Read this policy brief in PDF form

Over the past several decades, state corporate income taxes have declined markedly. One of the factors contributing to this decline has been aggressive tax avoidance on the part of large, multi-state corporations, costing states billions of dollars. The most effective approach to combating corporate tax avoidance is combined reporting, a method of taxation currently employed in more than half of the states that tax corporate income. The two most recent states to enact combined reporting are Rhode Island in 2014 and Connecticut in 2015.

In several states, including Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont, lawmakers adopted the policy after first carrying out in-depth studies of its potential effects. This policy brief explains how combined reporting works.

How Combined Reporting Works

For corporations that only do business in one state, paying corporate income taxes can be simple – all of their profits are taxable in the state in which they are located. For corporations with subsidiaries in multiple states, the task of determining the amount of profits subject to taxation is more complicated. There are broadly two ways of doing this: combined reporting, which requires a multi-state corporation to add together profits of all of its subsidiaries, regardless of their location, into one report, and separate accounting, which allows companies to report the profit of each of its subsidiaries independently.

For example, if the Acme Corporation has three subsidiaries in three states, a combined reporting state would require Acme to report the profits of the four parts of the corporation as one total, on the grounds that each of the parts of the corporation contribute to its profitability. In contrast, a separate accounting state would require only those parts of the Acme Corporation that have “nexus” in that state – that is, enough in-state economic activity to be subject to the state’s corporate income tax – to report their profits, even if the out-of-state parts of the corporation are responsible for the bulk of Acme’s overall profits.

As of 2017, twenty-five states and the District of Columbia (DC) have adopted combined reporting. The two most recent states to do so were Rhode Island in 2014 and Connecticut in 2015.

As of 2017, twenty-five states and the District of Columbia (DC) have adopted combined reporting. The two most recent states to do so were Rhode Island in 2014 and Connecticut in 2015.

What Businesses Are Affected by Combined Reporting?

Combined reporting only affects a small sliver of all companies. Most businesses, and the vast majority of smaller businesses, are “pass-through” entities that already effectively face a form of combined reporting because they are not composed of multiple subsidiaries and all their profits are combined on the tax returns of their individual owners. Only “C-corporations,” which are just 4.7 percent of U.S. businessesi and tend to be larger corporations, can even potentially be affected by combined reporting, as these are the only businesses that pay taxes on their profits at the entity level and have the option to subdivide their business into multiple subsidiaries in multiple states. Out of that 4.7 percent, only those that operate in multiple states, turn a profit, and are currently benefitting from separate accounting might face higher taxes as a result of combined reporting.

To get a full picture of combined reporting’s effects, the state of Rhode Island required corporations to calculate their taxes using both combined reporting and separate accounting for two years, 2011 and 2012. The state found that only 28 percent of companies doing business in Rhode Island were C-Corporations, and only 29 percent of those C-Corporations would pay higher taxes under combined reporting, meaning only about 8 percent of Rhode Island businesses would see tax increases.ii Yet this small minority of Rhode Island businesses was responsible for $22 to $23 million of tax avoidance in 2012.

Separate Accounting Enables Tax Avoidance

In addition to allowing companies to structure their operations so that some subsidiaries avoid taxation, separate accounting enables corporations to use gimmicks to shift their profits from state to state to avoid taxation. The most infamous example of this is the passive investment company (PIC) loophole.

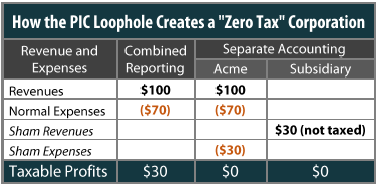

Here’s how the PIC loophole works: suppose the Acme Corporation is based in State A, which uses separate accounting. If Acme has sales of $100 million and expenses of $70 million, its taxable profits ought to be $30 million. If Acme sets up a subsidiary – commonly referred to as a passive investment company (PIC) – in a state like Delaware that does not tax intangible property (such as trademarks and patents) and makes that subsidiary the owner of Acme’s intangible property, then the subsidiary can charge Acme for the use of these trademarks. Although Acme’s payment to the PIC is a transfer of funds within the company, under separate accounting this expense counts as a cost of doing business and can therefore be subtracted from Acme’s income in determining its taxable profits in State A. Since the subsidiary can charge Acme whatever it wants for the use of the trademarks, Acme may actually be able to zero out its taxable profit through this sham “expense.”

In the example below, Acme’s subsidiary (i.e. its PIC) charges it $30 million for the use of the trademarks, which reduces Acme’s taxable profit in State A to zero. Because the subsidiary exists only to lease trademarks to Acme, none of the subsidiary’s sham “income” is taxable in Delaware. Furthermore, because the PIC does not have nexus in State A, Acme pays no tax to State A on the profits generated by the PIC. A wide variety of major corporations currently use the PIC loophole in separate accounting states, including Home Depot, Ikea, and Toys R Us.

Unfortunately, the PIC loophole is just one of many tax avoidance techniques available to corporations operating in separate accounting states. Examples include “captive real estate investment trusts (REITs),” asset-transfer shelters, and transfer-pricing shelters.

Combined Reporting: A Simple Approach to Preventing Tax Avoidance

In a combined reporting system, all income and expenses of Acme and its subsidiaries would be added together, so that PICs and other loopholes would have no impact on the company’s taxable profits. For example, if Acme tried to use the PIC loophole, the subsidiary’s $30 million of income from the sham transaction would be canceled out by Acme’s $30 million of expenses, with a net impact of zero on Acme’s taxable profits.

Of course, combined reporting is not the only option available to states seeking to prevent the use of accounting gimmicks such as the PIC loophole. States can also close these loopholes one at a time. For example, several states have enacted legislation that specifically prohibits shifting income to tax haven states through the use of passive investment corporations. The main shortcoming of this approach is that in the absence of combined reporting, multi-state corporations will always be able to develop new methods of transferring profits from high-tax to low-tax states. The only limit to the emergence of new approaches to transferring income to tax haven states is the creativity of corporate accountants. Combined reporting is a single, comprehensive solution that eliminates all potential tax advantages that can be derived from moving corporate income between states.

Worldwide Combined Reporting: Staying Ahead of the Curve

Even most states that require combined reporting could improve it further by adopting “worldwide” combined reporting. Most states limit the requirement to the “water’s edge” of U.S. borders or allow corporations to choose whether to report on a worldwide or water’s edge basis. Just as separate accounting allows corporations to avoid taxes by shifting income between states, the water’s edge rule leaves open the possibility for companies to do so by shifting income to other countries. Worldwide combined reporting staves off this tax avoidance strategy. A second-best option is for states that currently allow a choice between worldwide and water’s edge treatment to follow Montana’s lead and require those choosing water’s edge treatment to also report their subsidiaries located in known international tax havens.

Combined Reporting Levels the Playing Field

Combined reporting is fairer than separate accounting because it ensures that a company’s tax should not change because its organizational structure changes. It creates a level playing field between smaller and larger companies: small companies doing business in only one state can’t use separate accounting to reduce their tax because they have no business units in other states to shift their income to. Large, multi-state corporations will find it easier to avoid paying taxes using separate accounting because they have business units in multiple states.

Conclusion

Strategies that broaden the corporate income tax base by eliminating loopholes can ensure that profitable corporations pay their fair share for the public services they use every day, can level the playing field between multistate corporations and locally based companies that cannot avail themselves of tax avoidance schemes, and can help balance state budgets without requiring unpopular increases in tax rates. Requiring combined reporting is the single best strategy available to lawmakers seeking to stamp out accounting shenanigans by large and profitable corporations.[i][ii]

[i] United States Joint Committee on Taxation, Choice of Business Entity: Present Law and Data Relating to C Corporations, Partnerships, And S Corporations, April, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4765 .

[ii] Rhode Island Division of Taxation, Tax Administrator’s Study of Combined Reporting, March 15, 2014, http://www.tax.ri.gov/Tax%20Website/TAX/reports/Rhode%20Island%20Division%20of%20Taxation%20–%20Study%20on%20Combined%20Reporting%20–%2003-17-14%20FINAL.pdf .