniors benefiting from the tax breaks. Their high fiscal cost also makes it more difficult for states to invest adequately in public services and institutions that benefit young and old alike.

In truth, there is little need for states to pursue special carveouts for senior citizens. Well-designed income tax laws should already be based on ability to pay regardless of age. Even for states that fall short of that ideal, however, retooling tax subsidies to better target the neediest seniors and be more affordable will help states achieve fairer and more sustainable tax systems.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Endnotes

[1] Fullerton, Don, and Nirupama S. Rao. “The Lifecycle of the 47%.” National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22580/w22580.pdf.

[2] Wamhoff, Steve. “When Tax Breaks for Retirement Savings Enrich the Already Rich.” ITEP, 25 June 2021, https://itep.org/when-tax-breaks-for-retirement-savings-enrich-the-already-rich/.

[3] Barthold, T (2021). ‘Revenue Estimate.’ Joint Committee on Taxation Memorandum to Kara Getz, Tiffany Smith, and Drew Crouch. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/7.28.21%20JCT%20Mega%20IRA%20Data1.pdf.

[4] Elliott, J., P. Callahan, and J. Bandler (2021). ‘Lord of the Roths: How Tech Mogul Peter Thiel Turned a Retirement Account for the Middle Class Into a $5 Billion Tax-Free Piggy Bank.’ Pro Publica. June 24.

[5] The Tax Increase and Prevention Reconciliation Act (TIPRA) of 2005 facilitated so-called backdoor Roth IRAs, effective starting in 2010.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates of the cost of net exclusion of pension contributions and earnings from Keogh plans, defined benefit plans, and defined contribution plans plus the cost of both traditional and Roth IRAs.

[7] “Capping Property Taxes: A Primer.” ITEP, 1 Sept. 2011, https://itep.org/capping-property-taxes-a-primer/.

[8] McNichol, Elizabeth C. States Should Target Senior Tax Breaks Only to Those Need Them, Free up Funds for Investments. CBPP, 19 June 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-19-19sfp.pdf.

[9] Pennsylvania is a rare exception of a state that taxes contributions to 401(k) plans, but it also goes farther than almost any other state in exempting withdrawals from those plans.

[10] Brewer, Ben, Karen Smith Conway, and Jonathan C. Rork, “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform? State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly—Then and Now,” Public Finance Review 45(4), 564-594, 2017.

[11] Our analysis of U.S. Census data suggests that the share of the population aged 65 and older grew by roughly 30 percent between 2013 and 2023. Moreover, Social Security and taxable pension benefits expressed as a share of federal adjusted gross income grew by a very similar 31 percent between 2013 and 2020 (the most recent year with available data). With these two datapoints in mind, we use an adjustment factor of 30 percent to update Brewer, Conway, and Rork’s estimate that senior tax subsidies lowered state personal income tax collections by 7.02 percent in 2013. Making this adjustment suggests a revenue loss of 9 percent of state personal income tax revenue in 2023 and multiplying this by expected state personal income tax collections in 2023 yields a $48 billion revenue loss. This should provide a reasonable yet conservative estimate of the true revenue loss as it does not take into account legislation expanding state senior tax subsidies since 2013 and does not include all forms of state tax subsidies for senior citizens such as property tax programs, local income tax subsidies, and certain subsidies embedded more deeply in state law through conformity to the federal tax code, such as the exemption for income generated in Roth accounts.

[12] Thompson, Daniel, and Michael D. King. Income Sources of Older Households: 2017. U.S. Census, Feb. 2022, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p70br-177.pdf.

[13] Guzman, Marco. “State Taxation of Capital Gains: The Folly of Tax Cuts & Case for Proactive Reforms.” ITEP, 25 Sept. 2020, https://itep.org/state-taxation-of-capital-gains-the-folly-of-tax-cuts-case-for-proactive-reforms/.

[14] (Thompson & King)

[15] Minnesota Budget Project, “Tax cuts from unlimited Social Security exemption skewed to higher-income Minnesotans,” February 2023. https://www.mnbudgetproject.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/tax-cuts-from-full-social-security-exemption-skewed-to-higher-income-minnesotans-(pdf).pdf?sfvrsn=d989bbf4_6.

[16] Conway, Karen. “Senior Tax Breaks on the Move—but Are Seniors Actually Moving?” University of New Hampshire Casey School of Public Policy, 9 May 2017, https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/senior-tax-breaks.

[17] A description of the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model can be found online at: https://itep.org/itep-tax-model/.

[18] Frey, William H. Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America. Brookings Institution Press, 2015.

[19] Bruno, Robert, et al. “A ‘Pension Crisis’ Mentality Won’t Help: Thinking Differently About Illinois’ Retirement Systems.” UIC Government Finance Research Center, 19 Feb. 2019, https://uofi.app.box.com/s/gmtq4ydc5j8xz8ipwj1mpyg90j1vgkqh.

[20] “Tax Principles: Building Blocks of A Sound Tax System.” ITEP, 1 Dec. 2012, https://itep.org/tax-principles-building-block-of-a-sound-tax-system/.

[21] McNichol, Elizabeth C. States Should Target Senior Tax Breaks Only to Those Need Them, Free up Funds for Investments. CBPP, 19 June 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-19-19sfp.pdf.

[22] Brewer, Ben, et al. “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform? State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly—Then and Now.” Public Finance Review, vol. 45, no. 4, 2017, pp. 564–94, https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142116665903.

[23] Congressional Budget Office, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-02/58305-Wealth.pdf. Baradaran, Mehrsa. The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017. Karmecheva, Nadia, and Victoria Perez-Zetune. “Defined Benefit and Defined Contribution Plans and the Distribution of Family Wealth.”

[24] Perry, Andre, et al. “The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods.” Brookings, 27 Nov. 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/. Samms, Brakeyshia and Joe Hughes. “How the Inflation Reduction Act’s Tax Reforms Can Help Close the Racial Wealth Gap.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 20 Sep. 2022. https://itep.org/how-the-inflation-reduction-acts-tax-reforms-can-help-close-the-racial-wealth-gap/.

[25] Sanders, Courtney. “States’ Senior Tax Breaks Reinforce Unequal Wealth, Income by Race.” CBPP, 1 Aug. 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-senior-tax-breaks-reinforce-unequal-wealth-income-by-race.

[26] The Generation Gap in American Politics. Pew Research Center, 1 Mar. 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/03/01/the-generation-gap-in-american-politics/.

[27] Hou, Wenliang and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, “Social Security is a Great Equalizer,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. January 2020. https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/IB_20-2.pdf.

[28] Brown, Dorothy A., “The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans— And How We Can Fix It.” New York, Crown, 2021.

[29] Mazerov, Michael. “State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’

Interstate Moves.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 21 May 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-taxes-have-a-negligible-impact-on-americans-interstate-moves. Mazerov, Michael. “Tax-Related Migration Is Grossly Exaggerated: A Research Preview.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 10 Jan. 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/tax-related-migration-is-grossly-exaggerated-a-research-preview.

[30] Jia, Ning, Raven Molloy, Christopher Smith, and Abigail Wozniak (2022). “The Economics of Internal Migration: Advances and Policy Questions,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-003. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2022.003.

[31] Conway, Karen. “Senior Tax Breaks on the Move—but Are Seniors Actually Moving?” University of New Hampshire Casey School of Public Policy, 9 May 2017, https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/senior-tax-breaks.