Republicans in Congress argue that federal spending has grown so out of control and created such a severe budget deficit that we should default on the national debt accumulated under previous Congresses of both parties if the President doesn’t agree to substantial spending cuts. They know full well that such a debt default would spark an economic cataclysm, but the premise underlying their argument – that overspending by the federal government has caused the budget deficit – is wrong, according to a new report from the Center for American Progress. The real problem is that tax cuts have drained trillions of dollars from federal coffers – tax cuts that have mostly enriched the wealthiest Americans.

The report points out that as recently as 2012, the Congressional Budget Office projected the federal government would indefinitely collect more than enough revenue to cover federal spending outside of interest payments on the debt, meaning the debt would fall over time. But the situation changed that year when Congressional Republicans pushed to extend the Bush tax cuts past their expiration date at the end of 2012 and then-President Obama compromised and made some, but not all, of the tax cuts permanent. The fiscal outlook further deteriorated with the enactment of the Trump tax cuts in 2017.

So, while it is true that federal spending has grown (primarily because demographic changes mean more people qualify for Social Security and Medicare), revenues would have covered this spending if not for the tax cuts that have been enacted in the past 20 years. But rather than reversing any of those tax cuts, Congressional Republicans have proposed to make permanent the temporary portions of the Trump tax cuts, which would add more than $300 billion every year to the deficit. According to a recent report from the Congressional Budget Office, their approach to decreasing the deficit—program cuts for the middle class paired with tax cuts for the rich—is more unserious than it seems. It is mathematically impossible.

A Brief History of Time (and Budget Shortfalls)

When lawmakers insist that the current government funding gap is a function of runaway spending, they are putting blinders on to half of the federal budget. Budgets are always two-way streets. If the money coming in is less than the money going out, then a thorough audit should look at both revenues and expenses.

This is the approach taken by Bobby Kogan at the Center for American Progress in a report that examines long-term budget projections since the end of World War II. Contrary to the assertions of many budget hawks, Kogan finds that recent budget shortfalls are principally a result of tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations.

Kogan explains that the path to long-term budget stability involves a few factors. First, there is the “primary” deficit or surplus, which refers to the budget minus interest payments on existing debt. The second factor is the ratio of economic growth to the government’s interest rate. If the government runs a primary surplus (that is, revenues exceed outlays), then economic growth needs only to match the Treasury interest rate for the federal debt ratio to fall.

It’s fairly simple math, but somehow, starting in the 1980s, lawmakers got their arithmetic all wrong. Charlatans like Art Laffer, masquerading as serious economists, convinced politicians that cutting tax rates would magically raise revenues and lower the debt because economic growth would be so strong. The argument was not entirely sensible and was proven wrong when the Reagan Administration enacted tax cuts and severe budget deficits resulted.

Lawmakers from both parties realized the follies of the supply-side fraudsters and passed tax increases to reverse their mistakes. By the end of the Clinton Administration, the federal government ran a primary budget surplus that was projected to extend into perpetuity. Government expenses were expected to rise through the next few decades as the Baby Boomer generation aged and started drawing from Social Security and Medicare, but tax revenues were expected to rise even faster as income grew and the next generations entered their prime earning years.

Inexplicably, Congress made the same arithmetic mistakes from the 1980s all over again. First, the Bush administration slashed tax rates—a move that was dressed as a tax cut for everyone but overwhelmingly went to the rich. President Obama refused to make all of the Bush tax cuts permanent as Republicans who controlled the House of Representatives at the time demanded, but he did agree in 2012 to make most of them permanent. And most recently, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act enacted under former President Trump added significantly to the shortfall.

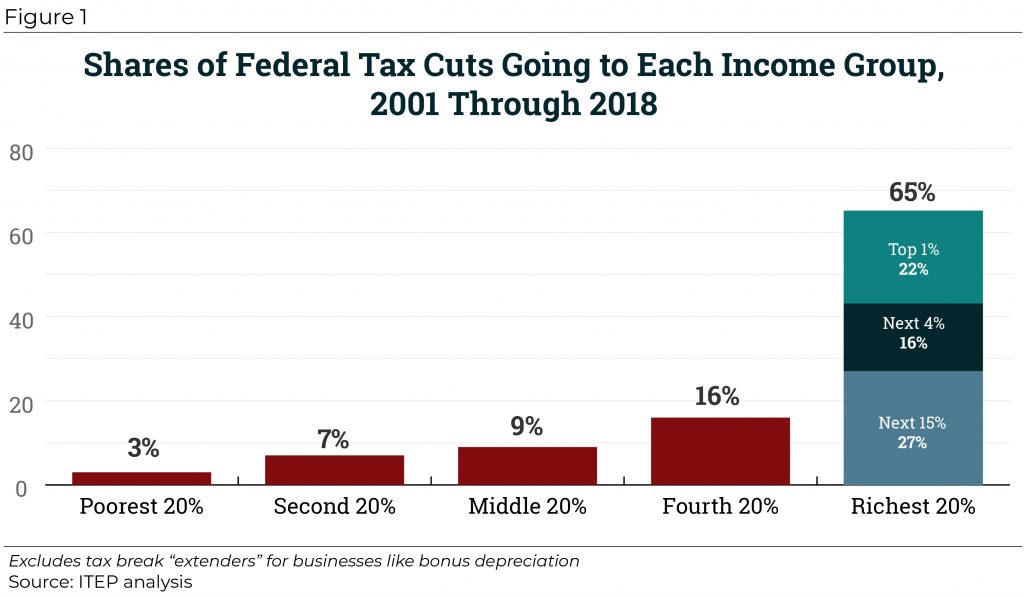

These tax cuts have cost more than $10 trillion in the first quarter of this century, according to the report. ITEP previously found that, as of 2018, nearly two-thirds of tax cuts passed since 2000 had gone to the richest fifth of Americans and a little under half had gone to the richest five percent of Americans. And that is not counting the significant portion of Trump’s corporate tax cuts that ultimately flowed to foreign investors.

And if Congress extends the parts of the Trump tax law set to expire at the end of 2025, this shortfall will balloon by trillions more.

The same lawmakers who worked to ensure this tax legislation benefited their wealthiest supporters are, in many cases, now claiming the only fiscally responsible approach is to cut programs that the middle class depends on. For example, ProPublica reported how Sen. Ron Johnson demanded that the Trump tax law include a provision that would benefit the uber wealthy owners of the packaging company Uline, who are major supporters of his campaigns. Recently, Sen. Johnson argued that a solution to our fiscal problems is to eliminate Social Security and Medicare as entitlement programs, meaning they would expire every year unless Congress appropriated funds for them annually.

Of course, spending is not irrelevant to budget deficits either. The stimulus spending that counteracted the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic added more to the shortfall. But these were one-time emergency expenses. They represent the exact type of situations where most economists agree that governments should outspend revenues. If this emergency expending is excluded, then the Bush (and Obama) and Trump tax cuts are responsible for 90 percent of the increase in the debt ratio – growing to more than 100 percent over time.

This means that, if not for these expensive and regressive tax cuts, debt as a percent of the economy would be declining indefinitely despite the growth in spending. Put this way, the federal debt doesn’t sound very much like a runaway spending problem at all. It starts to look much more like a runaway tax cut problem.

Making Up Lost Ground

Even without this historical data, as a matter of arithmetic, any path toward lower budget deficits would involve tax increases and not just cuts to government programs. The director of the Congressional Budget Office—Congress’ official, nonpartisan budget scorekeepers—said as much in a publication released earlier this year.

He looked at what it would take for Congress to reduce the primary deficit to its historical size over the last 50 years and found that lawmakers would need to come up with $5 trillion in either program cuts or revenue increases to close the gap. He then outlined the largest options for reducing the deficit. If lawmakers remain committed to pledges not to cut Social Security or Medicare, then there are only two viable paths: slash programs that help the middle and working class, or raise taxes.

Out of the 13 options that would not cut Social Security or Medicare, seven would raise taxes. Even if Congress adopted all of the most severe spending cuts presented—capping Medicaid spending, slashing anti-poverty programs, reducing military personnel by 20 percent, putting new limits on veterans’ disability payments, and cutting highway and education spending—it would not get lawmakers back to historical deficit levels without additional tax increases.

The math simply isn’t there for lawmakers who want to reverse the federal debt trajectory without raising taxes. Counter to their narrative that runaway spending is to blame, it’s clear that low taxes for the wealthy have been the problem all along. Lawmakers have repeatedly stepped on the same rake of slashing tax rates and expecting revenues to magically go up. Now they want middle-class Americans to be the ones who get hit in the face. The con is getting tired. If Congress wants to reel in the debt then it’s time to raise taxes on the wealthy.