Read this Policy Brief in PDF Form

In recent months, lawmakers in a number of states have suggested that a particular type of sales tax, called the value-added tax or VAT, might be a cure-all for state budgetary problems. Although Michigan is the only state that currently relies on a VAT as a major revenue source, several other states have recently considered implementing this type of tax. This policy brief evaluates the case for (and against) implementing a VAT at the state level.

What is a Value-Added Tax?

The value-added tax is exactly what its name implies. It is a tax on the value added at each stage of the production of goods and services. For any firm paying the VAT, the “value added” for a particular item is the amount by which the sales price of the product exceeds the cost of all the products purchased to make that item. Because the tax is paid at each level of production, and often not itemized on the final bill to consumers, some try to characterize the VAT as a tax on business. But most analysts agree that the value added tax is essentially a sales tax on consumer purchases that is collected in stages. From a tax fairness perspective, in other words, a VAT is just like a sales tax—it’s regressive, requiring low-income taxpayers to pay more of their income in tax than wealthier taxpayers must pay. The main difference is that the VAT is collected a little bit at a time from each stage of the production process, rather than being collected in one lump sum at the time of the final retail sale.

The value-added tax is exactly what its name implies. It is a tax on the value added at each stage of the production of goods and services. For any firm paying the VAT, the “value added” for a particular item is the amount by which the sales price of the product exceeds the cost of all the products purchased to make that item. Because the tax is paid at each level of production, and often not itemized on the final bill to consumers, some try to characterize the VAT as a tax on business. But most analysts agree that the value added tax is essentially a sales tax on consumer purchases that is collected in stages. From a tax fairness perspective, in other words, a VAT is just like a sales tax—it’s regressive, requiring low-income taxpayers to pay more of their income in tax than wealthier taxpayers must pay. The main difference is that the VAT is collected a little bit at a time from each stage of the production process, rather than being collected in one lump sum at the time of the final retail sale.

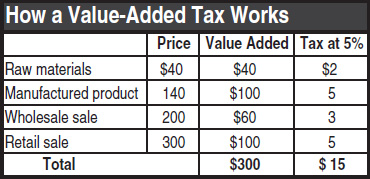

The following example shows how a VAT would apply to the production and sale of a chair:

- First, a supplier sells raw materials (for example, wood) to a manufacturer for use in producing the chair. If the raw materials are sold for $40, the materials supplier pays tax on the whole $40. A 5 percent tax rate on the $40 of value added equals a $2 tax.

- Second, the manufacturer builds the chair and sells it to a wholesaler for $140. The manufacturer pays a VAT only on the value it has added to the chair. Since the manufacturer has taken raw materials worth $40 and made a chair worth $140, the manufacturer’s value added is $100. A 5 percent tax on the $100 value added is $5.

- Third, the wholesaler sells the chair to a retailer for $200. The wholesaler bought the chair for $140 and sells it for $200, so the wholesaler’s value added is $60. The 5 percent tax is $3.

- And finally, the retailer sells the chair for $300. Since the retailer bought the chair for $200 and sold it for $300, the retailer’s value added is $100.

At the end of this process, the outcome from the consumer’s perspective is just the same as if the state had imposed a retail sales tax on the $300 sales price. The main difference is that the VAT is collected a little bit at a time at each stage of the production process, rather than being collected in one lump sum at the time of the final retail sale.

Why Adopt a VAT—and Why Not

Policymakers seeking to impose a state VAT usually have one of two tax policy goals in mind, depending on which existing tax they want to replace. European VATs were created to eliminate structural problems in existing sales taxes. In particular, prior European sales taxes often applied not only to retail purchases but to “business to business” transactions, which should be exempt. When sales taxes apply to these business inputs, the tax is typically passed through to consumers in the form of higher retail prices. In other words, taxing business inputs amounts to taxing consumers multiple times on the same retail purchase. This problem, known as “pyramiding,” makes the sales tax both regressive and unpredictable (because the number of times the tax is paid depends on the number of stages of production), and encourages businesses to “vertically integrate” to avoid paying taxes on inputs to the production process. VATs are especially well designed to avoid taxing business inputs, since each component of a retail product’s value added is taxed exactly once. In other words, European countries replaced their poorly structured sales taxes with a better-functioning sales tax.

In Michigan, the rationale for adopting a VAT was quite different: their VAT was adopted to replace the corporate income tax, not the sales tax. Corporate income taxes tend to fluctuate wildly over the business cycle because they are based on corporate profits, which vary dramatically during periods of economic growth and downturns. Michigan’s corporate tax was especially volatile due to the importance of auto sales to its economy. A VAT is an inherently more stable and predictable revenue source than a corporate profits tax, because the tax base is a firm’s total amount of economic activity, which tends to be less variable than a firm’s profits over time, rather than its profits. In other words, Michigan replaced its corporate profits tax with what amounts to a second sales tax, choosing revenue stability as a primary goal of its “Single Business Tax.”

Problems With a VAT

Each of these rationales has some merit: replacing a sales tax with a VAT will improve the horizontal equity of the sales tax (by ensuring that each retail transaction is taxed the same way), and replacing a corporate profits tax with a VAT will make revenues more stable. But implementing either approach at the state level is problematic, for several reasons:

- What works on a national level in Europe may not work on the state level in the United States. If one state adopts a VAT while neighboring states do not, the inability of states to tax purchases from some out-of-state sellers will mean that some value added won’t be taxed, and sales made to other states will create the same problem. Put another way, a VAT cannot usually work in one state without a lot of help from other states.

- Unlike a retail sales tax, a VAT often isn’t itemized on retail receipts (although it can be). Thus, consumers may be less aware that they are paying a VAT. Invisible taxes make it harder for consumers to see how much they are really paying.

- People don’t understand how VATs work. Calling a VAT a “Single Business Tax” may fool people into thinking that a VAT falls on business rather than consumers.

- Abandoning a corporate profits tax for a VAT makes the tax system less responsive to a business’s ability to pay taxes. This is part of the reason why Michigan’s VAT is currently slated to be repealed by 2009: the VAT is especially painful for businesses not turning a profit.

- Because a VAT is passed through to consumers like a sales tax, replacing a corporate profits tax with a VAT will make already-unfair state tax systems even more regressive.

Value added taxes have been enacted internationally to address important concerns about structural flaws in sales taxes. But as a replacement for corporate profits taxes on the state level, the main impact of a VAT will be a more regressive tax system—and a host of angry businesses.