Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

The property tax is the oldest major revenue source for state and local governments. At the beginning of the twentieth century, property taxes represented more than eighty percent of state and local tax revenue. While this share has diminished over time as states have introduced sales and income taxes, the property tax remains an important mechanism for funding education and other local services. This policy brief discusses why property is taxed and how property taxes are calculated.

Why Tax Property?

The property tax is rooted largely in the “benefits principle” of taxation. Under this view, the property tax essentially functions as a user-charge on local residents for the benefits they receive from the local policies funded by property taxes. These policies benefit local residents directly in the form of better schools and fire protection, and indirectly in the form of increased housing values.

The property tax also helps differentiate between families of very different means by taxing families with large quantities of wealth more heavily than those without such reserves. But the impact that property taxes can have on low-income families, and particularly the elderly, makes clear that the linkage of the property tax to the ability-to-pay principle is far from perfect.

Finally, the stability and enforceability of the property tax make it among the best options available for providing local governments with a predictable revenue stream that can be used to fund indispensable services like schools, roads, and public safety.

How Property Taxes Work

How Property Taxes Work

Historically, property taxes applied to two kinds of property: real property, which includes land and buildings, and personal property, which includes moveable items such as cars, boats, and the value of stocks and bonds. Most states have moved away from taxing personal property and now impose taxes primarily on real property.

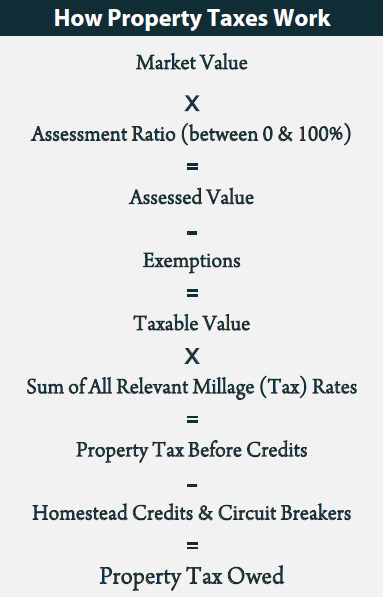

In its simplest form, the real property tax is calculated by multiplying the value of land and buildings by the tax rate. Property tax rates are normally expressed in mills. A mill is one-tenth of one percent. In the most basic system, an owner of a property worth $100,000 that is subject to a 25 mill (that is, 2.5 percent) tax rate would pay $2,500 in property taxes. In reality, however, property taxes are often more complicated than this. The first step in the property tax process is determining a property’s value for tax purposes. In most cases, this means estimating the property’s market value, the amount the property would likely sell for.

The second step is determining the property’s assessed value, its value for tax purposes. This is done by multiplying the property’s market value by an assessment ratio, which is a percentage ranging from zero to one hundred. Many states base their taxes upon actual market value—in other words, these states use a 100 percent assessment ratio. A significant number of states, however, assess property at only a fraction of its actual value. New Mexico assesses homes at 33.3 percent of their market value, and Arkansas uses a 20 percent assessment ratio. Some states place a cap on increases in a home’s assessed value in any given year, which in many cases can lead to vastly different assessment ratios among similarly valued homes (For more detail, see ITEP Brief, “Capping Assessed Valuation Growth: A Primer”). And even when the law says properties should be assessed at 100 percent of their value, local assessors at times systematically under-assess property, reporting assessed values that are substantially less than the real market value of the property.

After the assessment ratio has been factored in, many states reduce a property’s assessed value further by allowing exemptions. The most common type of exemption is referred to as a “homestead exemption.” In Ohio, for example, the state allows an exemption for the first $25,000 of home value. Subtracting all exemptions yields the taxable value of a property. (For more on homestead exemptions, see ITEP Brief, “Property Tax Homestead Exemptions”).

The next step in the process is applying a property tax rate, also known as a millage rate, to the property’s taxable value. The millage rate is usually the sum of several tax rates applied by several different jurisdictions: for example, one property might be subject to a municipal tax, a county tax, and a school district tax. This calculation yields the tentative property tax before credits.

Many states allow property tax credits that either directly reduce the property tax bill, or that reimburse part of the property tax bill separately when taxpayers apply for them. Subtracting these credits is the final step in calculating one’s property tax bill—though taxpayers are often required to pay the pre-credit property tax amount, only to later have the amount of the credit refunded to them. (For more detail on one type of property tax credit, see ITEP brief, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers”).

Other Property Tax Issues

While property taxes on owner-occupied homes tend to receive the most attention, the presence (or absence) of tax on other forms of property also has important implications.

- Businesses pay property taxes just like local residents. Property taxes on businesses are mostly borne by business owners. Business property taxes generally make the property tax less regressive, since business owners tend to be wealthier than average.

- Property taxes also impact taxpayers who rent, rather than own their home. This is because owners of rental real estate pass through some of their tax liability to renters in the form of higher rents. The impact of property taxes on renters is of particular concern because renters tend to be significantly less well-off than their homeowner neighbors.

- Non-profit entities are generally exempt from state and local property taxes. While these exemptions can make it easier for these organizations to pursue their missions, it can mean that local governments have difficulty raising the revenue needed to provide quality public services. This issue is most significant in areas with large non-profit hospitals and/or universities.