It’s rare to see a tax policy idea sweep through state legislatures across the nation as quickly as the gas tax holidays being discussed right now. Until a few months ago, the need for higher and better-designed gas taxes was among the few issues that state lawmakers from both parties could agree on. Now, the opposite is true. Nearly half the states (and the federal government) are considering backing off the gas tax by temporarily repealing or reducing it, or by preventing a scheduled increase from taking place. Lawmakers’ impulse to lessen the blow of higher prices on consumers is admirable and, frankly, a gas tax holiday is nowhere close to being the worst state tax proposal to surface this year. But it’s unlikely that state gas tax holidays will meaningfully benefit consumers, and they come with risks for states’ infrastructure quality.

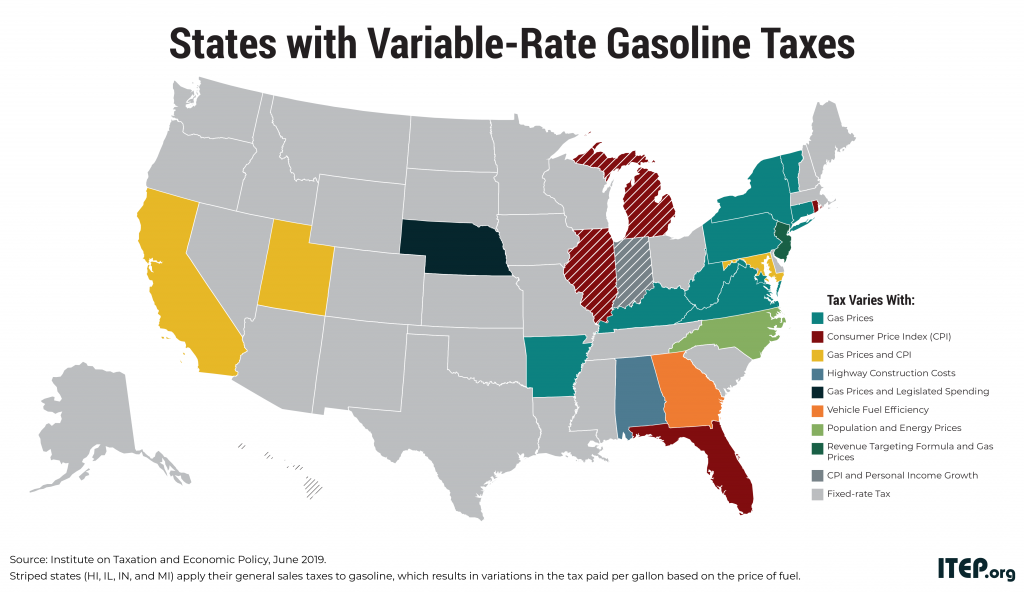

The nation’s transportation infrastructure is funded through a variety of revenue sources, with gas tax dollars making the single largest contribution. Lawmakers have placed the gas tax at the center of our infrastructure funding system based on the premise that drivers who make the heaviest use of our roads and bridges should pay more for their upkeep.

But while the gas tax is undoubtedly a tax on drivers, this does not mean that every incremental change in the tax rate finds its way to drivers in a timely manner. When Illinois and Indiana last tried temporary gas tax holidays, for example, about 30 percent of the tax savings were pocketed by the oil industry and there are reasons to think that share might be even higher in today’s supply-constrained environment. Given recent price volatility and the possibility that a sizeable share of a temporary tax cut won’t show up in the price being charged at the pump, it’s likely that many drivers will not notice a price cut during such a holiday.

Presumably, lawmakers’ primary aim in suspending the gas tax is to lower the expenses facing their middle-income and low-income constituents who are least able to afford them. But gas tax holidays are not an especially well-targeted way to reach this group. Even under relatively generous assumptions, I anticipate that less than half of the revenue sacrificed through this kind of holiday would find its way into the pockets of low- and middle-income residents, with the remainder flowing to some mix of oil companies, tourists, high-income families, and long-haul truckers just passing through. Of course, the top-heavy income tax cuts being discussed in states like Mississippi and Kentucky would steer an even smaller share of their tax cuts to ordinary families, so it’s also true that gas tax holidays aren’t the worst offenders by this measure.

For lawmakers interested in a somewhat more targeted approach, tax rebate proposals under consideration in states like California (limited to vehicle owners) and New Jersey (limited to people with incomes below a certain level) offer a more direct way of offsetting high prices without having to trust the oil industry to pass along its tax savings. New or expanded Earned Income Tax Credits (EITCs) or Child Tax Credits (CTCs) could play a similar role, and in fact could be even more carefully targeted to the families most in need. The challenges created by the rising cost of living can also be dealt with through deeper public investments in areas like affordable childcare, universal preschool, higher education, housing, and health—all areas that comprise a significant share of many households’ annual spending.

If gas tax holidays have one saving grace, it’s that they would likely be temporary and therefore wouldn’t constrain state revenue growth over the long haul. (A tax rebate, of course, could also be designed as a temporary policy.) But if gas prices remain high for an extended period, lawmakers could face intense pressure to renew these holidays even as they become increasingly unaffordable in the face of rising construction costs. The most recent data on highway construction costs already show a 10 percent increase from a year earlier, and that’s with a six-month lag in reporting that does not fully capture recent increases in the price of diesel, asphalt, and other materials that go into building and maintaining our transportation network.

Much of the discussion around state fiscal policy as of late has centered on how to use the tax code to blunt the financial impact of high inflation on consumers. But before long, lawmakers are going to need to look at inflation’s impact on the other side of the ledger and have a frank discussion about how rising prices throughout the economy also affect the cost of providing high-quality schools, infrastructure, and other services. As that reality begins to come into sharper focus, and as temporary infusions of funding from the federal government are spent down, the tax cut fervor driving interest in gas tax holidays and other ill-advised tax cuts will loosen its grip and the states that have been most aggressive in their tax cutting will undoubtedly be facing a much more difficult budget outlook.