Sales taxes are one of the most important revenue sources for state and local governments; however, they are also among the most unfair taxes, falling more heavily on low- and middle-income households. Therefore, it is important that policymakers nationwide find ways to make sales taxes more equitable while preserving this important source of funding for public services. This policy brief discusses two approaches to a less regressive sales tax: broad-based exemptions and targeted sales tax credits.

Sales Taxes Disproportionately Impact Low- and Middle-Income Taxpayers

State and local sales taxes are inherently regressive, requiring a higher contribution as a share of income from low- and middle-income taxpayers than the wealthy, because lower-income families have no choice but to spend more of their income on items subject to the tax. To calculate a sales tax on a taxable item, the cost of the item is multiplied by the tax rate. For example, in Michigan, where the state sales tax rate is six percent, the direct sales tax on a $10 book is sixty cents. Taxpayers also often pay an indirect tax that is passed on from businesses to the consumer in the form of higher prices. So, in this case, both the state’s six percent tax rate and any business pass-through taxes (accounted for in the cost of the $10 book) are paid by everyone, regardless of their income.

According to Consumer Expenditure Survey data, ITEP estimates that low-income families typically spend three-quarters of their income on sales-taxable items, while middle-income families spend about half, and upper-income families spend roughly one sixth. This creates a stark imbalance, but lawmakers have multiple policy options at hand to provide relief for low-income taxpayers. They can provide:

- General sales tax exemptions for items that constitute a larger share of income for lower-income taxpayers, such as groceries and utilities.

- Targeted and refundable low-income tax credits in place of broad-based exemptions.

Exemptions and Credits: How They Work

Exemptions

Exemptions are the most popular approach to reducing the regressivity of the sales tax. In practice, they eliminate sales taxes on particular retail items. If exemptions are targeted to exclude items that make up an especially large share of low- and moderate-income households’ budgets they can, in turn, make the sales tax less regressive. For example, thirty-two states, plus the District of Columbia, exempt groceries from their state sales tax and almost all states exempt prescription drugs. Many states also exempt the sale of residential utilities, such as electricity or natural gas.

Credits

Targeted tax credits are an innovative alternative to exemptions. Usually administered through the income tax, these credits provide a flat dollar amount for each member of a family, and are available only to taxpayers with income below a certain threshold. These credits are also refundable, meaning that the value of the credit does not depend on the amount of income tax paid and the credit is given even if it exceeds the amount of income tax owed. Refundability is a particularly important aspect of credits meant to offset sales taxes; they allow access to taxpayers with little or no income tax liability who pay a substantial portion of their income in sales taxes. When refundable, sales tax credits can provide a much needed income boost to help families make ends meet.

Disadvantages of Exemptions

While both sales tax exemptions and credits can serve as valuable tools for lowering sales taxes, they differ in their impact on state tax systems and their respective claimants. The main disadvantage of sales tax exemptions is that they narrow the sales tax base (that is, the total dollar amount spent on taxable items), and can significantly reduce the amount of revenue that can be brought in through the tax. This goes against the argument generally made by economists that the sales tax base should be as broad as possible.

Here are a few key facts that lawmakers should consider when comparing the merits of these two policy options:

- Exemptions are poorly targeted. Even under a fairly progressive exemption for grocery purchases, the poorest 40 percent of taxpayers typically receive only about 25 percent of the exemption’s benefit. The rest goes to wealthier taxpayers who can more easily afford to pay the sales tax on groceries.

- While exemptions can make the sales tax less regressive, they also create a new source of unfairness: differential treatment of taxpayers at a given level of income. By exempting groceries while taxing other retail sales, lawmakers are discriminating against taxpayers who spend more of their money on non-grocery items.

- Exemptions tend to make sales tax collections more volatile. With fewer economic sectors subject to the tax, any changes in those remaining sectors can have a larger relative impact on overall tax collections. A broader tax base, on the other hand, allows tax revenues to be less sensitive to sudden swings since those swings will generally be offset by changes in purchases of other items.

- Because they lower taxes for everyone regardless of their individual need, exemptions are quite costly. Exempting groceries, for example, has the potential to reduce the revenue yield of each penny of sales tax by nearly twenty percent. This requires that lawmakers significantly increase tax rates or reduce public investments in order to offset the reduction in the tax base.

- Exemptions are an administrative challenge to policymakers, tax administrators, and retailers because any exemption requires a way of distinguishing between taxable and exempt products. For example, in some states a food item may be considered taxable based only on whether or not the seller also provides eating utensils. Exemptions require policymakers and tax administrators to make countless decisions of this sort, and retailers must be familiar with all of these rules.

- In states that allow local sales taxes, lawmakers must decide whether sales tax exemptions should apply to local taxes as well. Doing so can be costly to local governments, but failing to do so creates another layer of complication for retailers and tax administrators.

Credits: A Better Alternative

Sales tax credits offer several advantages over sales tax exemptions. Credits can be targeted to state residents only and they can be designed to apply to income groups most in need of tax relief. The precise targeting of credits allows them to be much less expensive than exemptions. Credits do not affect the sales tax base, so the long-term growth of sales tax revenue is more stable. And credits are easier for tax administrators to manage.

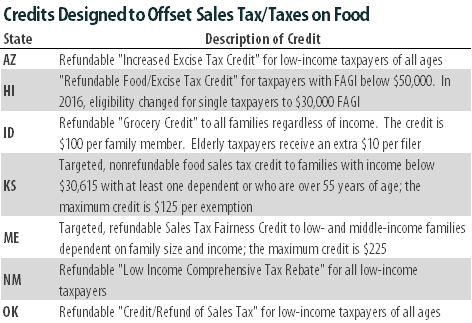

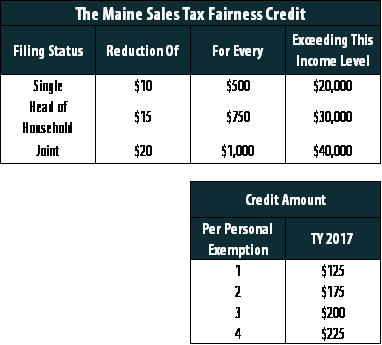

The following chart shows the details of one such program, Maine’s refundable sales tax credit. Once fully enacted, a married couple with two children making $51,000 or less will receive a refundable sales tax credit of $225. If the couple’s joint income exceeds that amount, however, they would be phased out of the program. Several states offer an income tax credit to assist in offsetting some of the sales and excise taxes that low-income families pay. Many of those credits are general, like Maine’s, while others are specifically intended to offset the impact of sales taxes on groceries in states where food is included in the tax base.

Sales tax credits do have some disadvantages. The main drawback of credits as an alternative to exemptions is the added administrative responsibility on taxpayers. All of the states that currently allow sales tax credits require taxpayers to file an application form, usually in conjunction with state income tax forms.

Eligible taxpayers who do not know about the credit, or who do not have to file an income tax form, may miss out on the chance to claim the credit. To this end, an effective outreach strategy is a critical component of any effort to provide sales tax credits. By contrast, exemptions are given automatically at the cash register—so consumers do not need to apply or even to know about them.

In lieu of state-specific sales tax credits, many states interested in mitigating the regressive effects of the sales tax have decided to rely on a state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (described in the ITEP Policy Brief, “Rewarding Work Through Earned Income Tax Credits in 2017”). State EITCs that are based on the federal credit are easy to administer since most eligible taxpayers are already claiming the credit. This approach does, however, offer state lawmakers less flexibility in deciding on the credit’s eligibility criteria. Because the EITC is currently targeted to benefit low-income working families with children it typically offers little or no benefits to older adults and workers without children in the home. Given these limitations, refundable low-income credits are a good complementary policy to state EITCs.

Sales Tax Reform: Only Part of the Solution

Exemptions and credits are both progressive options for low-income tax cuts, but each should be part of a broader strategy for tax fairness that includes a progressive, graduated personal income tax. Neither exemptions nor credits are sufficient on their own to eliminate the unfairness of any state and local tax system relying too heavily on the sales tax.