This blog was co-authored by Steve Wamhoff and Joe Hughes

Inflation is hard on Americans, and there are several policies that might effectively address it. A proposal from a group of Senate Democrats to provide a “holiday” from the federal gas tax until the end of the year is not one of them.

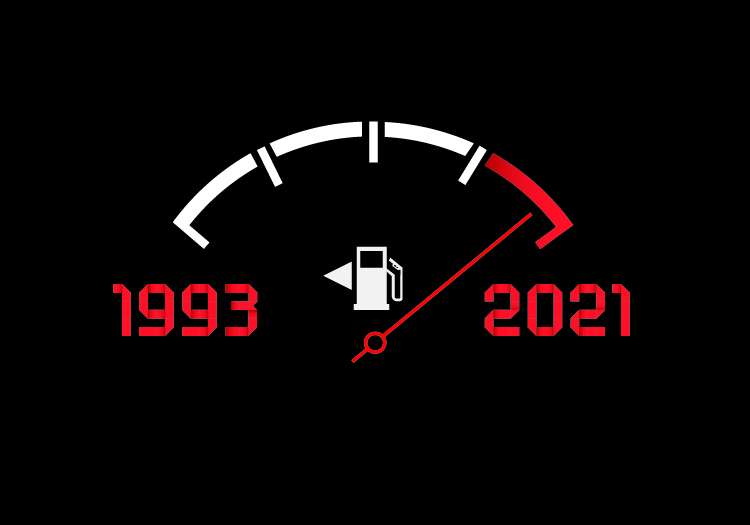

The concept of suspending the gas tax is not new. Back in April of 2008, presidential candidate Barack Obama criticized the idea when it was proposed by rival candidates John McCain and Hillary Clinton. At that time, inflation had already substantially eroded the real revenue impact of the tax. More than 14 years had passed since Congress had set it at 18.4 cents per gallon of gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of diesel back in October of 1993. Today, almost another 14 years have gone by, and Congress still has not raised the tax from its 1993 levels. The real revenue impact of the tax has fallen even more and the argument for suspending the tax is weaker than ever.

In the meantime, cars have become more fuel-efficient, which is a positive development for the environment and for consumers – and it also means that Americans pay less gas tax.

As our colleague Carl Davis explained a year ago, these two developments – lack of indexing for inflation and increased fuel efficiency – have reduced the purchasing power of the gas tax by 72 percent since its last adjustment in 1993.

This is a problem because federal gas tax revenue goes towards the Highway Trust Fund, the federal government’s main mechanism to finance transportation infrastructure. The cost of building this infrastructure continues to grow much more rapidly than the revenue collected from the federal gas tax, as illustrated in the graph below. These figures do not even account for more recent price increases, which are not reflected in the available data.

Suspending the gas tax might seem like an appealing idea to politicians because people notice how much they pay at the pump more readily than they notice the impacts of other policy changes. But it would not make much of a difference in people’s lives.

The national average gas price is up one dollar from a year ago, driven by global markets recovering from the pandemic and by geopolitical turmoil in Eurasia. Even if Americans trust companies like Exxon and BP to pass on the full savings of the gas tax holiday to consumers, the difference would only be 18.4 cents per gallon. The average driver would save less than $8 a month, according to the most recent statistics from the Federal Highway Administration. Gas prices are not going up because of onerous taxation, and they will not meaningfully go down because of a tax holiday.

The funny thing about “temporary” tax cuts is that once they are in place, even if they are totally unnoticed or trivial to most people, lawmakers find it difficult to allow them to end as scheduled. And if the federal gas tax holiday becomes permanent, then the cost in terms of transportation funding lost would seem far greater than the barely noticed benefits at the pump.

The bill introduced in the Senate to suspend the gas tax would cost $20 billion according to one estimate. (As a technical matter the bill would transfer general revenues into the Highway Trust Fund to replace the dollars lost.) A $20 billion price tax may not sound like much in the context the federal government’s budget, but the situation could become more problematic if lawmakers find this to be yet another “temporary” tax break they cannot tear themselves away from.

There are any number of more effective policies that might address the price increases that Americans are facing today. Policies that move us away from our dependence on fossil fuels and our vulnerability to the volatile oil markets are very important in the long-term both to protect us from such price increases and to combat climate change. Suspending the gas tax would work directly against those goals.

To address the rising costs of living more generally, policies like the increased Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) included in the Build Back Better Act would help some of the most vulnerable workers and families cover the costs of necessities without adding any noticeable inflationary pressures. As the economist Jason Furman recently explained, even under the most pessimistic assumptions, the increased CTC would cause prices to rise by $200 at most during a year for the typical family of four, which would be trivial compared to the thousands of dollars in additional CTC benefits they would receive under the bill. A gas tax break worth $8 a month is no replacement for these life-changing policies.