Key Findings

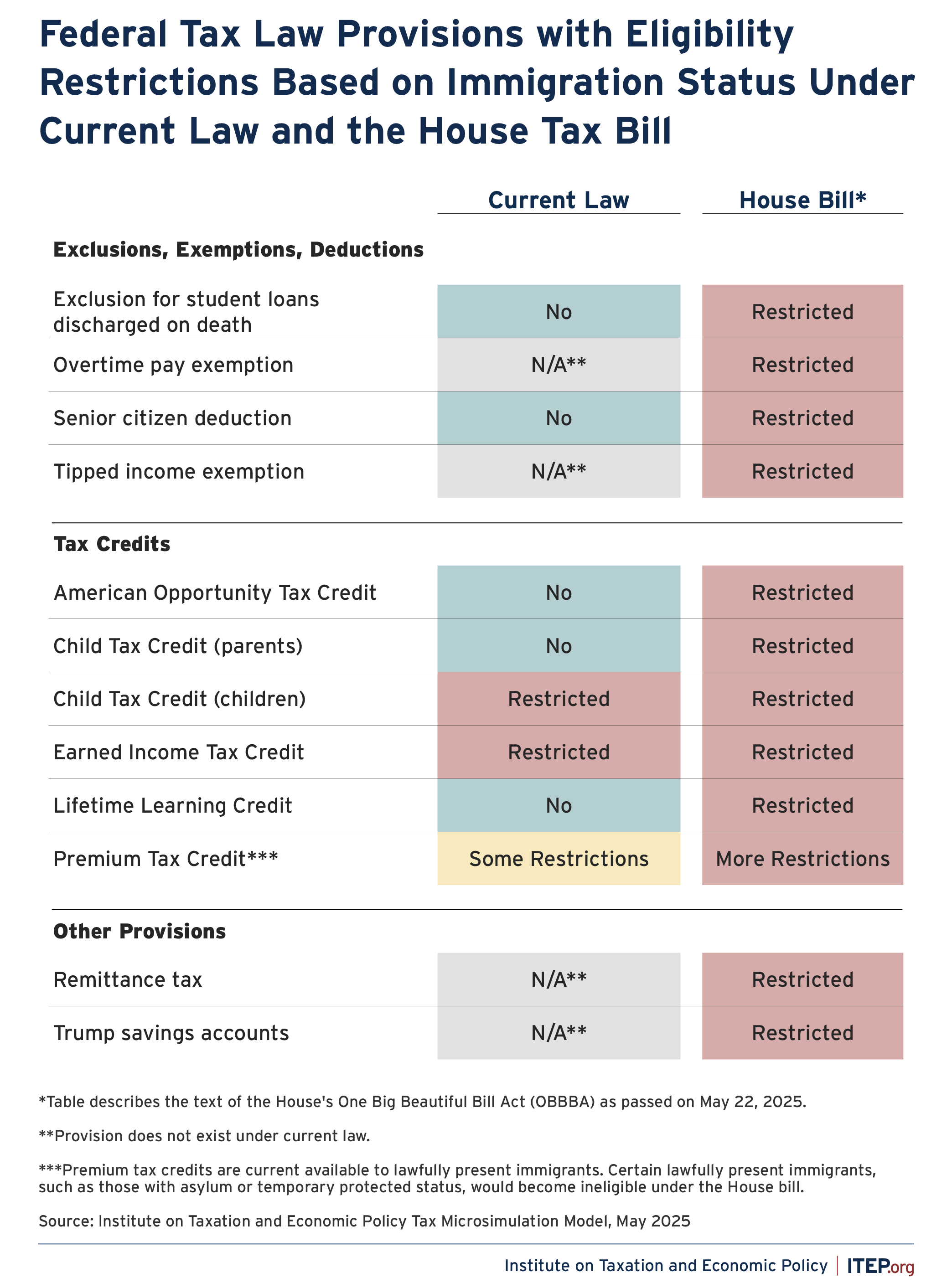

- The vast majority of the federal tax code applies to citizens and immigrants alike, though immigrant tax filers do face a harsher tax code than citizens in some notable respects. Specifically, at least some immigrant tax filers are barred from accessing three provisions—the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, and Premium Tax Credit. Immigrants therefore sometimes pay higher taxes than U.S. citizens in an otherwise comparable position.

- Sweeping tax legislation recently passed by the House of Representatives would apply new or stricter limits for immigrant tax filers to 10 additional areas of the tax code. In total, the number of provisions designed to exclude at least some immigrants would more than triple, from three provisions today to 11 under the bill that passed the House.

- The House bill would cause the tax code to consider immigration status in a more fundamental way than is the case today. While current law restricts immigrants’ eligibility for a handful of tax credits the House bill, by contrast, would take immigration status into account for the first time in determining eligibility for certain exemptions and deductions used to measure taxable income.

- While these restrictions are ostensibly aimed largely at undocumented immigrants, they would also affect immigrants with legal status and even U.S. citizens. The House bill’s changes to the Child Tax Credit, for example, exclusively affect families with children who are U.S. citizens or legal residents. Citizen spouses of immigrants would also lose access to some tax breaks, as would married citizen couples who file separate tax returns for reasons unrelated to immigration status.

- The House tax bill would transform the tax code from a somewhat neutral means of collecting revenue from people earning U.S. income regardless of immigration status, into a more obviously punitive structure that subjects immigrants to harsher treatment. This shift would come on the heels of a sharp break in IRS practice whereby the agency plans to begin handing over private taxpayer information to the Department of Homeland Security to assist in deportation actions. It would be unsurprising if some immigrants responded to this shift in policy by choosing not to pay the taxes they owe, rather than file under a punitive structure and have their personal information shared with immigration enforcement authorities as a result.

- This shift toward applying what are essentially different tax codes to different classes of individuals also raises concerns about the future direction of federal tax policy and whether it will begin to be used more frequently to punish politically disfavored groups.

Overview

The federal individual income tax applies to people receiving income in the U.S. regardless of their immigration status. Millions of immigrants with a variety of forms of legal status, and those with no legal status at all, pay income taxes every year through a combination of filing tax returns and having taxes automatically withheld from their paychecks.[1]

These tax payments are substantial. In previous research we estimated that the undocumented immigrant population, for example, paid $19.5 billion in federal individual income tax and $32.3 billion in various federal payroll taxes in 2022.[2] When combined with this population’s payment of various other taxes, including state and local taxes, their total annual tax contribution amounted to $96.7 billion. Immigrants with various forms of legal status pay billions of additional dollars in federal, state, and local tax not reflected in this figure.

For the most part, tax payments made by immigrants are made under the same set of rules that apply to U.S. citizens. The sections of the tax code that measure income, apply tax rates to that income, and offer various tax breaks that generally do not distinguish between citizens and non-citizens. Of the 155 tax breaks affecting individuals that have been identified by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation, for instance, just three consider immigration status in some way.[3]

Major tax legislation recently passed by the House of Representatives would represent a sharp break from current practice in at least two ways.

First, it would significantly increase the number of tax provisions for which immigration status is relevant to determining eligibility.

Second, it would broaden the types of provisions under which immigration status is taken into consideration. Specifically, immigration status would become relevant not just for claiming certain tax credits that reduce final tax liability, but also for the more fundamental calculation of various deductions and exemptions that go into measuring taxable income.

This brief outlines the ways in which immigration status is considered in the tax code today, and how that would change under the House bill.

Exclusions, Exemptions, and Deductions

The first step of the individual income tax calculation is to tally up the amount of income potentially subject to tax. From there, a variety of adjustments and exemptions are applied to arrive at an income amount that is subject to tax. Under current law, this foundational part of the individual income tax is applied in the same manner to both citizens and immigrant tax filers.

But the House bill would introduce four areas of departure where at least some immigrant filers would be granted a less favorable set of rules than citizens —typically by requiring that every member of the household possess a work-authorized Social Security Number (SSN) to claim the relevant exemption.[4]

- Senior citizen deduction. The House bill would create a new deduction of $4,000 for each filer aged 65 or older. The deduction is similar to the current bonus standard deduction received by senior citizens, though it would require claimants to hold work-authorized SSNs.

- Exclusion for student loans discharged at death. If a person facing student loan debt dies or becomes disabled and their loan is forgiven, the forgiven amount is considered income that is exempt from federal tax. This exemption is set to expire at the end of 2025 and the House bill would extend it, but only for people with work-authorized SSNs.

- Overtime pay exemption. Under current law, overtime pay is treated as any other form of salary or wage compensation and is subject to ordinary income tax rules. Under the House bill, some overtime pay would temporarily be carved out of the income tax base, but only for filers with work-authorized SSNs.

- Tipped income exemption. Similar to the exemption for overtime pay, tipped income is currently treated the same as any other form of earned income but the House bill would temporarily carve out a portion of this income for some taxpayers if they have work-authorized SSNs.

Tax Credits

Tax credits directly reduce the amount of tax liability owed by the taxpayer. Under current law only a small number of tax credits consider immigration status as an eligibility criterion. The House bill would significantly expand the ways in which eligibility for tax credits would be conditioned at least partly on immigration status.

- Child Tax Credit (CTC). Under current law, eligible children for purposes of the CTC only include those possessing work-authorized SSNs. This restriction was enacted in 2017 as a temporary measure accompanying a temporary increase in the CTC. The House bill would extend both the temporary CTC increase and the eligibility restriction and would tighten that restriction to apply to the parents of otherwise eligible children. A joint study by ITEP and other research organizations recently found that 4.5 million children who are either U.S. citizens or legal residents would lose access to the CTC under this proposal.[5]

- Premium Tax Credit (PTC). The PTC helps individuals and families purchase health insurance. Currently it is available both to citizens and immigrants who are lawfully present in the U.S. The House bill would significantly curtail the number of immigrants who qualify for this credit by denying access to those who have been granted asylum, temporary protected status, or various other legal statuses. Lawful permanent residents and people with certain other narrow forms of status would remain eligible.

- American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) and Lifetime Learning Credit (LLC).The AOTC and LLC are designed to defray some of the high cost of college. These credits can be of particular importance to immigrant students who do not qualify for federal student loans. The House bill would bar immigrants without work-authorized SSNs from claiming these credits.

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is designed to lift the after-tax pay of people working in low-wage jobs and to offset some of the payroll taxes they face on their earnings. It is one of just three provisions of current federal individual income tax law that consider immigration status, as the credit is only available to filers with a work-authorized SSN.[6] The House bill would leave this restriction intact.

Other Provisions

Two other provisions in the House bill would also apply less favorable tax treatment to immigrants than to U.S. citizens.

- Trump accounts. The House bill would create a new kind of tax-preferred savings account for children under age 8, called “Trump accounts.” Only U.S. citizen children who have at least one parent with a work-authorized SSN could access this type of account. The accounts would also be seeded with $1,000 for U.S. citizen children born between 2024 and 2028 if they have two parents able to provide work-authorized SSNs.

- Remittance tax.The House bill would subject transfers of funds to people in other countries to a 3.5 percent tax. U.S. citizens and nationals would not be subject to the tax as they could avoid it either by having their status as a citizen or national verified by the firm facilitating the transfer, or by receiving a refund of the tax paid via a refundable tax credit.

Impact on Married Couples and Mixed Status Families

Many immigrant taxpayers are members of mixed-status families, meaning that not all members of the household possess the same kind of citizenship or legal residence status. It is not uncommon, for example, for an immigrant with legal status to be married to an undocumented immigrant, and for that couple to have U.S. citizen children.

For the most part, the House bill takes the position that these mixed-status families should be barred from accessing the tax breaks described above. Under the House proposal, if even one spouse lacks a work-authorized SSN, then the entire family is ineligible for many of the tax reductions in question. For instance, if a U.S. citizen is married to an undocumented immigrant, or if a citizen child has an undocumented parent, then the House bill considers the citizen to have forfeited their right to a range of tax breaks.

To enforce this harsh approach on families with a mix of immigration statuses, the House bill takes the unusual step of denying many of the tax provisions described above to married couples who file separately. Without this restriction, a mixed-status family could continue to access at least some of the tax breaks described above by filing two separate returns and having the spouse who holds a work-authorized SSN use the provision.

This crackdown on the married filing separate status will impact not just mixed-status families but also married citizens who file separately for reasons entirely unrelated to immigration status. Married couples confronting substantial student loan debt, for example, often file separately as a way of gaining access to more affordable loan repayment options. Victims of identity theft may also choose to file separately if only one spouse’s identity has been stolen, as a way of mitigating some of the impact on the other spouse. In 2022, the IRS processed nearly 4 million returns that used the married filing separately status.

Discussion

The House bill would create a slew of new eligibility restrictions related to immigration that would make the code more punitive toward immigrants and complicate its administration for immigrants and citizens alike, at a time when IRS funding is being significantly reduced. State tax codes could also be made more complicated and punitive by the addition of these provisions to the federal code, as they frequently piggyback large portions of their own tax codes on federal law.

While the rationale for these proposals revolves mainly around making life more difficult for undocumented immigrants, despite their contributions to the economy and society, it is important to recognize that U.S. citizens and immigrants with legal status would also be impacted by these policy changes. Millions of U.S. citizen children, for instance, would be barred from accessing the Child Tax Credit as a result of the House bill.

It is important to keep in mind the context in which these changes are being proposed. The IRS recently agreed to begin sharing private taxpayer data with the Department of Homeland Security to assist in large scale deportations. This agreement has been widely reported in the press and is likely to lead at least some immigrants to forgo filing tax returns out of a legitimate concern that choosing to file could lead to their expulsion from the country. Choosing to reshape the tax code in the more punitive way envisioned in the House bill would only add to that disincentive to file.

In the short run, a drop in tax filing could lead to higher payments from immigrant workers who, like citizens, tend to overpay their taxes through withholding during the year. Deciding not to file would cause these individuals to forgo receiving refunds for their overpayments.

As time passes, however, the more likely result of applying a harsher tax code to immigrants and using their tax filings as a tool for immigration enforcement will be to encourage immigrants to find ways to forgo paying income taxes at all—such as by securing more informal employment, or self-employment, where withholding does not occur. Our research suggests that for every 10-percentage point drop in tax compliance among the undocumented population, tax revenues would decrease by $9.5 billion a year—with $8.6 billion of that coming from federal coffers and another $900 million from states and localities.[7]

The singling out of immigrant taxpayers for harsher treatment also raises a more foundational concern of whether this shift in policy could be the start of an effort to use the tax code to punish politically disfavored persons in general. If immigrants are classified as deserving of a harsher treatment based solely on their immigration status, it is not difficult to imagine future lawmakers making a similar argument for barring citizens convicted of crimes from accessing certain parts of the tax code. Over time, the definitions of who does, and does not, deserve to claim certain deductions and credits could grow even more complicated and politicized than they are today, with unpredictable and potentially damaging results.

Endnotes

[1] National Taxpayer Advocate. “Annual Report to Congress 2024.” January 2025.

[2] Davis, Carl, Marco Guzman, and Emma Sifre. “Tax Payments by Undocumented Immigrants.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. July 2024.

[3] ITEP analysis of: Joint Committee on Taxation. “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2024-2028.” Publication No. JCX-48-24. December 2024.

[4] The bill makes frequent reference to IRC Section 24(h)(7), which lays out the current requirement that the Child Tax Credit can only be claimed for children who possess a work-authorized SSN. Most of the provisions discussed in this brief would come to include an identical requirement.

[5] Lisiecki, Matthew, Danielle Wilson, Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Sophie Collyer, Megan Curran, Joe Hughes, Emma Sifre, and Christopher Wimer. “New Estimates of the Number of United States Citizen and Legal Permanent Resident Children Who May Lose Eligibility for the Child Tax Credit.” Joint paper by the Center for Migration Studies, Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, and Boston University Institute for Equity in Child Opportunity and Healthy Development. April 2025.

[6] Many state-level EITCs, by contrast, can be claimed by people without work-authorized SSNs. See: Butkus, Neva. “State Earned Income Tax Credits Support Families and Workers in 2024.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. September 2024.

[7] Whiten, Jon and Carl Davis. “Turning IRS Agents to Deportation Will Reduce Public Revenues.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. February 2025.