At a House Ways and Means subcommittee hearing Wednesday on “global competitiveness for American workers and businesses,” Republican members insisted that President Trump’s tariff policies were not relevant to the topic at hand and instead focused on the unpopular tax laws they enacted in 2017 and this summer.

Democrats on the subcommittee asked witnesses point blank whether Trump’s tariffs would affect international commerce and American businesses. Kevin Brady, a Republican former member of Congress called to testify at the hearing, refused to answer the question.

Rep. Jimmy Gomez read several quotes from Brady during his time in Congress stating that tariffs are taxes that impede economic growth. Brady, who chaired the Ways and Means Committee and drafted Trump’s first tax law in 2017 (and now works as a lobbyist), had no desire to discuss those quotes or the topic of tariffs.

Perhaps this is not surprising because recent polling shows that Trump’s tariffs are even more unpopular (61 percent disapprove vs. 38 percent approve) than the new tax and spending law (46 percent disapprove vs. 32 percent approve).

It is also unsurprising that Republicans do not want to debate how Trump’s tariffs are increasing prices for Americans a day after Trump publicly said that affordability is a “false narrative” and a “con job” that “doesn’t mean anything to anybody.”

Nor did Republicans address the point made by the Democrats’ witness, Kimberly Clausing, when she explained that Trump’s tariffs are the biggest tax increase on Americans (measured as a share of the economy) since 1982.

In theory, tariffs could be a small part of a broader set of tools that are used surgically to address narrow problems in trade policy, but that has nothing to do with how Trump is using tariffs.

He recently even claimed that the personal income tax could be replaced entirely by tariffs. This is impossible because most of the tax increase imposed on Americans by tariffs takes the form of increased prices rather than actual revenue collected from them. Even Trump’s expanded tariffs collected just $195 billion in the recently ended fiscal year and would never raise more than around $370 billion according to Clausing’s calculations, which is nowhere near the $3 to $4 trillion collected every year in individual income taxes.

So, Republicans chose to focus instead on the tax laws they enacted during the first and second Trump administrations. This required them to make claims about the impacts of their tax policies that are at best misleading, and at worst simply untrue. Here are a few examples.

The tax laws enacted by Trump have not made Americans businesses more competitive; they have simply cut their taxes

In 2017, Trump and his Congressional allies argued that the existing tax code put American corporations at a competitive disadvantage that could only be resolved with tax cuts. This was not true. Prior to enactment of the first Trump tax law in 2017, U.S. corporations already had a massive competitive advantage in the global economy. That advantage remains virtually unchanged today.

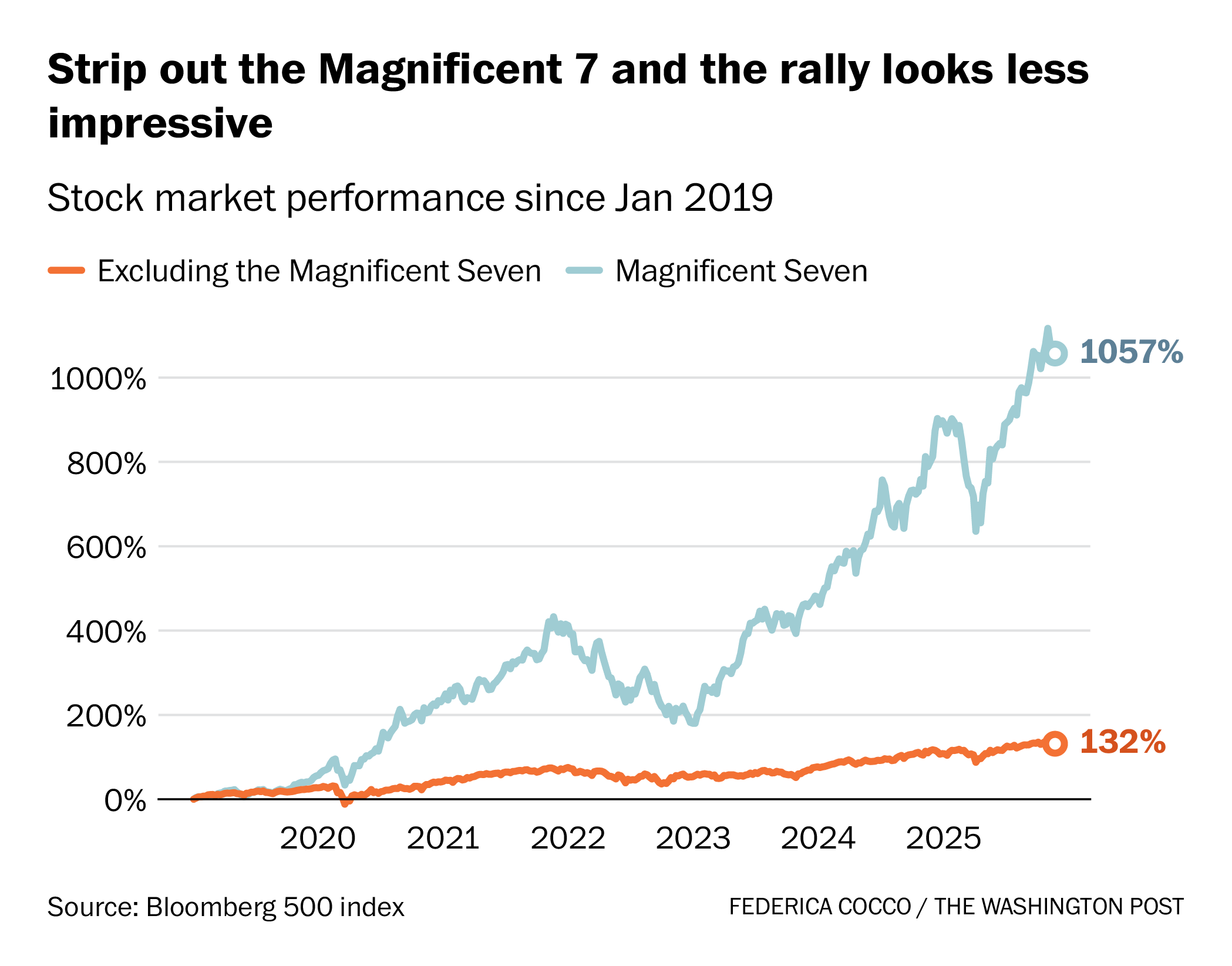

Nearly all the growth in the U.S. stock market in recent years has been due to seven huge tech companies: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla. These are often called the “Magnificent Seven” and their growth stems from surging investments in AI.

It is not clear that the AI boom has anything to do with tax policy, and in fact, it began in late 2022 when the 2017 law made the tax treatment of research and investment less generous.

Outside these seven corporations there has not been much growth for U.S. companies. As one analysis recently explained, “An index that leaves out the seven high-flying tech firms — call it the S&P 493 — reveals a far weaker picture, as smaller and lower-tech companies report lackluster sales and declining investment.”

The U.S. accounts for just over 4 percent of the world’s population but its share of the corporations among Forbes Global 2000 publicly traded companies has always vastly exceeded that.

American corporations outside the Magnificent Seven accounted for 33 percent of the total profits reported by the Forbes Global 2000 in 2017, before the first Trump tax was enacted, and are estimated to account for 32 percent of those profits this year. (These figures are 37 percent in 2017 and 43 percent for this year if we include the Magnificent Seven and their AI-driven surge.)

American corporations outside the Magnificent Seven accounted for 38 percent of the market value of the Global 2000 in 2017 and account for 39 percent today. (These figures are 44 percent for 2017 and 55 percent this year if we include the Magnificent Seven.)

There is simply no way to describe U.S. corporations as “uncompetitive” before the 2017 tax law was enacted and no evidence that they are more competitive today because of it.

Tax laws enacted by Trump did not address the problem of American corporations moving offshore

Before the 2017 Trump tax law was enacted, some American corporations used loopholes to characterize themselves as foreign corporations even though they were clearly American companies.

In these so-called “inversions,” an American corporation merges with or acquires/is acquired by a foreign company, and the resulting entity claims to be a foreign one and thus not subject to certain U.S. tax rules, even though it is majority owned by the same people or same parties who owned the American corporation, and there is usually no movement of the physical headquarters or management from the U.S.

There have been no inversions of American corporations after the 2017 law was enacted because that law simply gave multinational corporations everything they wanted in terms of tax cuts so that they no longer had the incentive to escape the U.S. tax system in the same way.

Republicans at the hearing described corporate inversions as situations where American corporations would move their headquarters and move capital offshore to avoid the U.S. tax rules. That is not true. Corporate inversions are reorganizations that exist on paper but do not fundamentally change who owns a corporation, which country it is managed from, or where it even does business. They allow corporations to avoid paying U.S. taxes because of loopholes that Congress has refused to close. The 2017 law simply allows corporations to pay little or nothing in U.S. taxes in different ways.

Trump’s tax laws do not primarily benefit regular American workers and families

Nothing discussed or debated at the hearing changed the basic fact that the Trump tax cuts are designed to almost entirely benefit the richest Americans. As ITEP research on the 2025 Trump tax law found this summer:

- More than 70 percent of the net tax cuts will go to the richest fifth of Americans in 2026, only 10 percent will go to the middle fifth of Americans, and less than 1 percent will go to the poorest fifth.

- The richest 5 percent alone will receive 45 percent of the net tax cuts next year.

- The richest 1 percent of Americans will receive a total of $1 trillion in tax cuts over the coming decade from the new law, which is more than the amount the legislation cuts from Medicaid.

- Compared to what would have happened if Congress simply extended all the tax provisions scheduled to expire at the end of this year, the new law raises taxes overall on the bottom 40 percent of Americans, mainly because Republicans chose not to extend tax credit provisions that make health insurance more affordable.

Congressional Republicans are clearly desperate to avoid discussing Trump’s tariffs if this is the accomplishment they would prefer to talk about.