Key findings

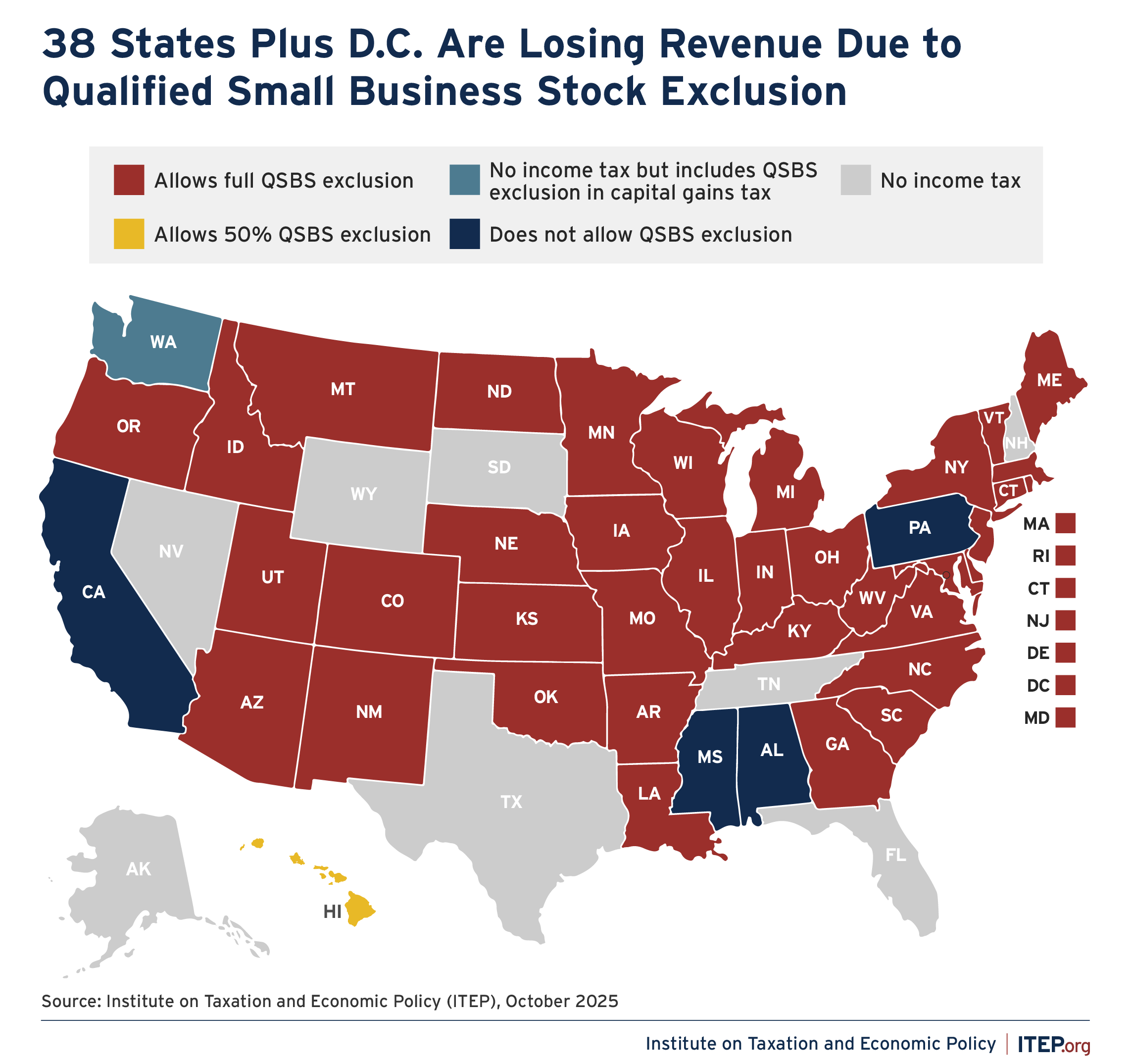

- The federal Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) exemption will soon cause 38 states plus the District of Columbia to lose $1.2 billion in annual tax revenue.

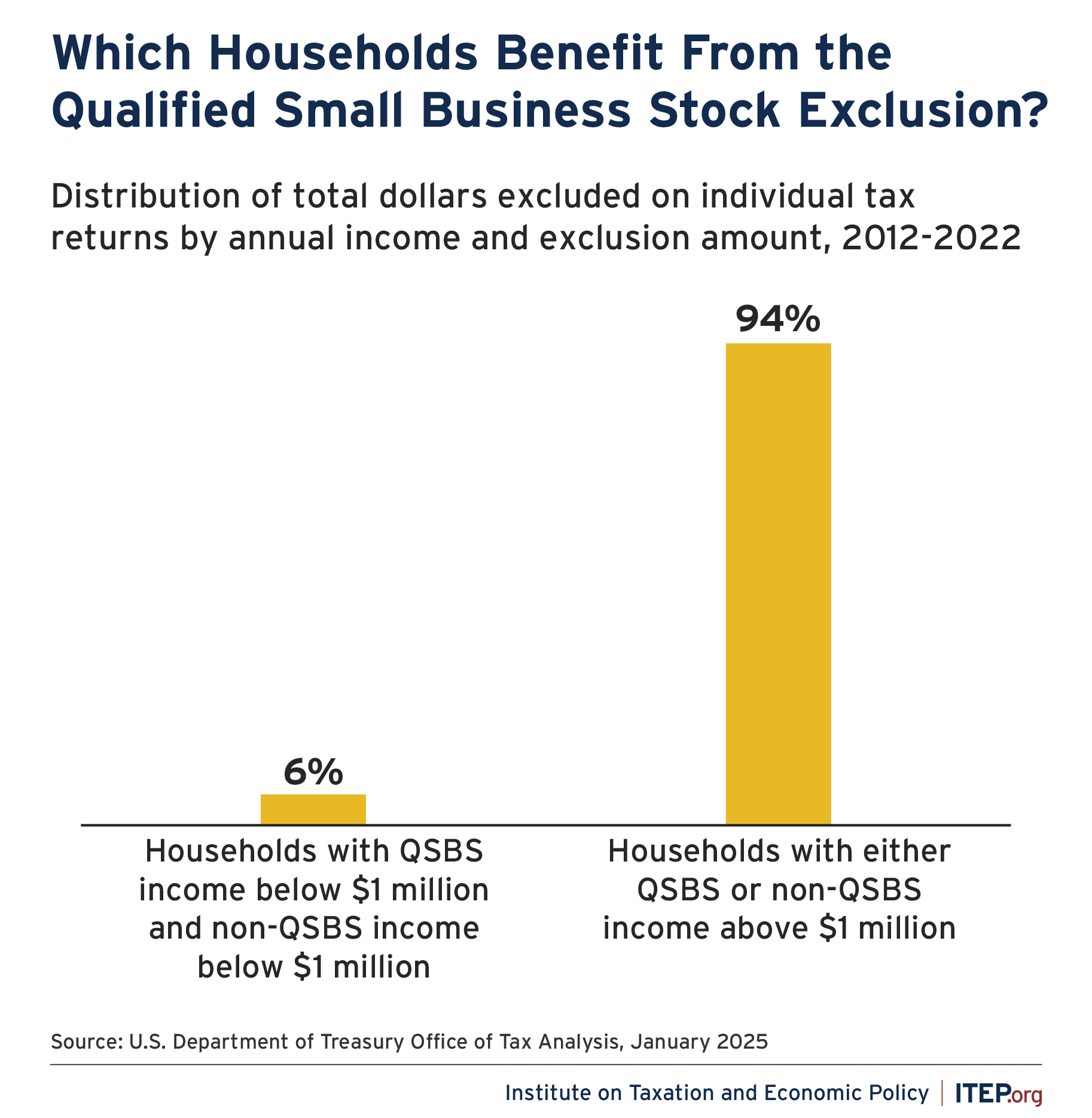

- The tax break, which was expanded in the 2025 federal tax law, benefits few small businesses. Nationally, 94 percent of the exclusion goes to households with annual income over $1 million.

- States can opt out of this tax break with a simple change, preserving critical revenue for public services in the process.

- California, home to many of the nation’s wealthiest venture capitalists, is one of four states that currently don’t allow this exemption.

Introduction

Some 38 states plus the District of Columbia will soon be losing $1.2 billion in annual tax revenue thanks to a recently expanded tax break mostly benefiting multimillionaire and billionaire venture capitalists.

Fortunately, any state can erase this loophole with a simple statutory change. In so doing, a state can keep resources in-state and protect revenues that are crucial for funding education, health care, and other services.

The culprit is an arcane provision of the federal income tax code that has been in existence for decades, but which is now exploding in cost. This provision allows wealthy venture capitalists and others to receive a 100 percent tax exemption when they cash out their early-stage investments in companies that have soared in value. Lawmakers named the provision the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) exemption, but the law doesn’t limit investments just to small businesses by any conventional measure.

The explosion in cost is occurring both because tax lawyers have found creative ways to exploit it and because Congress has expanded it. Individual QSBS claims reached over $42 billion in 2021 alone, an amount exceeding 2.5 percent of all individual capital gains realizations that year, according to recent U.S. Treasury Department research. Nearly 94 percent of the exclusions were claimed by people with more than $1 million of annual income derived either from QSBS or other sources – the top one-half of 1 percent of the U.S. income distribution. Trusts and estates claimed another $9 billion in QSBS exemptions.

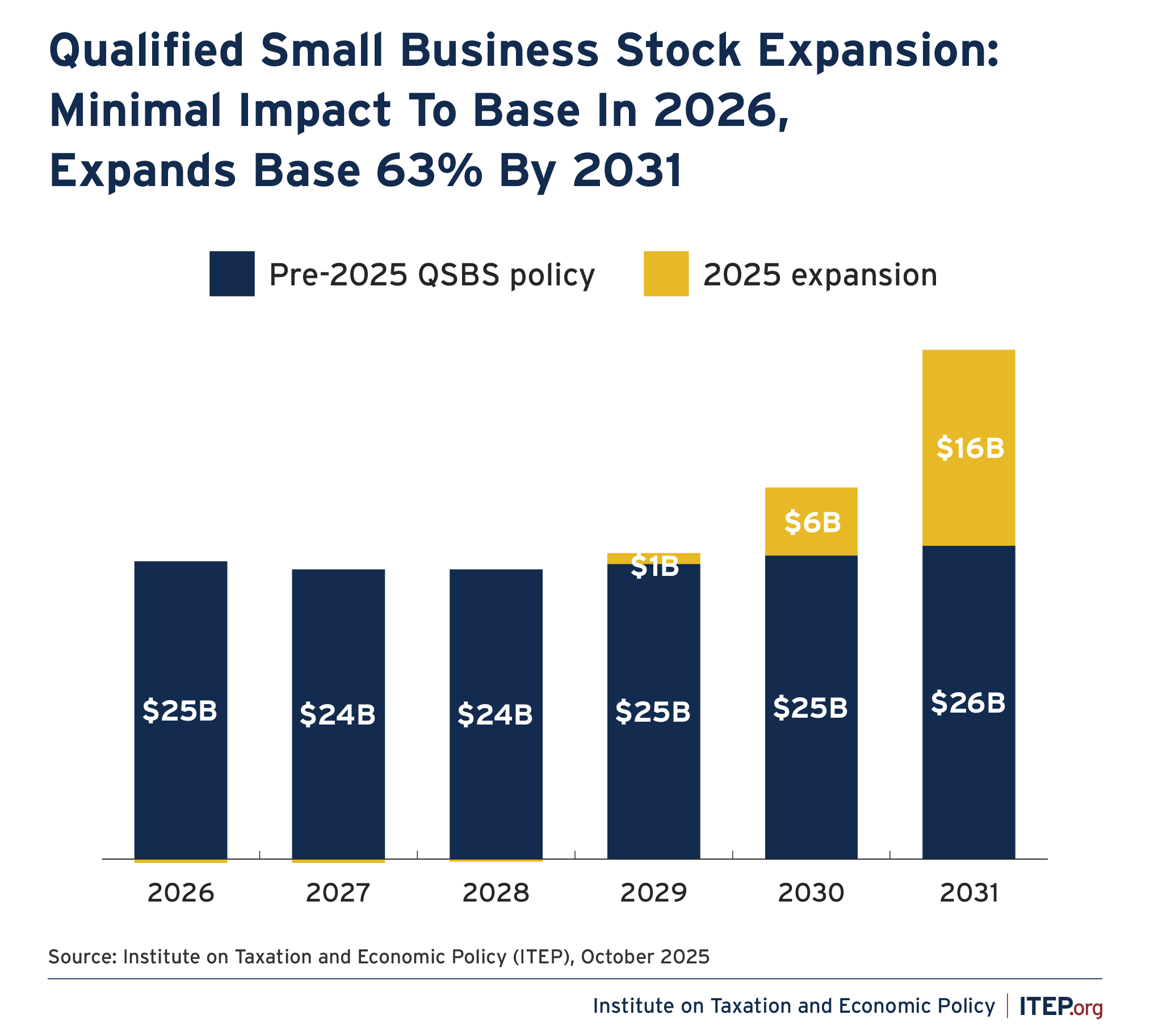

Despite this provision’s increasing cost and regressive tilt, the new federal tax law loosens the rules to allow even more wealthy investors to qualify for it, further increasing the cost. According to our estimates, this expansion will boost the cost of the exclusion by almost two thirds in 2031.

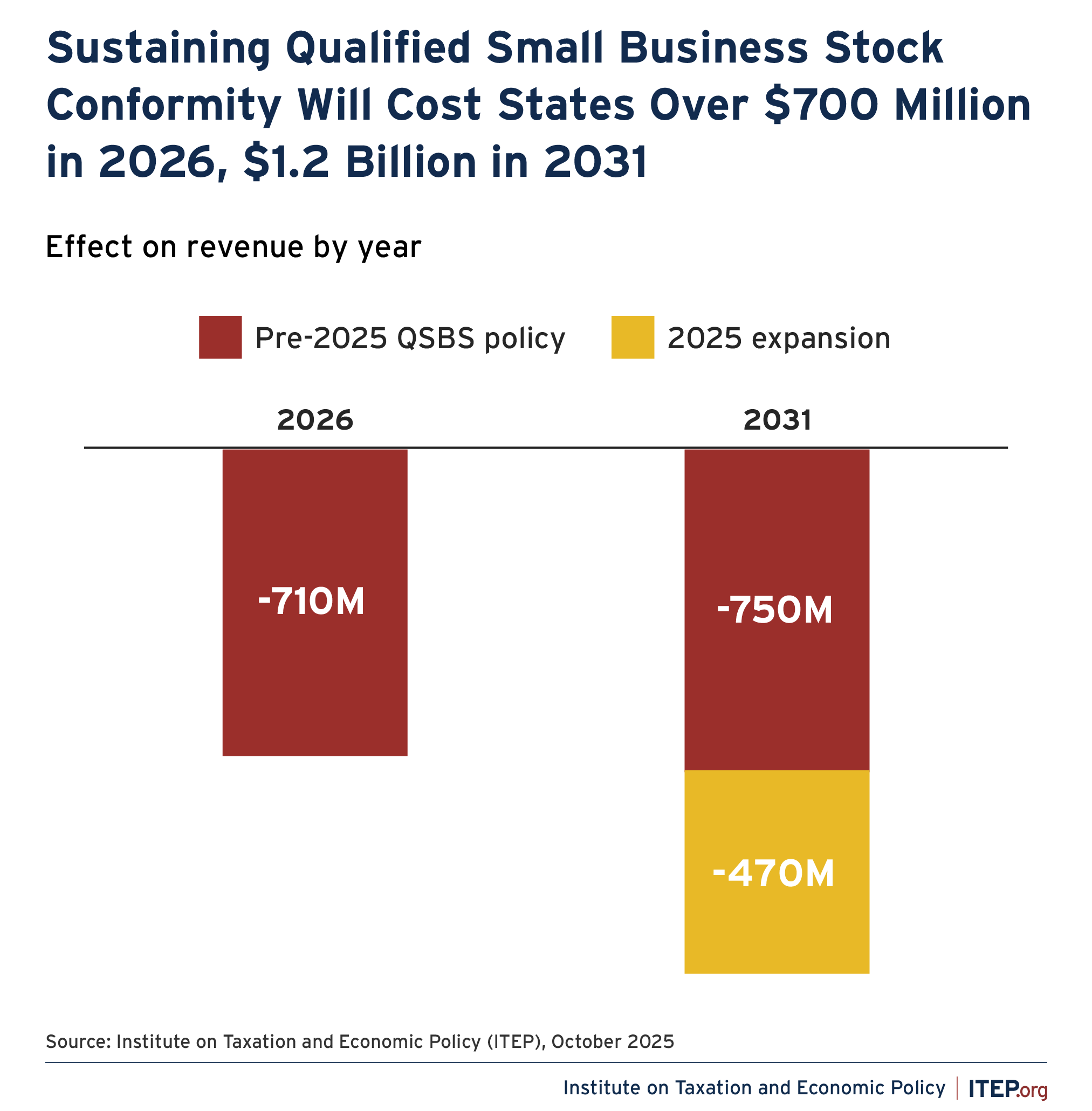

If states fail to act to protect their revenue streams, this one tax break for wealthy investors will cost them a combined $710 million in 2026, rising to $1.2 billion in 2031. At present, only a few states – most notably, California, home to many of the nation’s wealthiest venture capitalists, as well as Alabama, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania – disallow the QSBS exclusion. But with its cost rising so rapidly and state budgets already under pressure due to federal cuts, more states should consider doing so. Eliminating the loophole is a simple statutory change that – as California’s example shows – will not have a discernable impact on small businesses or capital investment in the state, but will preserve funding for schools, hospitals, and other important public services.

New data reveal the growing cost and regressivity of QSBS – and the Trump tax bill is making it worse

The QSBS exemption was enacted in the 1990s, with the stated intent of sparking investment in emerging companies, especially in the then-fledgling tech industry. But it was largely dormant until the early 2010s, when a series of federal changes made it much more lucrative and law firms pioneered new strategies to exploit it for their wealthy clients. Because QSBS required a five-year holding period, it then took several years for these changes to start affecting revenue.

In 2012, QSBS realizations were equivalent to only about one-quarter of 1 percent of capital gains realized that year. By the early 2020s, that proportion had grown to 2.55 percent of all realized capital gains – a 10-fold increase. News reports and emerging research suggest that it has been particularly lucrative for investors who have accumulated wealth in technology companies, particularly venture capitalists putting money into business expansions.

This cost explosion was documented in a January 2025 study by a team of U.S. Treasury economists. They reviewed tax returns from 2012 through 2022 and discovered that the subsidy was ballooning in cost and that its benefits were highly concentrated among very well-off investors.

They found that 74 percent of QSBS exclusions were claimed by households with annual income of $1 million or more, not including the value of the QSBS exclusion. An additional 19 percent of QSBS exclusions were claimed by households with non-QSBS incomes lower than $1 million (although typically more than $400,000), but the exclusion itself was worth more than $1 million. Taken together, 94 percent of QSBS exclusions are claimed by households where their non-QSBS income, combined with the money they received from their sale of qualified stock, exceeds $1 million. Very few U.S. households, fewer than 0.5 percent of all tax filers, have incomes at this level. That makes this tax carveout even more concentrated among the very wealthy than capital gains realizations more generally.

Figure 1

These new data, however, failed to deter Congress from expanding QSBS further in the tax and spending law enacted in July 2025. The new law increases the amount of capital gain on an investment that each investor can shield from tax, shortens the time investors must hold onto the stock before selling, and increases the asset size of eligible corporations, meaning that even larger investments and larger corporations can now participate, and can do so quicker.

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the expansion of QSBS will cost the federal government $3.5 billion in 2031 and $4.5 billion in 2034. These figures imply expansions of QSBS exclusions equal to 1.1 percent of capital gains in 2031 and 1.3 percent of capital gains in 2034, respectively. These bring the total amount of excluded gains under the program to 2.9 percent of capital gains in 2031 and 3.1 percent in 2034 — a roughly 12-fold increase since the early 2010s.

QSBS is a policy designed to further enrich the wealthy

One reason QSBS exclusions are so skewed to the wealthy is that beneficiaries must meet a slate of requirements that most ordinary small business owners and Americans investing for retirement will never meet. There are stipulations around which businesses qualify for investing in under the program, what stocks from a qualifying business are eligible for the benefit, and how much an individual can claim. Wealthy investors have built these criteria into their strategic planning so that when they win big on a successful investment, they don’t have to pay a cent of income tax on it.

An investor is allowed to pay zero taxes on their investment returns up to 10 times their initial investment or up to $15 million dollars, whichever is greater, for each eligible business they invest in. Prior to the new federal law’s passage, the dollar limit was $10 million. The qualifying stocks can be spread among family members if an investor is worried about bumping against their limit, allowing a tax-free option for bequeathing wealth during a wealthy person’s lifetime.

For an investment gain to qualify for QSBS, the investor must have held the investment for five or more years to pay no taxes, four years to pay taxes on only 25 percent of the gains, and three years to pay taxes on only 50 percent of their gains. The stock must be an original issuance from the company, and stock sold through intermediaries and exchanges are ineligible.

For example, a startup founder may pay themselves in company stock as they are building the business, or investors putting up capital for a startup or business expansion can do so in exchange for qualifying stocks, and both would be able to take advantage of the QSBS tax exclusion. By contrast, a person investing their IRA in a small capital fund that prioritizes small, high-growth companies would not benefit from QSBS because the stock is not issued directly by the company.

Businesses that can issue QSBS eligible stocks must be C corporations, have gross assets under $75 million at all times leading up to issuing the stock (the asset limit was $50 million until this year), and not fall into a number of trades and industries that are barred from the benefit (see box).

These rules generally exclude most small businesses. Most small businesses organize themselves as Limited Liability Companies or similar pass-through entities, not as C Corporations. By contrast, companies organize themselves as C corporations only if they are trying to attract venture capital investments and/or eventually become publicly held. Nor is a business with $75 million in assets necessarily “small” under any standard definition.

C corporation status has been in decline as more businesses have chosen to structure themselves as LLCs and S corporations; fewer than 5 percent of businesses now choose to incorporate with this status. The vast majority of small businesses do not choose a C corporation structure, meaning most small business owners will not benefit from this tax break, and the additional restrictions on trade and industry further restrict the universe of eligible business owners.

What Types of Investments Are Ineligible for QSBS Exclusion?

Investments in some businesses are ineligible for the QSBS exclusion. Ineligible investments, according to the Internal Revenue Code, include:

(A) any trade or business involving the performance of services in the fields of health, law, engineering, architecture, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees;

(B) any banking, insurance, financing, leasing, investing, or similar business;

(C) any farming business (including the business of raising or harvesting trees);

(D) any business involving the production or extraction of products of a character with respect to which a deduction is allowable under [IRC] section 613 or 613A [involving oil and gas extraction]; and

(E) any business of operating a hotel, motel, restaurant, or similar business.

States overlooked QSBS for many years, but the stakes are too high now to ignore

Thirty-eight states plus the District of Columbia are losing revenue due to QSBS. They include:

- 36 states plus the District of Columbia that tax most capital gains realizations through their income taxes but allow the full QSBS exclusion;

- Hawai’i, which allows a 50 percent QSBS exclusion; and

- Washington, which has no income tax but levies a capital gains excise tax that includes a QSBS exclusion.

Alabama, California, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania have income taxes but do not allow the QSBS exclusion. The remaining eight states have no income tax.

Figure 2

Appendix A.1 provides estimates of the cost of the QSBS exclusion to the 38 states that allow it. The estimates for 2026 are based on the total QSBS exclusions reported in the Treasury study, prorated to each state based on its share of national capital gains realizations as reported by the IRS, and converted into revenue loss based on the typical investor’s marginal tax rate – in most states, the top income tax rate. More on our methods can be found in Appendix B.

Appendix A.2 shows how the revenue loss is expected to grow. By 2031, when the changes enacted in 2025 have taken full effect, states conforming to QSBS and its expansions will experience a 70 percent increase in the cost of conforming to the program. Decoupling from the recent expansion in all states would raise $470 million in 2031, whereas decoupling from the QSBS exclusion all together would raise $1.2 billion.

Figure 3

A quirk in the newly enacted expansion may lead some states to view QSBS conformity as a short-term revenue raiser, but the revenue is small – and represents only a 1 percent reduction in exclusions in 2026. Much more important is that by 2031, conformity to the expansion will swell the program cost by two thirds relative to conformity to pre-2025 rules. For states interested in preserving revenues, decoupling entirely from the QSBS is a better way to approach the conformity problem, because – as these state-by-state estimates show – it will preserve significant revenue in the short term and even more in the long term, and be simpler to administer.

QSBS is a poor strategy for boosting small businesses or state economies

Some states may be tempted to retain the QSBS exemption on economic development grounds, perhaps imagining that the “small business” allusion in the name of the tax break is based on something reasonable. In fact, most truly small businesses cannot access the benefits of QSBS investments. That’s because QSBS is only available to C Corporations, while most small businesses – those that are structured as partnerships, LLCs, S corporations, or sole proprietorships – are barred from benefiting. A 2021 investigation identified investments in big corporations like Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Zoom, Pinterest, and DoorDash as benefiting from of the exemption. Investors receiving the tax break have included partners in mammoth investment firms like Andreessen Horowitz, the investigation found.

At a national level, QSBS is turning out to be an ineffective way to support investment in emerging companies. As the Washington Center for Equitable Growth wrote in a recent review:

The original intent of the QSBS exclusion was to encourage investment in small businesses that might otherwise have difficulty attracting capital. Limited research suggests that the exclusion results in a modest increase in early-stage funding but at a relatively high cost. ….

The dramatic expansion of the venture capital sector in recent years draws into question whether the conditions that led to the enactment of the exclusion still apply today. Some researchers argue that there is now a “glut” of venture capital available and that investable funds exceed quality investments. These critics charge that the QSBS exclusion provides a costly windfall that narrowly benefits extraordinarily wealthy investors.

Even if QSBS were an effective strategy at the national level, it wouldn’t be so at the state level. That’s because QSBS investments don’t have to be in-state to qualify for the state tax break, and venture capital firms regularly invest across state lines. A Georgia-based venture capitalist, for example, might claim QSBS exemptions on her investments in startups anywhere in the U.S., reducing revenue for the state treasury but providing no guarantee of economic benefit to Georgia.

States seeking to accelerate investment in startup companies have much better tools at their disposal than QSBS. They range from investing in STEM education and research universities to strengthening their infrastructure to supporting community loan funds. Studies consistently show that factors like talent availability, university partnerships, and infrastructure quality matter far more than tax rates for innovation-based economic development.

California provides an instructive example of an alternative path forward. California enacted a set of rules in 2008 for the QSBS exemption that allowed California-based investors to claim the exemption on their state income tax returns only for investments that created in-state jobs. A court ruled in 2012 that those rules were discriminatory under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. So California did away with the exemption altogether.

The state’s decision to abandon the QSBS exemption does not appear to have harmed Californians’ willingness to provide venture capital for startups. California remains the nation’s biggest source of venture capital dollars as well as the state with the largest number of venture-capital investments.

Although the state eliminated QSBS benefits in 2013 and taxes capital gains through its personal income tax at rates up to 13.3 percent, California companies still attract more venture capital investment than the rest of the country put together, California-based venture capital funds raise more than three times as much money as those in the next highest state (New York), and California taxpayers report more capital gains than anywhere else. The California example should provide reassurance that a state decoupling from the federal QSBS exemption will not harm its attractiveness to venture capital.

Decoupling from QSBS as a tax fairness strategy

Decoupling from the QSBS exemption can be a part of a broader strategy to improve how states tax income from wealth. The QSBS exemption is only one of the ways that states extend favorable tax treatment to capital gains. States don’t tax capital gains until they are realized, that is, until an asset is actually sold. And if an asset is never sold but rather bequeathed as part of an estate, it may never be taxed. The result is that ordinary wage income is taxed at a higher level than income from wealth.

To address these broader issues, some states are enacting or considering new taxes on capital gains income or investment income more broadly. Minnesota in 2023 enacted a Net Investment Income Tax (also called a Wealth Proceeds Tax), while Maryland enacted a surcharge on capital gains realizations in 2025. Other states have considered similar measures, and New York and California have clamped down on their wealthy residents avoiding taxes through sheltering income in tax haven states.

Broader taxes on investment income and other measures aimed at asking more of wealthy households, including sensible policies to prevent tax avoidance by the wealthy and corporations, are likely to raise much more revenue than repealing the QSBS exemption. In this context, QSBS decoupling should be seen as one part of a broader strategy to improve state tax treatment of income from wealth and bolster state services.

Appendix B: Methods

To estimate the revenue states could preserve by eliminating the QSBS exclusion, we first develop a projection of nationwide federal QSBS exclusions for 2026 and 2031, setting aside for the moment the expansions to the program enacted in the 2025 federal tax law.

We project a base for our estimates using data from the U.S. Treasury on QSBS exclusions as a percent of total net capital gains, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projection of capital gains realizations projections. Full QSBS exclusions, equal to 100 percent of the gain, became available for the first time for shares sold in September 2015, so we use the average of 2016 to 2022 data from the Treasury, expressed as a share of net capital gains, to project QSBS exclusions for 2026 and 2031 using the CBO forecast.

Given that CBO’s projection for growth in capital gains is relatively flat for these years, so too are our QSBS projections. These calculations produce estimates of nationwide pre-OBBB QSBS exclusions of $31.6 billion and $33.2 billion for 2026 and 2036, respectively.

Separately, we calculate the additional QSBS-eligible realizations anticipated under the 2025 expansion.

To do this, we use the U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimate of the increase in QSBS cost under the new law and divide it by the marginal federal capital gains rate (which CBO estimates is 21.2 percent) to compute the change in QSBS realizations.

For 2026, the JCT score shows a trivial federal revenue gain from the QSBS change equal to approximately 1 percent of the total size of the previous QSBS program. The cause of this gain is not apparent in the legislation, and it is not clear whether this is a direct result of changes in the expected volume of stock sales categorized as QSBS, or whether it is attributable to an indirect behavioral effect. Given this uncertainty, its distribution across states is highly speculative and potentially even subject to variation in direction. We therefore do not include this minor effect in our estimates.

Figure 4

Next, we share these realizations down to states based on their share of national capital gains.

Each of these estimates is shared down to states using data found in IRS SOI Historic Table 2 (HT2) for Tax Year 2022. While HT2 does not report data specific to QSBS, it does contain data on overall realized capital gains by state, which we use as a proxy to distribute the tax savings associated with the QSBS capital gains carveout. HT2 includes all returns filed and processed through the IRS’ Individual Master File system. Because the large majority (82 percent) of QSBS exclusion claims are made by individuals, the population of return filings covered in HT2 includes the bulk of all returns that can be expected to make QSBS claims. The remaining 18 percent of QSBS claims are by trusts and estates and, in the absence of up-to-date IRS data on the size of these filings by state, we assume that this portion of QSBS claims is distributed across states in the same manner as the individual claims.

Then we estimate state and local income tax revenues from decoupling from QSBS.

To estimate the net change in state and local revenues from decoupling from federal QSBS exclusions, we use an equation preferred by CRS as described in its detailed review of empirical studies of investor responses to changes in capital gains taxes. The equation is used to estimate revenue impacts of changes to capital gains tax rates, accounting for behavioral responses and current combined federal, state, and local marginal capital gains tax rates on QSBS realizations in each state. We use a realization coefficient of 2.28, which is the midpoint of the coefficients found in CRS’ review of the economic literature. This adjustment produces nationwide revenue estimates 18 percent lower than a static revenue estimate that does not account for behavioral responses to the tax rate, but individual states range in their behavioral response.

For calculating the revenue raised by taxing QSBS, we typically use the top state and local income tax rates as the marginal rate, as the overwhelming majority of QSBS claimants have QSBS-inclusive incomes high enough to subject them to states’ top tax brackets. In New York state, where the top rate applies at a much higher taxable income level than in other states, we apply the second highest bracket rate in calculating the revenue effect. In Washington, which levies a narrow tax only on capital gains with a large standard deduction and progressive bracket structure, we calculate and apply an effective tax rate of 8.5 percent based on our analysis of the Treasury Department’s distributional data for QSBS. In states with local taxes on capital gains, we then separate our revenue estimates into state and local shares using the share of the rate change that each represents.

Note: This brief was updated in January 2026 to reflect revisions to revenue estimates in Ohio and Washington, which in turn slightly affected the national results.