Yesterday the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee advanced a bill (H.R. 9462) that would create an unprecedented tax incentive designed to fund private, mostly religious, K-12 schools.

The incentive would be a tax credit at least three times more generous than what people can claim for donations to other causes, like supporting American veterans or survivors of domestic violence. Shockingly, the incentive would be so enormous that taxpayers donating corporate stock to these private school programs would receive more back in tax cuts than they donated. After this wasteful feature of the bill was criticized in committee and confirmed by an expert witness, Republicans voted down a carefully tailored amendment that would have closed the tax shelter while leaving the rest of the bill intact.

While there was never any question as to whether the committee’s majority supported private school vouchers, this is the first time they have gone on the record specifically endorsing the kind of profitable tax shelter embedded in many voucher programs. As we learned yesterday, most of the House Ways & Means Committee is content to facilitate new forms of wasteful tax avoidance if doing so aids the cause of funneling more public resources into private K-12 schools.

Anatomy of the Tax Shelter

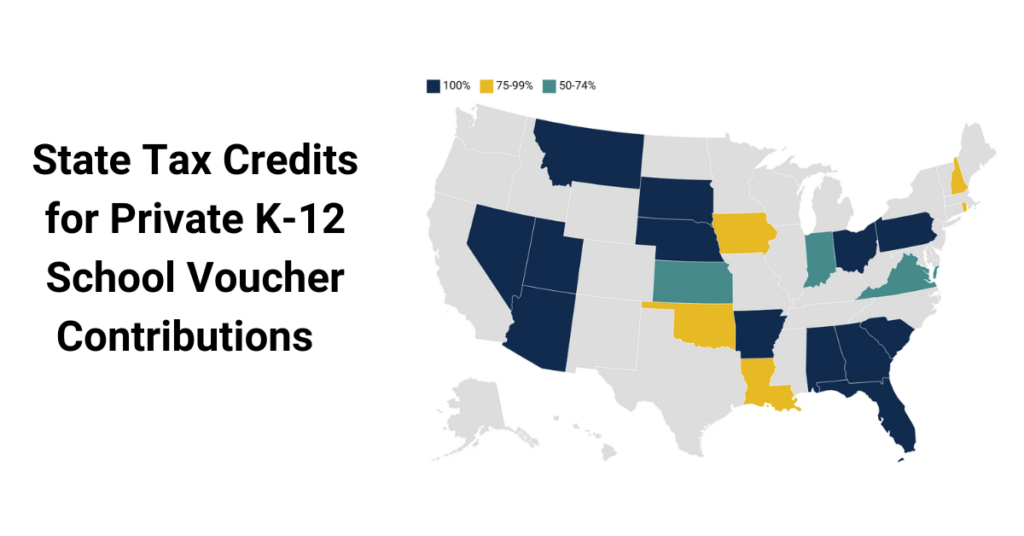

The basic design of H.R. 9462 follows the template set forth in model state legislation that the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) has succeeded in shepherding into enactment in more than 20 states. At its core, the policy funnels public tax dollars into private K-12 schools using two different intermediaries (wealthy donors and voucher-bundling organizations) to obscure this flow of funds. This is accomplished by paying out large tax credits, worth 100 percent of the amount donated, to people who send money or corporate stock to organizations that bundle those dollars into vouchers that fund the operation of private K-12 schools.

Paying out a 100 percent federal match on these amounts, up to a maximum of 10 percent of income for most taxpayers, is a highly questionable policy with no parallel in federal tax law. Donations to other nonprofit organizations are only eligible for a federal match, or tax deduction, worth up to 37 cents per dollar donated.

The proponents of this bill, however, seem to think that even a 100 percent match is not enough. Tucked away in section 25E(c)(2) are three words— “or marketable securities”—that turn the credit into a 120 percent match or more for upper-income families seeking to offload corporate stock.

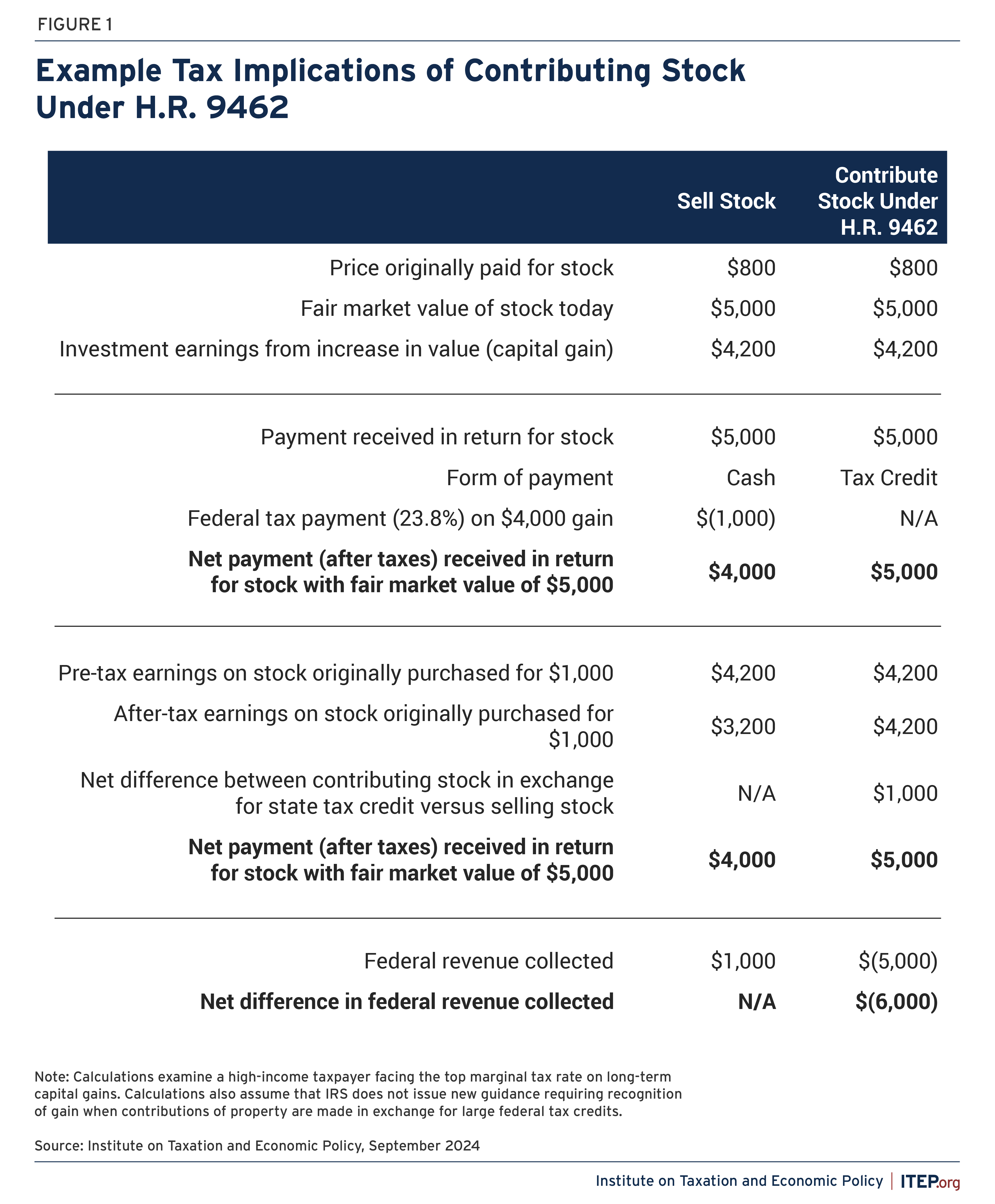

As illustrated in Figure 1, a taxpayer contributing corporate stock worth $5,000 that they initially acquired for a price of $800 would be able to double dip with two federal tax benefits: the $5,000 tax credit at the heart of the bill, plus the ability to avoid paying any capital gains tax on the $4,200 of investment income that this stock generated. Stacking these two federal tax benefits results in a federal revenue loss of $6,000 from this contribution, relative to what would have been collected if the taxpayer had sold their stock rather than given it to the voucher bundling organization to sell. Put another way, the federal government would be forgoing $1.20 in tax revenue for every $1 given to support private schools—with the 20-cent excess falling into the pockets of wealthy individuals. Avoidance of state-level capital gains tax would add further to the profit margin available to most potential contributors, and in practice the average contribution is likely to far exceed $5,000 per year.

Committee Discussion of the Shelter

In fairness to the committee, the operation of this tax shelter is somewhat complicated, and it is possible that some members were initially unaware of its presence in the bill. But if they were unaware of it prior to this hearing, they lost any claim to plausible deniability yesterday. Representatives Doggett, Moore, and Thompson went to great lengths to explain the tax shelter to their colleagues. Crucially, their understanding of the shelter was also confirmed by Robert Harvey, Deputy Chief of Staff for Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, when he explained that “there’s no capital gains tax” on stock contributed under this program.

Later in the hearing, Rep. Thompson praised a feature of the bill meant to prevent another form of double dipping where taxpayers could potentially claim the credit in combination with a federal charitable deduction, enabling them to turn a profit. He went on to note, however, that “there’s still plenty of ways for taxpayers to contribute $100 and end up with more than $100 in their pocket” before offering a narrowly drafted technical fix that would prevent capital gains tax avoidance and, in addition, foreclose on the possibility of other kinds of double dipping if states change their laws in the future. As Rep. Thompson explained, “the bill is creating a loophole where wealthy taxpayers most certainly will take advantage of, and this committee should nip that in the bud before this bill ever becomes law.”

A Policy Geared Toward the Wealthy

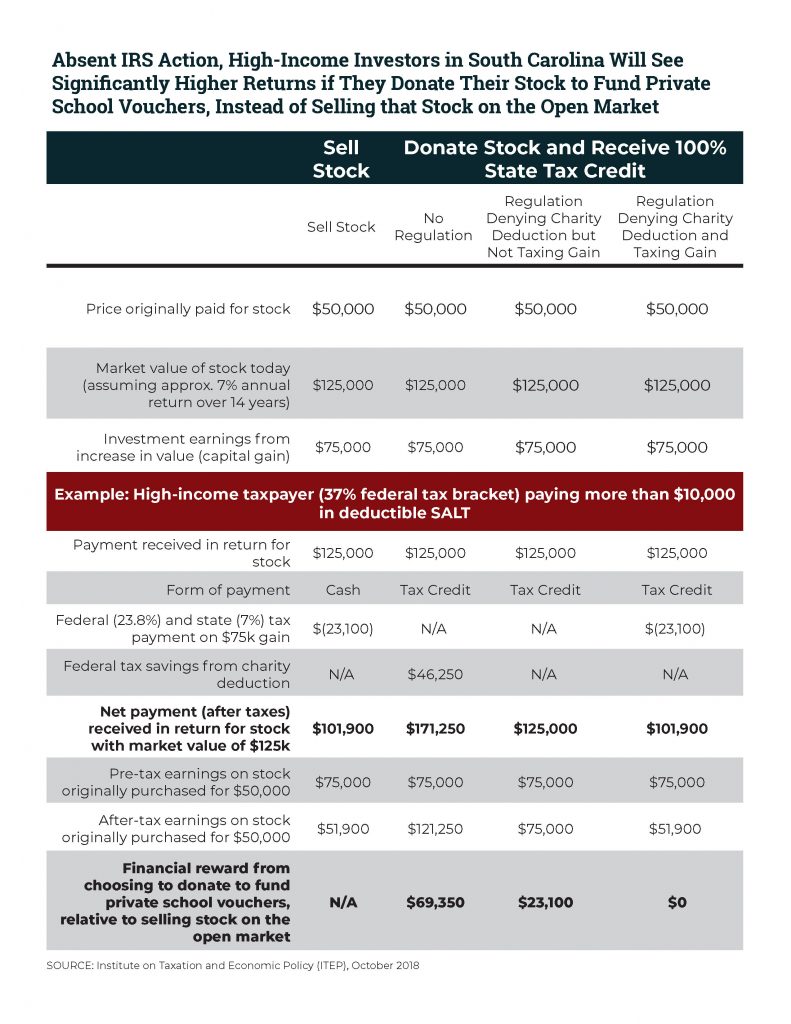

Critics of this tax shelter are right to suspect that it will primarily benefit wealthy families, as people with substantial corporate stock holdings will find the proposal’s tax shelter the most enticing. If the bill were to become law in its current form, and if the IRS failed to respond with the kind of regulation that ITEP and other organizations have urged to crack down on similar tax shelters in the states, then it would set off a frantic annual application process where people seeking to offload some of their stock holdings would rush to do so tax-free through this program.

The importance of acting quickly would be paramount because the legislation would cap tax credit payouts at $5 billion per year, allocated on a first come, first served basis. As we’ve seen in the states, while 100 percent tax credits sometimes fail to attract the level of donations that proponents had hoped for, once the payouts push past 100 percent and into the realm of profitability, interest in these programs surges as opportunists with little interest in private K-12 schooling jump at the chance to make a buck.

Note: This article has been updated to better reflect the proposed cap on tax credit claims per taxpayer, which for most taxpayers is 10 percent of adjusted gross income.