Read Report as PDF (Includes Appendix)

Introduction

One of the most important functions of government is to maintain a high-quality public education system. In many states, however, this objective is being undermined by tax policies that redirect public dollars for K-12 education toward private schools. Seventeen states currently divert a total of over $1 billion per year toward private schools via tax credits. Nine of these states’ credits are so lucrative that they offer some upper-income taxpayers a risk-free profit on contributions they make to fund private school scholarships.1 Now, federal legislation has been introduced that would further the  ability of wealthy individuals to undermine the public education system and profit off their donations to nonprofits serving private schools. Unlike most state laws, the federal legislation does not even cap the amount of funds that could be redirected from the Treasury into unaccountable, nonprofit organizations supplementing tuition at private schools. The loss of federal and state revenue directed at public schools would weaken the ability of public schools to serve increasing numbers of students in poverty as well as students with disabilities and English-language learners. We suggest that rather than expand these voucher tax shelters at the federal level, Congressional efforts to reform the tax code should be used as an opportunity to eliminate current loopholes that encourage participation in these voucher schemes.

ability of wealthy individuals to undermine the public education system and profit off their donations to nonprofits serving private schools. Unlike most state laws, the federal legislation does not even cap the amount of funds that could be redirected from the Treasury into unaccountable, nonprofit organizations supplementing tuition at private schools. The loss of federal and state revenue directed at public schools would weaken the ability of public schools to serve increasing numbers of students in poverty as well as students with disabilities and English-language learners. We suggest that rather than expand these voucher tax shelters at the federal level, Congressional efforts to reform the tax code should be used as an opportunity to eliminate current loopholes that encourage participation in these voucher schemes.

Public Loss Private Gain: How School Voucher Tax Shelters Undermine Public Education examines current trends in state tuition tax credit (TTC) policies and how proposed federal TTC policy could harm school district finances across the country. The report is divided into five sections. Part I explains the concept of tuition tax credits, why they were created, how they operate, and why they prove to be more lucrative for wealthy taxpayers than other charitable giving incentives. Part II describes the variations in how TTCs are set-up and supervised by states. Part III focuses on the proposed federal legislation, the Educational Opportunities Act, and its various shortcomings, including how it would create avenues for corporations and successful investors to profit off their donations. Part IV outlines other issues associated with TTCs, including how they undermine public education. Part V concludes with action steps at the state and federal level that could protect education funding and reduce the prevalence of these schemes.

Part 1: The Origins and Design of Tuition Tax Credit Voucher Schemes

Currently, seventeen states have policies that generate private school vouchers through a tax credit mechanism. These policies, known as tuition tax credits (TTCs), were created by conservative think tanks as a way to direct public funds to private (often religious) schools even when traditional voucher programs are unpopular with the public or outright unconstitutional.2At least eighteen states3 are constitutionally forbidden from offering direct vouchers for religious schools, though the courts in most of those states have tended to look the other way when those vouchers are disguised as tax credits.

Tuition tax credits operate as follows: taxes owed to a state by individuals or corporations can be diverted into charitable donations to nonprofit entities that then bundle the donations and distribute tuition checks to families to use to attend private schools. The entities that package the donations and distribute the funds to parents are known as Scholarship Granting Organizations (SGOs) or voucher nonprofits. These entities are registered nonprofits with very little state oversight that can direct dollars toward specific types of schools (for example, schools affiliated with a particular religion or schools promoting a specific curricular approach). The lack of accountability and oversight of voucher nonprofits are detailed in Part III.

Many voucher advocates see TTCs as a way for wealthy taxpayers to help low-income taxpayers and their children “trapped in failing public schools”4 to attend a presumably better non-public school. The student’s private school tuition is subsidized, at least initially, by affluent individuals and sometimes corporations. While some individuals and corporations may believe that donations to support private school education will result in better outcomes for students, one should not be misled by the purported generosity of those who donate to voucher nonprofits. Donors in many states with TTCs see the entire cost of their “donation” reimbursed with tax cuts, and in some cases donors are even profiting from their donations to voucher organizations by claiming multiple tax cuts on each donation. Both situations bear little resemblance to philanthropy, and instead undermine the tax base that funds public education.

and their children “trapped in failing public schools”4 to attend a presumably better non-public school. The student’s private school tuition is subsidized, at least initially, by affluent individuals and sometimes corporations. While some individuals and corporations may believe that donations to support private school education will result in better outcomes for students, one should not be misled by the purported generosity of those who donate to voucher nonprofits. Donors in many states with TTCs see the entire cost of their “donation” reimbursed with tax cuts, and in some cases donors are even profiting from their donations to voucher organizations by claiming multiple tax cuts on each donation. Both situations bear little resemblance to philanthropy, and instead undermine the tax base that funds public education.

Here’s How it Works

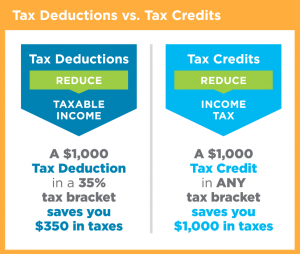

For most types of charitable donations, taxpayers receive a tax deduction that acts an incentive at the margin to donate. In a state with a 6% income tax rate, for example, donating $1,000 to charity means that $1,000 will no longer be subject to tax, resulting in a tax cut of $60 for the taxpayer (or 6% of the amount donated). Under a tuition tax credit, rather than a deduction, a state gives the donor a tax benefit far beyond what would be available for other charitable donations. TTCs offer tax cuts ranging from 50% of the contribution amount (Indiana and Oklahoma) to 100% of the total contribution (Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Montana, Nevada, and South Carolina). Credits equal to 100% of the contribution are designed to allow taxpayers to redirect their tax payments toward private institutions at no cost to themselves. In practice, the actual tax benefits for credit recipients can sometimes even exceed the size of the donation. When the impact of state tax credits is combined with federal tax deductions (and sometimes state tax deductions as well), some taxpayers in nine states can actually turn a profit by making these so-called “donations” to voucher nonprofits. Those states are Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Montana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.1

How Long Has This Been Going On?

Tuition tax credit programs began in 1997, but since at least 2011, the IRS has essentially sanctioned allowing taxpayers to claim a federal charitable deduction for private school scholarship donations even when those donations are also subsidized with a state tax credit.5

| HERE ARE A FEW EXAMPLES OF HOW THESE PROFIT-GENERATING VOUCHER TAX SHELTERS ARE PROMOTED ACROSS THE COUNTRY. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As a result, wealth-management organizations, voucher nonprofits and individual schools promote “double-dipping” (receiving a tax benefit on the same donation at both the federal and state level) as a profitable scheme for donors. After the release of the IRS memo, scholarship granting organizations in over a dozen states have been advising their donors that their contributions are eligible for a federal tax deduction in addition to a state tax credit.13 For some high-income taxpayers, this dual benefit can turn a scholarship “donation” into a voucher tax shelter where the total tax cut received significantly exceeds the size of the original donation.

The examples on page three demonstrate that benefiting from a voucher tax shelter is a major reason to participate in a TTC. It should therefore come as little surprise that in some states, the entire allotment of available credits is often claimed just hours after state tax officials begin accepting applications. In Georgia, the state’s entire allotment of $58 million in tuition tax credits was claimed in a single day on January 3, 2017.14 A few months earlier, the same occurred within a matter of hours with regard to $67 million of credits in Arizona and $763,550 in credits in Rhode Island.15 While taxpayer confidentiality laws generally conceal the magnitude of the benefits received by specific claimants, a journalist in South Carolina estimated that one savvy, anonymous taxpayer was able to reap a profit of between $100,000 and $638,000 in 2014 by stacking state, and possibly federal, deductions on top of tuition tax credits.16

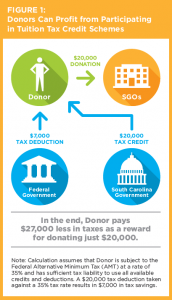

A close look at South Carolina’s tuition tax credit illustrates how this voucher tax shelter works. In the Palmetto State, taxpayers receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for any “donations” they make to certain nonprofit scholarship funding organizations–thereby making the donation essentially costless to the taxpayer. Assuming the taxpayer itemizes on their federal return, the immediate federal tax consequence of a donation is twofold: the taxpayer’s charitable deductions increase by the amount of the donation, and the taxpayer’s state income tax deduction falls by the amount of the tax credit they received. At first, this may appear to result in a wash for the taxpayer. But this is not always the case because in some instances, charitable deductions are more valuable than deductions for state income taxes paid.

At the federal level, one of these instances arises when taxpayers are subject to the individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).17 The AMT is designed to ensure that taxpayers receiving generous tax breaks pay at least some minimum level of federal income tax. This is accomplished by denying certain tax breaks under AMT rules, including the deduction for state and local tax payments. Charitable donations, however, are still tax deductible under the AMT. So the ability to reclassify state income tax payments as charitable donations via a TTC can be of significant benefit to taxpayers subject to the federal AMT–a group overwhelmingly comprised of taxpayers earning over $200,000 per year.18 When combined with a dollar-for-dollar state tax credit, this means that a private school “donation” in South Carolina is better than costless, and can actually result in a risk-free return as high as 35% of every dollar “donated.” Figure 1 illustrates how this scheme would operate for a donor contributing $20,000 to a voucher nonprofit.

Regardless of the purported educational merits of state tuition tax credit programs, it is undeniable that the voucher tax shelters created by these credits have contributed to their reach. The potential for wealthy individuals to turn a profit by claiming these credits is accelerating the diversion of critical resources away from public schools.

Part 2: State Policy Overview

Tuition tax credits for private education are intended to encourage businesses and/or individuals to contribute to organizations that distribute private school scholarships to qualifying students, but there is considerable variation in how they achieve this goal. Of the seventeen states that offer a tuition tax credit, seven states only extend their credits to businesses (Florida, Kansas, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Dakota). The other ten states allow both businesses and individuals to claim tuition tax credits, though four of those states (Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, and Virginia) allow businesses to claim a larger credit than individual taxpayers. Sixteen states offer nonrefundable tuition tax credits, with some of these limited to a certain percentage of tax liability (Louisiana is the lone exception where credits can exceed tax liability). Limits on the total amount of funds allowed to be redirected from state coffers toward tuition tax credit donations vary widely. Oklahoma’s TTC program is capped at just $3.4 million, for example, while Florida’s cap is set at almost $700 million for Fiscal Year 2018.19

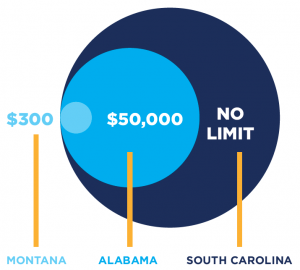

There are also disparities in the amount of money that can be donated by individuals to voucher nonprofits in exchange for tax credits. Montana’s credit is modest compared to other states, capping the individual contribution eligible for tax credits at $150, or $300 for couples filing jointly.20 In contrast, Louisiana and South Carolina allow individuals and businesses to receive tax credits for donations of any size, though South Carolina caps overall credits at $10 million per year.21

There are also differences in the kinds of students who are eligible for the private school voucher. Four states allow any student, regardless of family wealth, to be eligible for a voucher. This often means that students receiving the vouchers were already attending private school and the state is now subsidizing their education when it was not previously paid for by the state. Eight other states allow families who are not typically considered low-income (for example, families of four making up to $48,500) to be eligible for vouchers.22

There is also wide variation in the requirements for schools  that accept students with vouchers paid for by TTCs. Nine states do not require voucher recipients to take any test to measure their academic progress against their peers in the public school system while three states require that voucher students take a national test to measure student achievement.23 As detailed in Part III, the lack of information on how students are performing academically is highly problematic for programs that receive millions of taxpayer dollars.

that accept students with vouchers paid for by TTCs. Nine states do not require voucher recipients to take any test to measure their academic progress against their peers in the public school system while three states require that voucher students take a national test to measure student achievement.23 As detailed in Part III, the lack of information on how students are performing academically is highly problematic for programs that receive millions of taxpayer dollars.

Part 3: The Educational Opportunities Act

Tax Policy Implications

For the past three Congresses, Sen. Marco Rubio (FL) and Rep. Todd Rokita (IN) have introduced legislation that would create a federal tuition tax credit program called the Educational Opportunities Act (HR. 895/S.148). Both legislators hail from states with broad tuition tax credit programs and would like to see a replication of these programs at the federal level with the goal of having their legislation incorporated into a broader tax reform bill if it cannot pass by itself.26

The Educational Opportunities Act (EOA) provides a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for individuals and corporations that donate to voucher nonprofits (referred to as “scholarship granting organizations†or SGOs) that provide vouchers for low-income students to attend private schools. Low-income students are defined in the statute as families making less than 250% of the poverty line (or less than $60,750 per year for a family of four). Individuals and married couples donating to SGOs would be limited to $4,500 in federal credits per year while corporations could receive credits of up to $100,000 per year.27 Because this is a federal bill, it is not necessary for a taxpayer to live in a state with a TTC program to benefit from this legislation.

By granting a dollar-for-dollar credit, the EOA privileges voucher nonprofits over virtually every type of charity or nonprofit including homeless shelters, veterans’ support organizations, nonprofits serving victims of domestic violence, etc. When taxpayers donate to most tax-exempt charities they receive a federal tax deduction that could be worth between 10 and 40 cents on each dollar donated. This is a generous tax incentive designed to encourage charitable giving. In contrast, the EOA posits that SGOs are deserving of a far more lucrative benefit: a 100% tax credit on each dollar donated (up to the maximum eligible amounts identified above). If a taxpayer donates one dollar to a SGO, they do not just receive 10-40 cents back, but rather they receive a full dollar back. In effect, this bill provides SGOs with a tax advantage that is many times more generous than what is afforded to other charities. Under certain circumstances, the EOA goes even further by allowing taxpayers to turn a profit for playing a role in transferring public funds to SGOs. This voucher tax shelter can happen in one of two ways.

First, while the EOA prohibits a donor from receiving a federal deduction and a federal credit on the same donation, it appears to allow donors in states with TTC programs to double-dip in a different way: claiming a state tax credit and this new federal tax credit for the same donation. As explained in Part I, state tax credits range as high as 100% of the amount donated. This means that some taxpayers could double their money, claiming a dollar in state credit and a dollar in federal credit for each dollar donated. The result would be a risk-free, 100% profit of up to $4,500 per year for individual taxpayers, or up to $100,000 per year for corporations.

The second tax shelter available under the EOA is limited to corporations and successful investors. Taxpayers who opt to donate stock, rather than cash, to SGOs would receive a federal tax credit equal to the fair market value of the stock they donated (again, up to $4,500 for couples or $100,000 for corporations). In effect, this credit allows investors to receive the same benefits as if they had sold their stock, without having to actually do so. As a result, investors can avoid paying any tax on the capital gain portion of that stock’s value, effectively making this “donation” more lucrative than if the investors had simply sold the stock and kept the money for themselves.

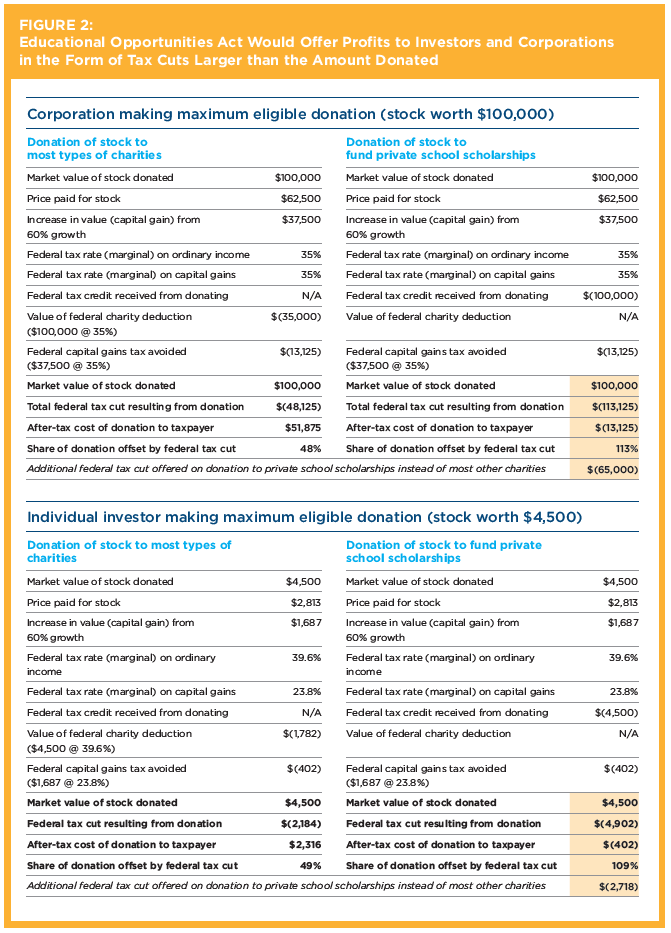

Figure 2 in the appendix to this report details the workings of this scheme in more detail for a corporation donating stock worth $100,000, and for a couple donating stock worth $4,500. In both cases, if the taxpayer originally acquired this stock for less than its current value, this “charitable donation” would effectively turn a profit because the tax cuts received would be larger than the actual value of the donation.

In the case of the corporation donating stock worth 60% more than its original purchase price, the result would be $113,125 in federal tax cuts in exchange for a donation worth just $100,000–a tidy $13,125 profit for agreeing to participate in this transfer of funding to private schools. And the actual voucher tax shelter could be even larger than this amount in most states because state-level capital gains taxes could also be avoided using this technique.

Figure 2 also illustrates how voucher nonprofits would be afforded an advantage over every other type of charitable nonprofit. A corporation in this situation would be granted $65,000 more in tax cuts if it chooses to donate to fund private school scholarships rather than most other types of charitable causes.

The math is very similar for an individual taxpayer donating stock worth $4,500, though the scale of the profits involved is obviously much smaller. In the example in Figure 2, a $4,500 donation triggers a tax cut worth $4,902–resulting in a profit to the taxpayer of $402. While a benefit of this size may not be incredibly consequential to the most successful investors, it is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which exploiting this scheme would become a routine aspect of tax planning for taxpayers with recurring capital gains income. Also of note is the fact that this person could receive a far steeper reduction in tax from donating to private school scholarships ($4,902) than donating to nearly any other charity ($2,184)–a difference of $2,718 per year.

Education Policy Implications

The goal of the EOA is to create a nationwide system for publicly funding private schools. The EOA would allow a taxpayer to receive a federal tax credit in return for donating to voucher nonprofits in any state, including nonprofits located in states where the taxpayer does not reside. Notably, however, voucher proponents expect that new voucher nonprofits would spread nationwide in a short amount of time if the EOA were enacted. For example, one of the largest voucher nonprofits in the country is the Children’s Scholarship Fund with partners in 17 states. At a recent event in Washington, D.C., Darla Romfo, the President and CEO of the Children’s Scholarship Fund, indicated that if a federal tax credit were to become available then her organization could ensure that voucher nonprofits would be set-up quickly in many additional states. “We basically can take a package and give it to somebody to work with and they can get it started and up and running in a very short amount of time…it would be coverage in some of those 25 states that don’t have any kind of choice right now, so they would be equipped and ready to expand and go statewide.”28 She continued to describe how in states where there wasn’t someone who wanted to start their own voucher nonprofit, her organization could even act as the SGO.

There are several loose restrictions placed on voucher nonprofits/SGOs in the EOA. First, the SGO must be considered a section 501(c)(3) nonprofit and exempt from tax under section 501(a) of the federal tax code. Second, the organization can provide grants only to schools that charge tuition and comply with all applicable State laws, including laws relating to unlawful discrimination, health and safety requirements, and criminal background checks of employees. Third, participating schools must agree to provide annual reports to the SGO and to parents of students receiving a scholarship about the student’s academic achievement compared to her peers in the same grade or school who receive a scholarship and disaggregate either state test scores or nationally norm-referenced test results by race, ethnicity and grade level. Fourth, the SGO cannot funnel funds to only one school or one student; it must distribute dollars to more than one student and to different students attending more than one school. Fifth, the SGO cannot earmark or set-aside contributions for scholarships on behalf of any specific student or group of students. Sixth, the SGO must take steps to verify the annual household income for participating students and submit to annual audits from an independent certified public accountant to demonstrate appropriate accountability for the funds.

While at first blush it may seem like there are quite a few appropriate safeguards for taxpayers and students, it is worth taking a closer look at these provisions. For example, a requirement that a school receiving money from a SGO comply with all applicable state laws regarding employment discrimination, abide by health and safety requirements and meet background check requirements is sensible but insufficient. While school employees are protected from discrimination, students who attend schools receiving federal and state credits are not protected from discrimination.

It is not well known that federal civil rights laws such as Title VI and Title IX of the Civil Rights Act, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act do not apply to private schools which receive federal funds.29 Moreover, there are more subtle ways private schools can limit who they accept and reject that state laws do not prohibit. Private schools subsidized via tuition tax credits can reject students who are performing below grade-level, or who have had trouble learning English, or who have a disability. There are few states that prohibit a private school from denying a student admission because of their religion or because they, or members of their family may be gay. Despite receiving federal subsidies, SGOs can choose to work with whatever schools they see fit, so a SGO can work exclusively with schools that use creationism as part of their curriculum or that promote ultra-orthodox Jewish practices. It would also allow SGOs to send students and funding to private schools that are not accredited by the state, which renders a diploma a student receives from the school essentially useless. The absence of a requirement that K-12 private schools receiving federal funds be accredited is in stark contrast to the requirements that higher-education institutions that receive federal funds be accredited.30

While it may appear the testing provisions in the bill give parents important information about whether their child is learning, this information is very incomplete compared to what parents would receive in the public-school system. Research is well-established that students who leave the public school system and opt for a private school voucher frequently fare worse academically.31 This bill allows private schools to give a student a different test (a norm-referenced national test) instead of the state-test taken by her peers in the public school system, which could make it very difficult for a parent to judge whether she is learning more than her peer in public school. While this bill would force the nine states that do not require state-testing to test their voucher nonprofit-bankrolled students in some form or fashion, parents would still be missing valuable information about how their children are faring academically. For example, do students receiving a TTC voucher graduate at the same rate as their peers? Do they attend college? Are they disciplined at the same rate as their peers? Are they taught by teachers with advanced degrees and subject-matter expertise? Do they have access to specialized instructional support personnel like therapists and nurses to ensure they can be educated alongside their peers? This is just a sampling of questions that private schools have no obligation to answer for parents.

Another major difference between most state TTC laws and the federal proposal is that there is no requirement that a child attend public schools prior to accessing a voucher to attend a private school. These requirements are typically intended to ensure that parents can first see how the public school system will serve their child before tapping into a new revenue stream that allows them to receive a subsidized private education. They are also meant to cut down on unnecessary public subsidies to families that would have enrolled their children in private school even without the program, perhaps with the help of financial aid from the private schools themselves. This bill runs the risk of undermining efforts by private schools to subsidize the education of their less wealthy students because it automatically provides those subsidies via publicly funded tuition tax credits even in cases where public funding may not be needed.

The requirement that bars a SGO from earmarking a donation for a particular child or private school is a welcome accountability provision, since this is not the case in several states with TTCs.32 But there is nothing to stop one family from receiving multiple scholarships from several SGOs in the state. As Stephen Sugarman of UC Berkeley Law School explains, this means that “it would be legally possible for a child to win a full scholarship at a high cost elite private school and, hence, indirectly obtain government financial aid well beyond what is now being spent on that child in public schools.”33

While this legislation requires SGOs to submit to annual audits from an independent certified public accountant and submit those audits to the Secretary of Education, there is nothing to suggest that they will lose the ability to continue operating if they fail the audit. Moreover, there is no transparency required of the SGOs to detail their process for bundling donations or how they decide how much money a student is eligible to receive.

SGOs are also allowed to keep 10% of the funds they receive for administrative costs. For a SGO that receives millions of dollars in donations this 10% administrative set-aside could prove to be quite a windfall. In Arizona, for example, the Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization received almost $73 million in donations from 2010-2014. Using that money, they paid their executive director (who also happens to be the State Senate President) an annual salary of $125,000 and then paid him a further $52,000 to rent office space that he owns, and another $636,000 to his for-profit company for processing donations and applications.34 Self-dealing of this type would be permissible nationwide under the EOA.

Part 4: The Shortcomings of Tuition Tax Credits

Allowing certain taxpayers to opt out of funding an institution as fundamentally important as the nation’s public school system erodes the public’s level of investment in that institution–both literally and figuratively.

Draining Funding for Public Schools

Although proponents maintain that tuition tax credits do not involve public money, in reality these credits are a roundabout way of providing public funding to private schools. Instead of directly funding private school scholarships, the government reimburses wealthy taxpayers (with tax credits and deductions) in return for providing funding to private schools on the state’s behalf. The end result is the same as under a direct voucher program: a boost in resources for private schools and a reduction in resources for public education and other services.

While the largest budgetary impacts of TTCs are felt at the state level, the IRS’ lax oversight of TTC programs, whereby it enables a voucher tax shelter, is also lowering federal revenue collections that could be used to support public schools. The prospect of a more financially penetrating scheme like the proposed federal tuition tax credit program, coupled with growing state tuition tax credits, could prove increasingly detrimental to federal and state funding of the public school system used by most Americans.

School districts on average receive roughly 10% of their funds from the federal government and these funds have become increasingly vital as state support for education has waned.35 According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 35 states provided less overall state funding per student in the 2014 school year than in the 2008 school year, before the recession took hold.36 The impact of these cuts could soon be compounded by federal cuts, as the FY2018 budget from the Trump Administration recommends a 13% cut to the Department of Education.37 The EOA would further exacerbate federal revenue constraints. TTCs are often not subject to the same budgetary oversight as ordinary spending on public education. Most notably, once a TTC is enacted into law it typically continues indefinitely without reexamination as part of the appropriations process. While most states subject TTCs to an aggregate budgetary cap, these caps are often structured to allow for growth that far outpaces other areas of the budget. The cap on one of Arizona’s credits for corporate taxpayers, for instance, is currently growing at a rate of 20% per year.38 Notably, the EOA under consideration in Congress would be uncapped, meaning that federal support given to private schools through this program would function more like an open-ended entitlement program than like the traditional appropriations that public schools receive.

Failing to Improve Student Achievement

Recently, there is increased evidence that leaving the public school system for a private school subsidized through a voucher program does not increase a student’s likelihood of academic success. In fact, studies in Louisiana,39 Ohio40 and Indiana41 determined that test scores have declined by considerable margins for students who participated in those states’ voucher programs. Similarly, an evaluation of the Florida TTC program42 found that students receiving TTC vouchers saw no meaningful gains in their standardized test scores and that low-income students who participated in Florida’s TTC program only to later return to public schools fared worse than similar low-income students who stayed in public schools.

Public Funding of Religion

The conservative think-tanks that conceptualized TTCs did so largely to circumvent state constitutions. Lawmakers in at least eighteen states are constitutionally forbidden from spending taxpayer dollars on religious schools.43 Since religious schools account for more than three-fourths of all elementary and secondary private school enrollment, these bans represent a major impediment to the public funding of private schools in general.44

Religious schools typically do not separate their academic programs from their religious instruction, making it difficult to prevent a publicly funded voucher from paying for religious activities and education. This poses a potential problem for religious freedom, as it means that vouchers paid for with taxpayer dollars run the risk compelling citizens to furnish funds in support of a religion. While parents certainly may choose a religious education for their children, insisting that the taxpayers pay for that education is more problematic.

Rather than directly challenge state bans on the public funding of religious schools, voucher proponents in some states have opted to sidestep them by forgoing direct funding of religious schools in favor of handsomely rewarding their wealthy residents with tax credits to spur them to fund those schools on the state’s behalf. While some judges have questioned this legalized laundering of public funds, most courts have said that this small degree of separation between public coffers and religious schools is enough to resolve the constitutional issues involved.

Leaving Low-Income Families Behind

TTCs also fail in their mission of providing true choice to low-income families. The Florida tax credit, which is one of the largest programs in the country, has an average voucher offering of $5,458.45 According to the Nation Center for Education Statistics, the average price of a year of private elementary school is $7,770, and the average annual cost of private high school is $13,030.46 While this voucher may make a difference for a family of four earning $60,000, a single mom earning $28,000 may not be able to afford the portion of her child’s tuition bill not covered by the scholarship, plus pay for uniforms, transportation, and other costs not covered by the voucher. This makes it highly unlikely that impoverished families in socio-economically segregated neighborhoods can take advantage of the vouchers. A 2003 study of Arizona’s tax credit program, for example, found that it contributed to increased economic stratification in the school system because “the state’s wealthiest students [were] likely receiving most of the tuition tax credit money.”47

Part 5: The Role of Elected Officials

Ensuring that schools have the resources they need to advance educational attainment for all students means that Congress must close the existing voucher tax shelter loophole and forgo the creation of a new TTC at the federal level. Legislation should be introduced that would specifically bar any federal charitable tax deduction for contributions to voucher nonprofits that were already reimbursed with a state tuition tax credit. This legislation could be attached to any tax reform package that advances in Congress. Furthermore, members of Congress should reject a federal tuition tax credit proposal like the Educational Opportunities Act. This legislation will not benefit low-income students, will not improve academic achievement, will not protect students from discrimination, will not be transparent and accountable to taxpayers, will undermine funding for public schools across the country, and will enable corporations and successful investors to turn a profit by showering them with tax cuts larger than the donations they make.

At the state level, elected officials must also take action to protect tax dollars and public education. Lawmakers in states with existing TTCs should scale back or eliminate those credits to put voucher nonprofits on a more even footing with other nonprofit organizations. In states such as Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Virginia where voucher nonprofits are currently being subsidized with both state tax credits and state tax deductions, lawmakers should make taxpayers choose between receiving one benefit or the other, rather than being allowed to double-dip by receiving two different state tax cuts on a single donation.48 In states without TTCs, lawmakers should resist implementing these credits given their dubious educational benefits and the fact that these credits have proven vulnerable to profiteering by wealthy individuals with savvy tax accountants.

Appendix

References

- Davis, Carl. State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education. Rep. Institution for Taxation and Economic Policy, 12 Oct. 2016. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. <http://itep.org/itep_reports/2016/10/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education.php#.WO0Lx4grJEY>.

- A 2013 poll found that 70% of the public opposes “allowing students and parents to choose a private school to attend at public expense.” Bushaw, William J. and Shane J. Lopez. “Which way do we go? The 45th annual PDK/Gallup Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward Public Schools.” September 2013. Available at: https://www.au.org/files/pdf_documents/2013_PDKGallup.pdf. Arizona may be the most prominent example of a state adopting a neovoucher program as a way to circumvent a constitutional prohibition on public funding of traditional vouchers. “Private School Tax Credits Divert Public Dollars for Private Benefits. Children’s Action Alliance. January 2016. Available at: http://azchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Private-School-Tax-Credit-brief-12-151.pdf. For additional discussion of the similarities between vouchers and neovouchers, see: Welner, Kevin. “Neovouchers’: A Primer on Private School Tax Credits.” The Washington Post. March 3, 2013. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/03/03/neovouchers-a-primer-on-private-school-tax-credits/.

- Komer, Richard D. and Olivia Grady. “School Choice and State Constitutions: A Guide to Designing School Choice Programs.” A joint publication of the Institute for Justice and the American Legislative Exchange Council. Second Edition. September 2016. Available at: http://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/50-state-SC-report-2016-web. pdf.

- Pat Toomey, U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania. Toomey’s Statement on the Vote to Confirm Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education. Pat Toomey | U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania. N.p., 03 Feb. 2017. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. Available at: https:/www.toomey.senate.gov/?p=news&id=1880.

- Internal Revenue Service, Office of Chief Counsel. Memorandum Number 201105010. February 4, 2011. Available at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/1105010.pdf.

- “Georgia Private School Tax Credit.” Georgia Private School Tax Credit. The Wood Acres School, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. <http://woodacresschool.org/private-school-tax-credit/>.

- Marotta, David John, and Megan Russell. “Education Improvement Scholarship Tax Credits.” Marotta On Money. Marotta Wealth Management, Inc., 16 Aug. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. <http://www.marottaonmoney.com/education-improvement-scholarship-tax-credits/>.

- “State of Georgia Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit Program Frequently Asked Questions.” Giving. Whitefield Academy, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. <https://www. whitefieldacademy.com/Giving/GOAL-FAQs>.

- “Donors: Do You Pay Alabama Income Tax?” Alabama Opportunity Scholarship Fund. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. http://www.alabamascholarshipfund.org/donors1.html.

- Maiorano, Michael. “Georgia Qualified Education Expense Credit: A Big Win, If You Can Get It.” TrueWealth. TrueWealth, LLC, 18 Aug. 2015. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. <http://www.truewealth.com/georgia-qualified-education-expense-credit-a-big-win-if-you-can-get-it/>.

- “School Tuition Organization (STO).” PiecefulSolutions Schools. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. https://www. piecefulsolutions.com/tuition-resources/.

- “Request 2018 Tax Credit.” Pay It Forward Scholarships. N.p., n. d. Web. 7 Apr. 2017. http://www.payitforwardscholarships. com/donate. “Frequently Asked Questions.” Pay It Forward Scholarships. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Apr. 2017. http://www. payitforwardscholarships.com/faq.

- An ITEP review found scholarship organizations advising donors that they can claim the federal charitable deduction in addition to state tax credits in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Montana, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.

- “Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit- Cap Reached 2017.” Georgia Department of Revenue. January 12, 2017. https://dor.georgia.gov/sites/dor.georgia.gov/files/related_files/document/LATP/Public%20Notice/2017%20 QUALIFIED%20EDUCATION%20EXPENSE%20TAX%20 CREDIT%20-%20Cap%20Reached%20-%20DOR%20 Website%201-12-17.pdf

- E-mail from Karen Jacobs, Arizona Department of Revenue. August 30, 2016. See also: Rhode Island Division of Taxation. “Tax Credits for Contributions to Scholarship Organizations.” Accessed October 7, 2016. Available at: http://www.tax.ri.gov/Credits/index.php.

- Slade, David. “S.C. tax rule creates a way to profit by funding private school scholarships.” The Post and Courier. July 13, 2014. Available at: http://www.postandcourier.com/article/20140713/PC05/140719981.

- The corporate AMT faced by C corporations does not allow for the same type of gaming described in this report.

- IRS Statistics of Income data for Tax Year 2014 indicate that 82% of returns owing AMT, and 93% of dollar raised via the AMT, are associated with this group. Taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $500,000 per year are most likely to be affected by the AMT, with 61% of this group owing some amount under the levy. By comparison, 45% of taxpayers earning between $500,000 and $1 million owe some amount of AMT, as well as 19% of taxpayers earning over $1 million.

- “Florida Tax Credit Scholarships.” Florida Department of Education. Available at: http://www.fldoe.org/schools/school-choice/k-12-scholarship-programs/ftc/. Accessed October 7, 2016.

- State of Montana. (n.d.). Education Donations Portal. Retrieved from https://svc.mt.gov/dor/educationdonations/SSOHelp.aspx.

- “Louisiana – Tuition Donation Rebate Program.” EdChoice. Friedman Foundation for Educational Coice, n.d. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/louisiana-tuition-donation-rebate-program/’ and https://dor.sc.gov/exceptional-sc

- Marcavage, Whitney R. 2016/17 SCHOOL CHOICE REPORT CARD. Rep. American Federation for Children, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. <http://www.federationforchildren. org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/AFC_2016_ reportcard2.1_hires.pdf>.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Emma, Caitlin. “What to Watch as Congress Dives into Tax Reform.” Politico Morning Education. Politico, 29 Mar. 2017. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. <http://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-education/2017/03/what-to-watch-as-congress-dives-into-tax-reform-219485>.

- Married individuals filing separate tax returns would be able to receive a maximum credit of $2,250 per spouse, but most married couples file joint returns.

- “A $20 Billion School Choice Tax Credit Program: Yes, No, Maybe, How So?” A $20 Billion School Choice Tax Credit Program: Yes, No, Maybe, How So? Hoover Institution, Washington, D.C. 25 Apr. 2017. Speech.

- “Vouchers Undermine Civil Rights.” NCPE Voucher Facts. National Coalition for Public Education (NCPE), n.d. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. <https://www.ncpecoalition.org/lose-rights>.