Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

Map of State Treatment of Itemized Deductions

Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia allow a group of income tax breaks known as “itemized deductions.” [1] Itemized deductions are designed to help defray a wide variety of personal expenditures that affect a taxpayer’s ability to pay taxes, including charitable contributions, extraordinary medical expenses, mortgage interest payments, and state and local taxes. But these deductions reduce state revenue by billions of dollars each year while providing the greatest benefit to upper-income households—and little to no benefit to the middle- and low-income families that generally pay the highest share of their incomes in state and local taxes. [2] This policy brief explains itemized deductions and explores options for reforming these regressive tax breaks at the state level, including recent reforms that have been enacted in a number of states.

What are Itemized Deductions?

When calculating the amount of one’s income that is subject to tax, the federal government and most states allow people to choose whether to subtract a basic “standard deduction” amount or the total of their “itemized deductions”—a group of roughly a dozen separate tax deductions. Most states with personal income taxes “couple” to the federal government’s itemized deduction rules, allowing people who utilize itemized deductions on their federal tax returns to do so at the state level as well. Generally, better-off families are more likely than lower-income families to have enough deductions to make itemizing worthwhile. Deductions related to homeownership are often what makes a family’s itemized deductions exceed its standard deduction.

In general, the rationale for each itemized deduction is to take account of large or unusual personal expenditures that affect a taxpayer’s ability to pay. Some itemized deductions are also offered as a way of encouraging certain types of behavior. The largest itemized deductions include those for charitable contributions, mortgage interest paid by homeowners, large medical expenses, and state and local income, property, and sales taxes. Since it makes little sense to deduct a state income tax payment from a state income tax payment, most states require itemizers to add back any state income tax deduction claimed on federal tax forms when recalculating their itemized deductions for state purposes.

Fairness Implications of Itemized Deductions

Itemized deductions impact tax fairness: low-income families receive virtually no benefit from these deductions, and the largest benefits are reserved for the upper-income families who arguably need them the least.

There are multiple reasons for this outcome. Many low-income families do not own their homes, for instance, and thus do not benefit from the deductions for mortgage interest or property taxes paid. Those families are also unable to give significant amounts to charity, and they do not tend to make large, deductible state income tax payments.

The regressive nature of itemized deductions is amplified by the fact that under an income tax with graduated rates (where the marginal tax rate rises as income rises), any type of tax deduction will tend to provide a larger benefit to the best-off families. This is because the tax cut offered by an itemized deduction depends on the taxpayer’s income tax rate. Imagine two families, each of which paid $10,000 in mortgage interest that they include in their itemized deductions. If the first family is a middle-income family paying at the 15 percent federal tax rate, the most they can expect is a $1,500 federal tax cut from this deduction ($10,000 times 15 percent). But if the second family is much wealthier and pays at the 39.6 percent top rate, they could expect a tax cut of up to $3,960. Since the vast majority of states allowing itemized deductions also use a system of graduated tax rates, this upside-down effect is common at the state level as well.

State Treatment of Itemized Deductions

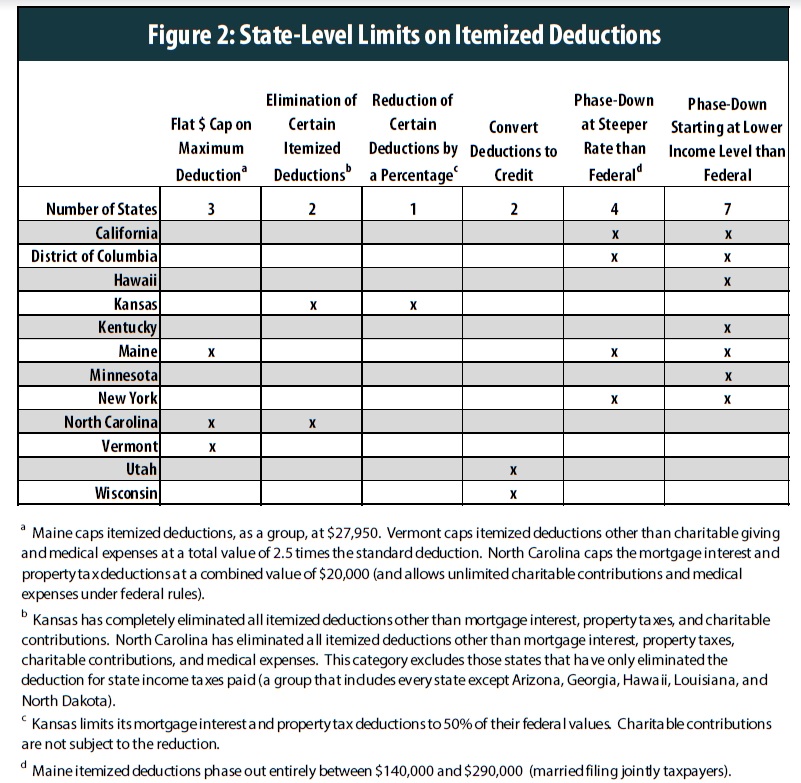

Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia (DC) allow itemized deductions patterned after federal rules (Figure 1). Seventeen states closely follow federal guidelines for itemized deductions (with the exception of the federal deduction for state income taxes paid, which most states have sensibly chosen to disallow). Eleven other states and DC use the same federal guidelines, but impose their own limits on some or all of these deductions (See Figure 2 for more detail on these states). Just three states (Alabama, Arkansas, and South Carolina) offer itemized deductions without any kind of limit or phase-down. By contrast, ten states with broad-based income taxes do not allow any of these itemized deductions, opting instead to establish their own rules for determining taxable income that may include deductions for various expenses but are not based on the federal deduction structure and do not restrict those deductions to itemizers.

Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia (DC) allow itemized deductions patterned after federal rules (Figure 1). Seventeen states closely follow federal guidelines for itemized deductions (with the exception of the federal deduction for state income taxes paid, which most states have sensibly chosen to disallow). Eleven other states and DC use the same federal guidelines, but impose their own limits on some or all of these deductions (See Figure 2 for more detail on these states). Just three states (Alabama, Arkansas, and South Carolina) offer itemized deductions without any kind of limit or phase-down. By contrast, ten states with broad-based income taxes do not allow any of these itemized deductions, opting instead to establish their own rules for determining taxable income that may include deductions for various expenses but are not based on the federal deduction structure and do not restrict those deductions to itemizers.

Options for Itemized Deduction Reform

In recent years, lawmakers in a number of states have ratified bold reforms that phase down or even repeal itemized deductions. The outright repeal of itemized deductions in Rhode Island in 2010 was the most significant of those efforts thus far. Other states have capped the value of some deductions or converted them into credits—making these tax breaks less unfair and broadening the state’s income tax base (Figure 2). Most recently, Kansas, Maine, North Carolina, and Vermont enacted changes to reduce the value of itemized deductions for their best-off taxpayers. Options for itemized deduction reform include:

• Repealing Itemized Deductions Entirely: The most comprehensive reform approach available to states is to simply repeal all itemized deductions. Middle- and low-income families can be held harmless under such a change by simultaneously increasing the basic standard deduction available to all families. This was the approach taken in Rhode Island in 2010.

• Capping the Total Value of Itemized Deductions: Itemized deductions typically have no caps—so well-off taxpayers with valuable homes, for example, are able to use the property tax deduction to an extent that is unavailable to lower- and middle-income taxpayers. States can pare back deductions for the best-off taxpayers by limiting the total amount of itemized deductions that can be claimed. Maine, North Carolina, and Vermont have implemented caps in the past few years.

• Allowing only Certain Itemized Deductions and/or Reducing Deductions by a Percentage: Another option for limiting itemized deductions is to allow only a few specific deductions rather than the full list available on federal tax forms. Kansas and North Carolina have recently reduced the number of available itemized deductions to just three or four of the major federal deductions. Deductions for charitable contributions and medical expenses are most frequently singled out as tax breaks that even reform-minded states tend to keep on the books (or to exempt from the caps mentioned above). Kansas also allows only half of the federal value for two of the deductions it does allow.

• Converting Itemized Deductions to Credits: One important contributor to the “upside-down” nature of itemized deductions is that they give larger benefits to the upper-income taxpayers who face higher marginal tax rates. Converting these deductions into a credit is one way to ensure that the tax impact of itemized deductions depends more directly on the amount of deductions a taxpayer claims—not on their marginal income tax rate. Reforms enacted in Utah and Wisconsin offer examples of this approach.

• Enacting Stand-Alone Phase-Down Provisions: At the federal level, a provision known as the “Pease” disallowance (after its author, Rep. Donald Pease) reduces some itemized deductions for upper-income taxpayers. Most states adhere, or “couple,” to this provision as well. The Pease disallowance is effective at reducing the regressivity of itemized deductions, though coupling to federal law in this way leaves states vulnerable to continually evolving federal rules, including the gradual repeal of Pease from 2006 to 2010, extension of that repeal for 2011 and 2012, and its reinstatement with higher income limits beginning in 2013. States can choose to set their own income limits and phase-down rules to ensure a predictable, and potentially more progressive, method of limiting itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers. Six states and DC have taken this approach, including California, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, and New York. Maine is the only state that fully phases out itemized deductions for upper-income taxpayers (and also caps them for others).

Itemized Deductions and Broader Tax Reform

Some lawmakers may find it tempting to pair itemized deduction reforms with income tax rate cuts in an effort to achieve a broader tax base with lower tax rates. But if such rate cuts are excessively large or skewed in favor of the wealthy, other important tax policy principles—such as promoting tax fairness and maintaining adequate revenue streams to fund vital public services—can be compromised in the process. States considering itemized deduction reform must balance these factors carefully. Every state’s tax structure currently leans more heavily on low-income families than on those with higher incomes, and many states are struggling with recurring revenue shortfalls and underfunded services. Given these realities, pairing itemized deduction reform with tax reductions targeted to low-income families, or using the revenue to strengthen state investments in schools, roads, and public safety is a more desirable approach in many states.

Conclusion

Itemized deductions are costly, “upside-down” subsidies for the best-off taxpayers that offer little or no benefit for many low- and middle-income families. Reforming these deductions can make tax systems more equitable and sustainable at a time when they are badly in need of such changes.

Itemized deduction reform continues to gain traction. A 2010 bipartisan national fiscal commission recommended reducing or eliminating specific federal itemized deductions as an important step toward improving the federal tax code. [3] Recent state tax commissions in Delaware and Louisiana made similar recommendations and more states are exploring these options. Rhode Island’s landmark elimination of itemized deductions in 2010 and Maine’s thoughtful 2015 overhaul are just two leading examples of states taking action in this important area.

[1] As of Tax Year 2016.

[2] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All Fifty States. 5th Edition. January 14, 2015. Available at: www.whopays.org.

[3] National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The Moment of Truth. December, 2010. Available at: https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/ObamaFiscal/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf