Gas taxes are levied in every state and are an important part of how states fund their transportation infrastructure. State legislators are increasingly realizing that it doesn’t work to let gas taxes stagnate while inflation raises the cost of building and maintaining infrastructure and advancements in vehicle fuel efficiency chip away at the number of tax dollars collected. To deal with these issues, gas taxes can be reformed to better align tax revenue with the expenses that revenue is meant to fund. In the states where most Americans live, lawmakers are moving to do exactly that.

National Landscape of State Gas Tax Designs

Lawmakers can choose from three broad gas tax designs (plus the option to use a hybrid structure that employs more than one design):

- a fixed-rate tax that does not change over time (as is done in 24 states today)

- a variable-rate tax calculated as a percentage of fuel prices (8 states)

- a variable-rate tax with some connection to the cost of funding the transportation network (18 states plus D.C.)

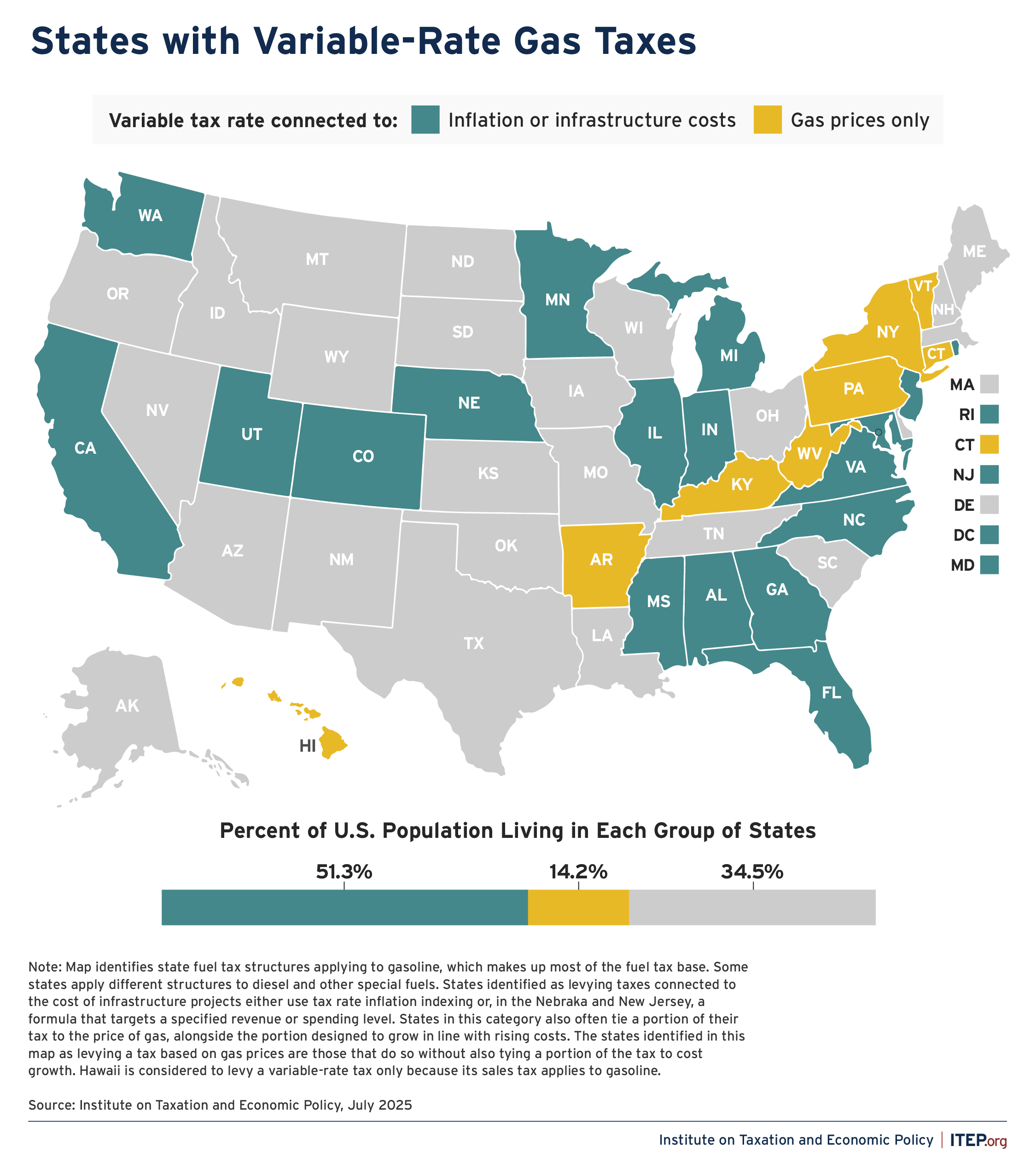

Figure 1 highlights the 26 states, plus D.C., that levy variable-rate gas taxes. It also sorts those states based on whether their gas tax structures are designed to at least partly consider cost growth over time, or whether they are connected exclusively to fuel prices.

More than 223 million people (or 65 percent of the U.S. population) live in places where the state gas tax rate automatically varies over time. Most of that group (175 million people, or 51 percent of the U.S. population) lives in a state where the tax rate has some degree of connection to the infrastructure costs confronting state governments.

Adopting variable-rate gas tax designs with some connection to infrastructure costs is an effective way to put funding for the nation’s infrastructure investments on a more sustainable course.

Fixed-Rate Taxes

Historically, fixed-rate taxes were the most common choice of gas tax structure, with the rate collected as a set number of cents per gallon. The federal gas tax has used a fixed-rate design throughout its entire history and, as recently as 2012, 36 states used a fixed-rate structure for their gas taxes as well. The popularity of this design has been waning, however, and just 24 states levy fixed-rate taxes today.

Under a fixed-rate tax, the rate does not change even when the cost of infrastructure materials rises or when drivers purchase more fuel-efficient vehicles and pay less in gas tax. As a result, the tax’s purchasing power inevitably erodes—sometimes dramatically—with each passing year. This shortcoming is the main reason that fixed-rate taxes are becoming less common in the states.

Variable-Rate Taxes on Fuel Prices

Another relatively common structure is to tie the gas tax rate to the price of fuel at either the wholesale or retail level. This design can feel familiar to lawmakers who are accustomed to sales taxes levied on the purchase price of a wide array of everyday items.

Over the long run, a variable-rate tax tied to gas prices can potentially raise revenue more sustainably than a fixed-rate tax, simply because the long-run trend is toward higher gas prices. But gas prices are notoriously volatile, and states with these structures often find that changes in the tax rate being charged from one year to the next do not align with the growing costs they face.

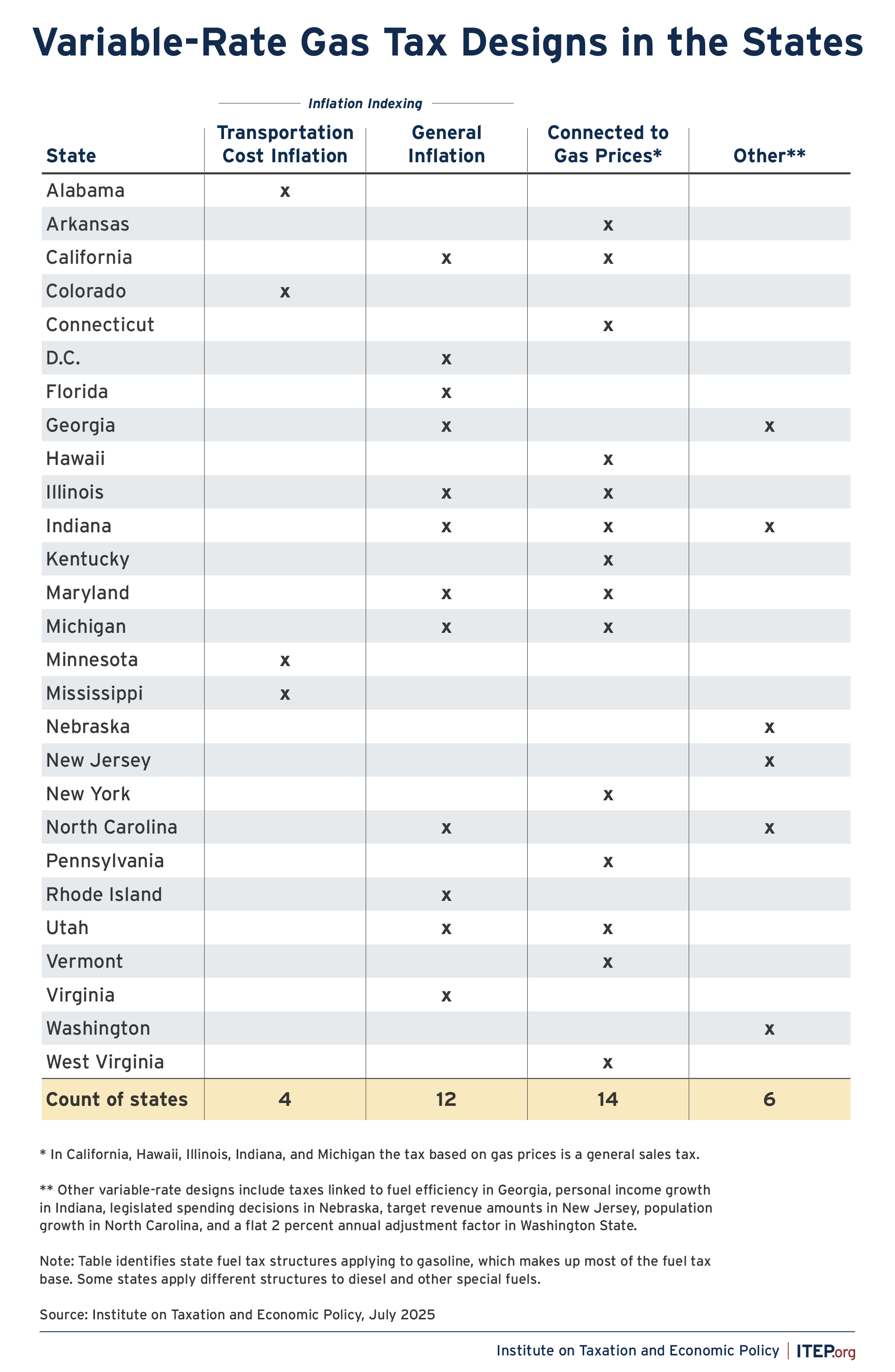

Often, states with taxes linked to the price of gas will write guardrails into their laws designed to limit volatility. While those guardrails can be useful in improving revenue predictability, the result is often a stagnant tax rate or one that bounces around within a narrow range. Today there are eight states with variable-rate gas taxes connected only to gas prices though, as seen in Figure 2, some states that use other variable-rate structures also tie a portion of their gas taxes to the price of gas.

Variable-Rate Taxes Connected to Cost Growth

A better approach is to connect a variable tax rate to some measure related to transportation construction and maintenance costs. Typically, this takes the form of inflation indexing, which is common in income tax law and which simply means that fixed dollar (or cent) values in the law will be regularly updated to account for changes in the price level in the economy. If prices rise by 2 percent, for example, then the gas tax rate will rise by 2 percent as well, thereby holding its real value steady over time. With gas taxes, these indexing formulas sometimes look to a broad measure of inflation throughout the economy and sometimes to a narrower measure that considers transportation construction cost inflation. Additional detail on the approach taken in each state is available in Figure 2.

Two states (Nebraska and New Jersey) levy tax rates connected either to a target revenue or spending level. The intent of these designs is to foster some degree of connection between gas tax revenues and expenditure needs, though these structures tend to be less effective than inflation indexing in accomplishing that goal.

The popularity of variable-rate gas taxes connected to cost growth is on the rise. As recently as 2012, just two states (Florida and Nebraska) levied their gas taxes in ways that allowed the rate to adjust alongside some measure of spending need. Today, that count stands at 18 states plus D.C.

Variable-Rate Taxes and Fuel Efficiency

The distinction for best gas tax design in the nation belongs to Georgia, which uses a two-pronged indexing formula that considers both inflation and rising vehicle fuel efficiency. Considering both improves sustainability because fuel efficiency gains cut into the number of gas tax dollars paid per mile driven and inflation reduces the purchasing power of each gas tax dollar collected. Georgia lawmakers, with this design, are helping the tax keep pace with both fuel efficiency gains and rising construction costs.

It bears noting, however, that even the Georgia design does not fully address the impact that advancing vehicle technology is having on gas tax revenue collections. Fully electric vehicles obviously will not pay gas taxes regardless of the gas tax design in place. While electric vehicles make up only a small share of the overall vehicle fleet today, some lawmakers view their non-payment of gas taxes as a problem and are increasingly setting higher vehicle registration fees for electric vehicles and considering new taxes levied on the number of miles traveled to ensure that owners of these vehicles contribute to funding the transportation network. These ideas are worthy of consideration but, given the seriousness of the climate crisis, any adjustment in policy should be done carefully to avoid discouraging the adoption of highly efficient cars. Maintaining a robust gas tax for the long run can be one part of a strategy for accomplishing that goal.