The recently enacted federal tax and spending megabill imperils states’ ability to pay for education, health care, and other public services in many ways, including by quadrupling the federal government’s cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions. States in recent years have used this cap to constrain a lucrative state tax break that mostly benefits the wealthy, but if states now continue to follow the federal lead it will cost them revenue they can ill afford.

The new law raises the SALT deduction cap from its previous level of $10,000 for all taxpayers to $40,000 for those with incomes up to $500,000, effective immediately. The cap is scheduled to revert to $10,000 in 2030, but Congress could act before then to make the higher cap permanent.

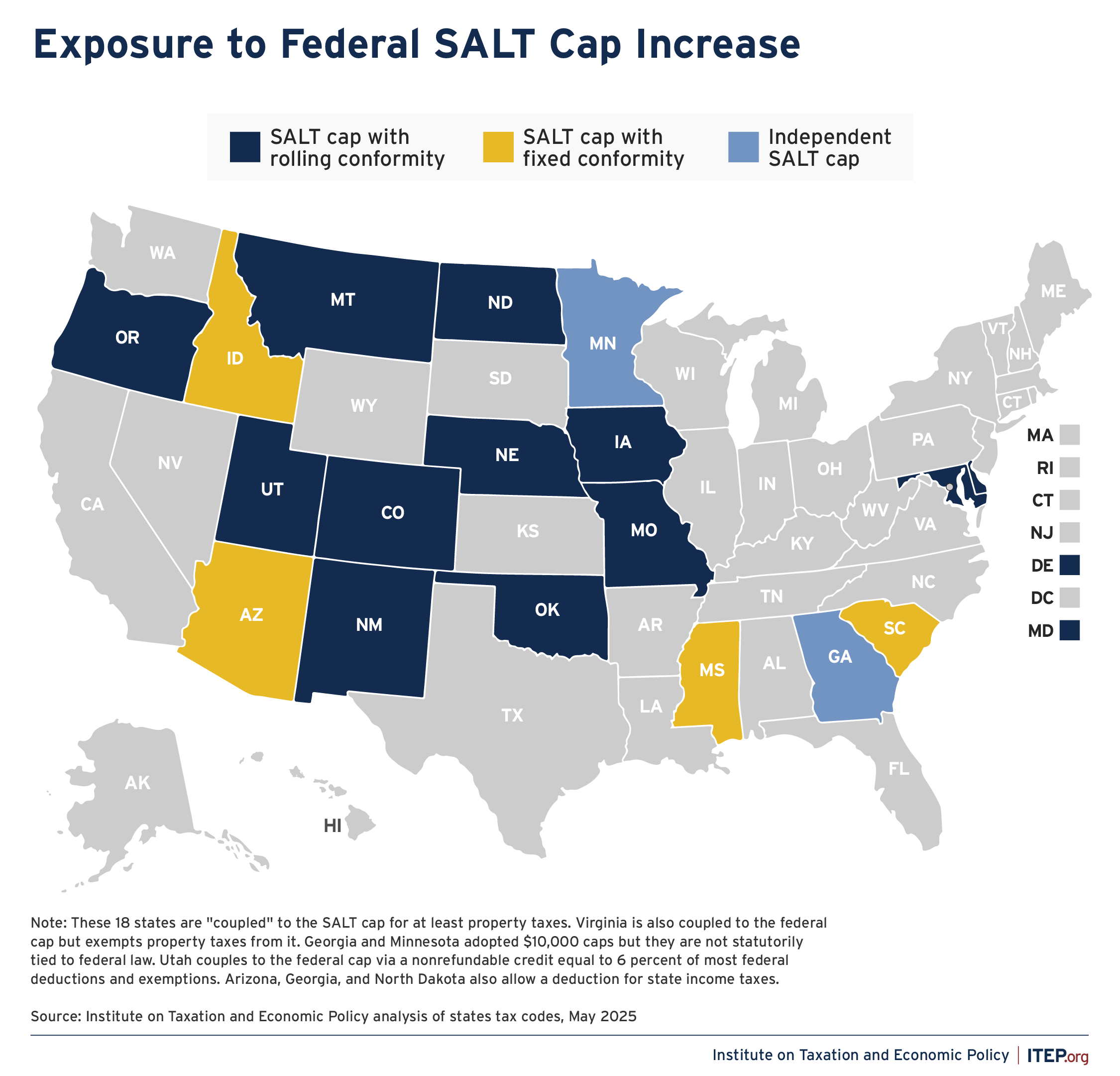

This change has immediate implications for many of the 18 states that followed the federal government’s lead in 2018 to apply the cap in their own income tax laws.1 They should now act to block this unwarranted loss of revenue by decoupling from this federal change and keeping their own cap at $10,000. And other states who allow itemized deductions but who until now have allowed unlimited SALT deductions should begin capping them, preferably at the $10,000 level or even lower. This is especially important right now, when many states are already facing significant fiscal pressures from federal budget cuts and other factors.2

Conforming to the federal SALT cap made sense in 2018, but doesn’t anymore

While the wisdom of a federal SALT cap is hotly debated, capping deductibility at $10,000 was an unambiguously good idea at the state level. States would be smart to stick with the current cap or, better yet, go even farther and repeal SALT deductions outright. Going along with a $40,000 federal SALT cap would mostly benefit a small number of relatively wealthy state residents and cost states significant revenue starting in the current fiscal year.

To understand why this is the case, it may help to know how the SALT cap came about.

Until 2018, federal law allowed a tax deduction for state and local taxes paid for people who itemized their deductions. Many middle-income taxpayers at the time were itemizers, but this deduction was most lucrative for high-income people who paid relatively higher state and local taxes.

In the 2017 tax law, President Trump and Republicans in Congress placed a cap of $10,000 on what people could deduct in state and local taxes. They did this to slightly reduce the cost of what overall was an extraordinarily expensive and regressive tax law, and to do so in a way that disproportionately affected residents of Democratic-leaning states and had less impact on their own constituents.

States often incorporate federal tax law changes into their own tax codes, so it’s not surprising that many states adopted the SALT deduction cap. In this case, it was a good idea. While the federal SALT deduction cap affected taxpayers’ ability to deduct both their state income taxes and their state property taxes, the primary effect of bringing the cap into state income tax calculations was to limit the deductibility of property taxes.

That’s because, even though the federal cap covers state income taxes as well as property taxes, only a few states allow taxpayers to deduct state income taxes from state income taxes – an absurd circular deduction.3 With state income taxes out of the calculation, most states’ SALT deductions are primarily write-offs for real estate property taxes paid. In those states that abided by the new federal cap of $10,000, homeowners were able to deduct up to $10,000 in property taxes but no more.

Now the federal SALT deduction cap has gone up to $40,000 for most taxpayers; for those with incomes over $500,000, the cap gradually declines as income rises to a flat level of $10,000 for those with incomes over $600,000.

So what will happen in the states?

There’s every reason to fear that states that previously conformed to the $10,000 cap will immediately raise their caps to $40,000, either automatically or through new legislation.

The new federal cap takes effect for tax year 2025, i.e. for taxes filed in early 2026. So states that conform automatically to federal tax law (“rolling conformity”) must act immediately to ensure that the new cap does not automatically reduce revenue in the current fiscal year, which in most states began July 16, 2025.

States that do not automatically conform (“fixed date conformity”) will likely consider a conformity bill in their 2026 legislative sessions or sooner, at which point they can elect to retain the $10,000 cap or eliminate the deduction entirely.

The new SALT cap is a big tax break for well-off property owners

The immediate revenue loss is one major reason to retain the $10,000 cap (or, even better, end SALT deductibility altogether). Another reason is that the cap is an effective way to constrain a lucrative tax break for a small fraction of higher-income, higher-wealth households who own one or more expensive houses. (Property taxes on vacation houses are deductible, even if they’re located in another state.) Most homeowners don’t itemize their deductions and most of those who do already pay less than $10,000 in property taxes.

There are 86 million owner-occupied houses in the U.S., but only about 13 million of those homeowners claim an itemized property tax deduction, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau and Internal Revenue Service data.4 And for most of those 13 million homeowners who itemize, their average property tax deductions are below the $10,000 cap. (See table.) Raising the SALT cap won’t help them.

Moreover, in states that apply graduated tax brackets, the deduction ends up being worth more, per dollar deducted, to high-income people in high tax brackets.

Even with the new $500,000-$600,000 income limit, most of the benefit from raising the cap will go to a relatively small number of taxpayers with incomes between $200,000 and $600,000 who have property tax bills above $10,000.

Raising the SALT cap is an upside-down approach to property tax reform

The fact that raising the cap mostly benefits the wealthy invalidates the argument that doing so will result in meaningful help for those struggling to afford property taxes.

In general, households with incomes over $200,000 are not a group for whom property taxes are a problem. Those same IRS data show that for those higher-income households, property tax payments as a share of income are less than half as high as they are for lower-income homeowners. (Families who rent their homes also pay property taxes in the form of higher rents, but renters aren’t eligible for these deductions at all.)

Helping homeowners manage their property tax bills is an important priority for states. But conforming to this federal change would be an expensive and inequitable approach that would provide most of its benefit precisely to the people who need it the least.

Instead, states can look at other tools available to mitigate high property taxes for those who have trouble affording them, like homestead exemptions, deferral programs or, best of all, circuit breakers that ensure homeowners and renters alike are not asked to pay more property tax than they can afford.5

FIGURE 1

TABLE 1

Who Itemizes Their Taxes in the U.S.?

| Income group | Tax filers | Itemizers | Itemizers as share of all tax filers |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $100,000 | 122,952,000 | 5,753,000 | 4.70% | |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | 25,887,000 | 4,746,000 | 18.30% | |

| $200,000 to $500,000 | 10,018,000 | 3,330,000 | 33.20% | |

| $500,000 or more | 2,479,000 | 1,461,000 | 58.90% | |

| All taxpayers | 161,336,000 | 15,290,000 | 9.50% |

Source: ITEP calculations from Internal Revenue Service data for tax year 2022

TABLE 2

How Much Property Taxes Do Itemizers Pay?

| Income group | Average income of itemizers | Average real property tax deduction | Average deduction as share of average income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $100,000 | $60,000 | $5,400 | 9.0% | |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | $141,800 | $6,400 | 4.5% | |

| $200,000 to $500,000 | $303,700 | $9,600 | 3.2% | |

| $500,000 or more | $1,902,300 | $20,500 | 1.1% | |

| All taxpayers | $314,500 | $8,300 | 2.6% |

Note: Not all itemizers claim a real property tax deduction, so the average here is among those who do. Source: ITEP calculations from Internal Revenue Service data for tax year 2022.

Source: ITEP calculations from Internal Revenue Service data for tax year 2022

Endnotes

- 1. In addition to the 18 states shown in Figure 1, Virginia is coupled to the cap for sales taxes only. Note also that passage of the federal law is going to lead to lower revenues in Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Oklahoma, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. These states allow only those people who itemize their federal deductions the option to itemize at the state level as well, so a higher federal SALT cap that leads more people to itemize federally will lead to more taxpayers itemizing and thus cause revenue loss in these states even though these states are not coupled to the SALT cap itself.

- 2. Liz Farmer, “States Tread Carefully With Budgets as Gaps and Revenue Uncertainty Loom,” Pew Charitable Trusts, July 10, 2025; Wesley Tharpe, “Roundup: State Budgets Increasingly Strained as House, Senate Republican Plans Would Impose Major Costs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 24, 2025.

- 3. Arizona, Georgia, and North Dakota are the only three states that conform to the SALT cap and also allow a state deduction for state income taxes paid, adding to their revenue risk. A fourth state, Hawaii, allows a deduction for state income taxes but has its own state-specific cap.

- 4. U.S. Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey,” Table 4, April 2025; and Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Division, “Individual Income Tax Returns with Itemized Deductions,” Publication 1304, Table 2.1, October 2024.

- 5. See Kamolika Das and Rita Jefferson, “Housing Affordability and Property Taxes: How to Actually Move the Needle,” ITEP, March 2025; and Carl Davis and Brakeyshia Samms, “Preventing an Overload: How Property Tax Circuit Breakers Promote Housing Affordability,” ITEP, May 2023.