The Trump Administration is considering cutting the Social Security payroll tax to boost the economy, something that seemed more justified when enacted in the aftermath of the Great Recession—when congressional Republicans largely opposed it. Here are some things to remember about this tax.

First, cutting the payroll tax threatens Social Security, at least indirectly.

The payroll tax in question funds Social Security, a source of economic security for millions of workers and their families, and it should not be cut except in extreme situations.

In 2011 and 2012, Congress and President Obama reduced the part of the tax paid directly by employees from 6.2 percent to 4.2 percent. Social Security was, in theory, not harmed because Congress replaced the funds with general revenue (the revenue the government collects from other taxes).

But if Congress and successive presidents routinely cut the Social Security payroll tax, this will inevitably raise questions about whether general revenues are sufficient to offset the enormous loss of funds for Social Security and whether the program itself must be cut to make up the difference.

Second, the last Social Security payroll tax cuts were enacted during cataclysmic economic conditions inherited by President Obama, and many congressional Republicans opposed them.

The Obama Administration argued that, unlike other tax cuts, a payroll tax cut would put money in the hands of more low- and middle-income people who tend to spend any new money they receive, pumping it back into the economy, sending customers to stores and other businesses that can, in turn, hire more workers or at least avoid layoffs. But congressional Republicans claimed it would not help the economy, and the House GOP initially blocked the extension of the payroll tax cut into 2012 even after the Senate approved it.

If the mere suggestion that a recession might threaten their own election prospects is enough to send Republicans rushing to embrace an economic stimulus tool they opposed during the Obama years, that would be blatantly hypocritical and nakedly political.

Third, it’s not accurate to call a payroll tax cut a “middle-class” tax cut.

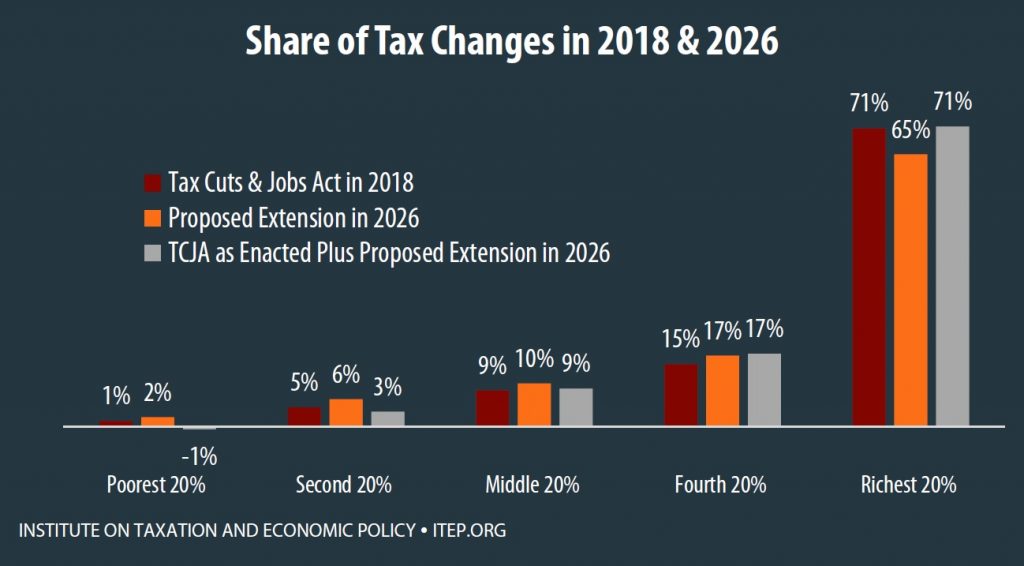

It is true that a payroll tax cut is more targeted to the middle-class than, say, the Trump-GOP tax cuts. But being better for the middle-class than the 2017 tax law is hardly a high fence to scale. More than 45 percent of the benefits of the 2011-2012 payroll tax cuts went to the richest fifth of households during both years. That’s less than the 71 percent of the benefits from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) going to the top fifth in 2018, but that hardly seems like the right standard to judge the fairness of a tax proposal.

The Social Security payroll tax is paid on earnings, not on any of the investment income that mostly goes to the rich. And earnings above a certain level ($132,900 in 2019) are exempt. So, the tax has less of an effect on the rich, and cutting the tax helps the rich less than other types of tax cuts. But it still disproportionately helps the well-off, who in most cases have at least $132,900 of earnings.

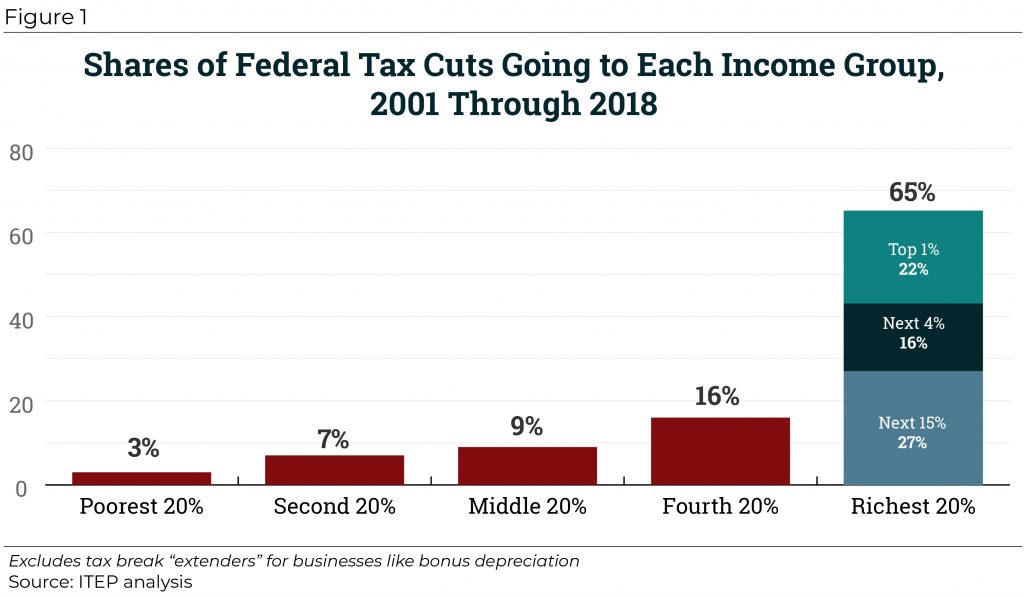

ITEP studied the payroll tax cut last summer as part of its report on all major federal tax changes enacted after 2000. The payroll tax cuts (which appear in the middle of the second table in Appendix I) cost an estimated $108.8 billion in 2011 and $113.2 billion in 2012. The portion that went to the richest 20 percent of households was 47 percent in 2011 and 46 percent in 2012.

Fourth, the Trump Administration’s consideration of this tax cut seems like an admission that its 2017 law did not benefit the middle-class after all.

Recall that the Trump Administration claimed that its 2017 tax law would primarily benefit the middle-class. For example, administration officials claimed that the law’s corporate tax cuts would trickle down to workers. ITEP, using the same methodology as Congress’s official revenue-estimators, concluded that most of the corporate tax cuts would go to the owners of corporate stocks and other business assets, and a huge portion would even go to foreign investors in American corporations rather than households here in the United States. Most of the other provisions in the law were not much better.

But if the White House is pursuing a payroll tax cut as a way to boost middle-class households who make up the consumers driving our economy, this would appear to be an admission of what we already know: The Trump-GOP tax cuts did little, if anything, for anyone who is not rich.