Why the Estate Tax is Important

For years, wealth and income inequality have been widening at a troubling pace. A recent study estimated that the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans held 42 percent of the nation’s wealth in 2012, up from 28 percent in 1989.[1] Public policies have exacerbated this trend by taxing income earned from investments at a lower rate than income from an ordinary job and by dramatically cutting taxes on inherited wealth. Further, lawmakers have done little to stop aggressive accounting schemes designed to avoid the estate tax altogether.

Inheritances account for 40 percent of all wealth and 4 percent of annual household income.[2] Researchers have estimated that differences in inheritances explain about 30 percent of the correlation between parent and child incomes — more than IQ, schooling and personality combined.[3] The estate tax is one tool to moderate the accumulation of dynastic wealth and level the playing field between those who inherit wealth and those who depend primarily on earned income.

In the end, the estate tax is about fairness. The wealthiest families benefit the most from what the government provides: public investments such as roads that make commerce possible, public schools that provide a productive workforce, the stability provided by our legal system and armed forces, the protection of private property. These public investments make America a place where families can earn and sustain huge fortunes.

Tax is Concentrated on the Wealthiest Estates

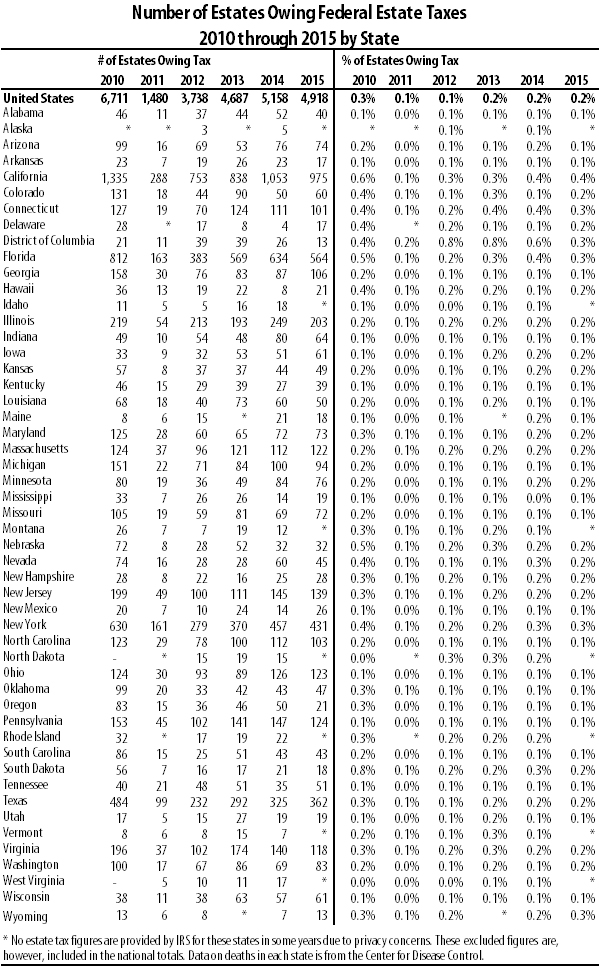

The latest data from the IRS show that only 0.2 percent — just two-tenths of one percent — of deaths in the United States in 2014 resulted in federal estate tax liability in 2015. (Estate taxes are usually filed the year after a person dies.) Put another way, 99.8 percent of estates are exempt from paying even a penny in federal estate taxes. Currently, the first $5.45 million of an estate’s value is exempt ($10.9 million for a married couple), so estates valued under this amount owe no tax at all.[4] As the chart “Number of Estates Owing Federal Estate Taxes 2010 through 2015 by State” at the end of this report shows, the proportion of estates affected by the federal tax in each state is similar to the nationwide percentage.

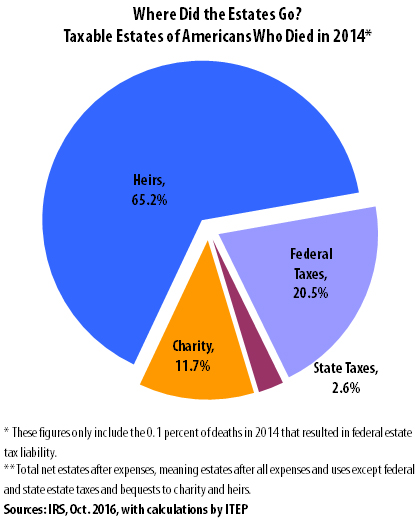

While the statutory estate tax rate is 40 percent, after exemptions and deductions the effective federal rate for estates subject to the tax averaged 21 percent in 2015. The chart below shows that another 3 percent of taxable estates went to state taxes, 12 percent was left to charity, and more than 65 percent of the value of those estates was left to heirs.

Legislative Changes and the Dwindling Reach of the Estate Tax

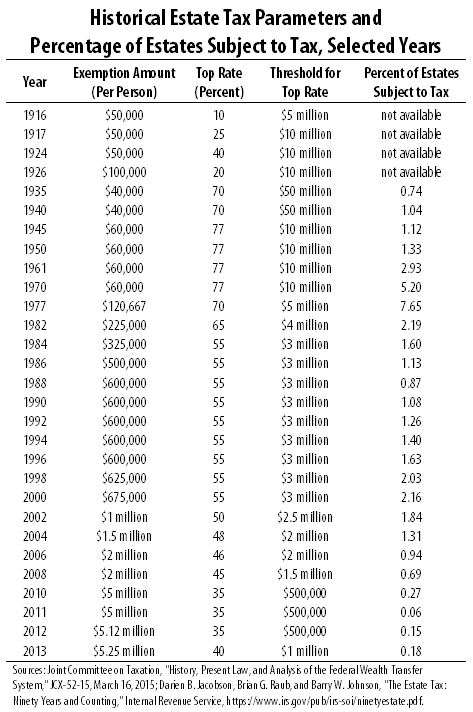

While the estate tax has always been limited to a relatively small number of estates, the percentage of deaths resulting in estate tax liability has fluctuated over time due to inflation (as the exemption amounts were not indexed to inflation until recently) and legislative changes to the parameters of the tax. From the time the U.S. enacted the estate tax one century ago, the portion of estates subject to the tax grew until it reached a peak in the mid-1970s at more than 7 percent. The number then fell throughout the 1980s as lawmakers increased the exemption, and the number rose again through the next decade.

While the estate tax has always been limited to a relatively small number of estates, the percentage of deaths resulting in estate tax liability has fluctuated over time due to inflation (as the exemption amounts were not indexed to inflation until recently) and legislative changes to the parameters of the tax. From the time the U.S. enacted the estate tax one century ago, the portion of estates subject to the tax grew until it reached a peak in the mid-1970s at more than 7 percent. The number then fell throughout the 1980s as lawmakers increased the exemption, and the number rose again through the next decade.

While the exemption amount had been steady at $600,000 since the late 1980s, legislation enacted in 1997 allowed for its incremental increase. Then, in 2001, the first round of President George W. Bush’s tax cuts included the gradual repeal of the federal estate tax over several years. The amount of estate value exempt from the tax increased over time, and the tax rate decreased over time, until the federal estate tax disappeared in 2010.

Like all the Bush tax cuts, this break from the estate tax was scheduled to expire at the end of 2010, at which time the pre-Bush rules were scheduled to come back into effect. President Barack Obama and Congress agreed to a compromise at the end of 2010 to (among other things) extend the Bush income tax cuts and partially extend Bush’s estate tax cuts. As part of this deal, lawmakers reinstated the estate tax but with a higher basic exemption of $5 million per spouse and a rate of just 35 percent in 2011 and 2012. Just 0.1 percent of deaths in 2011 resulted in estate tax liability in 2012. As part of the fiscal cliff deal reached at the end of 2012, Congress permanently extended the higher basic exemption level, indexed it to inflation, and increased the rate from 35 percent to 40 percent.

These changes have led the current tax to be far weaker than in the past. With 0.2 percent of estates currently paying anything, the tax reaches a small fraction of the estates than the historical average of one to two percent. For a more detailed breakdown see the chart “Historical Estate Tax Parameters and Percentage of Estates Subject to Tax, Selected Years” below.

Debunking Estate Tax Myths

There are several arguments that opponents of the estate tax make to support efforts to repeal it. Some claim that because the deceased has already paid income and payroll taxes on his or her accumulated wealth, the estate tax constitutes double-taxation. Another argument is that the estate tax hinders economic growth. And perhaps the most commonly cited objection is that the tax imposes large burdens on heirs inheriting small family farms and businesses.

The Double Taxation Argument

The double taxation argument is problematic for a number of reasons. The most obvious is that the estate tax effectively falls on the heir, who has not paid any previous taxes on these assets and for whom the inheritance is basically a windfall of unearned income. Another important point is that a large portion of the value of many estates consists of unrealized capital gains that have not been previously taxed due to the “stepped-up basis” rule, which resets the base value of assets held until death when they are transferred to an heir (thus, the heir only owes taxes on any appreciation occurring after the inheritance). In fact, for estates worth more than $100 million, unrealized capital gains make up around 55 percent of the total value.[5] Without the estate tax, wide swaths of capital gains income would be 100 percent tax-free. Finally, even the portion of the estates that has been previously taxed was likely taxed largely at preferential rates, since much of the income of wealthy taxpayers is in the form of investment income like capital gains and dividends.

The Economic Growth Argument

Another popular talking point among opponents is that the estate tax leads to a lower rate of capital accumulation and creates a drag on economic growth. The reasoning is that, knowing that a large portion of their wealth will be taxed upon their death leaving less to pass on to heirs, the owners of estates will have less of an incentive to work and save. In other words, the estate tax results in a bias away from savings and investment and toward greater consumption. A reduction in savings, it is argued, leads to a reduction in capital accumulation, which in turn leads to an increase in the return to capital and a decrease in wages. This argument wrongly assumes that the size of an individual’s bequest to heirs is a key determinant of labor and savings decisions. Alternatively, people may base these decisions on their perceived need for retirement savings or other factors. Evidence suggests that there are a variety of bequest motives, or reasons for leaving wealth to heirs, and that these motives likely vary across households.[6] Not all motives are altruistic (e.g. related to the heirs’ well-being), and only in the case of altruistic bequest motives is there a direct connection between the tax rate and the size of the wealth transfer. Indeed, a range of empirical research on the proportion of bequests that have altruistic motives converges around an estimate of only 20 percent.[7]

Another economic consideration is how the size of an inheritance influences heirs’ labor supply decisions. Research has shown that those who receive larger inheritances work less over the course of their lifetimes.[8] Thus, to the extent that the estate tax reduces the amount of wealth left to heirs, this will create an incentive to work more. This increase in productivity will then positively influence economic growth.

The Small Business and Family Farm Argument

Supporters of efforts to repeal the estate tax argue that heirs to family-owned businesses or farms may be forced to liquidate to cover the tax liability on an inherited estate. In reality, only about 20 small farms and businesses (valued between $5 million and $10 million), and only 120 farms and businesses in total were estimated to be subject to the estate tax in 2013.[9] The estate tax law includes special provisions to mitigate any harm on family-owned farms and business, including an option to value a property at its “current-use value” rather than its fair-market value and an option to pay the tax in installments over 14 years. In 2013, only 3 percent of estates with positive estate tax liability utilized this deferral option and only 1.4 percent opted for the alternative property valuation.[10] In 2001, when the exemption amount was much lower and the top estate tax rate had stood at 55 percent or higher for the past 70 years, the American Farm Bureau Federation – a leading advocate of repealing the estate tax – could not report a single case of a family losing a farm due to the estate tax.[11] Clearly, the story of the family resorting to selling a property due to the burden of the estate tax is not the problem it is often made out to be.

Moving Forward

With the estate tax under existential threat, a top priority for tax justice advocates should be to protect this progressive tax to prevent further increases in inequality as well as to preserve needed revenue. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that repealing the estate tax would cost about $269 billion over 10 years.[12] While the estate tax makes up a small portion of federal receipts as a whole, the loss of this revenue would mean either offsetting cuts to federal spending or further deficit increases.

A better option than simply retaining the estate tax in its current form would be to strengthen it by decreasing the exemption amounts, allowing fewer wealthy estates to go untaxed. President Obama included in his latest budget proposals the restoration of the parameters that were in effect in 2009, including a per-spouse exemption of $3.5 million and a top rate of 45 percent. This plan would raise over $161 billion over a decade.[13] Senator Bernie Sanders has also proposed a bill (the Responsible Estate Tax Act), endorsed by then-Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, that would reinstate the $3.5 million exemption and apply graduated tax rates depending on the size of the estate, ranging from 40 percent to 65 percent.

Both the Obama and Sanders plans would also narrow a major loophole in the estate and gift taxes relating to the use of a vehicle known as the Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT). A person owning an asset with a quickly rising value may want to “lock in” its current value for purposes of calculating estate and gift taxes before it rises any further. One way is to place the asset in a GRAT, which pays an annuity for a certain time and then leaves the remaining assets to the trust’s beneficiaries. The gift to the beneficiaries is valued when the trust is set up rather than when it’s received by the beneficiaries. This benefit is particularly difficult to justify when the trust has a very short term, and wealthy people have used such short-term trusts to aggressively reduce or even eliminate any tax on gifts to their children. The proposals would require a GRAT to have a minimum term of 10 years, increasing the chance that the grantor will die during the GRAT’s term and the assets will be included in the grantor’s estate and thus subject to the estate tax.

Policymakers should also eliminate the “stepped-up basis” loophole and instead tax capital gains at death. This means that the capital gains tax would be paid by the estate prior to the transfer of the assets to the heir. Another way to reform this loophole would be to enact “carryover basis” so that when an heir sold an inherited asset, tax would be owed on the appreciation since the asset was originally acquired by the decedent. However, this would be administratively more complex, and would perpetuate the “lock-in effect” where individuals hold onto assets until death to avoid income taxes. Eliminating the stepped-up basis loophole would be even more vital if the estate tax is repealed, since large amounts of capital gains income would otherwise go completely untaxed without the estate tax to provide a backstop.

At a time when wealth is highly concentrated at the top and the nation is facing substantial annual deficits, a robust estate tax serves as a critical device to mitigate growing levels of inequality and provides a stable revenue stream to support necessary public investments.

[1] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence From Capitalized Income Tax Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 131, no. 2 (May 2016), pp. 519–578, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw004.

[2] Lily Batchelder, “The ‘silver spoon’ tax: how to strengthen wealth transfer taxation,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, October 31, 2016, http://equitablegrowth.org/tax-finance/silver-spoon-tax/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This exemption amount is offset by gifts made during one’s lifetime above an annual exclusion amount. Current law also allows for a handful of deductions, such as transfers to a surviving spouse, bequests to charity, funeral expenses, and state inheritance or estate taxes.

[5] Chuck Marr, Brandon DeBot and Chye-Ching Huang, “Eliminating Estate Tax on Inherited Wealth Would Increase Deficits and Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 13, 2015, http://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/eliminating-estate-tax-on-inherited-wealth-would-increase-deficits-and?fa=view&id=5293.

[6] William G. Gale and Joel Slemrod, “Overview,” in Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation, (William G. Gale, James R. Hines Jr., and Joel Slemrod eds.), 2001, pp. 19-23.

[7] Lily Batchelder, “What Should Society Expect from Heirs? A Proposal for a Comprehensive Inheritance Tax,” New York University Law and Economics Working Papers, Paper 152, September 2008, pp. 41-44, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/13524456.pdf.

[8] Wojciech Kopczuk, “Taxation of Intergenerational Transfers and Wealth,” NBER Working Paper 18584, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2012, pp. 41-43, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18584.pdf.

[9] Tax Policy Center, “Current Law Distribution of Gross Estate and Net Estate Tax by Size of Gross Estate, 2013,” January 9, 2013, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/estate-tax-tables-2012/current-law-distribution-gross-estate-and-net-estate-tax-3.

[10] Joint Committee on Taxation, “History, Present Law, and Analysis of the Federal Wealth Transfer System,” JCX-52-15, March 16, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4744.

[11] David Cay Johnston, “Talk of Lost Farms Reflects Muddle of Estate Tax Debate,” The New York Times, April 8, 2001, http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/08/us/talk-of-lost-farms-reflects-muddle-of-estate-tax-debate.html.

[12] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Description Of An Amendment In The Nature Of A Substitute To The Provisions Of H.R. 1105, The ‘Death Tax Repeal Act Of 2015,’” March 24, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4761.

[13] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Proposal,” March 24, 2016, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4902.