This post and the data available for download have been updated to reflect an amendment adopted before the committee approved the Economic Mobility Act.

Download national and state-by-state estimates of EITC and CTC provisions.

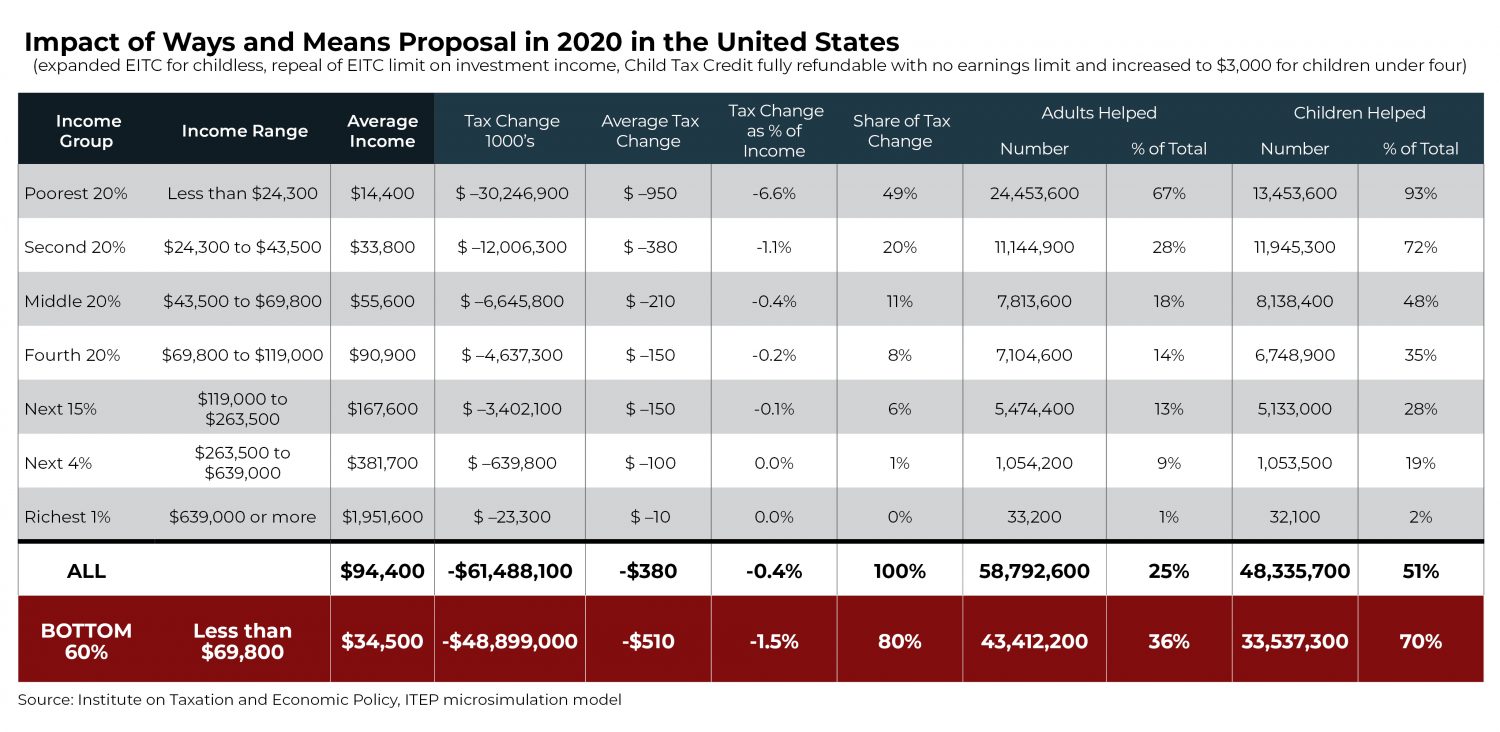

On Thursday, the House Ways and Means Committee approved the Economic Mobility Act of 2019, a bill introduced by Chairman Richard Neal to expand some key tax credits to help low- and moderate-income people and families. New data generated with the ITEP microsimulation tax model show how adults and children would benefit nationally and in each state.

One provision would expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for adults without children living with them. The EITC is supposed to ensure that working people do not live in poverty, but under current law, the maximum EITC for childless adults is just a little more than $500. Low-income childless adults are the only people who can be taxed further into poverty under current law.

Another provision would repeal limits in the Child Tax Credit (CTC), which prevent low- and moderate-income families from claiming the full credit. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) increased the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 per child but capped the refundable portion, which is the part of the credit that benefits low-income families, at $1,400 per child. TCJA also maintained another provision that limits the refundable part of the credit to a percentage of earnings above a certain threshold, which prevents those with no or low earnings from accessing the full credit.

Families with low earnings pay federal payroll taxes and state and local taxes, but often earn too little to owe any federal income taxes. For a family in this situation, a tax credit can only be helpful if it is refundable, meaning it can result in negative income tax liability. Refundable tax credits such as the EITC and CTC are motivated by the idea that there is no reason for the tax system to tax the poor or the near-poor further into poverty. Instead, the tax code can do the opposite and lift people out of poverty and provide greater financial security.

Before passing the bill, the committee adopted an amendment that increases the CTC from $2,000 to $3,000 for children under the age of four.

The Economic Mobility Act targets help to those who need it. In 2020, 80 percent of the benefits of these EITC and CTC changes would go to the bottom 60 percent of Americans.

These provisions would be particularly helpful to the poorest fifth of Americans. Among this group, these changes would help 67 percent of adults and 93 percent of dependent children.

The bill also includes an expansion of the Child and Dependent Care Credit, which ITEP is not yet able to estimate. That provision would expand the credit and make it refundable. Under current law, it is virtually impossible for a poor family to benefit from it despite the serious need to assist low-income families with childcare and care for other dependents.

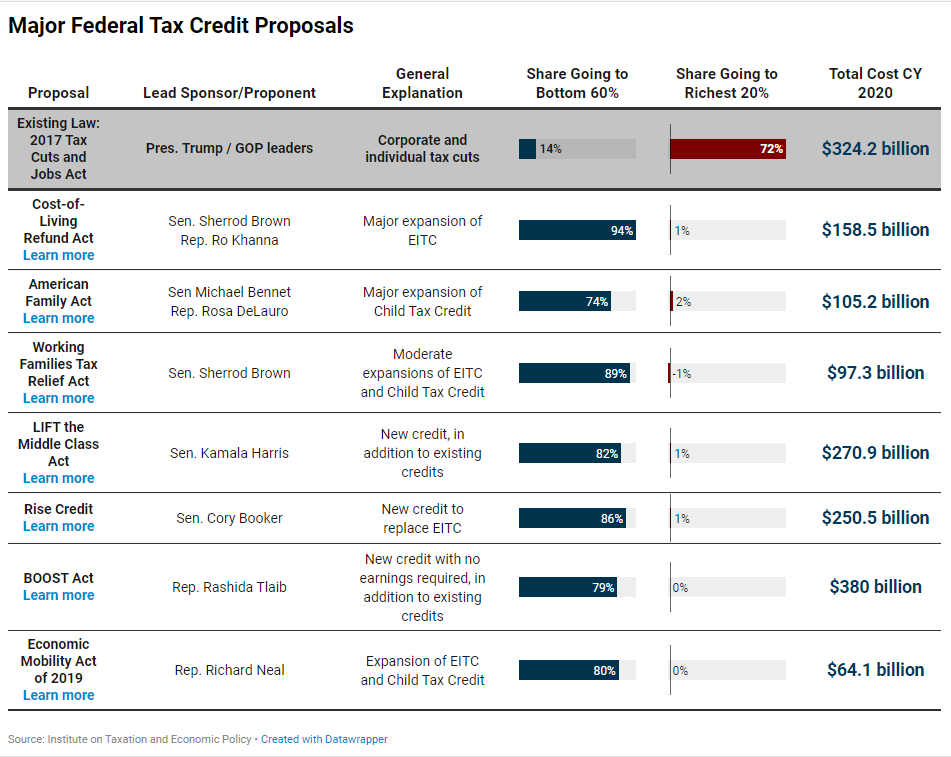

In May, ITEP released a report estimating the impacts of five proposals that would significantly expand refundable tax credits or create new ones. The Economic Mobility Act is less ambitious than these proposals but similar in that the distribution of its benefit is almost the reverse of TCJA. The 2017 law provides most of its benefits to the richest fifth of Americans and provides significant benefits to foreign investors. Like the five proposals we examined in our May report, the Economic Mobility Act provides nothing to foreign investors and relatively little to the richest fifth of Americans. Instead it focuses on the bottom 60 percent of Americans.

Prospects for the Economic Mobility Act are unclear right now. The bill may be attached to other legislation that would extend several tax breaks for businesses and accelerate the expiration of the estate tax cuts under TCJA. But the bill nonetheless illustrates a growing trend in favor of tax policies that are starkly different from TCJA.