The federal tax system treats income from capital gains more favorably than income from work. A number of state tax systems do as well, offering tax breaks for profits realized from local investments and, in some instances, from investments around the world. As states struggle to cope with short- and long-term budget deficits and to devise strategies to promote economic development in a sustainable fashion, policymakers should assess whether preserving such tax preferences is in the public interest. This policy brief explains state capital gains taxation and examines the flaws in state capital gains tax cuts.

What Are Capital Gains?

Capital gains are profits from the sale of assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate and antiques. Income tax on capital gains is paid only when the asset is sold. Thus, a stock holder who owns a stock over many years does not pay any tax as it increases in value each year. When the stock is sold, the “realized” capital gain is calculated by taking the difference between the original buying price and the selling price.

Federal tax law (and most states) recognize two different types of capital gains: short-term and long-term. Short-term capital gains are generally defined as gains realized on assets that were owned for less than one year. Most capital gains tax breaks are designed to reward long-term asset holding only.

Who Receives Capital Gains?

According to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), only 8 percent of Americans reported net capital gains income on their federal tax returns in 2013—and the vast majority of these gains were realized by the very wealthiest Americans. In particular:

- Taxpayers with federal adjusted gross incomes (AGI) in excess of $200,000 reported close to 80 percent of taxable capital gains, even though they accounted for less than four percent of all returns filed.

- The very wealthiest 0.1 percent of Americans—taxpayers with AGI over $2 million—received almost half, or 49 percent, of all capital gains income.

- The poorest three-fourths of the population—taxpayers with AGI of $75,000 or below— collectively received just under 8 percent of all capital gains income.

In fact, capital gains are among the most unequally distributed sources of personal income. One obvious consequence of this concentration of capital gains income is that any “across the board” capital gains tax cut will dramatically reduce the share of income taxes paid by the very wealthiest taxpayers—and will increase the share of taxes paid by lower- and middle-income taxpayers.

Federal Law Provides Large Capital Gains Tax Breaks

Throughout most of its existence, the federal income tax has offered special treatment for long-term capital gains. Most often, these tax breaks have taken the form of income tax deductions through which taxpayers can subtract some of their capital gains income from their taxable income before calculating their income tax. At other times, federal tax law has provided a special lower tax rate for capital gains.

One of the greatest achievements of the federal Tax Reform Act of 1986 was to remove these special breaks, taxing realized capital gains at the same rate as wages, dividends, and other income. (Previously, 60 percent of realized capital gains had been exempt.) In the years after 1986, however, Congress gradually reintroduced special tax preferences for capital gains income. In 2003, for example, President George W. Bush signed legislation that gradually reduced the top tax rate on long-term capital gains to just 15 percent—less than half the top rate on regular earned income.

Following the expiration of that cut and the creation of an additional 3.8 percent “net investment income tax” to fund health care reform under President Barack Obama, the rate on long-term capital gains income has since risen to 25 percent. While this increase represents an incremental improvement, the large discrepancy between tax rates on earned income versus capital gains shifts the federal income tax away from wealthy investors and toward ordinary wage earners.

Practices and Trends in State Capital Gains Taxation

Nine states (Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin) now provide their own tax breaks for all long-term capital gains income. Other states—such as Colorado, Idaho, Louisiana, and Oklahoma—offer tax reductions for gains from assets located solely within state boundaries, though some of these breaks have sparked legal questions relating to whether they unconstitutionally interfere with interstate commerce. Still other states tailor their capital gains preferences toward specific industries, such as technology businesses in Virginia or the livestock industry in Kansas.

State lawmakers around the country have taken differing approaches to capital gains tax preferences in recent years. Arizona’s tax exemption was enacted in 2012 and Arkansas voted to expand its exemption in 2013. Other states, however, have begun to reconsider such tax preferences. In the last few years, Rhode Island eliminated its preferential tax rates on capital gains while Vermont and Wisconsin each reduced their capital gains exclusions.

State Capital Gains Tax Preferences Are Regressive

According to ITEP’s Who Pays? report, every state’s tax structure is regressive, asking more of low- and moderate-income families than of the wealthy. Special tax breaks that favor investors’ capital gains income over the wages and salaries earned by working families only serve to exacerbate this problem.

For instance, South Carolina’s 44 percent exclusion for all long-term capital gains income drains roughly $127 million from state coffers each year while providing no benefit to the vast majority of the state’s residents. Putting aside the federal tax interactions described below, more than 96 percent of the benefits of this exclusion flow to the wealthiest 20 percent of South Carolinians, and 66 percent flow to the top 1 percent of earners alone.

State Capital Gains Tax Preferences: A Flawed Strategy for Growth

Given the consequences of capital gains tax breaks for both state budgets and tax fairness, it is only natural to wonder why states might include such preferences in their tax codes. The argument that proponents of preferential treatment for capital gains make most frequently is that it is necessary to foster investment and to spur economic growth. Yet, that argument has at least two serious flaws.

First, an array of experts—from economists within the federal government to non-partisan analysts outside it—agrees: there is little connection between lower capital gains taxes and higher economic growth in either the short-run or the long-run. Whatever connection may exist is even more tenuous at the state level. A general state capital gains tax break is highly unlikely to benefit that state’s economy, since any new investment encouraged by the capital gains break could take place anywhere in the United States or the world.

Second, a substantial part of any state capital gains tax break will never find its way to the pockets of state residents. Because state income taxes can be written off on federal tax forms by those taxpayers who itemize their federal income tax deductions, and because the ability to do so is most valuable for the wealthy Americans who realize the bulk of capital gains income, any reduction in state capital gains taxes will be partially offset by an increase in federal income tax liability.

Second, a substantial part of any state capital gains tax break will never find its way to the pockets of state residents. Because state income taxes can be written off on federal tax forms by those taxpayers who itemize their federal income tax deductions, and because the ability to do so is most valuable for the wealthy Americans who realize the bulk of capital gains income, any reduction in state capital gains taxes will be partially offset by an increase in federal income tax liability.

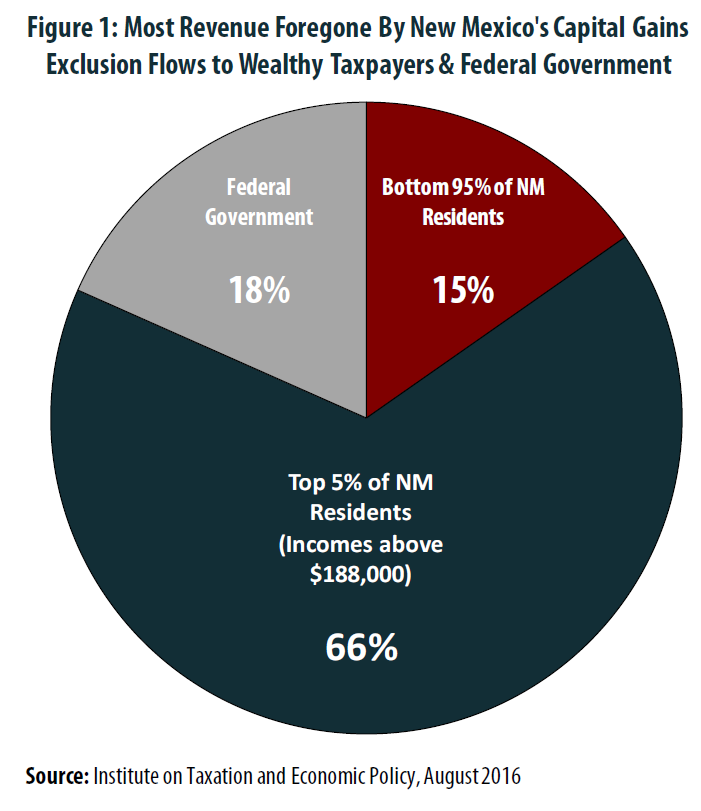

For example, 18 percent of the state revenue losses from New Mexico’s capital gains exclusion are directly offset by higher federal income taxes. Few policymakers would propose an economic development program that directed 18 percent of its budget out of state—yet that is essentially what lawmakers are doing when they argue for a capital gains tax break. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, the share of New Mexico’s capital gains tax break flowing into the federal government’s coffers actually exceeds the share received by the bottom 95 percent of New Mexico residents combined.

Conclusion

Capital gains tax preferences are costly, inequitable, and ineffective, depriving states of millions of dollars in needed funds, benefitting almost exclusively the very wealthiest members of society, and failing to promote economic growth in the manner their proponents claim. States cannot afford to maintain these tax breaks any longer, and lawmakers considering introducing or expanding these regressive policies should understand the fairness and revenue implications before allowing these seriously flawed policies into their tax codes.