Table of Contents

Designing a State Tax on Marijuana

How Much Revenue Would Marijuana Legalization Generate for States

Factors that Could Negatively Impact Marijuana Revenue

Factors that Could Positively Impact Marijuana Revenue

Charts and Text Boxes

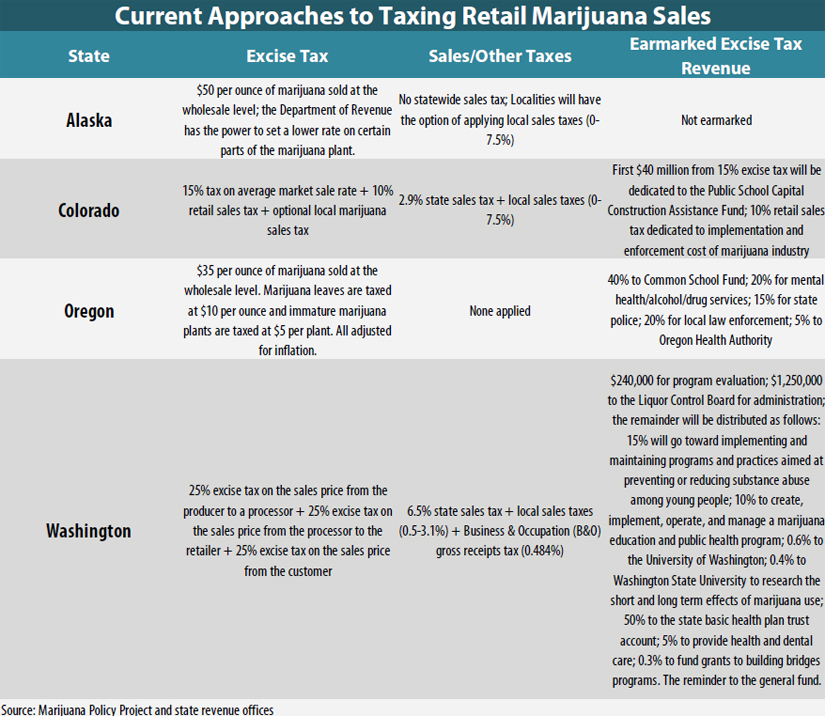

Current Approaches to Taxing Retail Marijuana Sales

How Should Medical Marijuana Be Taxed?

Marijuana Tax Revenue Over Time

Since 1996, when California voters enacted the nation’s first medical marijuana law, twenty-two states and the District of Columbia have followed suit with laws allowing production and use of marijuana for medicinal purposes.[i] In 2014, Colorado and Washington took legalization efforts one step further by implementing systems that allow regulated production and retail sale of marijuana. Oregon, Alaska and the District of Columbia are currently creating their own legalization regimes after the passage of ballot initiatives legalizing marijuana in each jurisdiction last November.[ii] Given the current political momentum, more states may consider marijuana legalization in the future.

While much of the debate around marijuana legalization rightly focuses on health and criminal justice effects, legalization also has revenue implications for state and local governments that choose to tax newly legal purchases of marijuana. This report examines issues surrounding the design and implementation of taxes on marijuana at the state and local level.

Forty-five states levy general sales taxes which, in theory, should apply broadly to most or all retail transactions. Until recently, however, the illegal and unregulated nature of marijuana has resulted in it being sold entirely outside of state sales tax structures. Twenty states have laws requiring illegal marijuana sellers to purchase and place tax stamps on their marijuana, but virtually no one buys the stamps since selling marijuana is illegal even with the stamps attached.[iii]

Now that an increasing number of states are legalizing medical and retail marijuana, the de facto sales tax exemption enjoyed by marijuana is becoming somewhat less common. Eleven states with legalized medical marijuana apply their sales taxes to the product, and the only two states with functioning, legal markets for retail marijuana (Colorado and Washington) each apply their general sales taxes to marijuana as well.[iv] Bringing marijuana out of the black market allows state and local governments to include the product in their sales tax bases in the same manner as most other goods and services.

But appropriate marijuana tax policy could go beyond simply adjusting existing sales tax bases to include the product. Another potential reason to tax marijuana is to mitigate the negative impact of its use by both discouraging its consumption and raising revenue that can be used to offset its social costs.[v] In other words, the tax treat-ment of legalized marijuana could be similar to that of tobacco and alcohol, both of which face significant excise taxes at the federal, state and local levels.

Designing a State Tax on Marijuana

Expanding state and local sales tax bases to include marijuana should be straightforward in most cases: the general sales tax rate can simply be applied to the total cost of the marijuana, or marijuana-containing product, being sold (medical marijuana is a possible exception, discussed below). In contrast, designing the ideal excise tax is more challenging as it requires striking a balance between taxing the product heavily enough to offset its social costs, and not taxing it so heavily so as to result in widespread tax evasion and black market marijuana sales.

Per-Unit Taxation

Typically, excise taxes are applied on a per-unit basis,[vi] rather than as a percentage of the final sale price of the product. For example, cigarettes are currently taxed at $1.01 per pack[vii] at the federal level and $1.54 per pack[viii] on average at the state level.

Alaska[ix] and Oregon are poised to implement a similar approach in the context of marijuana with new excise taxes of $50 and $35 per ounce, respectively. This design is in agreement with model legislation[x] proposed by the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP). Unlike Alaska, Oregon has adopted the MPP’s sensible recommendation to index the tax rate to inflation (at least partially)—meaning that the per-ounce tax rate will gradually rise over time to prevent its real value from being diluted in the face of inflation.

The main advantage of a per-unit tax is that the amount of revenue raised should be fairly stable—especially in the face of the significant drop in marijuana prices that is predicted to follow legalization (see “Legalization’s Effect on Marijuana Prices,” on page 10).

One potential disadvantage of a per-unit tax on marijuana is that it does not take into account the potency of the marijuana being cultivated. Taxing marijuana by its weight does not accurately account for its impact, which experts argue is primarily driven by the drug’s THC content.[xi] A flat, weight-based marijuana tax may inadvertently incentivize producers to cultivate stronger marijuana because it would have a higher sale price, yet still only be subject to the same per-unit tax as lower potency marijuana.

Some experts have proposed that a per-unit excise tax would work more effectively if it was applied to the amount of the intoxicating component contained within a given unit of marijuana, rather than simply the marijuana’s weight.[xii] This approach would mirror the current treatment of alcohol at the federal level, where wine and liquor generally are taxed at a higher rate than beer due to their higher alcohol content.[xiii] For now, however, the technology for measuring THC and other intoxicating agents is not reliable enough to put this kind of system into place.[xiv]

Value-Based Taxation

The only two states that have fully implemented an excise tax on the retail sale of marijuana have opted not for a per-unit tax, but rather for a value-based tax applied at multiple levels of production and sale. Washington, for instance, applies a 25 percent tax on the sale of marijuana from producers to processors, on the sale of marijuana from processors to retailers, and again on retail sales (all on top of the applicable sales and gross receipts taxes).[xv] Colorado subjects marijuana to a 15 percent excise tax on the sale from the producer to the retailer and another 10 percent excise tax on the final sales price, in addition to applying existing state and local sales taxes to the purchase of retail marijuana.[xvi]

The major advantage of a value-based approach is that the tax will automatically adjust to the size of the consumption base to which it applies. In other words, a value-based tax will capture the same percentage of overall spending on marijuana, even as the price of the drug increases or decreases. The potential disadvantage of this from a revenue-raising perspective is that a drop in marijuana prices would dramatically erode the revenue that a value-based tax can raise.

Unlike per-unit excise taxes, a value-based tax on marijuana has the benefit of being more closely linked to the potency of the product being sold. Stronger, more intoxicating marijuana will generally be taxed more heavily under a value-based tax since stronger marijuana is typically more expensive than weaker strains.

One problem with a value-based tax, when it is applied at the wholesale level, is that it has proven difficult to apply to a vertically integrated marijuana industry. In Colorado, marijuana retailers were initially required to cultivate at least 70 percent of the marijuana that they sell. This requirement made it very difficult for tax authorities to determine the wholesale price of marijuana since most marijuana in the vertically integrated industry was being “sold” within the same firm. This difficulty forced regulators to adopt a de facto weight-based system wherein marijuana “sold” at the wholesale level was subject to a tax based on an estimated average per-unit price of marijuana. [xvii]

Tax Rates Over Time

Among the biggest hurdles faced by regulators in Colorado and Washington in creating their legal marijuana markets is the continuing competition from the marijuana black market.[xix] From the outset, marijuana prices on the legal markets have typically been much higher than black market marijuana prices. This creates a strong disincentive against consumers shifting their purchases to the legal market, particularly since most marijuana consumers grew accustomed to shopping in the black market during prior years in which it was the only option available.

One approach that states could take to help shut down the black market is to phase-in the implementation of marijuana taxes gradually as the legal market gets fully up and running. This is the same approach that was taken when federal regulators ended alcohol prohibition in the 1930s.[xx]

But while high marijuana prices may be the bigger problem for regulators in the short-term, very low prices could prove to be the more important issue in the long-term. As the legal marijuana market develops and growers begin to refine their techniques, the price of marijuana could drop significantly and spur an increase in consumption (see “Legalization’s Effect on Marijuana Consumption,” page 10). Considering that one of the potential goals of levying an excise tax is to discourage the consumption of a product, states could consider setting up their marijuana excise tax so that it creates a price floor. For example, if the pretax price of retail marijuana falls to $60 per ounce but state lawmakers want to ensure that marijuana is never cheaper than $100 an ounce, the state could require that the total tax collected at the cash register be the greater of the statutory tax rate, or the tax rate needed to raise the final price to $100 ($40 in this case).

Earmarking Marijuana Tax Revenue

Proponents of marijuana legalization often advocate for earmarking some portion of future marijuana tax revenue to pay for specific public services such as education. For example, the first $40 million each year generated by Colorado’s excise tax has been earmarked for school construction.[xxi] Similarly, the Marijuana Policy Project’s model legislation calls for 30 percent of marijuana tax revenues to be distributed to state departments of education.[xxii]

While earmarking marijuana funds to popular spending initiatives may make political sense, it is not necessarily effective budget policy. One inherent problem with earmarking is that state revenue is typically fungible between different spending areas. Lawmakers can shift other revenues away from the earmarked fund, leaving the overall amount of money spent on that area unchanged.[xxiii]

Additionally, earmarking excise tax revenue can be counterproductive if it creates a substantial incentive for lawmakers to promote the activity that the tax was initially intended to discourage. For example, North Carolina lawmakers approved a doubling of the state lottery’s advertising budget in hopes of encouraging more of their residents to gamble, thereby generating more revenue to help pay for teacher raises.[xxiv]

While most marijuana tax earmarking proposals are made for political reasons, there is a case to be made for directing some revenues toward programs that offset negative externalities created by marijuana consumption. These could include, for instance, treatment programs and state drug public education programs. Excise taxes could also potentially be directed toward the enforcement and oversight of marijuana production, though much of this is already funded through licensing fees on marijuana producers and sellers.[xxv]

|

HOW SHOULD MEDICAL MARIJUANA BE TAXED? Determining the proper tax treatment of marijuana is complicated by the fact that the drug can be used for either recreational or medicinal purposes. While recreational marijuana use is typically thought of as producing negative externalities, marijuana used for medicinal purposes likely is not. This perception of marijuana as medicine plays a large role in its use; a Pew Research poll found that 53 percent of marijuana users say that they use it exclusively or partially for medical reasons.[xviii] Nearly every state in the country exempts prescription drugs from its general sales tax, but very few states exempt non-prescription drugs. At present, medical marijuana is best classified as a non-prescription drug since its lack of approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) means that doctors can only recommend that their patients use marijuana—not formally prescribe it. This suggests that, barring FDA approval, most state sales taxes should apply to medical marijuana, as is the case today. Turning to excise taxes, designating the substance as a medicine suggests that, when used correctly, medical marijuana may confer health benefits on individuals using it. From that perspective, there seems to be little reason to apply a stand-alone excise tax to marijuana. Excise taxes on marijuana are generally thought of as a tool for discouraging the drug’s use or funding programs that can offset its negative societal effects—neither of which seems necessary in the case of medical marijuana. But this distinction could be hard to implement. While there are good reasons for states to tax marijuana used for medical purposes differently than marijuana used for recreational purposes, Colorado’s experience reveals that this disparate treatment can lead to significant tax base erosion. Lower taxes on medical marijuana in Colorado have incentivized consumers to seek out doctors’ recommendations to purchase marijuana at a discount compared to the regular marijuana market. If the standard for doctors recommending marijuana in a given state is not restrictive, then a huge part of the recreational marijuana tax base could disappear as individuals are incentivized to falsely claim a medical need to get the discount. |

How Much Revenue Would Marijuana Legalization Generate for States?

Amount of Revenue

Being Realistic About Marijuana Revenue

Exactly how much revenue could state marijuana taxes raise? This question is difficult to answer because no countries or states have legalized and taxed marijuana for a sustained period of time. In addition, the illegality of marijuana under federal law (and in most states) makes it difficult to collect data on current marijuana consumption, meaning that estimates of even basic data points needed to produce an accurate revenue estimate, like the amount of marijuana consumed or the average price of marijuana in different regions, are not known with certainty.

Current Marijuana Revenue Raised

Given the novelty of marijuana legalization, Colorado and Washington’s monthly marijuana revenue reports have been extensively covered by the media in the hope of gleaning any new information on the tax revenue that marijuana sales will generate today and in the future. In the case of Colorado, the latest data from the state’s Department of Revenue show that Colorado collected $63.4 million in excise and state sales taxes (not including local sales taxes) on retail and medical marijuana during 2014, which constitutes about half a percent of total revenue collection in the state.[xxvi] Although revenue collected was lower than expected at the outset, the amount of revenue collected each month increased substantially from January through December as marijuana sales have ramped up, with the monthly revenue collection going from $2.9 million in January to $7.3 million in December.

For its part, Washington has collected $16 million in state level excise taxes (not including state and local sales taxes or the Business and Occupation Tax) on marijuana from the beginning of July through the end of December 2014.[xxvii] Washington’s lower tax collections in its first few months of legalization were driven by a shortage[xxviii] of legally grown marijuana at dispensaries due to the lengthy amount of time it took the state to implement a regulatory system from scratch. In contrast, Colorado was quicker in getting its regulatory system in place by building on its existing medical marijuana dispensary system.[xxix]

Considering a Ballpark Revenue Estimate

Given the highly unpredictable nature of marijuana legalization across a multitude of factors (many of which are discussed below), any estimates of the amount of revenue that marijuana taxes could raise should be viewed as ballpark figures rather than precise forecasts. That being said, a recent study by Divya Raghavan estimated that applying existing sales taxes and a 15 percent excise tax on marijuana in each state would generate just under $3.1 billion in state tax revenue on an annual basis.[xxx] Similarly, a recent study by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service estimated that a $50 per ounce state level excise tax could raise about $6.8 billion in tax revenue per year.[xxxi]

To give some context, the $3.1 to $6.8 billion range of revenue from marijuana taxes puts this tax in the same revenue ballpark as the $6.5 billion[xxxii] raised by state and local alcohol taxes, but well below the $17.6 billion[xxxiii] raised by state and local cigarette taxes each year.

The remainder of this section will consider a variety of factors that could substantially increase or decrease the level of revenue raised by marijuana taxes.

Factors that Could Negatively Impact Marijuana Revenue

Federal Intervention

For states that are considering legalizing and taxing marijuana, one significant obstacle to accurately forecasting the potential revenue gain is that the production and consumption of marijuana is illegal under federal law.

While federal enforcement of marijuana laws appear to have softened in recent years, it has done so only in limited ways. An August 2013 memorandum issued by the Obama Administration implied that federal prosecutors should not prioritize cases against marijuana consumption and production that are in clear compliance with state law.[xxxiv] Moreover, Congress passed a provision in an omnibus spending bill at the end of 2014 preventing the Department of Justice (DOJ) from using its funds over the next year to prevent states from implementing medical marijuana laws.[xxxv]

The problem for state governments looking forward is that the limits on DOJ’s activities will expire in less than a year, and the Obama Administration or any future administration could reverse course at any time and begin shutting down state-sanctioned marijuana production facilities and retail outlets. While it is unlikely that the federal government would shut down all state sanctioned marijuana sales, stepped up federal enforcement could have a significant impact on the amount of revenue that states can raise.

In addition, opponents of marijuana legalization have and will likely continue to issue legal challenges against the states with legalized marijuana in hopes of shutting down licensed marijuana sellers. For example, the governments of Oklahoma and Nebraska recently filed suit against Colorado in federal court arguing that the state’s marijuana program should be shut down because it is in irreconcilable conflict with federal law.[xxxvi]

One area where fear of federal enforcement is already having a substantial impact is on the banking industry, which has almost universally refused to take money generated from marijuana sales.[xxxvii] The result of this has been to force marijuana dispensaries to operate almost exclusively in cash, which can create significant problems for tax enforcement and make the dispensaries targets for robbery. To deal with this problem, Colorado regulators have set up video surveillance systems in hopes of keeping track of the cash (and marijuana) flow, but it is unlikely this will completely resolve the issue.[xxxviii] Federal intervention via the passage of legislation in Congress like the proposed “Marijuana Businesses Access to Banking Act”[xxxix], which would open up banking to the marijuana industry, could have a significant impact on the financial standing of the marijuana industry and tax enforcement in the states.

Legalization’s Effect on Marijuana Prices

Legalization of large-scale marijuana production techniques could, in the long-term, lead to a drop in marijuana wholesale prices by an estimated 100-fold. For example, a producer of marijuana today sells a pound of marijuana for around $2,000, but with mass production techniques the cost of a pound go down to $20 for low-grade marijuana.[xl] If this occurs, revenues collected from any sales or excise tax tied to the price of marijuana will quickly plummet as well.

In the short term, it is hard to tell how quickly prices will drop given the difficulties associated with creating functional and legal marijuana markets. In Colorado for instance, media reports indicate that legal marijuana’s after-tax price is still above the price of black market marijuana, but that the legal price is expected to drop next year as production ramps up.[xli] Similarly, prices have dropped steadily in Washington.[xlii]

The extent of the drop in marijuana prices would be determined in large part by the extent to which state regulations limit the scale of marijuana production. Even so, the Rand Corporation estimates that prices could still drop by 90 percent through the use of legal small-scale indoor farming.[xliii]

Some advocates of marijuana legalization have argued that falling marijuana prices could be a boon to marijuana tax revenues if the excise tax rate is increased in such a way that marijuana prices essentially stay the same and the government collects the difference. The extent to which state and local governments can actually capture this difference is limited by the incentive for tax evasion that will be created if the tax becomes a very large component of the final sales price, especially if nearby states choose not to substantially increase their excise taxes.[xliv]

Tax Evasion

With any tax, there is always some level of tax evasion that will occur depending on the ease of enforcement and the size of the incentive to evade the tax. Given the lack of experience with taxing marijuana, there is no way to predict the exact degree of excise tax evasion that will occur, though given most marijuana consumers’ familiarity with the black market, there is reason to believe that the potential for evasion is fairly high. Moreover, the high level of cigarette excise tax evasion provides a warning to lawmakers that large enough excise taxes can result in a significant, unregulated and untaxed black market.[xlv] In any case, state lawmakers should be careful to create a robust enforcement regime in order to limit opportunities for tax evasion.

Treatment of Homegrown Marijuana

The ability for individuals to grow their own marijuana on a small scale could have a significant impact on the size of the retail marijuana market. Alaska, Colorado and the District of Columbia each allow individuals to grow up to six marijuana plants per person for non-medical purposes.[xlvi] On July 1, Oregon will allow individuals to grow up to four plants. Of the states where marijuana is allowed for retail sale, only Washington does not allow individuals to grow their own marijuana for non-medical purposes.[xlvii]

It is unclear what portion of the marijuana market will be taken by homegrown marijuana, but if it turns out to be significant it could have a negative impact on the amount of revenue collected since it goes untaxed.

Substitution for Alcohol

Another potential revenue impact of marijuana legalization is the extent to which it would decrease revenue raised by alcohol excise taxes. There is some evidence that marijuana consumption functions as a substitute to alcohol consumption, which means that the revenue raised by alcohol excise taxes could potentially decrease if marijuana is legalized and people begin to consume more marijuana and less alcohol as a result.[xlviii]

|

MARIJUANA TAX REVENUE OVER TIME Estimating the potential revenue yield of marijuana legalization is particularly difficult because that yield is likely to vary substantially over time. For starters, Colorado and Washington State’s experiences show that any revenue gain is likely to be slow in coming to fruition. The first legal retail sale of marijuana in Colorado did not occur until over a year after the state legalized the drug, and in Washington State the delay was over eighteen months. Even after legal sales commenced, revenues were lower than expected in the first few months as a result of regulatory issues and the lingering presence of an untaxed black market. After these initial hurdles are overcome, however, there is reason to believe that marijuana revenues could increase substantially. This is in part because there are relatively few states right now with legal marijuana markets, and thus early adopters of legalization may enjoy some draw as marijuana tourism destinations. In the long-run, however, the tourism draw of marijuana is likely to wear off if more states set up regulated markets for the drug. Moreover if cost-cutting, large-scale farming techniques are eventually implemented, the price of marijuana could drop significantly and thus the revenues collected from any tax based on the price of marijuana will decline as well. Accurately forecasting the revenue yield of marijuana taxes therefore requires careful thought not just about the short-term effects of setting up a regulated system, but also about the long-term trajectory of marijuana prices and demand. |

Factors that Could Positively Impact Marijuana Revenue

Legalization’s Effect on Marijuana Consumption

Adding another layer of complexity to the fiscal outlook, there is no consensus on the long-term effect of marijuana legalization on the overall amount of marijuana consumption. The Cato Institute argues that marijuana consumption would remain roughly the same if marijuana is legalized.[xlix] The Rand Corporation estimates that total marijuana consumption could triple in the long term, but that any estimate on consumption trends is ultimately little more than an educated guess given the lack of historical evidence on this point.

Nonetheless, if it turns out that a substantial increase in marijuana consumption follows from legalization, it is clear that the result would be a larger tax base from which to raise marijuana tax revenues.

Marijuana Tourism

Because so few states have legalized retail marijuana, those states that do are likely to see a significant amount of consumption by out-of-state individuals looking to participate in the state’s legal regime. In fact, a study prepared for the Colorado Department of Revenue found that about 44 percent of metro area and 90 percent of mountain community sales of retail marijuana in Colorado were to out-of-state visitors.[l] Rather than being just a small portion of marijuana sales, Colorado’s experience so far indicates that marijuana sales to tourists could potentially constitute a significant portion of marijuana sales and thus tax revenues. In addition, a study of potential marijuana legalization in Vermont estimated that most sales would likely be to tourists, especially given that seven times as many marijuana users live within fifty miles of the state as compared to the amount of current users within the state.[li]

To be clear, the tax implications of marijuana tourism extend beyond just the impact on marijuana tax revenues. If people are coming into the state specifically because marijuana is legal, the result could be higher revenues from sales of hotel rooms, rental cars, gasoline, restaurant meals, and other items purchased by tourists.

But tourist-driven marijuana revenues may prove to be short-lived if more states legalize retail marijuana sales. Gambling provides a cautionary tale; as more states have legalized gambling, the tourist flow has slowed and the incidence of gambling taxes has shifted away from tourists and toward state residents.[lii] Atlantic City is a case in point, where four of the city’s twelve casinos closed last year and the city’s finances are in such disarray that Governor Chris Christie chose to appoint an emergency manager.[liii] While it is unlikely that any state will become as dependent on its marijuana industry as Atlantic City is on its gambling industry, it is important that lawmakers recognize that tourist-driven marijuana tax dollars are likely to follow a similar pattern.

Legalization’s Impact on Income Tax Revenues

On top of the revenues that could be raised from direct sales and excise taxes on marijuana, legalization could also affect income tax revenue collections. While the income being earned today from illegal marijuana production and sales is generally going unreported, that would change substantially under a system in which producers and sellers are treated as legitimate, regulated businesses.

Additionally, given that as much as half of all marijuana consumed in the United States is imported,[liv] income earned from marijuana production in the United States is likely to increase since legalization will result in more of the product being grown within the country’s borders.

As long as marijuana remains illegal under federal law, the tax implications of marijuana related income is guaranteed to remain complicated. One major issue arises from the fact that Section 280E of the Internal Revenue Code denies businesses the ability to deduct many normal business expenses if the businesses are “trafficking in controlled substances.” Without the ability to deduct these normal expenses, state-sanctioned marijuana businesses have faced income tax rates as high as 75 percent.[lv] Given these high rates, some federal policymakers have proposed[lvi] exempting state-sanctioned marijuana businesses from 280E, but it is unclear if and when such legislation will pass.

There are a variety of goals lawmakers might seek to accomplish in taxing marijuana. The policy choices outlined in this paper will help determine how effectively tax laws achieve these goals. Once the decision to legalize marijuana has been made, lawmakers should think carefully about the variety of approaches available for taxing the drug, and should pay close attention to the growing body of evidence emerging from those states in the beginning stages of regulating and taxing marijuana.

[i] Marijuana Policy Project, Key Aspects of State and D.C. Medical Marijuana Laws, http://www.mpp.org/assets/pdfs/library/Medical-Marijuana-Grid.pdf

[ii] Ballotpedia, Marijuana on the Ballot, http://ballotpedia.org/Marijuana_on_the_ballot#tab=By_year

[iii] NORML, Marijuana Tax Stamp, http://norml.org/component/zoo/category/marijuana-tax-stamp-laws-and-penalties

[iv] Marijuana Policy Project, Medical Marijuana Dispensary Laws: Fees and Taxes, http://www.mpp.org/assets/pdfs/library/FeesAndTaxes.pdf

[v] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, The ITEP Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes, https://itep.org/state_reports/guide2011.php

[vi] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, How Sales and Excise Taxes Work, https://itep.org/itep_reports/2011/07/how-sales-and-excise-taxes-work.php

[vii] Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury, Tax and Fee Rates, http://www.ttb.gov/tax_audit/atftaxes.shtml

[viii] Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, State Cigarette Excise Tax Rates & Rankings, http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0097.pdf

[ix] Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol in Alaska, Full Initiative Text, http://regulatemarijuanainalaska.org/full-initiative-text/

[x] Marijuana Policy Project, Model State Bill to Replace Prohibition with Regulation, http://www.mpp.org/reports/mpps-model-state-bill-to.html

[xi] Caulkins, J., Hawken, A., Kilmer, B., & Kleiman, M. (2012). What If Marijuana Were Treated Like Alcohol. In Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know. New York City: Oxford University Press.

[xii] Hawken, A., Kilmer, B., Kleiman, M., Pfrommer, K., Pruess, J., Shaw, T., & Caulkins, J. (n.d.). High Tax States: Options for Gleaning Revenue from Legal Cannabis. Oregon Law Review,91(4), 1041-1068. http://www.countthecosts.org/sites/default/Options-for-cannabis-revenue.pdf

[xiii] Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury, Tax and Fee Rates, http://www.ttb.gov/tax_audit/atftaxes.shtml

[xiv] Pat Oglesby, Taxing marijuana potency, http://newrevenue.org/2014/02/17/taxing-marijuana-potency-rose-habib/

[xv] Washington State Liquor Control Board, FAQs on I-502, http://lcb.wa.gov/marijuana/faqs_i-502#Financial

[xvi] Colorado Department of Revenue, Marijuana Taxes | Quick Answers, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/tax/marijuana-taxes-quick-answers

[xvii] Pat Oglesby, Colorado‘s Crazy Marijuana Wholesale Tax Base. Center for New Revenue. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2351399

[xviii] Pew Research Center, Majority Now Supports Legalizing Marijuana, http://www.people-press.org/2013/04/04/majority-now-supports-legalizing-marijuana/

[xix] Gene Johnson, Legalizing Marijuana In Washington And Colorado Hasn’t Gotten Rid Of The Black Market, Associated Press. http://www.businessinsider.com/legal-marijuana-in-washington-and-colorado-hasnt-gotten-rid-of-the-black-market-2015-1

[xx] Rand Corporation, Considering Marijuana Legalization: Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions. p. 89. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR864.html

[xxi]Colorado Department of State, Amendment 64: Use and Regulation of Marijuana, http://www.colorado.gov/cs/Satellite?blobcol=urldata&blobheader=application/pdf&blobkey=id&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobwhere=1251834064719&ssbinary=true

[xxii] Marijuana Policy Project, Model State Bill to Replace Prohibition with Regulation, http://www.mpp.org/reports/mpps-model-state-bill-to.html

[xxiii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Uncertain Benefits, Hidden Costs: The Perils of State-Sponsored Gambling, https://itep.org/itep_reports/2011/10/uncertain-benefits-hidden-costs-the-perils-of-state-sponsored-gambling.php

[xxiv] J. Andrew Curliss, NC House budget relies on higher lottery revenues, even with ad restrictions, The News & Observer. http://www.newsobserver.com/2014/06/11/3929116/house-budget-relies-on-increased.html

[xxv] Marijuana Policy Project, Medical Marijuana Dispensary Laws: Fees and Taxes, http://www.mpp.org/assets/pdfs/library/FeesAndTaxes.pdf

[xxvi] Colorado Department of Revenue, Colorado Marijuana Tax Data, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/revenue/colorado-marijuana-tax-data

[xxvii] Washington State Liquor Control Board, Marijuana Daily Sales Activity, http://www.liq.wa.gov/publications/Marijuana/sales_activity/2015-01-20-MJ-Daily-Sales-Activity.xlsx

[xxviii] Trevor Hughes, Marijuana legal, but scarce in Washington, USA Today. http://www.wtsp.com/story/news/2014/09/26/marijuana-washington/16304287/

[xxix] Peter Robison, Price of Legal Pot Plunges 40% in Washington as Shortages Ease, Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-01-07/price-of-legal-pot-plunges-40-in-washington-as-shortages-ease

[xxx] Divya Raghavan, Cannabis Cash: How Much Money Could Your State Make From Marijuana Legalization?, Nerdwallet. http://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/cities/economics/how-much-money-states-make-marijuana-legalization/

[xxxi] Jane G. Gravelle and Sean Lowry, Federal Proposals to Tax Marijuana: An Economic Analysis. http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43785.pdf

[xxxii] Tax Policy Center, State and Local Alcoholic Beverage Tax Revenue, Selected Years 1977-2012. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=399

[xxxiii] Tax Policy Center, State and Local Tobacco Tax Revenue, Selected Years 1977-2012. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=403

[xxxiv] Congressional Research Service, State Legalization of Recreational Marijuana: Selected Legal Issues. http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43034.pdf

[xxxv] Peter Robison, Congress quietly ends federal government’s ban on medical marijuana. Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-medical-pot-20141216-story.html

[xxxvi] Jack Healy, Nebraska and Oklahoma Sue Colorado Over Marijuana Law, New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/19/us/politics/nebraska-and-oklahoma-sue-colorado-over-marijuana-law.html

[xxxvii]Jeffrey Stinson, States Find You Can’t Take Legal Marijuana Money to the Bank, Stateline. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/1/5/states-find-you-cant-take-legal-marijuana-money-to-the-bank

[xxxviii]John Hudak, Colorado’s Rollout of Legal Marijuana Is Succeeding. Brookings. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2014/07/colorado%20marijuana%20legalization%20succeeding/cepmmjcov2.pdf

[xxxix] Congress.gov, H.R.2652 – Marijuana Businesses Access to Banking Act of 2013. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/2652

[xl] Caulkins, J., Hawken, A., Kilmer, B., & Kleiman, M. (2012). What If Marijuana Were Treated Like Alcohol. In Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know. New York City: Oxford University Press.

[xli] Jacob Sullum, This Is What Legalizing Marijuana Did to the Black Market in Colorado, Reason. http://reason.com/archives/2014/10/30/the-lingering-black-market.

[xlii] Bush, Evan, Average price of legal pot drops to about $12 a gram. The Seattle Times. http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/marijuana/average-price-of-legal-pot-drops-to-about-12-a-gram/

[xliii] Kilmer, B., Caulkins, J., Pacula R.L., MacCoun, R.J., & Reuter, P.H.. Altered State?: Assessing How Marijuana Legalization in California Could Influence Marijuana Consumption and Public Budgets. Rand Corporation. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/occasional_papers/2010/RAND_OP315.pdf

[xliv] Caulkins, J., Hawken, A., Kilmer, B., & Kleiman, M. (2012). Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know. New York City: Oxford University Press.

[xlv] Jonathan P. Caulkins, Eric Morris, & Rhajiv Ratnatunga, Smuggling and Excise Tax Evasion for Legalized Marijuana. Rand Corporation. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/2010/RAND_WR766.pdf

[xlvi] State of Colorado, Marijuana Retailers & Home Growers. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/marijuanainfodenver/marijuana-retailers-home-growers. Ballotpedia, Marijuana on the Ballot, http://ballotpedia.org/Marijuana_on_the_ballot#tab=By_year

[xlvii] Washington State Liquor Control Board, FAQs on I-502. http://lcb.wa.gov/marijuana/faqs_i-502#Licenses

[xlviii] D. Mark Anderson and Daniel I. Rees, Medical Marijuana Laws, Traffic Fatalities, and Alcohol Consumption. IZA DP No. 6112. http://ftp.iza.org/dp6112.pdf

[xlix] Jeffrey Miron and Katherine Waldock, The Budgetary Impact of Ending Drug Prohibition. Cato Institute. http://www.cato.org/publications/white-paper/budgetary-impact-ending-drug-prohibition

[l] The Marijuana Policy Group, Market Size and Demand for Marijuana in Colorado. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/Market%20Size%20and%20Demand%20Study,%20July%209,%202014%5B1%5D.pdf

[li] Rand Corporation, Considering Marijuana Legalization: Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions. p. 89. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR864.html

[lii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Uncertain Benefits, Hidden Costs: The Perils of State-Sponsored Gambling . https://itep.org/itep_reports/2011/10/uncertain-benefits-hidden-costs-the-perils-of-state-sponsored-gambling.php

[liii] Patrick McGeehan, Christie Uses Executive Order to Appoint an Emergency Manager in Atlantic Cit, New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/23/nyregion/christie-uses-executive-order-to-appoint-an-emergency-manager-in-atlantic-city.html

[liv] Library of Congress, Marijuana Availability in the United State and Its Associated Territories. http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/pdf-files/MarAvail.pdf

[lv] Marielys Rosado Barreras, IRC § 280E — An Albatross For Marijuana Industry. Law 360. http://www.law360.com/articles/519253/irc-280e-an-albatross-for-marijuana-industry

[lvi] Congress.gov, H.R.636 – America’s Small Business Tax Relief Act of 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/636