Most Americans have likely forgotten about the wave of news stories a few years back detailing how some massive American companies planned to recharacterize themselves as foreign entities for tax purposes using corporate “inversions.” Just as you might occasionally wonder “what ever happened to” a child star who has lately been absent from the spotlight, you might wonder whether the corporate inversion issue was ever resolved. The answer: It wasn’t, and several lawmakers recently introduced legislation to block the practice.

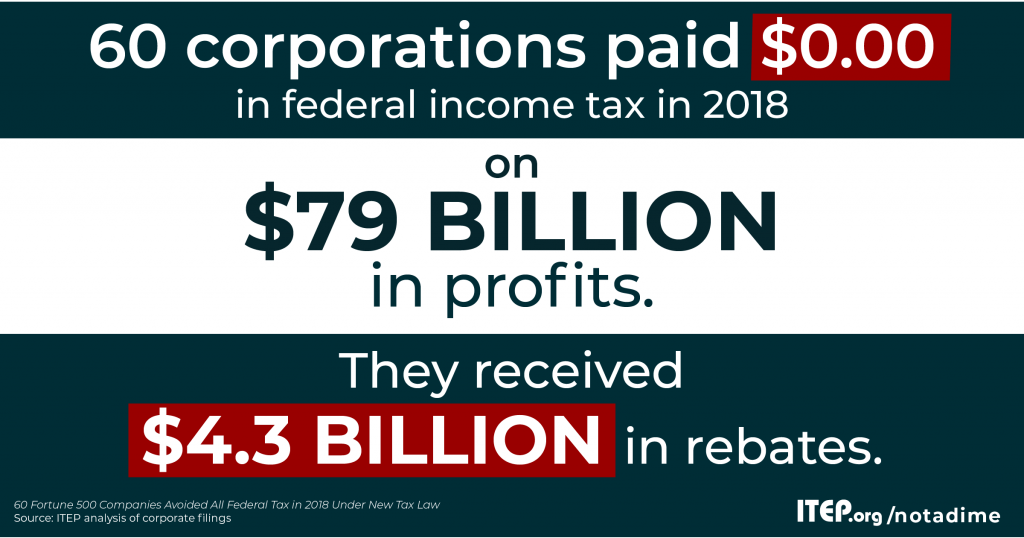

The public has not heard much about corporate inversions since the 2017 enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TJCA). There have been few major inversions partly because Congress provided, in TCJA, different ways for corporations to avoid paying taxes. In fact, at least 60 profitable Fortune 500 corporations paid no federal income taxes in their first year under the new law. TCJA also created new ways for American multinational corporations to avoid taxes on profits that they claim to generate offshore. This may have slowed down inversions, but it is not a victory for Americans who pay for the infrastructure and other public investments that corporations use to generate their profits.

If a future Congress and president enact a real tax reform, one that requires corporations to pay their fair share and ends TCJA’s various corporate breaks for offshore profits, then companies will use inversions and other tactics to dodge taxes once again—if lawmakers let them. That’s why any real tax reform will include something like the Stop Corporate Inversions Act, introduced last week by Sens. Dick Durbin and Jack Reed to block inversions.

Congress Never Provided More than a Weak Obstacle to Inversions

A corporate inversion involves an American corporation arranging to be acquired by a foreign one so that it can claim it is no longer an American company for tax purposes. A few companies tried this in the 1980s, sometimes creating an offshore shell company that was wholly owned by the shareholders of the American company, then declaring that the offshore shell company acquired the U.S. company so that the resulting entity was technically “foreign” even though no operations or jobs moved abroad.

This was a ridiculous fiction, and Congress enacted a law in 2004 that stopped inversions that were most obviously accounting and legal gimmicks.

But that law failed to block some of the slightly less brazen attempts to use inversions as a tax dodge. Under the 2004 law, if the merger of an American company and a foreign one resulted in an entity that was more than 80 percent owned by the same shareholders who owned the American company, then the resulting entity would be taxed as a U.S. corporation.

As a result, some American corporations arranged mergers with foreign companies—real ones, not shell companies—and ensured that their shareholders would maintain control (more than 50 percent ownership) but less than 80 percent ownership. Again, operations and jobs did not usually leave the United States.

Because the merger was with a real foreign company, the whole deal contained a tiny bit of reality. But American companies were still just using paperwork and accounting gimmicks to tell the IRS that they were now “foreign” corporations for tax purposes.

For years, a handful of companies would invert annually, and in some years none would invert. But the practice picked up pace in 2014 when 10 companies, with combined assets of $300 billion, announced that they were considering or planning inversions. The biggest and most attention-grabbing was the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer. The practice seemed to threaten to unravel the entire corporate income tax.

Attempts to Finally Block Inversions

In response, congressional Democrats introduced the first version of the Stop Corporate Inversions Act, which provides the obvious solution. Under this legislation, the entity resulting from the merger of an American company and a foreign one would be taxed as a U.S corporation if the American partner to the merger maintains a controlling interest, meaning its shareholders own more than half of the resulting entity. The legislation would also treat the resulting entity as an American company if it is managed and controlled in the United States. It provides exceptions if the company is doing substantial business in the foreign country.

Congressional Republicans refused to enact this legislation because, they argued, the only answer was to cut the federal corporate tax so much that American corporations would no longer have any desire to try to avoid it.

The Obama administration responded to the impasse by issuing regulations ensuring that, at very least, existing law was enforced adequately. The regulations were somewhat successful in clarifying that certain techniques to avoid the law would not work, including American corporations buying other American companies just before their merger with a foreign company to tilt the U.S.-foreign ratio in their favor, and attempts by foreign-owned American companies (which technically includes inverted companies) to access offshore cash by manipulating debt. These regulations caused Pfizer to back away from its second attempt at an inversion.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

When lawmakers enacted TCJA at the end of 2017, congressional Republicans got their wish. The law slashed the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, and it changed rules for offshore profits to allow different types of breaks than existed under the old system.

Multinational corporations are still figuring out how to navigate the new law, and it may be a while before it is clear whether they have any incentive to use inversions to further drive down their taxes.

But TCJA is itself unsustainable. It is siphoning off $1.9 trillion of revenue over a decade and the majority of Americans believe it should never have been enacted. When a future Congress enacts a real tax reform that requires corporations to pay for the benefits of operating in this country, some companies will doubtless seek out inversions and other tactics to avoid that responsibility.

And that is why we still need the legislation proposed since 2014 by Congressional Democrats, the Stop Corporate Inversions Act, the same legislation reintroduced last week by Sens. Durbin and Reed.