(Download state-by-state data)

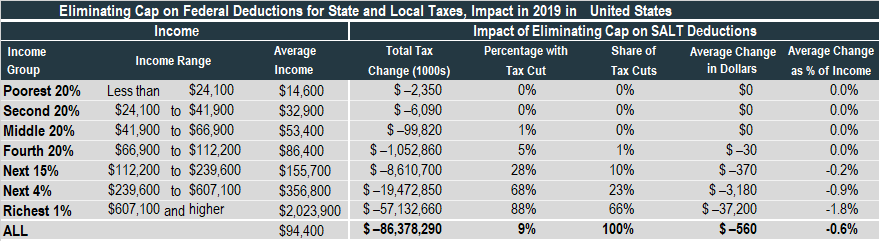

A bipartisan proposal in Congress to eliminate the new $10,000 cap on federal deductions for state and local taxes (SALT) would cost more than $86 billion in 2019 alone and two-thirds of the benefits would go to the richest 1 percent of households. Unfortunately, “work around” proposals in some states to allow their residents to avoid the new federal cap would likely have the same regressive effect on the overall tax code.

Before 2018, taxpayers could deduct their state and local taxes from the income they report on their federal tax return, and for most people these deductions were not limited in any significant way. The bulk of these deductions were claimed by relatively well-off people. In fact, the new $10,000 cap on SALT deductions is, taken on its own, a progressive change. The problem is that Congress used the cap to pay for tax cuts that are even more targeted to the very rich – such as tax cuts for corporations, pass-through businesses, and large estates, to name a few.

The bipartisan bill introduced last week by Reps. Nita Lowey and Peter King from New York would remove the cap on SALT deductions while leaving the other provisions of the Trump-GOP tax law in place. The main result would be to provide well-off households with even larger tax breaks than they have already received under the new federal tax law.

Even in the states that are thought to be hit the hardest by the cap on SALT deductions, it turns out that removing the cap would mainly help the well-off. The seven states most affected by the cap on SALT deductions are California, Connecticut, DC, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York. Using the ITEP microsimulation model, we estimate that more than half of the benefits of the Lowey-King bill would go to the richest one percent in each of these states except for Maryland (where 47 percent of the bill’s benefits would go to the richest one percent of state residents). In California, Connecticut and New York, more than 60 percent of the benefits would go the richest one percent of state residents. In these seven states, the richest five percent of residents would receive between 75 percent of the benefits (in Maryland) and 86 percent of the benefits (in New York). (Download state-by-state data.)

Which raises the question: Why exactly should lawmakers rush to change tax law in a way that would mainly help the richest households? These are the very groups that benefited the most from the Trump-GOP tax plan. How can piling on more tax cuts for these households improve the situation?

Congress is unlikely to enact the Lowey-King bill anytime soon, but some states are considering their own changes that would allow their residents to effectively avoid the $10,000 cap. As ITEP has explained elsewhere, there are many reasons to doubt that these work-around schemes are workable or even legal.

But even if these schemes could achieve their purpose — allowing state residents to avoid the cap on SALT deductions — they would still be problematic because they would have the effects described here, providing the vast majority of benefits to those who least need help, at an exorbitant cost to the nation.