Nearly 40 years ago, lawmakers in Ohio and Michigan sought to give the automobile industry a boost by exempting car purchases from sales tax. There’s no definitive research on whether this temporarily boosted carmakers’ fortunes, but research abounds on how the industry struggled throughout the 1980s as it faced a recession, shifting consumer preferences and competition from Japanese car manufacturers. In other words, a temporary sales tax holiday in a couple of states may have helped some consumers save a bit of money on a car purchase, but it couldn’t fix the underlying structural problems that were the root of the auto industry’s problems.

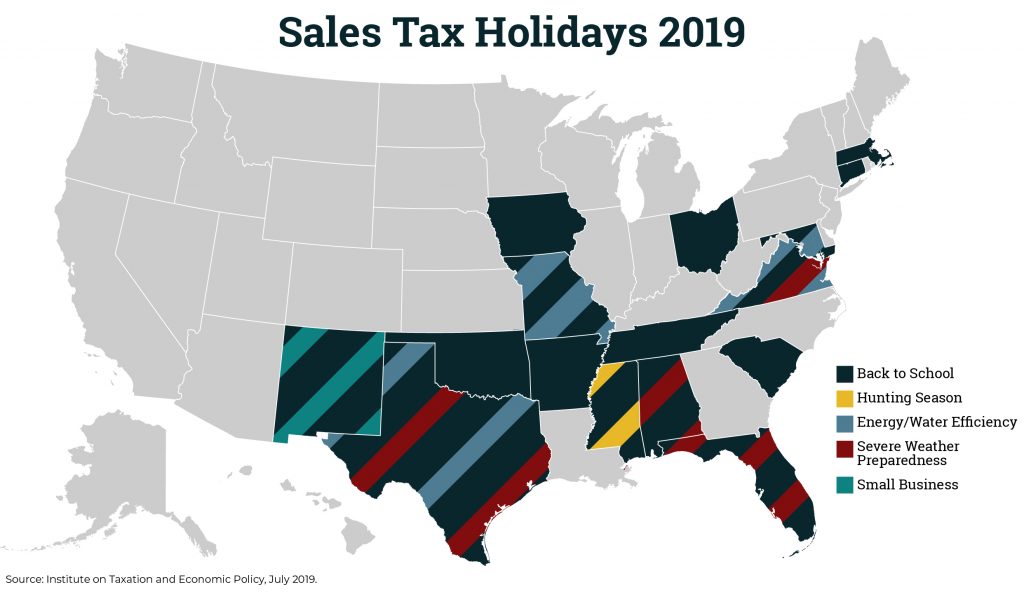

During the late 1990s, the idea of sales tax holidays spread, with 19 states holding them at its peak in 2010. This year, 17 states will hold sales tax holidays, and, like years before, a majority of them will be pegged to “back to school” season, though there are a handful of holidays for hunting, energy efficiency and severe weather preparedness. The idea, of course, is to give working families a bit of savings on necessary purchases for school and home. But just as the very first sales tax holiday for car sales did not fix the auto industry’s challenges, providing consumers a temporary reprieve on sales tax will not address families’ pocketbook concerns.

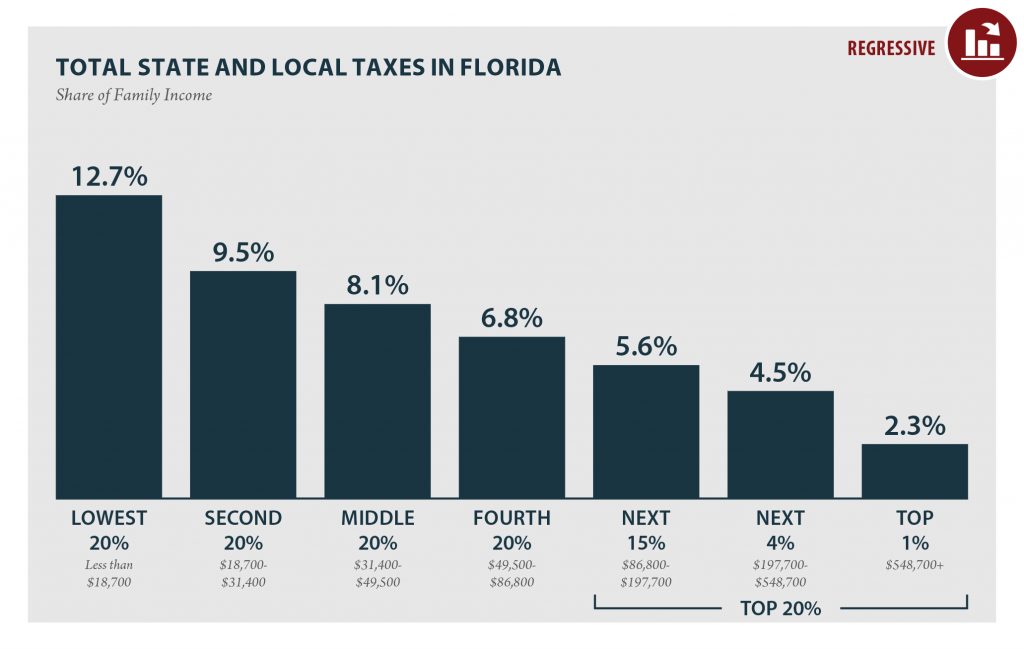

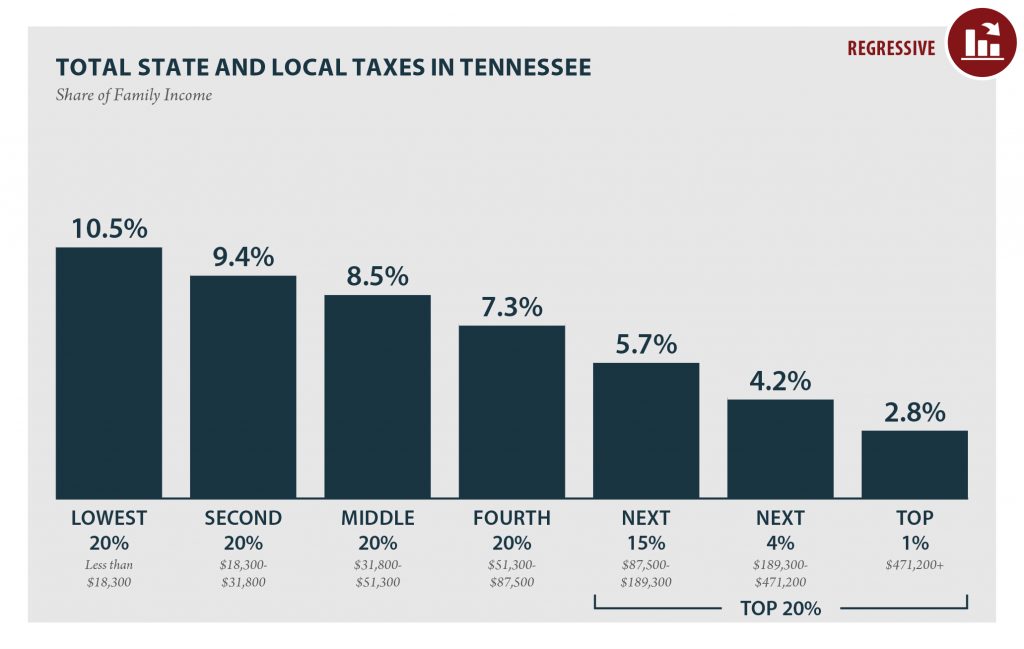

ITEP’s updated sales tax holiday research brief, Sales Tax Holidays: An Ineffective Alternative to Real Sales Tax Reform, outlines the problems with sales tax holidays. Chief among them is that a two- or three-day sales tax holiday doesn’t reduce taxes for low- and moderate-income families the other 362 days of the year. Most state tax codes (45 out of 50) are regressive, meaning they tax lower-income families at a higher rate than wealthier families. Part of the reason for this is that many states rely heavily on regressive sales tax to raise revenue. In fact, all states that will hold a sales tax holiday this year have upside-down tax systems, charging their poorest 20 percent a higher average effective rate than their top 1 percent.

Furthermore, some of the most egregious offenders don’t assess any state income tax (which can be structured more progressively) and have comparatively high sales tax. Florida, Tennessee and Texas, for example, all rank in the bottom 10 on ITEP’s Inequality Index. All will hold sales tax holidays this year. None assess an income tax. All place a disproportionately high effective tax rate on their lowest-income taxpayers. In Florida, the poorest 20 percent pays an average effective tax rate of 12.7 percent v. 2.3 percent for the top 1 percent. In Tennessee, the disparity is 10.5 percent v. 2.8 percent, and in Texas, it’s 13 percent v. 3.1 percent. These states’ sales tax holidays will not fix their upside-down tax codes.

The brief outlines how sales tax holidays are poorly targeted: “Wealthier taxpayers are often best positioned to benefit from the holidays since they have more flexibility to shift the timing of their purchases to take advantage of the tax break—an option that isn’t available for families living paycheck to paycheck.”

The bottom line is that sales tax holidays are a novel experiment that long ago ran its course. It’s telling that a majority of states have not had these holidays and other states have repealed theirs. Forty years ago, a sales tax holiday on the purchase of an automobile could not boost the auto industry. It took other fundamental changes to reverse the industry’s fortunes. The same is true for working families—the purported target of sales tax holidays. Saving a few dollars on school supplies or a home generator purchase will not change the fact that most state tax systems assess a higher tax rate on low- and moderate-income families than the top 1 percent.