The average person on the street would have no idea that many states experienced unprecedented budget surpluses this year. Iowa, for instance, has the most structurally deficient bridges of any state with nearly 1 in 5 falling apart. The Iowa Board of Regents proposed a 4.25 percent tuition increase for all three state universities and Iowa State University is on the brink of ending its graduate history program. The state legislature has eliminated all state support for Iowa Public Radio. State park rangers are being evicted from government-owned houses and will no longer be able to respond to emergencies. Iowans will have ten fewer weeks of unemployment benefits, dropping the maximum length for benefits to just sixteen weeks.

Other state lawmakers are making similar poor choices for how to spend these unusual surpluses. In Utah, legislators’ underfunding of disability assistance has led to severe staffing shortages and in some cases, disabled people being neglected and missing basic services. Advocates in Utah for homeless people and affordable housing received less than half of their funding request in the midst of a housing crisis, sparking fears about a return to “warehouse”-style shelters. Four cities in Mississippi are under federal consent decrees to stop pollution due to neglected sewage systems in desperate need of repair. Mississippi school districts saw record increases in operating costs while being underfunded by 10.5 percent relative to the Mississippi Adequate Education Program (MAEP)’s calculation of the minimum amount each school district needs to be operational; as a result, some school districts have been forced to leave positions unfilled and delay updates to bus fleets. In Georgia, victim advocacy groups for survivors of rape, domestic violence, child abuse, and sex trafficking are facing funding shortages. The list of unmet and underfunded needs goes on.

In a relatively rosy budget year such as this, state policymakers (i.e., public servants) should be overjoyed by the opportunity to invest in public services meaningfully and to serve their most vulnerable constituents, especially since the hardship created by the pandemic left the majority of us struggling. For the first time in years, states are temporarily flush with cash for a number of reasons, including effective federal relief efforts and a rebounding economy. Yet many state legislatures squandered this unique opportunity and chose to provide handouts to top earners instead. Thus far, ten states enacted income tax rate reductions this year – Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nebraska, New York, South Carolina, and Utah (Virginia did not reduce rates but increased the standard deduction). More than half of these states are facing tax cuts that will cost over half a billion dollars when fully phased in. Other states like Arkansas, Missouri and West Virginia are working hard to pass large cuts this summer.

These decisions are, at best, puzzling and misinformed, and, at worst, calculated and harmful. Recently, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson said that the state’s $1.628 billion surplus “demonstrates the state is collecting too much in tax revenue.” But this misstates the problem. Revenues are temporarily high because of low revenue estimates, strong state economies and federal relief. This means that the Governor is setting Arkansas up for a grimmer future when the surplus inevitably dries up. Arkansas is already set to accelerate tax cuts that were going to be fully phased in by 2026, and now the Governor has proposed deeper cuts during a special session. These tax cuts will remain in effect beyond 2022 including in years when there is no federal aid and collections are lower. As Arkansas Advocates for Children & Families aptly put it:

“In the past decade or so, Arkansas Legislators have sent as many tax dollars back to the 1 percent of Arkansans making more than $503,000 annually as they’ve sent to the 80 percent of taxpayers making less than $98,000 annually. I don’t know too many Arkansans making more than half a million a year who need help right now. Do you?”

Georgia, Mississippi, and Iowa all moved from graduated income tax rates to flat taxes in the past year – a move that inevitably cuts taxes for higher earners and is paid for by raising rates on low- and middle-income families and by cutting budgets. In Georgia, former member of the House of Representatives and lobbyist Ben Harbin concluded that legislative sessions are “always easier when you have no money because you can just tell everybody ‘no.'” This year, with a bit more budgetary breathing room, it was higher-income people and corporations that were most likely to hear a ‘yes’ from state officials. Georgia lawmakers passed a multi-year tax cut plan that would reduce state revenues by $2.04 billion per year when fully implemented, with 22 percent of all tax cuts going to the top 1 percent. The 60 percent of Georgia tax filers that includes both low and middle-income households would collectively see just 16 percent of the cuts. And due to historic and present-day inequities, Black and Hispanic Georgians who, on average, earn lower incomes, would see the smallest savings. Lawmakers rejected proposals to balance cuts with common-sense revenue raisers like capping the state’s costly film tax credit or eliminating most itemized deductions.

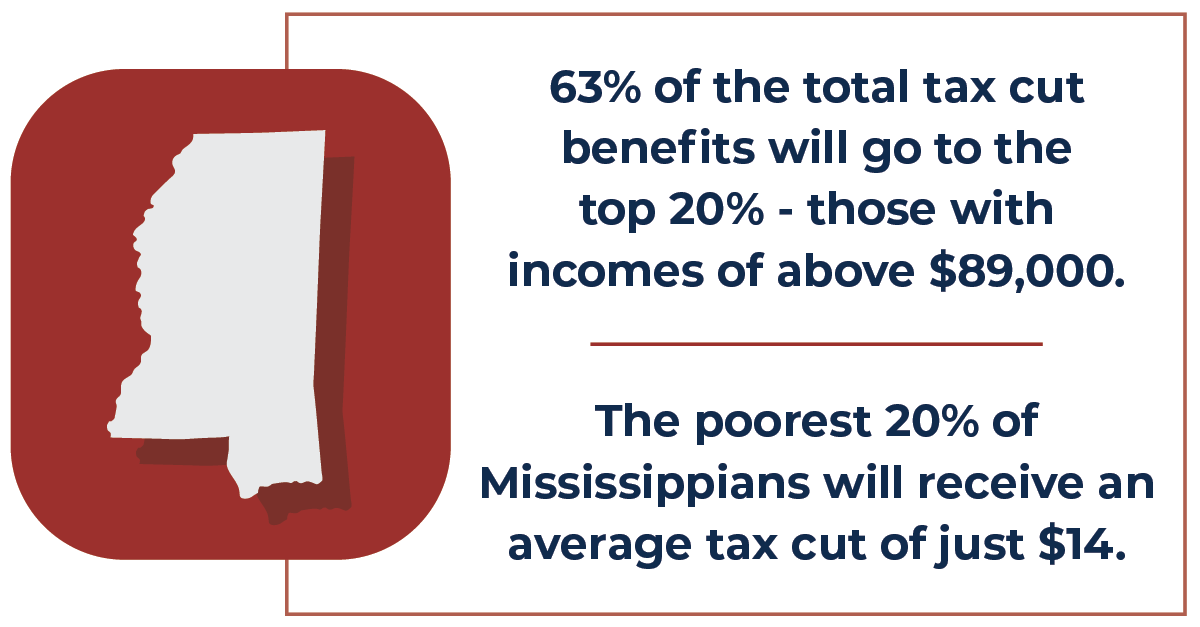

In Mississippi, lawmakers passed a massive tax cut that will create a 4 percent flat tax on incomes over $10,000. Once fully implemented, only 37 percent of the tax cut will go to Mississippians earning less than six figures while the state’s highest income households will save thousands of dollars annually. The average tax cut for white households will be nearly twice as high as the average tax cut for Black households. Instead of addressing poverty, fully funding education, investing in broadband infrastructure, or eliminating the grocery tax, as proposed in earlier discussions, Mississippi legislators decided that the best use of the funds would be to steer them disproportionately to wealthy Mississippians.

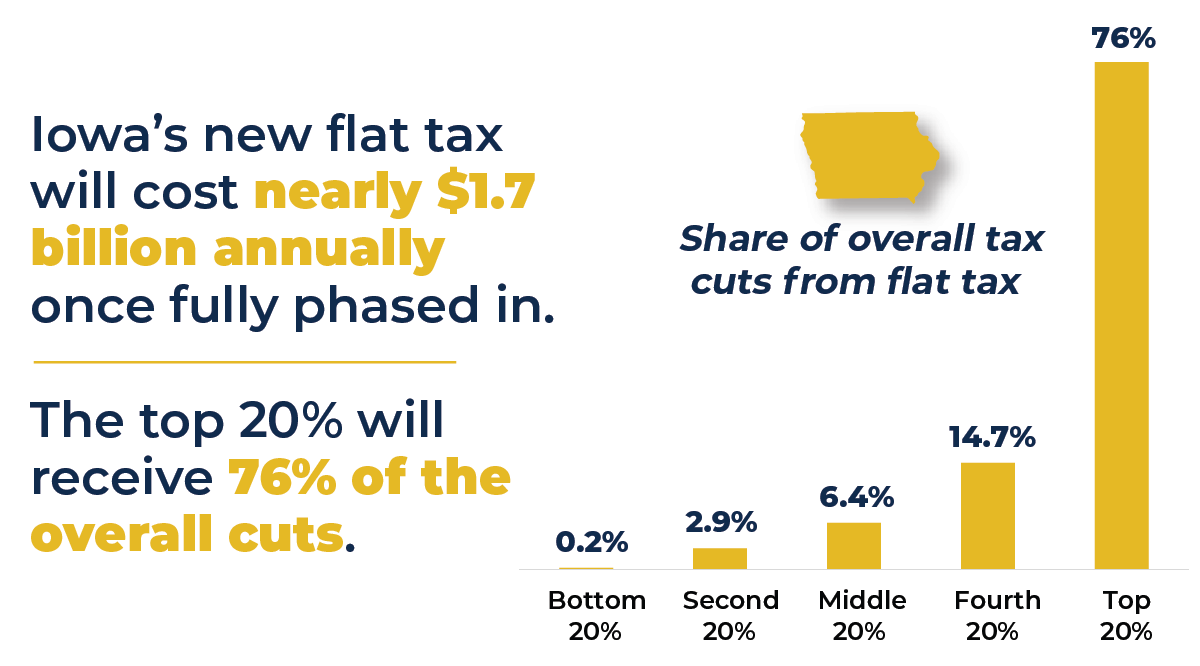

The Iowa bill will bring Iowa’s personal income tax, which has a top rate of 8.53 percent today, down to a flat 3.9 percent over the next four years. When fully phased in, many Iowans will see zero benefit while 82 percent of the tax savings will go to the top one-fourth of taxpayers who have incomes over six figures. The average millionaire will save $62,000 a year compared to just a few hundred dollars for those making $40,000 to $60,000.

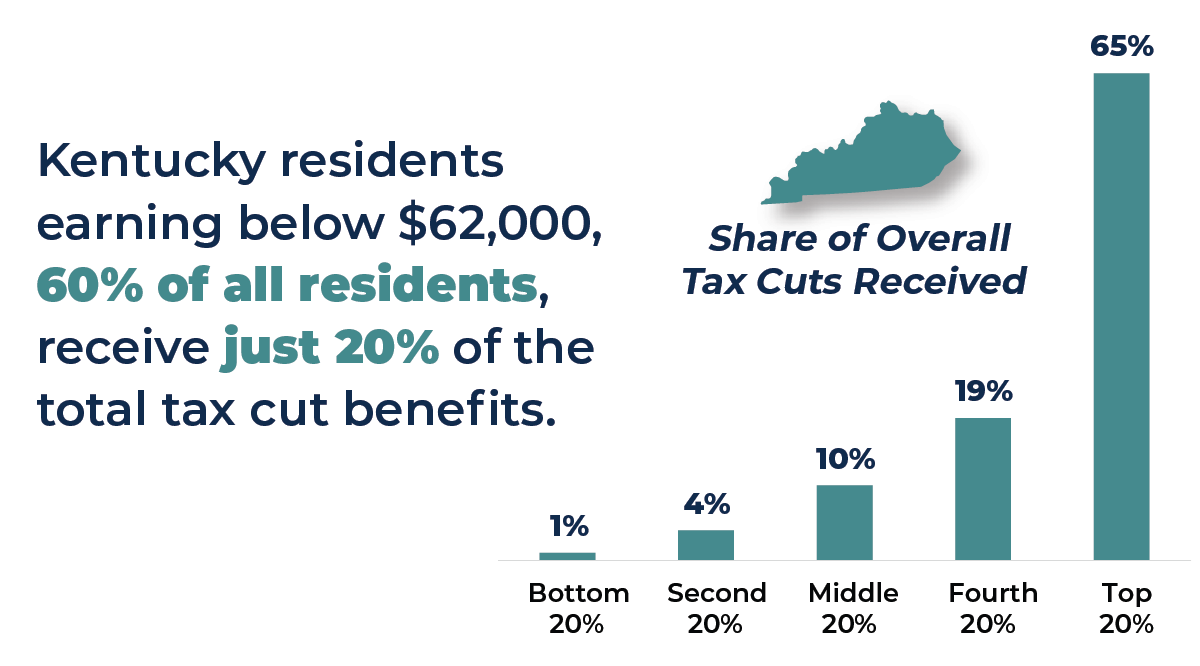

Lawmakers in a number of states are assuming that the tax cuts are affordable without any long-term strategic thinking or calculations about the compounding effects of the tax cuts or the increased costs of public services. Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb signed a $1.1 billion tax cut plan that will gradually reduce the state income tax rate from 3.23 percent to 2.9 percent. Again, most tax savings flow to the top 1 percent. The Kentucky General Assembly overrode Gov. Andy Beshear’s veto of a bill that will lower the state’s flat income tax from 5 to 4 percent over the next two years, with triggers to lower the rate further. The bill includes some modest revenue raisers but comes nowhere close to offsetting the lost revenue.

In Nebraska, nonresidents, corporations, and wealthy residents benefit the most from two bills that would phase down the top personal income tax and corporate tax rates, accelerate a measure to fully exempt Social Security income from taxation, and expand property tax credits, costing nearly $900 million altogether when fully phased in. At least 83 percent of the corporate income tax cut would flow to non-Nebraskans and nearly a third of the personal income tax cut would go to those making $560,000 or more.

After avoiding disastrous cuts in the past two regular legislative sessions, West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice is again urging lawmakers to pursue cuts during a special session. Some politicians claim that the cuts are for the “middle-class” but what is the point of saving a few hundred dollars when tax cuts contribute to rising college tuition? Or libraries close because they cannot meet the local funding requirements? As the acting director of the McDowell Public Library said, the library has already cut staff and gone from purchasing 200 to 300 books at once to just twenty-five or thirty.

Universal tax rebates and tax exemptions for social security benefits and retirement income were also popular this year. Unfortunately, few were designed to ensure families with the greatest need received the most funds. Studies show that a large share of senior tax breaks go to higher-income seniors who need them least. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explains, many state senior tax breaks were adopted at a time when poverty among seniors was more widespread; now, much greater inequality among seniors means a greater portion of state revenue loss is going towards tax preferences for wealthy seniors. Maryland legislators passed one of the costliest senior tax breaks this session – a $1.5 billion tax cut for seniors but since the credit is nonrefundable, low-income families will not be able to claim the full benefit. Iowa’s tax cut plan also eliminates all taxes on retirement income, even for extraordinarily wealthy retirees, despite the fact that most retirees already pay little to no tax in Iowa. Similarly, the one-time income tax rebates passed in at least eight states would be far more effective at reaching families in need if they were fully refundable and the income eligibility limits were lower.

At every turn, lawmakers could have made investments that would have meaningfully reduced income inequality and supported the building blocks of strong communities such as health care, infrastructure, childcare, broadband, and affordable housing. While many states made some progress in these areas, it is incredible to think what else could have happened if lawmakers had prioritized everyday families over wealthy special interests.

It would be unwise to interpret the 2022 state legislative sessions as a sign of success when the distributional impacts of these massive revenue losses by race and income tell a different story; for every couple hundred dollars a middle-income family sees in tax cuts, millionaires are seeing thousands more. And as the impacts of the revenue cuts surface, states will keep hiking tuition costs, gutting public broadcasting, putting off infrastructure updates, closing libraries, understaffing health services, privatizing state parks, and deepening racial disparities in income and wealth.