Today’s pandemic-driven recession continues to lay bare our nation’s economic and racial disparities. Low-wage workers, disproportionately women and Black and brown people, have lost their jobs at a far higher rate than their wealthier neighbors, resulting in cascading hardships that are directly affecting our nation’s children.

More than one in six families with children experienced food insecurity over the past week (according to the latest data) and nearly a third of adult renters with children have not been able to keep up with the cost of housing. Children struggling with hunger and the compounding stress of these events are at greater risk for poor health (in the short- and long-term), developmental delays and poor academic performance.

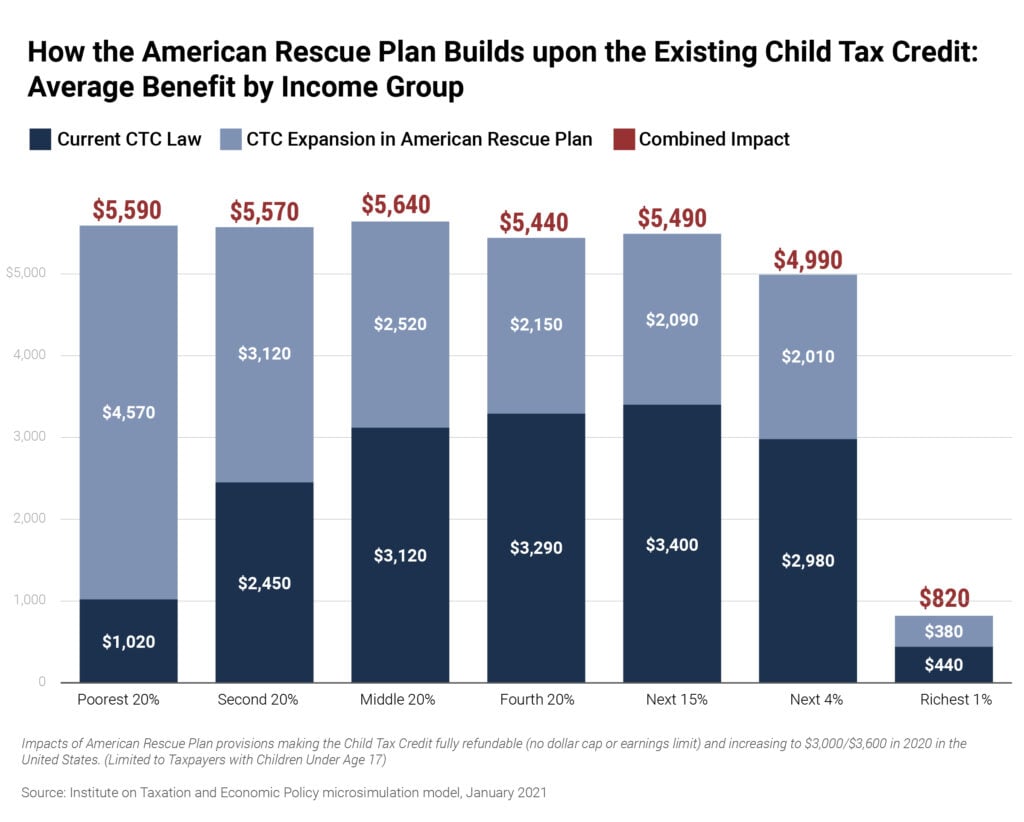

Bold federal and state action can mitigate these hardships and put families on a more economically sound footing. Fortunately, President Joe Biden’s coronavirus relief package, the American Rescue Plan, offers to provide a significant temporary expansion of the federal Child Tax Credit (CTC). The proposal would double the size of the existing CTC, increase the maximum credit and make the credit fully refundable. In a recent report, ITEP analyzed the potential impact of that expansion and found that while the plan would provide a financial boost to most of the nation’s families with children, it would be most beneficial for low-income families and would address structural inequities that currently exclude a larger share of Black and Hispanic children from the credit.

If Congress does act and enact President Biden’s CTC expansion, states could simply couple to that federal change. The changes, while temporary, could become the foundation of a permanent state-level credit over the long-term.

But state lawmakers need not wait for legislative action in DC. They can take immediate steps to ensure that their state’s most vulnerable children are positioned to succeed.

Child Tax Credit Enhancements Under the American Rescue Plan Are Promising, But States Do Not Need to Wait for Federal Action

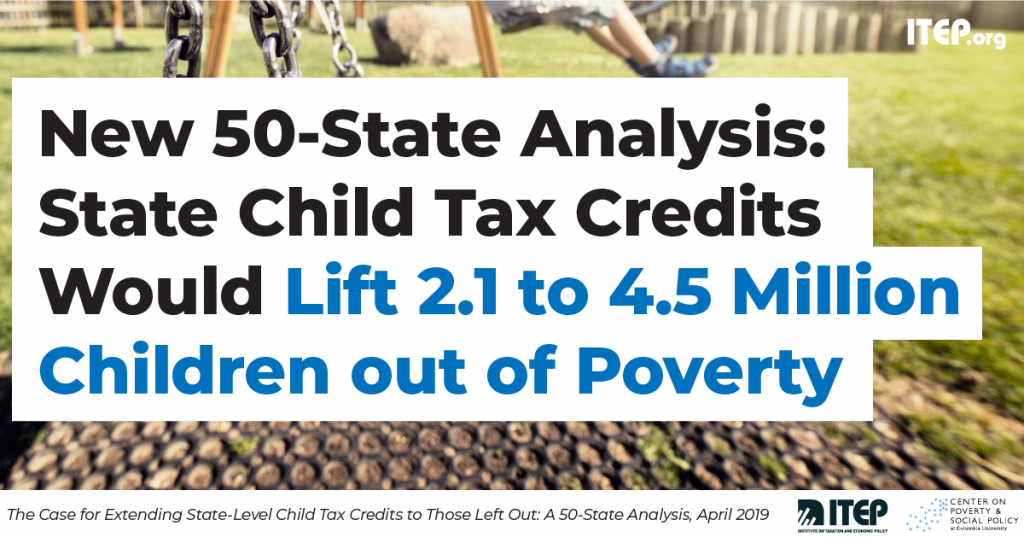

State-level CTCs are a powerful tool that states can employ to remedy inequities created by the current structure of the federal CTC while significantly reducing child poverty and deep poverty in all states.

In the absence of immediate federal action, states have several options:

- Lawmakers can create stand-alone refundable CTCs that would ensure that all children, regardless of their family’s employment or immigration status, could benefit. The existing federal CTC leaves behind nearly 40 percent of children who live in families too poor to qualify for the full credit. The CTC, as currently designed, also restricts eligibility to children with Social Security Numbers and therefore leaves out non-citizen children—most of whom are children of undocumented immigrant workers (often ITIN filers) who have already been denied thousands in federal stimulus dollars under the Trump Administration.

The advantage of implementing a credit separate from the federal CTC is that states can avoid the existing shortfalls of the federal credit (in particular, the earnings requirement and lack of full refundability) that preclude many lower-income families from receiving the full benefit. Instead, states should make full use of the flexibility they have to determine the scope and scale of their own state-level credits without these onerous restrictions. It is essential that stand-alone credits are refundable and available to all low-income children regardless of their families’ earnings or immigration status.

This flexibility includes setting state-specific phaseout ranges that will help determine how precisely targeted the credit will be toward the lowest-income children. The existing federal CTC does not begin to phase out until income reaches $400,000 a year for married parents or guardians (or $200,000 for single parents and guardians). Setting a lower phase-out range could target the credit more effectively to families in need while dramatically lowering the potential cost of such a credit.

Under this scenario, states also have the flexibility to provide a more robust credit to younger children in their formative years when such an income boost may be most consequential. Additionally, this step allows lawmakers to address inequities within their state tax codes which, in most states, take a much greater share of income from low- and middle-income families than from wealthy families.

- Lawmakers can enact a CTC as a simple percentage of the federal credit, in combination with a minimum credit. Like the approach most states take with their Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC), states can also piggyback CTCs on top of federal rules at a flat percentage rate. For example, a state credit calculated as 10 percent of the federal CTC would amount to a $200 state CTC for any child who receives the full credit. Under this approach, however, state lawmakers should take care not to copy the worst features of federal law. That is, they should ensure that children in families too poor to receive the full benefit of the federal credit are not denied full state benefit as well. In this example, all low-income families would receive the full $200 per-child state benefit.

This option would still rely upon the federal CTC’s high phaseout range (starting at $400,000 for married parents and guardians, $200,00 for single parents and guardians)—providing more sweeping tax cuts to families throughout the income distribution at a relatively high cost to state coffers. But states could easily act to implement their own phase-out range.

One advantage to this approach is that if Congress makes the federal proposal permanent, the state version would essentially remain the same (tied to a specific date), but without the need for the minimum credit.

- Lawmakers can fill the gap for the children left behind by the federal CTC. For tax filers and their families among the bottom 20 percent of earners, virtually no child receives the full credit. More than a third of all white children, more than 45 percent of Hispanic children, and nearly half of Black children are in families too poor to receive the current full federal CTC. State lawmakers can make up for this shortcoming by ensuring that those children are brought up to the full $2,000 credit, or a percentage of that credit determined by the state. This approach ensures that a state’s lowest-income children are not left behind.

Unless otherwise specified, the approaches under options two and three would fail to bring in non-citizen children. Many of these children’s parents are undocumented immigrants, or filers using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs). Children who lack Social Security Numbers became ineligible for the federal CTC credit under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). These families have been especially hard hit during the recession and have cruelly been denied federal coronavirus relief.

The Time is Now

Boosting family income can expand opportunities for children and drastically reduce child poverty. Lifting low-income families’ incomes when a child is young is associated with improved immediate well-being, better health outcomes, more schooling and improved school performance, more hours worked and higher earnings in adulthood. State lawmakers can take immediate steps to improve the lives of their youngest and most vulnerable constituents.

A number of states, including Connecticut and Maryland, have introduced bills to provide state-level CTCs this session. Some other states have proposed or enacted one-time, temporary rebates for families with children. While one-time rebates can boost the incomes of those most in need, a permanent, refundable solution is preferable in addressing our nation’s long-term economic and racial inequities.

What are we waiting for? The time to act is now.