Key takeaways

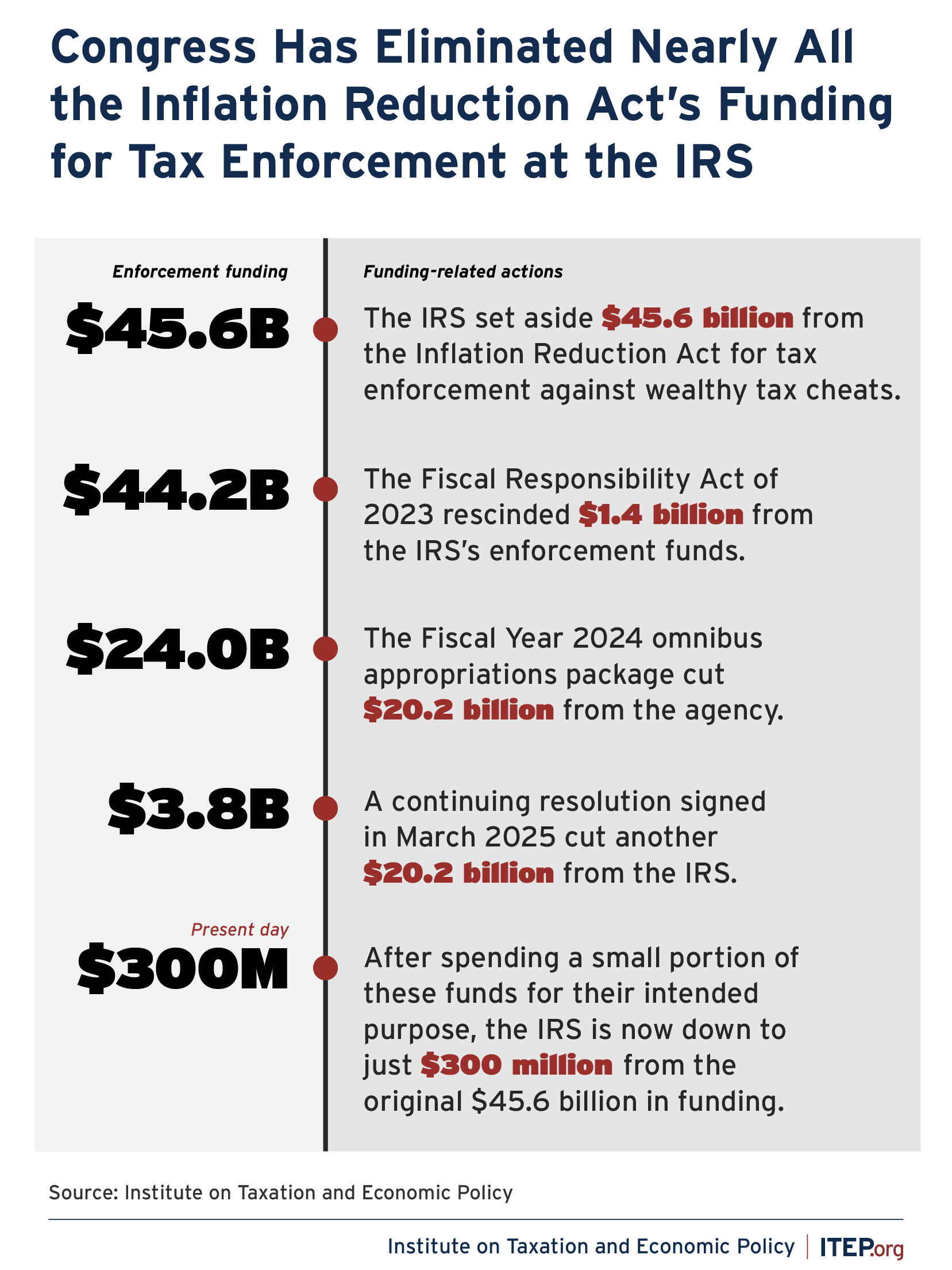

- Congressional leaders have eliminated nearly all the Inflation Reduction Act’s $45.6 billion in new funding for tax enforcement at the IRS in just three years (it was supposed to last for 10). That account is down to roughly $300 million at the end of June, with only $3.5 billion spent for its intended purpose and the rest abandoned in a series of ill-advised political deals.

- This funding was essential to helping our tax system function properly by collecting the taxes owed by wealthy households and profitable corporations.

- The funding boost would also have modestly reduced the deficit, since tax enforcement funding more than pays for itself. Killing it puts additional pressure on the growing deficit.

As the media and the public focus on Congressional negotiations that may or may not avert a government shutdown, Republican lawmakers are quietly luring their Democratic colleagues into weakening the IRS, just as they did during the previous government funding showdown in the spring and on several occasions before that.

Tucked in the Senate’s bipartisan FY2026 bill (S.258) to fund the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education is language rescinding $11.7 billion from the IRS’s operations budget, which had been provided by 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

In the spring, the Republicans succeeded in eliminating virtually all the $45.6 billion provided by the IRA for tax enforcement against high-income tax cheats. Having completed that mission, they are now moving on to attack the funding for IRS operations, which affects everyone trying to file their taxes.

To find our way out of this mess, we need to understand how we got here.

The IRA provided the IRS with $80 billion in new mandatory funding designed to bolster the agency’s regular annual base funding for the next decade. While the base funding is all about “keeping the lights on” and covering the agency’s routine activities, the mandatory money was designed to be transformational, filling in long-standing gaps, upgrading 1960s-era technology, and bringing the country’s accounts receivable department into the 21st century.

Of that total, a little under half was earmarked for operations support ($25.3 billion), taxpayer services ($3.2 billion), business systems modernization ($4.8 billion), and oversight ($557.5 million).

Tax enforcement was supposed to receive the rest: roughly $45.6 billion to help the agency recoup some of the hundreds of billions in revenue lost to federal coffers due to wealthy and corporate tax avoidance. This was a smart, fiscally responsible investment which should have had broad appeal to anyone serious about addressing annual deficits. After all, as the Congressional Budget Office routinely finds, this funding pays for itself many times over.

But now an account that had once held close to $46 billion and was intended to help the IRS collect more of what is owed by rich households and profitable corporations through 2031, is down to roughly $300 million (based on expenditures through June 30) and will likely be depleted before the end of the year.

Figure 1

The ramifications of this successful assault on IRS funding have largely flown under the radar. But these attacks should be viewed as a tax giveaway to the ultra-rich that is every bit as egregious as the massive tax cuts for the well-off included in the recently enacted Trump megabill.

Funding tax enforcement should be a no-brainer

At first glance, ensuring that the public follows the laws that Congress has enacted seems like something Congress would support without much controversy. One might even expect that to be especially true for tax compliance, since tax enforcement raises revenue without requiring elected officials to raise existing taxes or create new ones.

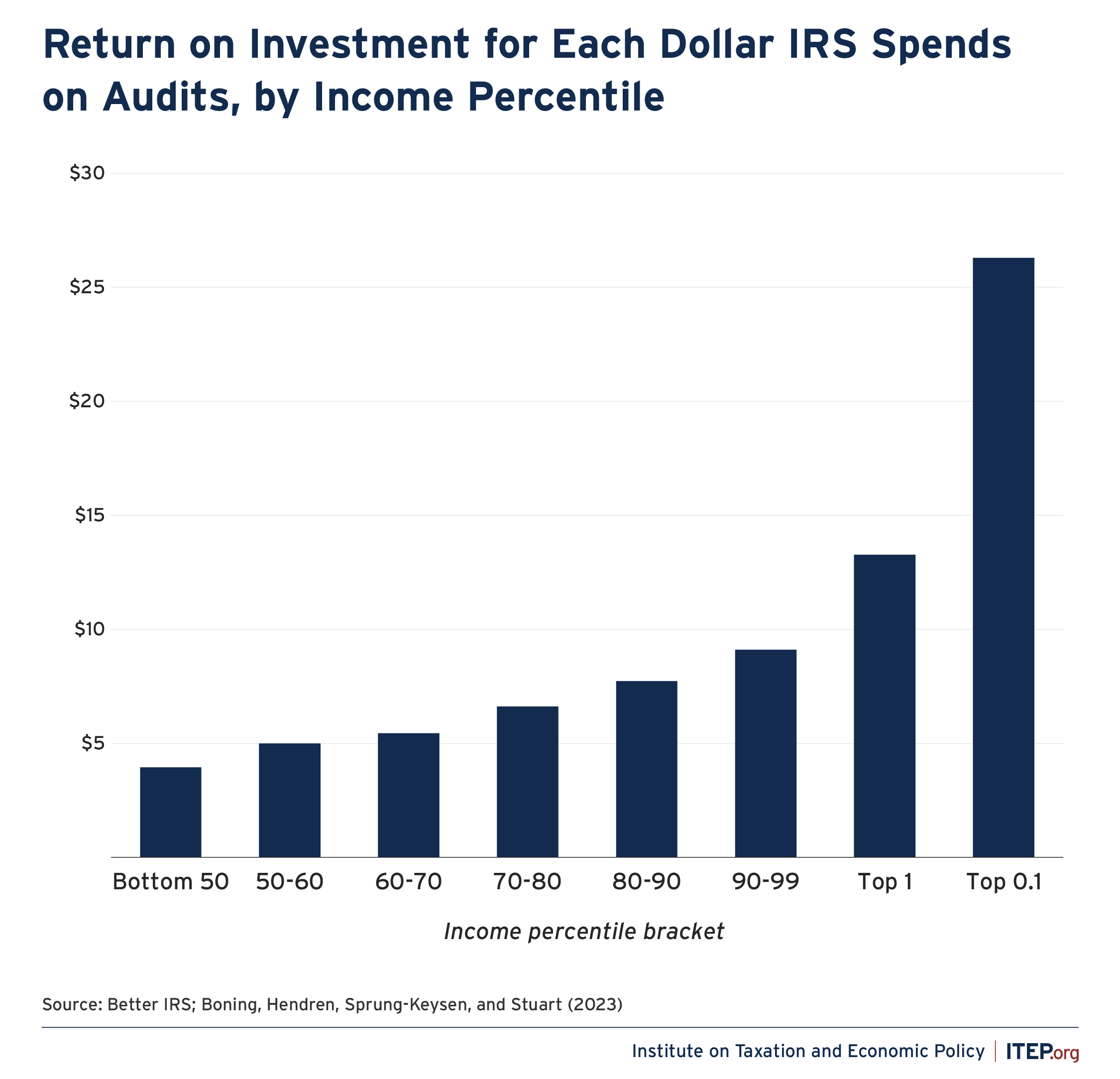

A well-funded IRS fully staffed up with highly trained experts can get a huge bang for its buck, raising $12 for every $1 it spends on auditing the richest 10 percent of households. Some estimates suggest that the true benefit may be even higher when it comes to auditing the ultra-ultra-rich—closer to $26 per every $1 spent auditing the top 0.1 percent. Part of this return on investment comes through spurring improved voluntary compliance. Just like drivers tend to slow down when they’ve been dinged by a traffic camera, wealthy taxpayers tend to be more vigilant about paying what they owe in the years following an audit.

Figure 2

Yet attacking the IRS has been a popular GOP pastime since the Gingrich era—with “abolish the IRS” serving as a regular campaign pitch to GOP base voters. Between 2010 and 2021, the House Tea Party majority led a sustained attack on the agency that cut funding for IRS enforcement by 25 percent, leading to a 40 percent reduction in the number of dedicated revenue agents.

As a result, audit rates for large corporations fell 54 percent and audit rates for millionaires dropped by a staggering 71 percent between 2010 and 2019, according to a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of Treasury data.

Auditing regular taxpayers is easy, and relatively cheap, and although each individual audit doesn’t raise much revenue, one agent can alone handle dozens of cases. Auditing the ultra-rich, however, requires teams of experienced personnel trained in combing through complicated business arrangements, sophisticated tax shelters, and tax returns that can run hundreds of pages.

That’s why, in 2020, the last year of the first Trump administration, a grossly underfunded IRS audited low-income tax filers receiving the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) at a higher rate than it audited millionaires for the first time in history.

And as a result, the annual tax gap— the difference between what is legally owed and what is actually collected— grew. Early in 2021, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig, appointed by Donald Trump, warned Congress that the gap could be as high as $1 trillion, and urged lawmakers to take action to improve enforcement.

Bipartisan agreement to fix the IRS fell apart

In June 2021, a bipartisan group of 20 senators unveiled a $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure investment package paid for, in part, by a $40 billion increase to IRS tax enforcement capabilities. The new enforcement funding was expected to raise $100 billion in revenue from corporations and individuals making over $400,000.

Republican Senators Shelley Moore Capito and Susan Collins, for example, were quoted as saying “regular taxpayers can’t stand it when somebody is not paying their fair share,” and “providing IRS with more resources so that people who were evading taxes [pay what] they owe is a good idea.” Compared to the perceived political pain of raising new taxes, enforcing existing tax laws promised to be a win-win for members on both sides of the aisle, providing an influx of new revenue without violating conservatives’ no-new-taxes pledges.

But the bipartisan enthusiasm for enforcing our nation’s tax laws was soon short-circuited by the same special interests that had benefited from the IRS’s decline in the first place. As Politico reported that May, “Conservative groups have launched a campaign of TV ads, social media messages and emails to supporters criticizing the proposal to hire nearly 87,000 new IRS workers over the next decade to collect money from tax cheats.” Soon, anti-IRS messages were flooding the airwaves with ominous warnings that Biden’s IRS was “aggressively coming for every dime they can grab from your house.”

Eventually Senate Republicans backed away from IRS funding and the bipartisan infrastructure package was eventually enacted without tax enforcement funding and with a $256 billion revenue shortfall built in.

Inflation Reduction Act to the rescue

Despite this setback, the Biden administration remained committed to its plan to overhaul the IRS through an infusion of new mandatory funding (on top of its annual discretionary funding) that would ensure the agency had the resources to modernize its aging technology, improve customer service, and crack down on wealthy and corporate tax avoidance and evasion.

And so, in the summer of 2022 a pared-down version of the Biden tax plan was enacted as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). IRS enforcement funding was one of the few tax provisions that made it into the final bill (along with an important corporate alternative minimum tax)—and the one designed to ensure the successful implementation of the Act’s other tax provisions.

In the heady months that followed, the IRS dove into cracking down on rich tax cheats and rolled out an ambitious 10-year spending plan that envisioned hiring “hundreds of employees in the coming years with skills to undertake those audits and to transform the agency’s technology to better spot noncompliance.”

Despite the inherently slow nature of hiring highly skilled personnel, the administration’s focus on auditing the ultra-rich paid off relatively quickly. By fall of 2024, the Biden IRS had announced that it had recovered $1.3 billion from “high-income, high-wealth individuals,” including $172 million from 21,000 wealthy taxpayers who had not filed tax returns since 2017.

To reduce the debt, cripple the taxman?

To best understand how the IRA money for tax enforcement disappeared, we need to travel back to 2011. As the economy struggled to recover from global financial collapse, President Obama faced an extremist House Republican majority threatening to default on the federal debt unless he agreed to deep spending cuts. He capitulated, and the resulting Budget Control Act unleashed years of chaos across the federal government, negatively impacting everything from federal research to transportation and infrastructure.

This was also a cautionary tale about legitimizing debt-limit hostage-taking. Two years later, Obama warned against creating “a situation in which each time the United States is called upon to pay its bills, the other party can simply sit there and say, ‘Well, we’re not going to pay the bills unless you give us what we want.’ That changes the constitutional structure of this government entirely.”

By 2023, with the lingering economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic playing the same role that those of the Great Recession had 12 years before, the circumstances were once again ripe for an extremist House Republican majority to hold a first-term Democratic president hostage as he grappled with a global economic crisis. After months of suggesting that he wouldn’t negotiate over the debt limit, President Biden suddenly changed course and agreed to a deal with Speaker McCarthy.

In exchange for suspending the debt limit until January 2025, the deal—a mixture of immediate legislative changes and informal “sidecar” agreements designed to guide future legislation—would impose unrealistically low caps on discretionary spending, create new red-tape bureaucracy for older adults receiving food assistance, claw back billions in unspent Covid relief funds, and cut over $20 billion of IRS’s mandatory funds over the next two fiscal years.

A wolf in sheep’s clothing

The first official cut was deceptively small, rescinding only $1.4 billion of the IRS’s IRA enforcement funds.[1] Since most observers focused on the IRA’s headline figure of “$80 billion” for the IRS, this seemed like a drop in the bucket. But the real cuts were coming next, and the real total wasn’t $80 billion, it was just shy of $46 billion—the amount designated for enforcement.

Here’s how the deal was supposed to work: House Republicans would agree to boost non-defense discretionary spending above the so-called Fiscal Responsibility Act’s caps in upcoming appropriations bills. In exchange, Senate Democrats would cut the IRS’s IRA enforcement money by $10 billion in Fiscal Year 2024 and another $10.2 billion the next fiscal year. This sleight of hand would let Republicans pretend they were “paying for” the boost to non-defense spending, even as the real-world effect was to slash revenues and increase the deficit.

But it didn’t work that way. Instead, in January 2024 with a partial government shutdown looming, House Republicans and Senate Democrats struck a deal that would keep the topline spending level, but only with additional concessions from Democrats— including frontloading all of the planned IRS rescissions into the first fiscal year, leaving the question of Fiscal Year 2025 unresolved.

Each side messaged the deal differently, with Democrats arguing that the IRS cuts that Biden had agreed to were now fulfilled and Republicans claiming they’d won “an additional $10 billion in cuts to the IRS mandatory funding” with more cuts to come in Fiscal Year 2025.

Advocates cautioned Democratic leadership that the deal was a bad one, noting that it created a $70 billion hole in the budget that Congress would have to fill “simply to maintain spending at current levels and Speaker Johnson is already predicting additional IRS cuts next fiscal year.”

“This is why,” the advocates continued, “it’s essential for you to unequivocally state your strong opposition to any further reductions in IRS funding.”

But the administration assured its allies in Congress that the IRS could easily absorb the cuts, and that it would simply reduce by two years the 10-year runway created by the IRA. That argument was based on the highly implausible notion that it would be easy enough for a future Congress to simply provide more IRS funding in another six years, despite the previous two decades of underfunding. But it was enough to convince Democratic leadership and senior appropriators.

With the topline question settled, Congress passed a Fiscal Year 2024 omnibus appropriations package in March that included the entire $20.2 billion IRS rescission in one fell swoop.

And thus the transformational account had become a piggybank— and not only at the legislative level. Behind the scenes, IRS leadership was also transferring funds out of the enforcement account to backfill gaps in other parts of their base budget, in part to ensure the public’s experience with tax filing season went off without (too many) hitches.

As bad as it looked to outside observers, the reality was worse.

IRS cuts on autopilot

In September 2024, Congress passed a continuing resolution (CR) extending Fiscal Year 2024 policies and funding levels through December (it would normally have ended September 30). Unfortunately, passing a CR instead of writing a new appropriations package comes with its own complications.

As the name suggests, a continuing resolution simply extends the previous year’s language, unless an explicit exception (an “anomaly” in congressional parlance) is included to strip out or alter that language. The 2024 law included a $20.2 billion rescission to IRS funding, so absent an anomaly, the old language automatically replicated itself for the new fiscal year, like a dangerous mutation that gets passed on every time a cell replicates.

The CR didn’t formally rescind the IRS’s funding by an additional $20.2 billion, but it did block the agency from obligating any of those funds during its duration.

White House staff and Democratic leadership explained to advocates that they hadn’t put up a fight over the IRS anomaly in September because the IRS could survive until December without facing a shortfall. But, they promised, in December they would absolutely stand their ground.[2]

In December, reeling from the election results, Democratic leadership once again declined to fight for the anomaly, arguing that the IRS could make it until March without facing a shortfall. Besides, they said, there was no need to fight over the anomaly right then, because Republicans would have to write a new bill come March regardless, and that new bill wouldn’t carry the bad “mutation” of the IRS cuts.

When pressed, appropriators noted that while Republicans could technically carry forward the IRS cuts by simply extending the 2024 language again, “that’s not how it’s ever been done.”

It doesn’t take an astute political scientist to guess what happened next.

Republican leadership crafted a CR that stealthily repeated in Fiscal Year 2025 the $20.2 billion cut to IRS that was included in Fiscal Year 2024—along with a host of other highly partisan provisions—and then dared Senate Democrats to blink. Senate Democrats blinked. And just like that, a $45.6 billion account was slashed by 92 percent.

Combined with the IRS’s spending, the mandatory enforcement account is close to gone, if not entirely gone. And Republicans, impressively, didn’t have to do much of anything at all to win their number one biggest priority: protecting rich tax cheats.

[1] The legislative text of the Fiscal Responsibility Act allowed the rescission to be withdrawn across a number of IRS’s IRA accounts, but the Biden Administration chose to pull the entire rescission from enforcement, specifically Section 10301(1)(A)(ii) of the IRA.

[2] The author was an active participant in these conversations from September 2024 through March 2025 and is providing a firsthand account.