Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

Most of us don’t need to be reminded about inflation. We experience it every day, as the price of the goods and services we buy gradually goes up over time. As the cost of living goes up, our incomes generally go up too, partially because of inflation. But many state tax systems are not designed to take account of inflation. The result is that income taxes often grow faster than incomes—even though lawmakers haven’t actually passed any laws to make this happen. Some lawmakers have responded to this “hidden tax hike” by indexing their income taxes for inflation. This policy brief explains how indexing works and evaluates its impact on tax adequacy and fairness.

How Inflation Affects Income Taxes

Many features of state tax systems are defined by fixed dollar amounts. For instance, personal income taxes usually have various tax rates starting at different income levels. If these fixed income levels aren’t adjusted periodically, taxes can go up substantially simply because of inflation. This hidden tax hike is popularly known as “bracket creep.”

Many features of state tax systems are defined by fixed dollar amounts. For instance, personal income taxes usually have various tax rates starting at different income levels. If these fixed income levels aren’t adjusted periodically, taxes can go up substantially simply because of inflation. This hidden tax hike is popularly known as “bracket creep.”

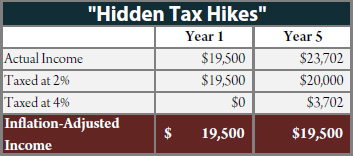

Take, for example, a hypothetical state that taxes the first $20,000 of income at 2 percent and all income above $20,000 at 4 percent. A person who makes $19,500 will only pay tax at the 2 percent tax rate. But over time, if this person’s salary grows at the rate of inflation, she will find herself paying at a higher rate—even though she’s not any richer in real terms. In this example, suppose the rate of inflation is five percent a year and the person gets salary raises that are exactly enough to keep up with inflation. After four years, that means a raise to $23,702 (that’s a 5 percent a year raise from $19,500). Now part of this person’s income will be in the higher 4 percent bracket—even though, in terms of the cost of living and ability to pay, her income hasn’t gone up at all.

Adding It Up: The Impact on Tax Fairness

Of course, the problem of “bracket creep” is not limited to tax brackets. Any feature of an income tax that is based on a fixed dollar amount will have inflationary effects. In many states, this means that tax breaks designed to provide low-income tax relief—including exemptions, standard deductions, and most tax credits—are worth a little bit less to taxpayers every year. When all these small impacts are added up, the long-term effect can be a substantial tax hike—and one that falls hardest on low- and middle-income taxpayers.

For example, when the Illinois income tax was adopted in 1969, the state’s personal exemption was set at $1,000—and was subsequently left unchanged for thirty years. 1998 legislation doubled the exemption to $2,000—but if the exemption had kept up with inflation since 1969, it would have been worth $5,800 in 2010. In other words, the Illinois personal exemption is worth $3,800 less than it originally was. As a result, Illinois taxpayers paid about $1.5 billion more in income taxes in 2010 than they would have if the exemptions had been adjusted to preserve their 1969 value. Of course, Illinois lawmakers never voted to enact such a regressive tax hike—but this tax hike is the direct consequence of not indexing for inflation.

In general, inflationary tax hikes hit middle- and low-income families more heavily than wealthy people because most of wealthier taxpayers’ income is already taxed at the top marginal tax rate. For someone making $200,000 a year, five years of five percent inflation in an income tax without indexed tax brackets in the example on the previous page would hardly change his or her effective tax rate at all.

Indexation: How it Works

The way the federal personal income tax code and some state income tax structures deal with these hidden tax hikes is by “indexing” tax brackets for inflation. In the example on the previous page, indexing for inflation would mean that the $20,000 cutoff for the 4 percent tax bracket would be automatically increased every year by the amount of inflation. If inflation is five percent, the cutoff would automatically increase to $21,000 after one year. After four years (of five percent inflation), the 4 percent bracket would start at $24,310. So, when the person in our example makes $23,702 after four years, he or she would still be in the 2 percent tax bracket. In other words, indexing income taxes for inflation helps ensure that the tax system treats people in roughly the same way from year to year.

Conforming to Federal Tax Rules Can Help

Most features of the federal income tax are already indexed for inflation. This means that states that tie their income taxes closely to federal rules will find it easier to avoid inflationary tax hikes. For example, Arizona’s low-income tax credit is not indexed for inflation. But the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is inflation-adjusted. So if Arizona replaced its low-income credit with a state EITC based on federal rules, the problem of inflationary tax hikes would be partially solved. Conforming to federal personal exemptions and standard deductions would help achieve this, too.

Inflation Affects Other Taxes

The personal income tax is not the only tax affected by inflation: property taxes are equally susceptible to hidden tax hikes. Property tax circuit breakers usually work just like personal income tax credits. If your property taxes exceed a certain percentage of income than a circuit breaker property tax credit is given to offset property taxes paid.

For example, if the Illinois circuit breaker’s maximum income level for eligibility and the maximum credit amount had been indexed for inflation since it was first introduced in 1972, the income threshold would have been $52,000 in tax year 2010—more than double the current value for unmarried taxpayers—and the maximum value of the credit would have been about five times its current value. The impact of inflation, combined with the rapid growth of property values, means that the circuit breaker in states like Illinois becomes less effective as a property tax relief tool every year.

Should States Index?

Inflationary tax hikes do have one advantage for policymakers because they are basically invisible to taxpayers, they are much easier to enact than explicit tax hikes. But in practice, inflationary tax hikes aren’t a good tax policy strategy. It’s hard to know the impact of inflationary tax hikes ahead of time, and these hidden tax hikes usually fall most heavily on low- and middle-income taxpayers. “Invisible” tax hikes make the tax system harder to understand, and few lawmakers would choose to balance state budgets by imposing this sort of tax hike. Indexing tax systems for inflation allows lawmakers to create the income tax structure they want—and to ensure that the impact of the income tax on taxpayers at different income levels will only change when they want it to.