Child Tax Credit Enhancements Under the American Rescue Plan

reportNational and state-by-state data available for download

Key Points:President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit provision would:

|

Overview

President Joe Biden’s recently unveiled coronavirus relief package, the American Rescue Plan, includes a significant expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The president’s proposal provides a $125 billion boost in funding for the program, which would essentially double the size of the existing federal credit for households with children.

The proposal makes two significant changes. First, it would increase the maximum credit from $2,000 to $3,000 with an additional $600 for each child under the age of six.[1] Second, it would make the CTC fully refundable by removing a rule limiting the refundable portion to $1,400 and by removing the earnings requirement (the current rules limit the refundable portion of the credit to a percentage of earned income in excess of $2,500). These changes not only put more money in families’ pockets, they extend the credit to children who are left behind by the current credit.

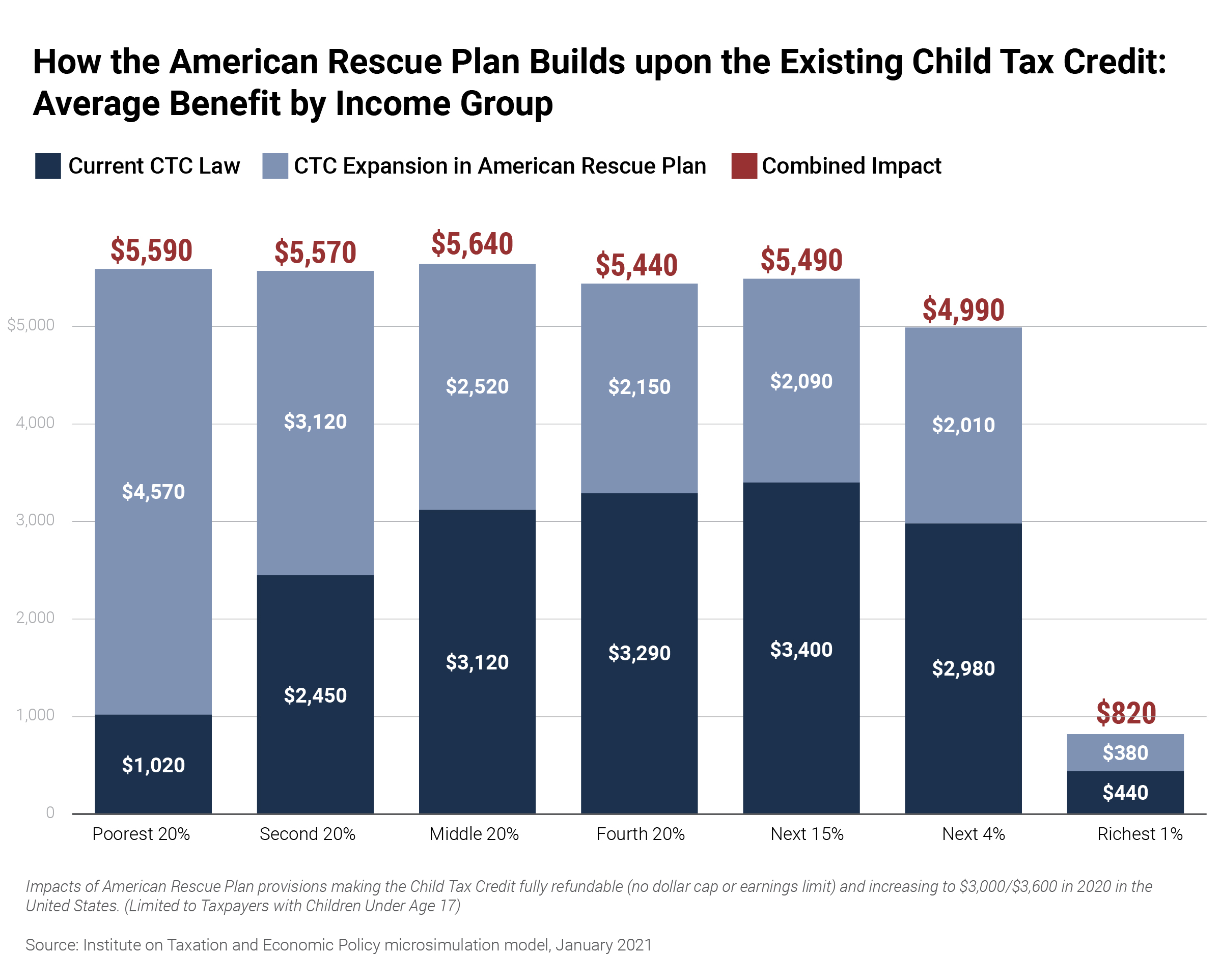

Roughly 83 million children live in households that would benefit.[2] Families with children would receive an average of $2,750, with the biggest boost (an average of $4,570) going to low-income families. The proposal would lift the incomes of families with children who make $21,300 a year or less (the poorest 20 percent) by 37.4 percent, a dramatic increase for those families most in need. Further, some versions of the proposal would send automatic monthly payments to families with children—a meaningful step that would more immediately get cash in families’ pockets.

These proposed changes would allow the credit to reach more children of all races. For tax filers and their families among the poorest 20 percent, virtually no child receives the full credit because their parents earn too little. More than a third of all white children, more than 45 percent of Hispanic children, and nearly half of Black children are in families who do not receive the full credit.[3]

The move toward full refundability, without an earnings requirement, would fix the serious shortcoming that allows only a partial benefit or no benefit for many low-income families. Simply boosting the credit value, by contrast, is not as targeted and would provide more sweeping tax cuts to families throughout most of the income distribution as the credit does not begin to phase out until income reaches $400,000 a year for married parents and guardians (or $200,000 for single parents and guardians).

But together these credit enhancements would provide broad benefits to families with children not just across the income distribution, but across races and ethnicities as well.

Roughly 99 percent of tax filers with children would benefit. Because families of color are more likely to have children under 17, they are more likely to benefit. More than one in four (28 percent) of all tax filers and their families would benefit from this package of CTC reforms. This includes 40 percent of Hispanic households, 32 percent of Asian households, 31 percent of Black households, and 25 percent of white households.[4]

As shown in the table below, the average amount of the CTC for families with children under age 17 would be modest and relatively consistent across race and ethnic groups. But Black and Hispanic tax filers with children have smaller average incomes (due to longstanding structural inequities in access to education, jobs and wealth building), which means that the proposal provides them with a slightly larger benefit as a share of their income. The proposal would increase the incomes of Black (by 3.4 percent) Hispanic (3.1 percent), white (2.2 percent) and Asian (1.8 percent) families with children.

While the provisions help all families with children, the benefit is much more meaningful for low-income families. The Child Tax Credit expansion in the American Rescue Plan would dramatically reduce child poverty by boosting the incomes of the lowest-income families by 37.4 percent. The Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University analyzed the poverty reduction potential of a select set of proposals under Biden’s American Rescue Plan. They found that the extension of SNAP benefits, the direct $1,400 payments, the extension of unemployment insurance expansions, and the CTC enhancements combined could cut child poverty in half in 2021.[5] The same researchers previously found that the CTC changes alone would lift more than 6 million children out of poverty and another study of the American Family Act, which is similar to Biden’s CTC proposal, predicted nearly a 45 percent reduction in poverty for families with children under 18. Poverty reductions would be even more dramatic, on average, for larger families and families of color. For example, while this plan would lift a sizable share of white children (43.4 percent) out of deep poverty—the share of kids living below half the poverty threshold or less—it would lift more than half of Black and Hispanic children (54 and 52 percent, respectively) out of deep poverty.[6]

The Importance of Full Refundability

Today’s federal Child Tax Credit provides up to $2,000 per child. However, most low- and moderate-income families do not receive the full benefit due to the current earnings requirement and lack of full refundability for families with low incomes. Children with parents or guardians who have less than $2,500 in earnings are generally ineligible for any federal CTC. For families above this earnings requirement, the refundable portion of the federal CTC is limited to 15 percent of each dollar of earnings over $2,500. The refundable portion of the CTC is also limited to a smaller amount, just $1,400 per child.

As a result of the limitations confronting lower- and moderate-income families, more than one-third (39 percent or roughly 33 million) of all children live in families with earnings too low to qualify for the full CTC.[7] That statistic is even more pronounced when broken out by race and ethnicity. Nearly half of all Black children (47.6 percent) and a similar share of Hispanic children (45.7 percent) are not currently receiving the full benefit of the federal credit. That share is somewhat lower for white children, at 36 percent, but still far too high.

Making the Child Tax Credit fully refundable is key to ensuring that children in low-income families can receive the full benefit of the federal credit and would meaningfully increase the after-tax incomes of those who are currently left behind. If a credit is refundable, taxpayers receive a refund for the portion of the credit that exceeds their income tax bill. Refundable credits therefore can be used to help offset the cost of all types of taxes, including payroll taxes and state and local taxes, rather than just federal income taxes. These types of credits can also serve as a valuable cash infusion, bringing a measure of financial stability to cash-strapped families.

Full refundability is uniquely targeted to low-income families and is key to allowing the CTC to move the needle on the stubbornly high rate of child poverty in the United States.

While the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) increased the federal CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 per child, it continued to limit the refundable portion of the credit by 1) limiting it as a percentage of earnings, not counting the first $2,500, and by 2) subjecting the refundable portion of the CTC to a dollar cap, set at $1,400 in 2020. As a result, families with very low earnings—arguably those most in need of the benefit—do not receive the credit or receive only a partial credit.

As the graph below indicates, implementing full refundability with no earnings limit would offer major benefits to the bottom 20 percent of tax filers and their families, who have incomes of less than $21,300 a year. Nearly all of these families (about 99 percent) are too poor under current law to receive the full benefit of the credit. Well over half of the benefit of full refundability goes to those in the bottom 20 percent. These changes alone boost the incomes for families with eligible children earning less than $21,300 a year by 19.6 percent.

In contrast, the impact of just increasing the credit from $2,000 to $3,600 for children six and under and to $3,000 for older children without addressing the shortcomings of the existing credit would do nothing for this lowest-income group. That is, a larger credit amount will not reach the families most in need unless full refundability is also enacted. Absent that change, the largest tax benefits from an expanded CTC would go to families in the top 20 percent of the income distribution who earn six-figure incomes but not quite enough to find themselves in the CTC’s phase-out range (which starts at income of $400,000 for married couples and $200,000 for single taxpayers).

But together, these components of the proposal (making the credit fully refundable and increasing the credit amount) greatly benefit the nation’s lowest-income children and families, boosting their average benefit from just over $1,000 to $5,590. The proposal also provides a sizable tax benefit to families across the income scale, as illustrated in the following figure. For the poor, the impact of this proposal is greater than the sum of its parts. The increase in the credit amount interacts with the reforms that make the credit fully refundable to deliver a much larger benefit to those who need it most.

This highlights the value and necessity of implementing full refundability to correct for the shortfalls of the federal credit and to target children living in households of the lowest-income individuals and families. Without this key reform, policy adjustments would perpetuate the inequities currently built into the current design of the federal Child Tax Credit.

While the benefits of the CTC should arguably be even more precisely targeted toward lower- and middle-income households, the combined result of these policy changes is progressive in its impact and therefore would slightly narrow the nation’s yawning income gap while also making a sizable dent in child poverty.

[1] For this group, income is thought to be more consequential for children’s early development and parents of young children often earn less. See endnote 3.

[2] Our analysis includes children in households directly benefiting from the CTC enhancement and other child dependents in the household who are too old to receive the credit but live in a household with a child that qualifies.

[3] Wamhoff, Steve. “New ITEP Estimates on Biden’s Proposal to Expand the Child Tax Credit.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 18, 2020. https://itep.org/new-itep-estimates-on-bidens-proposal-to-expand-the-child-tax-credit/

[4] With the exception of this statistic, which provides the overall impact of the federal Child Tax Credit on the broader population, this analysis is focused on families with children under 17 years of age. The CTC component of Biden’s American Revenue Plan extends the credit to 17 year olds, but this analysis does not incorporate that change.

[5] Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University. January 14, 2021. “The Potential Poverty Reduction Effect of President-Elect Biden’s Economic Relief Proposal.” Poverty and Social Policy Fact Sheet. https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/2021/presidential-policy/biden-economic-relief-proposal-poverty-impact

[6] Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University. 2021. “A Poverty Reduction Analysis of the American Family Act.” Poverty and Social Policy Fact Sheet. https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/2019/3/5/the-afa-and-child-poverty. The report includes 50-state data.

[7] Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University. May 13, 2019. “One-Third of Children in Families Who Earn Too Little to Get the Full Child Tax Credit.” Poverty & Social Policy Brief, Vol. 3 No. 6. https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/leftoutofctc