When you think of manufacturing, what comes to mind? According to the U.S. Congress, manufacturing may include things like the production of wrestling-rated films, assembling bouquets of flowers and even slicing cheesecake.

These unusual definitions of manufacturing come from the domestic production activities deduction (better known as the manufacturing deduction), a tax break Congress created to encourage manufacturing in the United States. The manufacturing deduction allows for a 9 percent deduction in profits from domestic production activities, which means that companies can significantly reduce their taxes with the deduction. While this may sound fine in theory, the reality is fraught with problems.

To start, once you give a lower tax rate to certain activities, every company has an incentive to define their activities as eligible for the tax break. In the case of the manufacturing deduction, companies have proven especially effective at stretching the definition of “domestic production activities” beyond recognition. In fact, the tax break can now be applied to one-third of all corporate activity. The most absurd example of this is the Cheesecake Factory restaurant group claiming the deduction for “producing” cheesecake because restaurant employees apply garnishes to and slice pre-baked cakes.

The lack of clarity in what constitutes domestic production has also added uncertainty to the tax laws, as companies and the IRS are forced to litigate whether different activities fall under the break.

The manufacturing tax break also provides a small reduction in tax rates (9 percent of 35 percent), so it’s hard to imagine that it could change companies’ decisions about where to locate their manufacturing facilities. Which means that in general, the manufacturing deduction gives companies a tax break for doing something they were going to do anyway.

It’s not surprising that economic analyses of the manufacturing deduction have found that there is virtually no evidence that the credit has resulted in additional domestic investment or job creation.

In part due to the failure to narrowly define it, the manufacturing deduction has grown into one of the largest corporate tax breaks in the code. Its annual cost has grown five-fold since 2005, rising from $3 billion in 2005 to $15 billion in 2016. In 2016, the top 25 recipients of the credit saved $2.9 billion in taxes, thus claiming almost one-fifth of the credit.

The manufacturing deduction is costly, complex and ineffective, and Congress should rescind it. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), eliminating the deduction could raise $174 billion over 10 years. This revenue should be used to either lower the deficit or to make much-needed public investments in infrastructure and other projects that have a proven track record of making the U.S. economy stronger.

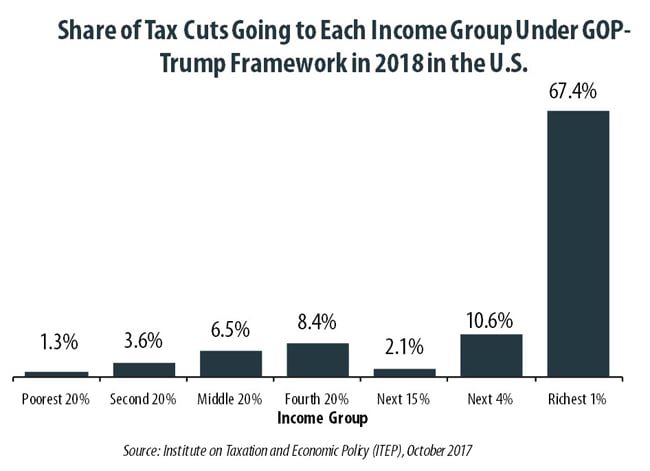

The Trump-GOP tax framework appropriately calls for the repeal of the manufacturing deduction, but it proposes to use the revenue raised to help offset a deep cut in the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent and an expansion of other tax breaks in the code. Congress should eliminate the misused manufacturing tax break. But it should not replace it with a huge overall corporate tax cut that would deprive the federal government of $172.7 billion a year in needed revenue.