Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

State lawmakers seeking to enact residential property tax relief have two broad options: across-the-board tax cuts for taxpayers at all income levels, and targeted tax breaks. More than 40 states have chosen to achieve across-the-board tax relief by providing a “homestead exemption.” This policy brief explains the workings of the homestead exemption and evaluates its strengths and weaknesses as a property tax relief strategy.

The Problem: Property Taxes Are Regressive

Residential property taxes are regressive, requiring low-income taxpayers to pay more of their income in taxes than wealthier taxpayers. ITEP found in its “Who Pays?: A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems of All 50 States” report that nationwide, the poorest twenty percent of Americans paid 3.6 percent of their income in residential property taxes, compared to 2.7 percent of income for middle-income taxpayers and 0.7 percent for the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans. The main reason property taxes are regressive is that home values are much higher as a share of income for low-income families than for the wealthy. Because property taxes are based on home values rather than income, property taxes are disconnected from “ability to pay” considerations in a way that income taxes are not: a taxpayer who suddenly becomes unemployed will find that her property tax bill is unchanged, even though her ability to pay it has fallen.

Homestead Exemptions: How They Work

Homestead Exemptions: How They Work

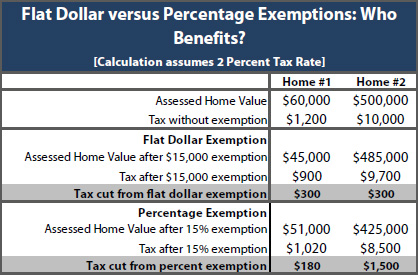

Homestead exemptions reduce property taxes for all homeowners by sheltering a certain amount of a home’s value from tax. Homestead exemptions are a progressive approach to property tax relief—that is, the largest tax cuts as a share of income go to lower- and middle income taxpayers. There are two broad types of homestead exemptions: flat dollar and percentage exemptions. Flat dollar exemptions are calculated by exempting a specified dollar amount from the value of a home before a tax rate is applied. These exemptions are especially beneficial to low-income homeowners, because they represent a larger share of property taxes (and of income) for low-income taxpayers. Percentage exemptions provide the same percentage tax cut to homeowners at all income levels. This form of exemption is also progressive, since an across-the-board cut in a regressive tax will be most helpful to low-income taxpayers—but it is far less effective at targeting relief to poor taxpayers than are flat exemptions.

The table on below illustrates this point using two examples. If a state allows a flat exemption for the first $15,000 of home value for all properties, that $15,000 exemption will result in a $300 tax cut for all homeowners in a given taxing district —regardless of whether their home is worth $60,000 or $500,000. By contrast, if the state allows a 15 percent exemption, a home worth $60,000 will receive a tax cut of just $180, while the half million dollar home will see a tax cut of $1,500.

Who Should Be Eligible?

Homestead exemptions provide “across the board” tax breaks—but these exemptions are not always available to the low-income renters who often need property tax relief most. At the other end of the spectrum, a few states have sensibly attached income limits to these exemptions. This ensures that the exemption will not be given to the very wealthiest taxpayers, and helps reduce their cost. The following three points should be kept in mind when thinking about the populations that benefit from homestead exemptions:

- Exemptions provide no benefit to taxpayers who rent their homes—even though it is accepted that property taxes on rental properties are partially passed through to renters. While expanding homestead exemptions to include rental properties would be administratively difficult, lawmakers should recognize this fact and consider enacting a property tax “circuit breaker” to accompany any relief provided via a homestead exemption. (See ITEP Brief, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers” for more information.)

- Many states also treat non-elderly taxpayers less generously than the elderly. Some states offer homestead exemptions only to elderly residents, while others give higher benefits to the elderly. The desire to extend property tax relief to elderly taxpayers is laudable, since the elderly are more likely to be “property rich” and “cash poor.” But low-income non-elderly taxpayers struggle with regressive property taxes in much the same way as their older neighbors.

- One sensible limitation on homestead exemptions actually helps to target these tax breaks: the use of income limits. Several states restrict eligibility for the exemption to taxpayers earning less than a specific income level or homes worth less than a set amount. In New York, for example, elderly homeowners can receive a bonus homestead exemption if their income is below roughly $80,000.

State-Financed and Locally Financed Exemptions: Who Foots the Bill?

Property taxes are usually collected by local governments, but homestead exemptions tend to be mandated by state law. State lawmakers creating a homestead exemption must decide whether to provide state funding to reimburse local governments for the cost of the exemption, or whether to force local governments to shoulder the cost. One advantage of a state-funded exemption is that it reduces pressure on local tax revenues, which can be unevenly distributed between poor and wealthy taxing districts. Locally-financed homestead exemptions force local governments to increase property tax rates on the remaining tax base, and do nothing to address the often-severe inequities of property tax wealth between districts.

Exemptions Can Lose Their Value Over Time

Fixed dollar exemptions tend to become less valuable over time. When housing values boomed in the early 2000’s, for example, most states’ fixed dollar homestead exemptions remained unchanged. As a result, homeowners saw their exemptions cover an increasingly small portion of their home value, and saw their tax bills rise as a result. Indexing exemptions (that is, automatically increasing the exemption every year to take account of inflation) can avoid this unintentional tax hike. (See ITEP Brief, “Indexing Income Taxes for Inflation: Why It Matters” for more information.)

A More Targeted Option: Low Income Credits

Homestead exemptions are a progressive approach to property tax relief. A modest, broad-based, flat dollar homestead exemption available to homeowners of all ages can significantly improve a state’s property tax system. But homestead exemptions also have two important flaws. First, they exclude renters, who tend to have lower incomes. Second, exemptions usually are given to homeowners at all income levels. This makes them an especially costly form of tax relief. The high cost of funding exemptions can make it harder for governments to balance budgets—and may force lawmakers to shift property taxes to other taxpayers, including businesses and renters.

Low-income credits are a relatively inexpensive alternative to homestead exemptions. For example, “circuit breaker” credits are targeted only to low-income taxpayers with exceptionally high property taxes. Unlike homestead exemptions, circuit breakers usually must be applied for—which means that some eligible taxpayers may not receive the benefits of a circuit breaker. But the ability to target these credits to whichever income groups are deemed most in need makes them much less costly than general homestead exemptions.