The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted by President Trump and Congressional Republicans at the end of 2017, has caused quite a bit of confusion, and a recent “Fact Checker” column by the Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler does not help.

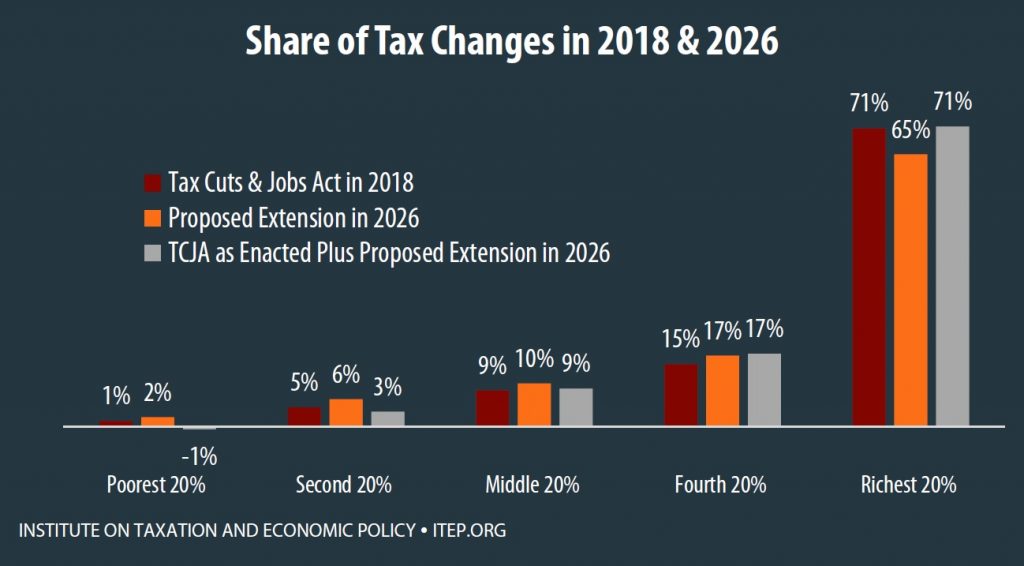

TCJA creates many problems, but two stand out. The first is its cost. Last year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that TCJA would reduce revenue by $1.9 trillion over a decade. The second problem is that most of the tax cuts go to high-income households who do not need them. Last year, ITEP estimated that TCJA would provide about half of its benefits to the richest 5 percent of Americans in tax year 2018. (About a fourth of the benefits would go to the richest 1 percent, and another fourth would go to the next richest 4 percent.)

These problems are serious and they will not be resolved until TCJA is replaced with a real tax reform that asks more of wealthy individuals and corporations.

Some lawmakers have described other problems with TCJA that are less grounded in fact. For example, Senator Kamala Harris tweeted that the average tax refund at this point in the filing season is lower than in the past and seemed to suggest that this was evidence that TCJA hiked taxes on the middle-class.

Harris is not alone in jumping to this conclusion. A recent flurry of media stories has spotlighted the fact that tax refunds during the first few days of this filing season were slightly smaller than last year. For families without adequate savings, a reduced refund or a surprise tax bill can create real financial difficulties. Unfortunately, Kessler glosses over this point. But he otherwise does an adequate job explaining the many factors that impact tax refunds and why a smaller refund is not the same thing as a tax increase. ITEP estimated that in tax year 2018, 84 percent of taxpayers would receive tax cuts and just 7 percent would see tax hikes as a result of TCJA. Looking at just the bottom two-thirds of taxpayers, 81 percent would receive a tax cut and just 5 percent would face a tax hike.

Kessler’s critique goes off the rails, however, when he attempts to dispute Sen. Harris’s factually accurate critique that the tax bill “line(s) the pockets of already wealthy corporations and the 1%.” According to ITEP’s estimates, which are generally inline with those of other organizations, the top 1 percent of earners received an average tax cut equal to 2.6 percent of their income in 2018, or $48,320 per household. In the middle of the income distribution, the cut was just 1.6 percent of income, or $810. And at the bottom, tax cuts under the TCJA averaged just 0.9 percent of income, or $120. For a low-income family, that works out to a boost in income of about $2.31 per week.

This is the type of analysis that Kessler should have used when evaluating Sen. Harris’s tweet. Instead, his “Fact Checker” column cherry-picks statistics to make the unbelievable suggestion that TCJA does not disproportionately benefit the rich.

Kessler argues that “any broad-based tax cut is going to mostly benefit the wealthy because they already pay a large share of income taxes” and cites a Cato Institute analyst who argues that fairness is best represented by measuring tax changes as a share of tax liability, which, depending on which taxes you include in the denominator, will create the illusion that TCJA’s tax cuts are not larger for the rich.

But there is widespread agreement among tax analysts that measuring tax changes relative to a taxpayer’s income–rather than tax liability–is a superior measure of progressivity. The Cato analyst’s suggested metric, around which Kessler builds much of his piece, isn’t just controversial among centrist or progressive commentators. Even the right-leaning Tax Foundation has made clear that it believes measuring tax changes relative to income is preferable. And as the ITEP analysis described above indicated, high-income households did indeed receive the largest tax cuts relative to their incomes.

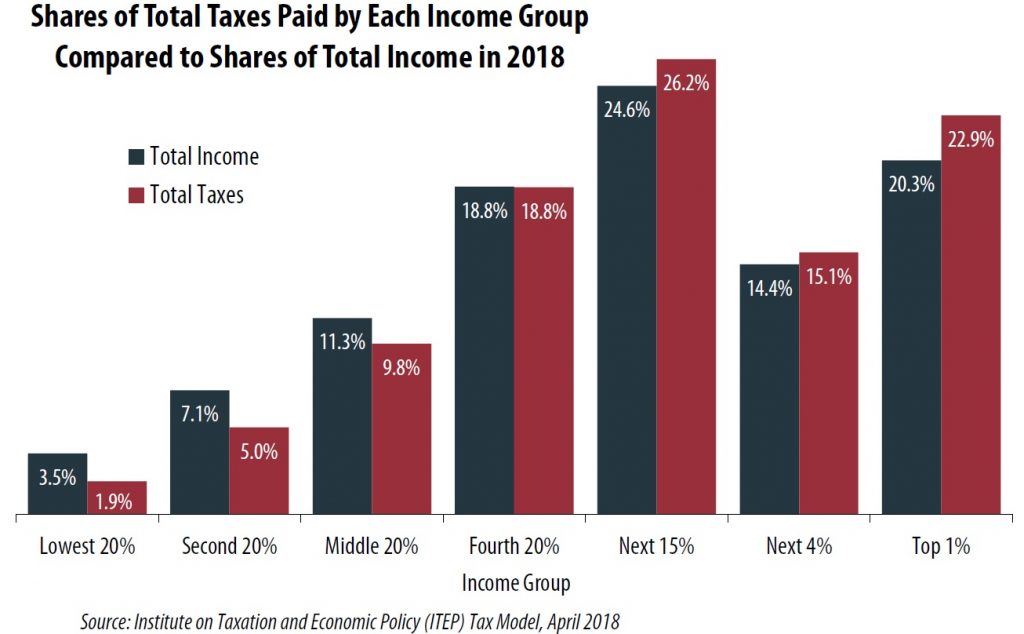

Kessler’s column also includes a heavy emphasis on the fact that income tax dollars, unsurprisingly, often come from people with large incomes. But he ignores the fact that the rich do not pay a significantly disproportionate share of taxes when America’s tax system is viewed as a whole. Last year, ITEP analyzed the total taxes (total federal, state and local taxes) people pay in the U.S. We found that the richest 1 percent received a little more than 20 percent of the total income in America and paid 23 percent of the total taxes. So, it is true that the richest 1 percent paid a share of taxes that exceeded their share of income (23 percent v. 20 percent) but not by very much. In other words, our tax system is just barely progressive.

Most people intuitively sense that the very richest households should pay more as a share of their income than other households. This is not an irrational belief. The public investments funded by tax dollars arguably benefit the rich more than anyone else. To take just one example, public roads built with tax dollars benefit everyone, but they benefit Jeff Bezos more than the average person because they have allowed him to make a fortune shipping products. The people who reap the largest rewards from the stability our public institutions and services help foster should be asked to contribute more to maintain those services.

TCJA created real problems that will never be resolved until it is replaced by a real tax reform. To begin that process fact checkers, lawmakers, and everyone else need to be clear about what TCJA did, and did not, do to our tax system.