Key Findings

- The 2025 federal tax law risks making Section 529 college savings accounts more costly for states by expanding their use as vehicles for subsidizing private and religious K-12 schools, and by increasing the opportunities for tax avoidance by wealthy families. These changes expand on a controversial federal law enacted in 2017 that first opened the door to using these accounts to pay for K-12 tuition expenses.

- However, states are not required to provide state tax breaks on top of federal tax breaks for private school tuition. By decoupling from this aspect of federal tax law, states can forgo an inefficient subsidy for private schools and can help steer the use of 529 savings accounts back toward their original purpose.

Summary

A tax subsidy that 31 states and the District of Columbia offer to mostly wealthy private-school parents will soon grow even costlier to states – further reducing revenues available to fund public schools, health care, and other public services – unless they act quickly to undo it.

The culprit is a provision of the Trump tax law enacted in July 2025 that exacerbates an ongoing effort to quietly move public dollars into private schools through the unlikely mechanism of Section 529 education savings plans.

The original intent of 529 plans was to give a tax break to parents who save for their children’s college education. However, the 2017 Trump tax law subverted the original purpose as a long-term, tax-advantaged savings vehicle for higher education. Under a provision of that bill that squeaked through the U.S. Senate by the narrowest of margins, 529 funds can now be used for tuition at private K-12 schools, most of which are religious in nature.

The 2025 Trump tax law goes even further by boosting annual tuition withdrawal limits from $10,000 to $20,000 per beneficiary and expanding the definition of qualifying expenses to include unlimited spending on K-12 non-tuition costs, such as curriculum materials, books, and tutoring. Home schooling expenses also qualify now.

Of the 31 states plus D.C. that provide state tax subsidies to families that use 529 accounts to pay for K-12 private schooling, all but three go a step further than the federal government in the imprudence of those subsidies. These states not only allow money in 529 accounts to grow tax-free and to be used for K-12 tuition, but they also give parents a separate tax break for their initial contributions to these accounts. This means a private-school parent can get a tax break for merely putting money into an account and then withdrawing it immediately to pay for tuition.

Most of the benefits of this arrangement go to the wealthiest parents, because they are the most likely to have children in private schools, their schools charge the highest tuition, they are in the highest tax brackets, and they are more likely to have the resources and financial savvy needed to participate in 529 accounts.

Even when used for higher education, 529 plans are widely recognized as inequitable and relatively ineffective. Most of the benefits go to well-off families who would have been able to save for college anyway. A 2012 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that fewer than 3 percent of families participated in a 529 plan, and most benefits went to the wealthiest Americans.

But these tax subsidies are not inevitable. Ten states subsidize only higher education expenses, not K-12, for example by recapturing tax breaks for contributions and in some cases penalizing people who use the accounts in ways that are inconsistent with the original intent of saving for higher education. Other states can follow suit to avoid losing even more revenue to a top-heavy tax break that shifts money from public to private education.

State Tax Breaks for 529 Plans

States began creating higher education savings plans in the 1980s, and the federal government later passed legislation exempting 529 earnings from federal income tax.

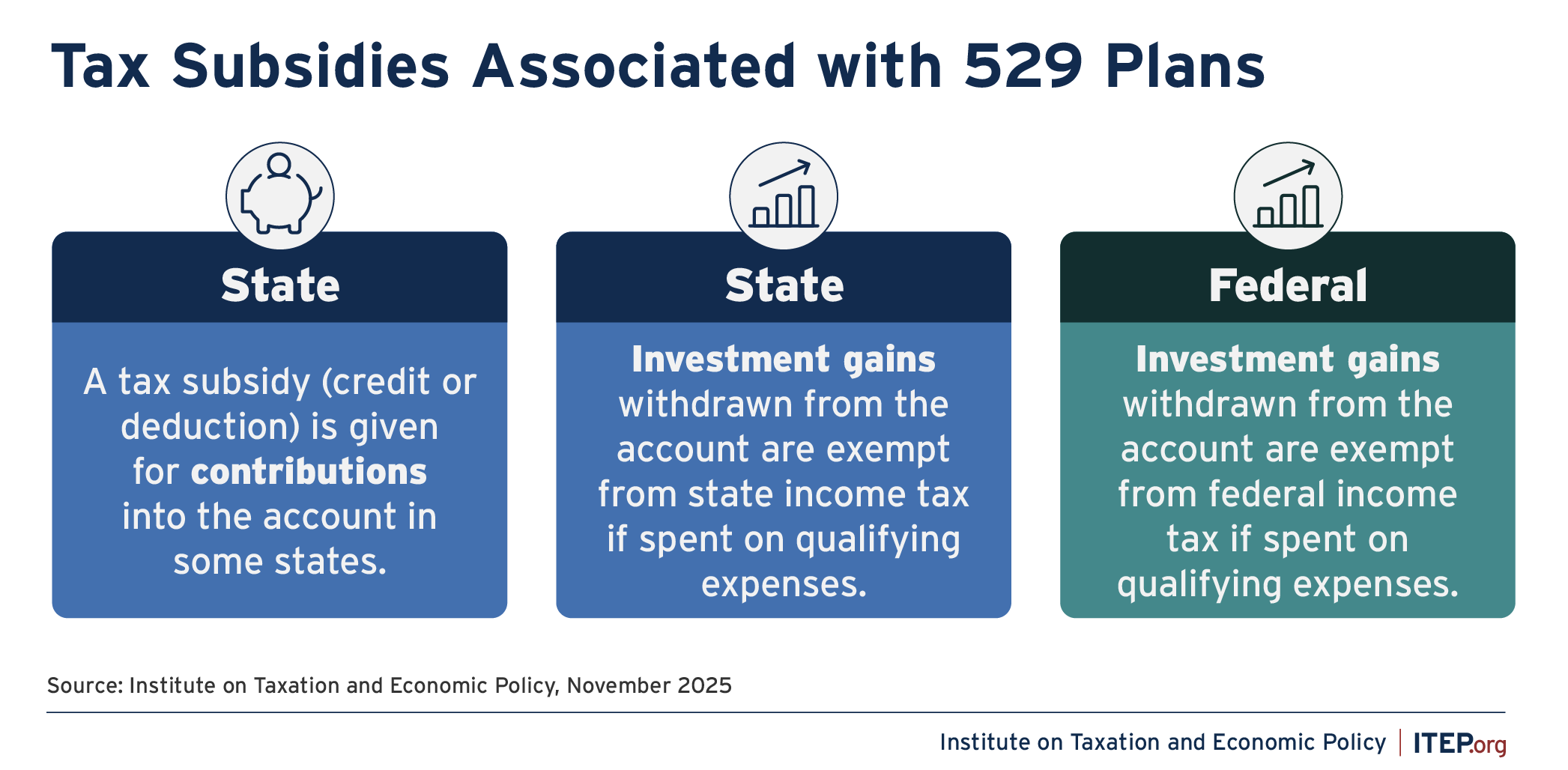

The plans are savings vehicles operated by states or educational institutions. Taxpayers can receive up to three different types of tax breaks when making use of a 529 plan, though not all these breaks are available in every state.

Figure 1

Every state that levies a personal income tax exempts qualified distributions from 529 plans.

Of those, 34 states and D.C. go a step further. Not only do they exempt the investment gains on money in 529 plans from state tax, but they also offer income tax credits or deductions for contributions to these plans. Of the states which offer these tax breaks:

- Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia offer deductions for contributions.

- Three states (Indiana, Utah, and Vermont) offer nonrefundable credits for contributions.

The other seven states with personal income taxes exempt qualified distributions but offer no tax benefit for contributions; they are California, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Minnesota, New Jersey, and North Carolina.

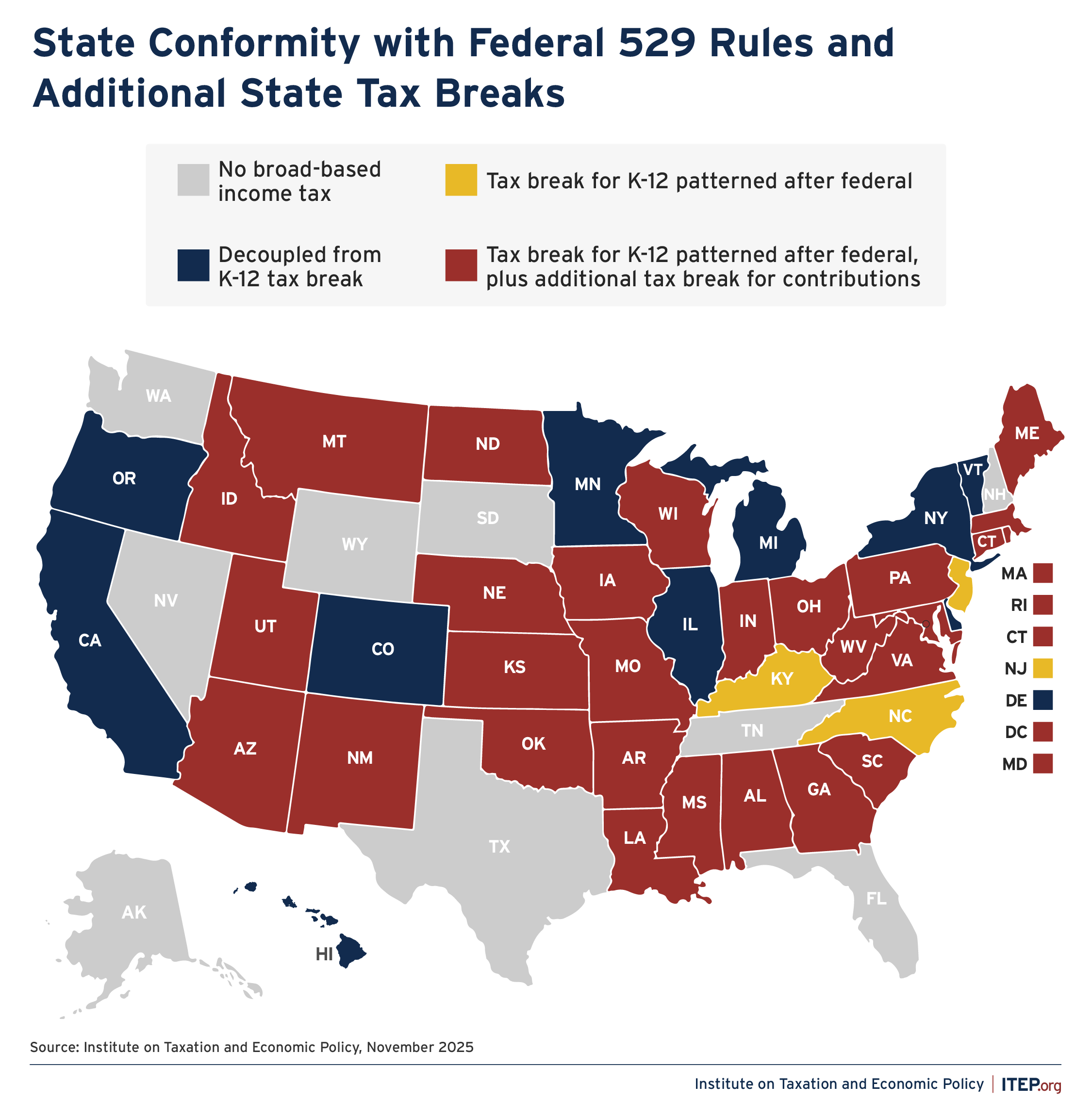

Figure 2

Equity Implications of Federal and State Expansion of 529 Plans to K-12 Education

Federal changes enacted in 2017 and 2025 have resulted in a strange circumstance where “qualified higher education expenses,” as defined in Section 529 of federal law, now include K-12 tuition and education spending for elementary and secondary students, such as for books, software, and tutoring. In other words, 529 plans – once specifically intended for college savings – are now available to fund private K-12 school expenses with the only limit being a $20,000 cap per student annually, doubled from $10,000 before 2025. There is no statutory limit on non-tuition expenses.

Expanding 529 accounts to become vehicles for covering K-12 private school tuition has made the tax subsidies offered by these plans less effective and less fair. Due to the structure of state tax breaks for 529 contributions, the primary outcome of this expansion has been to create new opportunities for tax avoidance.

Here’s why. Families, especially those who are not wealthy, typically do not save ahead for private K-12 school. Rather, they pay tuition semester by semester or month by month from their regular incomes. In states that offer deductions or credits for contributions, parents can make a contribution to a 529 account, receive the deduction or credit in exchange for their contribution, and then immediately withdraw those funds to pay for the private school expenses – minus whatever fees are charged by the private investment firms who manage 529 accounts. In this scenario, the 529 plan is not a savings vehicle at all, but rather a brief pit stop whose only purpose is to allow taxpayers to pay for their children’s private school education with pre-tax dollars.

Even conservative supporters of private schools have called the changes to 529 policy ineffective. Nat Malkus from the American Enterprise Institute criticized this transformation of 529 plans, saying that “the parents who will benefit most from these changes are those who already send their children to private schools or have access to tax advisors to help them plan their savings.” He has also noted that it erodes state tax bases that fund public schools, which hurts high-poverty schools the most. Private schools are not exclusively for the wealthy, but most K-12 tuition is paid by high-income households, and so well-off families are getting the bulk of the benefit from these tax subsidies.

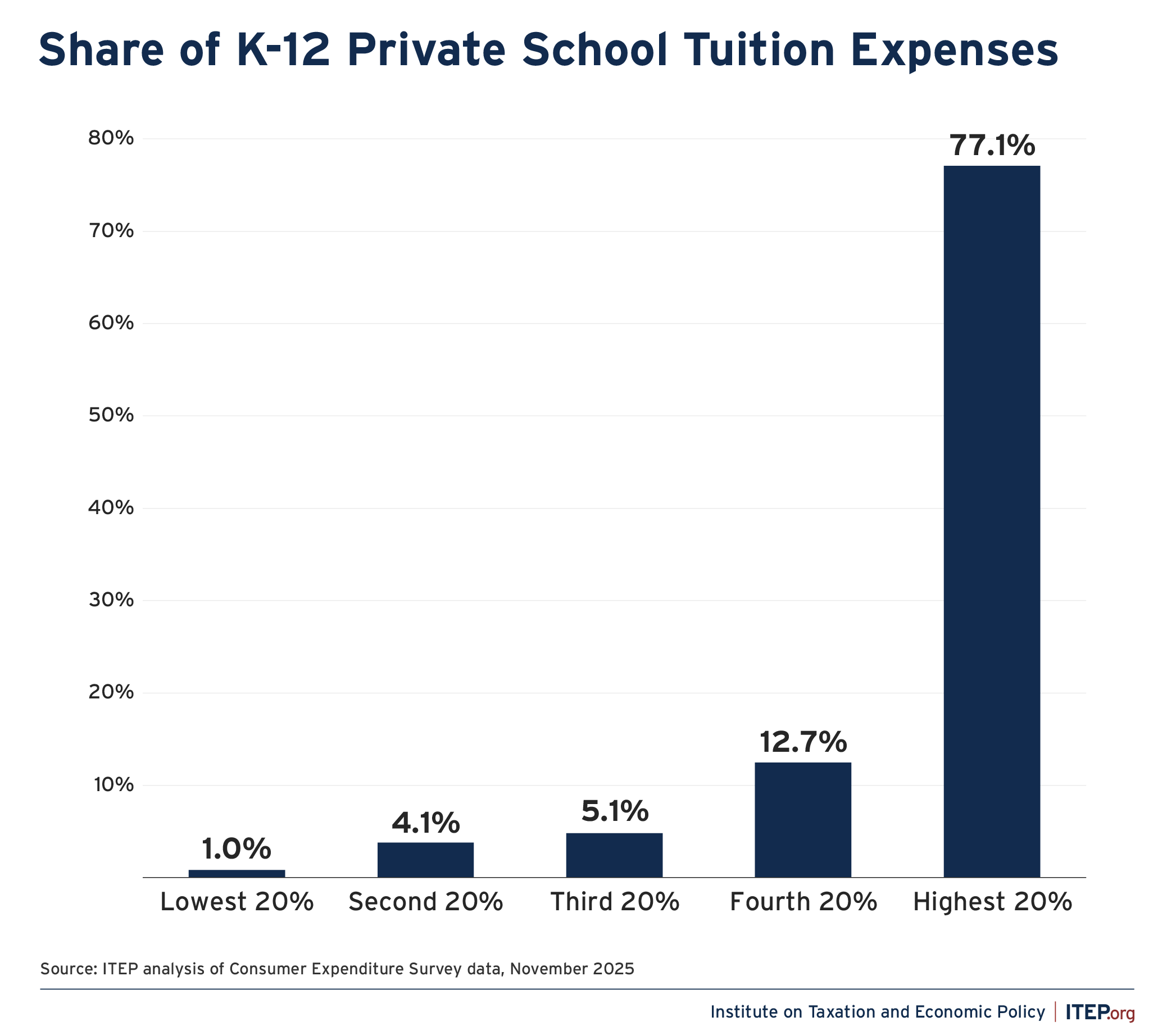

According to an ITEP analysis of data from the American Community Survey and the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the share of households sending at least one child to a private K-12 school is nearly twice as high among the top 20 percent, by income, compared to those in the bottom 20 percent. About one in five households in the high-income category send at least one child to private school, compared with one in ten for middle and lower-income households. And wealthy parents tend to send their children to much more expensive private schools. The highest-income 20 percent of households in 2023 accounted for 77 percent of all K-12 tuition expenditures; the bottom 60 percent of households accounted for just 10 percent of K-12 tuition spending. The increase in allowable 529 K-12 tuition expenditures from $10,000 to $20,000 per year under the new tax law will further concentrate the tax benefits among the wealthy.

Figure 3

The District of Columbia’s revenue office estimates that in 2027 contribution deductions and exemptions for investment returns will cost $4 million and $6.6 million, respectively, with 64 percent of the benefits being claimed by households with incomes over $200,000 with 64 percent of the benefits being claimed by households with incomes over $200,000.

In short, most families don’t send their kids to private schools, so they get no benefit from the K-12 tuition exemption. Instead, private-school parents reap the state tax benefits simply by cycling their tuition payments through 529 accounts, a tax dodge that mostly benefits a wealthy few. Black and Hispanic families are particularly unlikely to benefit from the Section 529 tax breaks for K-12 private school tuition, because even compared with white households of similar income levels they are less likely to send their children to private school.

Extending the federal law to private K-12 education and non-tuition expenses has had numerous, unproductive consequences for states. As outlined in Figure 2, of the 41 states plus the District of Columbia with personal income taxes, 31 states plus D.C. allow earnings from 529 plans to be used for K-12 schooling – and all but three of them go further than the federal government by not only allowing money in the accounts to grow tax-free, but also allowing an additional deduction or credit for contributions to the plans. Even before the 2025 changes expanding eligible K-12 expenses, tax breaks for 529 plans on the state level were depriving states of tens of millions of dollars that otherwise could have been used to support public schools.

While data are limited on the revenue impact of expanding deductions for K-12 contributions, fiscal notes in Nebraska and Ohio provide some useful evidence. In Nebraska, expanding the allowable uses of 529 accounts to include K-12 tuition was estimated to increase the cost of those deductions by more than 60 percent, from $5.5 million to $9 million a year. In Ohio, expanding the state deduction for contributions to K-12 was estimated to cost the state $20 million in 2019.

Decoupling from Federal Tax Law

States that want to retain their tax subsidies for college savings but avoid subsidizing private and religious K-12 tuition through these programs can follow the lead of the 10 states that have already done so. These states generally adopt a three-step approach.

- Tightly define expenditures: States establish in law or regulation that for purposes of state taxation, K-12 expenses from a 529 plan are non-qualifying expenditures. That means that if a taxpayer uses money in a 529 plan for K-12 spending, any profit that has been accrued while the money was in the 529 plan is subject to tax, as it would be if it were used for any other nonqualifying expenditure.

- Require repayment: States require repayment of the benefit from any state tax credits or deductions claimed for contributions to a 529 plan if the plan was subsequently used for any nonqualifying expense, including K-12 expenses. This can be done by requiring that a credit be repaid (as in Vermont or Oregon) or that the K-12 expense amount be added back to taxable income, up to the amount of past deductions claimed.

- Levy penalties: States may also levy additional penalties to claw back the tax benefits from deferring taxes on investment returns that are ultimately used for nonqualifying purposes. While the federal government’s 10 percent penalty on non-qualified withdrawals is an effective deterrent for most potential misuses of 529 accounts, it does not apply to K-12-related withdrawals, and thus states wishing to discourage the use of 529 plans for this purpose must apply their own, supplementary penalties. Without such a penalty, some upper-income families will use 529 accounts for private K-12 purposes and will access state tax deferral benefits in the process. Such a penalty is particularly important in states without contribution tax subsidies, as those states can’t rely on clawing back the contribution subsidy as a means of discouraging inappropriate use of these accounts.

Conclusion

529 savings plans were originally created to encourage long-term savings for higher education. While these plans are not perfect, their purpose was broadly popular and well established.

Federal lawmakers radically changed the character of these accounts in 2017 by allowing taxpayers to use them to send their children to private and religious K-12 schools, creating an inefficient and inequitable tax subsidy in the process. Recent changes in 2025 to double the qualifying withdrawal amount for K-12 tuition and expand the pool of qualifying K-12 expenses have created an even more lucrative subsidy aiding wealthy taxpayers who send their children to private schools partially at public expense.

While states cannot prevent the federal government from exempting 529 withdrawals spent on private K-12 education from federal tax, states can ensure that taxpayers using 529 plans for this purpose will not be rewarded with state tax subsidies as well.