For much of the last century, estate and inheritance taxes have played an important role in fostering strong communities by promoting equality of opportunity and helping states adequately fund public services. While many of the taxes levied by state and local governments fall most heavily on low-income families, only the very wealthy pay estate and inheritance taxes.

Changes in the federal estate tax in recent years, however, caused states to reevaluate the structure of their estate and inheritance taxes. Unfortunately, the trend of late among states has tended toward weakening or completely eliminating them. But this need not be so; states can restore or improve their estate and inheritance taxes as a vital progressive revenue source to support services and communities while also protecting the source from the whims of federal lawmakers. This policy brief explains state inheritance and estate taxes, discusses recent state trends and policy decisions that have impacted the taxes, and explores how states can adopt or strengthen these important components of a progressive tax structure.

The Long History of Estate Taxes

Until 2001, levying a tax on the transfer of wealth from one generation to the next was one of the few things all fifty states could agree on. A century ago, the federal government enacted an estate tax to “break up the swollen fortunes of the rich,” and every state followed suit, enacting a similar tax of its own. While these taxes typically represent only a small portion of overall state tax collections, estate taxes (which are paid by taxable estates upon death) and inheritance taxes (which are paid by individuals who receive gifts from estates) play an important role in reducing the transfer of concentrated wealth from one generation to the next. This function is now more important than ever: in 2012, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans owned 42 percent of the wealth nationwide—more than the poorest 90 percent combined.

How the Federal Estate Tax Works

The federal estate tax was designed to apply only to the wealthiest Americans—and that is exactly what it does. In fact, the percentage of deaths in the U.S. resulting in federal estate tax liability was only 0.2 percent—just two out of every one thousand deaths—for deaths occurring in 2014 and owing tax in 2015 (estate taxes are usually filed the year after a person dies). The small number of Americans liable for the tax is largely the result of a long-running trend toward weakening it at the federal level. After President George W. Bush’s 2001 tax cut package authorized the gradual repeal of the federal estate tax by 2010, President Barack Obama and Congress agreed in 2011 to reinstate the tax with a basic exemption of $5 million—the highest level ever—indexed to inflation. As part of the “fiscal cliff” deal enacted in 2013, that higher exemption level was made permanent.

The basic exemption, throughout history, existed to exclude low- and middle-income households from the estate tax, ensuring that only those estates valued at higher than the exemption level are subject to tax. Today, the steep 2017 exemption threshold of $5.49 million ($10.98 million for married couples who take advantage of estate tax “portability”) effectively exempts many wealthy estates from taxation as well. By comparison, during the decade prior to the Bush tax cuts, the exemption level hovered within the $600,000 range and the percentage of estates subject to tax was as high as 3 percent.

For the few wealthy estates that are larger than the exemption amount, the structure of the tax provides for multiple deductions that serve to lower the amount of the taxable estate (and therefore slash tax liability even further), including funeral expenses, mortgages and other debts, bequests to surviving spouses, and charitable donations. Family farms and small businesses are also eligible for additional value reductions to ease concerns that they could be impacted by the tax (an extremely unlikely scenario given the current high exemption amount). After subtracting the exemption and these various deductions, a tax rate of 40 percent is applied to the remaining net value of any qualifying estate.

How State Estate Taxes Work

The same Bush-era legislation that diluted the federal estate tax also impacted the traditional structure of estate taxes at the state level, and continues to threaten their future. Starting in 1926, the federal estate tax allowed a dollar-for-dollar tax credit against the estate taxes levied by states, up to a specified maximum amount. The credit gave states an incentive to levy an estate tax at least as large as this credit: in the states levying a “pick-up tax”—that is, a tax calculated to be exactly equal to the maximum federal tax credit—the state’s estate tax amounted only to a transfer of estate tax revenues from the federal government to the states. In other words, the pick-up tax did not change the amount of estate tax paid. Rather, it meant that part of the federal estate tax liability was being shared with, or “picked up” by, state governments.

Every state took advantage of this incentive to enact an estate tax at least as large as the pick-up tax until the 2001 Bush tax cuts phased out the federal credit. In many of the states that based their tax on the federal credit, this meant that the state’s estate tax also ceased to exist in 2005. The “pick-up tax” credit was scheduled to come back to life along with the federal estate tax in 2011, but Congress instead extended the repeal of the credit and replaced it with a deduction for two years. As a result of the fiscal cliff deal struck in late 2012, the credit was permanently eliminated and replaced with the deduction.

In the aftermath of the pick-up tax credit’s repeal in 2005, many states took steps to prevent the complete elimination of their estate tax. This happened in two ways: some states “decoupled” from the federal estate tax cut, effectively tying their own estate tax to the pick-up tax credit as it existed in 2001 prior to the repeal, while other states instituted their own separate estate or inheritance taxes. Many states which decoupled from the cut still continued to couple to the exemption levels set by the federal law; others created their own exemption thresholds.

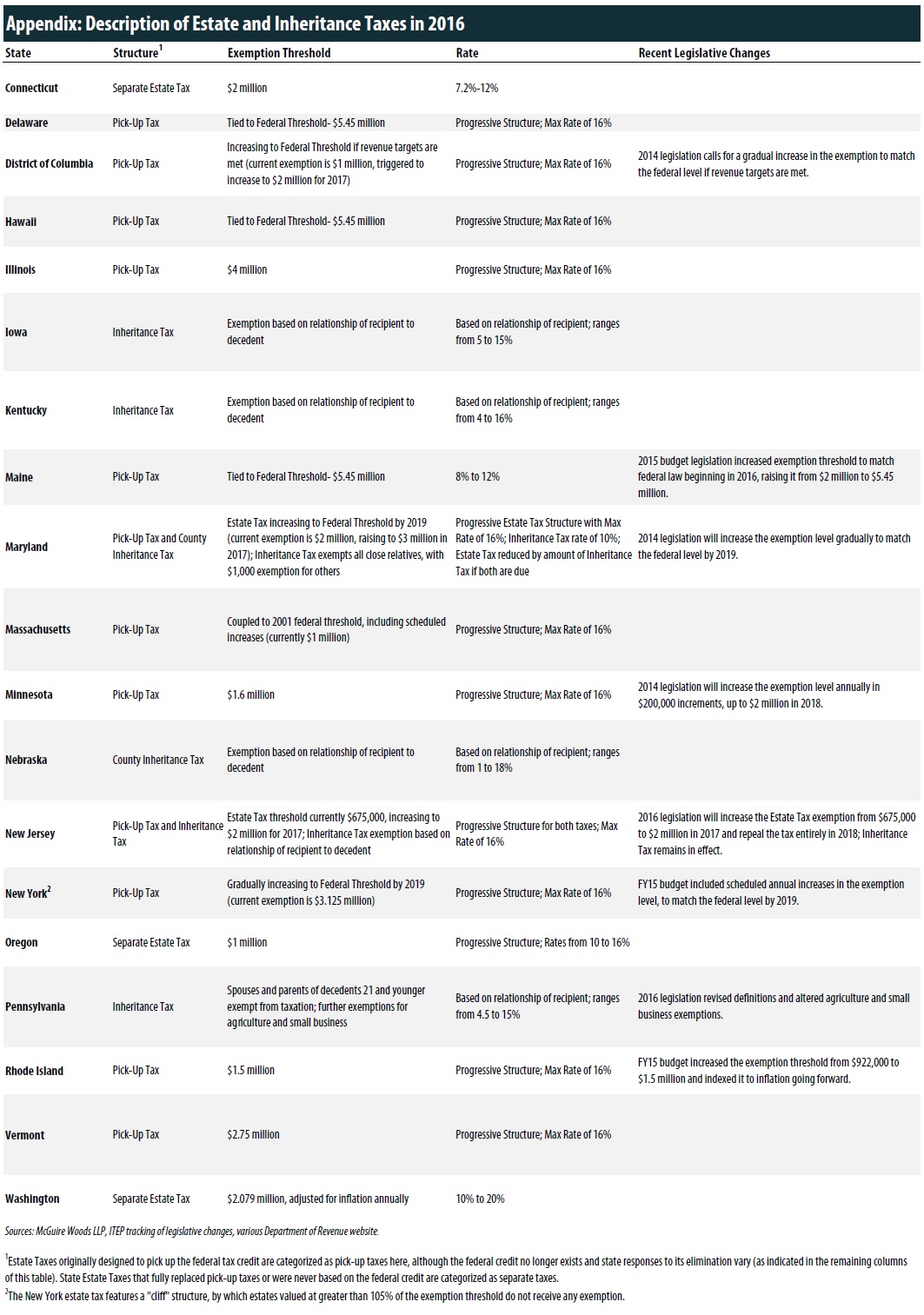

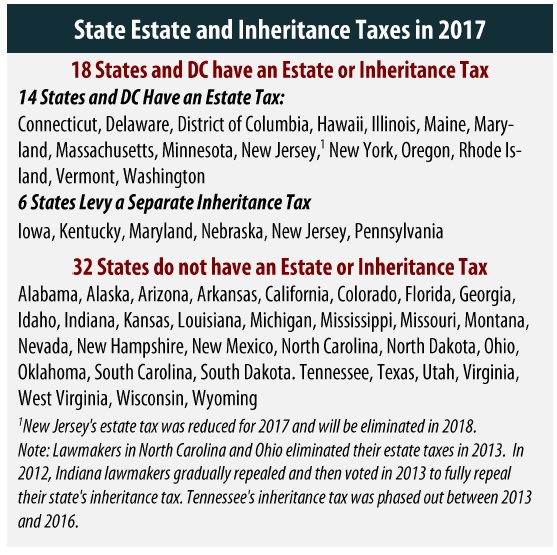

Among the states that have decoupled from the pick-up tax credit elimination but still allow the same exemption levels used in the federal tax are Delaware and Hawaii. Maine, Maryland, New York, and the District of Columbia recently enacted legislation to gradually raise their exemption thresholds to match the federal level. States decoupling from the pick-up tax credit elimination and maintaining their own exemption thresholds are Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Connecticut, Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington all maintained or created their own separate estate or inheritance taxes following the elimination of the pick-up credit (See the Appendix for details on state estate and inheritance taxes).

Options for Reform, and Recent Developments

The 32 states lacking an estate tax as a result of the elimination of the federal pick-up tax credit or more recent state legislation have a straightforward option for reintroducing this source of progressivity back into their tax structures: decoupling from the federal tax credit repeal. Using Maine, Massachusetts, or other states as models, states could achieve this by defining the state estate tax to equal the federal credit as it existed in 2001—before the passage of the Bush administration’s estate tax cuts. States taking this step will effectively have a tax with a progressive rate structure and top rate of 16 percent on estate value in excess of the exemption amount. The exemption could be set at the same level as the existing federal exemption ($5.49 million in 2017) or set at a more historically representative amount (Massachusetts currently has a $1 million exemption). States taking this step can also “piggyback” on special federal provisions that help to ensure that small businesses and family farms won’t be hit by the estate tax, including a provision assessing farmland according to its agricultural value rather than its market value, an extra exemption for family-owned businesses above the basic amount, and a provision allowing certain estates to pay the estate tax over 14 years. States should take care not to tie their estate tax laws too closely to federal statute, however, as doing so opens up the possibility that federal estate tax cuts could flow through to state tax codes as well.

Unfortunately, many states have recently gone the opposite direction. North Carolina and Ohio both eliminated their estate taxes effective in 2013, with Indiana also eliminating its inheritance tax that same year. Tennessee’s inheritance tax was phased out between 2013 and 2016. Lawmakers in Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia either increased their exemption thresholds in the past few years or passed legislation calling for future increases to be achieved by gradually coupling their exemption levels to the federal threshold or through independent legislation (See Appendix for information on recent legislative changes). Most recently, in 2016 New Jersey’s lawmakers enacted a two-year repeal of their state’s estate tax as part of a problematic deal to raise the gas tax—a levy which falls most heavily on low-income families who will not benefit from estate tax repeal. On a more promising note, Delaware took steps to preserve its estate tax in 2013 through legislation eliminating a 4-year sunset provision included in a 2009 bill which decoupled the state’s tax from the federal pick-up tax credit elimination.

Inheritance Taxes

Despite often being confused with estate taxes, inheritance taxes are slightly different mechanisms for taxing the transfer of wealth after a death. Inheritance taxes are paid not by the estate of the deceased, but by the inheritors of the estate. For example, the Kentucky inheritance tax “is a tax on the right to receive property from a decedent’s estate; both tax and exemptions are based on the relationship of the beneficiary to the decedent.” In Kentucky there are three classes of beneficiaries. If the beneficiaries of the estate are a parent, child, sibling, or grandchild or other close relation no inheritance tax is due. Nieces, nephews, aunts and other specific relations receive a $1,000 exemption and pay tax rates of 4 to 16 percent on their inheritance. Other classes of beneficiaries receive a $500 exemption and must apply tax rates between 6 and 16 percent of their gift. Inheritance taxes in Iowa, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania are similarly structured.

Final Word

The extensive concentration of wealth held by a small number of extremely wealthy families is of more concern now than perhaps ever before. Estate and inheritance taxes can help address rising wealth inequality and fund crucial investments in our communities while pushing back against efforts at the federal level to carve out tax breaks that only benefit the wealthiest Americans and undermine equality of opportunity. While these taxes typically represent a small part of overall state tax collections, they play an important role in reducing the transfer of concentrated wealth from one generation to the next—a fact that makes the recent trend toward cutting state estate taxes especially troubling. Because the federal estate tax has weakened over the last decade, states have an opportunity to take the lead on this important issue and develop or strengthen their estate and inheritance taxes.