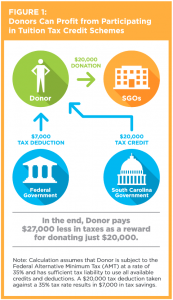

In nine states, tax rewards gained by donating to fund private K-12 vouchers are so oversized that “donors” can turn a profit. This is the shocking but true finding of a pair of studies released by ITEP over the last year (the latter of which was co-authored with the School Superintendents Association, or AASA).

In response to this research EdChoice, a pro-voucher organization, published a new brief intended to undermine valid criticisms of private school tax subsidies. But the brief concedes ITEP and AASA’s central argument on page one: for some private school donors, “the reduction in tax liability can exceed the amount they contributed.” In other words, for some, “donating” to voucher programs requires no personal sacrifice and the financial benefits of a charitable contribution are larger than the costs.

EdChoice attempts to recast ITEP’s findings to make them appear less alarming. This effort takes three main forms, each of which is addressed in this response:

- Erroneously claiming that hundreds of other tax credits can be used as tax shelters in the same manner as voucher tax credits.

- Temporarily pretending that the federal Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) does not exist to create an irrelevant “base comparison” under which “there is no so-called ‘profit.’”

- Mischaracterizing the pool of donors who are eligible to turn a profit via this tax shelter.

Voucher Tax Shelters Are Highly Unusual and Not Comparable to Most Tax Credits

EdChoice asserts that it is “inconsistent” for ITEP and AASA to criticize voucher tax credits without also investigating “hundreds of state and federal tax-credit programs to incentivize charitable giving” of other types. But this reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how most tax credits operate. There are problems with voucher tax credits that simply do not exist in the vast majority of tax credit programs.

The researchers at EdChoice went to great lengths to compile a list of 180 tax credit programs offered in states that also offer voucher tax credits, and they highlight 23 credits in particular that they say “will also be susceptible to the claims proposed in the AASA/ITEP report.” This is simply untrue. A review of this list shows vanishingly few opportunities for taxpayers to turn a profit by claiming tax subsidies that exceed their actual expenses.

For instance, the EdChoice brief draws attention to adoption credits in Indiana, Iowa, Kansas and Montana. It focuses particularly on Indiana’s credit, which it inaccurately describes as equaling 110 percent of the federal adoption credit (the true amount is 10 percent). But for any of these credits’ tax avoidance potential to rival that of voucher tax credits, it would have to be true that beneficiaries of these credits (adoptive parents) are somehow turning a profit off their decision to do what the credits encourage (adopt a child). Clearly, this is an absurd assertion. In all of these states, the long-run financial cost of adopting a child far exceeds the tax benefits. Simply put, adoption tax credits, unlike voucher credits, do not offer a profitable tax shelter.

Comparisons to other tax credits in EdChoice’s list are similarly far-fetched. For instance, its brief spotlights Oklahoma’s Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit, which offers a 20 percent reimbursement for costs associated with rehabilitating a historic building. When combined with the federal government’s 20 percent credit, this means that the government is willing to cover up to 40 percent of the cost of a historic rehabilitation. The other 60 percent, however, must be paid by the person doing the rehabilitation. This is a fairly typical tax incentive structure, designed to encourage people to direct their own money and efforts into specific causes. Again, there is no tax shelter here wherein contractors are receiving tax cuts larger than the expenses they incur.

The vast majority of credits in EdChoice’s list are similarly incomparable to voucher tax credits. A detailed review of every credit is beyond the scope of this discussion. But to take just a couple more examples: it should be obvious to most readers that Alabama’s $1,000 tax credit for employers who hire veterans, or Montana’s $500 credit for residents who install renewable energy systems, are nowhere near large enough to pay out a profit above and beyond the costs associated with becoming eligible for these credits.

While there may be a handful of tax credits in EdChoice’s catalogue that bear some resemblance to voucher tax credits, they are few and far between, and the organization’s brief fails to distinguish them from the slew of irrelevant tax credits it chose to highlight.

A more comparable list of credits would be far shorter and less dramatic than the confused data dump undertaken by EdChoice. From a preliminary review of their list, it appears that Arizona’s $400 credit for contributions to qualifying charitable organizations, and Montana’s $150 credit for innovative educational programs may offer some limited profit opportunities to donors in those states. But these credits are far smaller and less lucrative than the typical voucher tax credit. Despite EdChoice’s best efforts to redirect attention toward other state tax credit policies, voucher tax credits remain the poster child of this particular brand of tax shelter.

The Profit Incentive is Real, and the AMT Exists

EdChoice’s brief includes a lengthy discussion of the technical workings of voucher tax shelters. This discussion centers on the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which is designed to ensure that taxpayers receiving generous tax breaks pay at least some minimum level of federal income tax. Our research has explained in detail that the most common form of voucher tax shelter (but not the only one) amounts to a way to dodge the AMT.

EdChoice argues that the profits being earned by donors are less problematic than they appear because even after profits are received, these donors still pay federal tax bills under ordinary income tax rules. The organization demonstrates this point in a table on page 7 showing that the profiting donor’s final tax liability is no different than it would have been if the AMT did not exist. In a confusing twist, EdChoice argues that its hypothetical “non-AMT scenarios” are an “equally valid” baseline against which to measure profits, even though this baseline is not reflective of federal law.

In determining whether a profit opportunity exists, it is necessary to look at the incentives potential donors face at the margin. The AMT plays a major role in determining the structure of those incentives, and scrubbing it from the baseline of this type of analysis, as EdChoice suggests, is highly confusing—perhaps intentionally so.

Taxpayers paying the AMT in nine states with voucher tax credits are being offered an opportunity to turn a profit if they choose to donate to support K-12 private school vouchers, regardless of whether they personally favor vouchers. How much tax those individuals and businesses pay before, or after, making the donation is irrelevant to calculating whether a profit is being offered at the margin. If any taxpayer finds herself in a situation where the tax cuts being paid out are larger than the donation she is being asked to make, then the concept of “charity” has been thrown out the window, replaced instead with a clear opportunity to turn a profit by agreeing to fund private K-12 vouchers.

Profits Are Reserved for High-Income Taxpayers

As with many tax loopholes, the voucher tax shelter is not geared toward ordinary taxpayers. While EdChoice concedes that “taxpayers subject to the AMT have relatively high incomes,” the organization also seeks to downplay this fact by describing the AMT population as “middle- and upper-middle-class taxpayers.”

The bulk (71 percent) of AMT returns are filed by taxpayers with incomes between $200,000 and $500,000 per year. Because the average tax return reported an income of just $65,751 in 2014, this means that most AMT payers earn between 3 and 7 times as much as the average American household. In other words, these taxpayers are far above the “middle” of the income distribution.

EdChoice also seeks to downplay the fact that very-high-income taxpayers can also turn substantial profits via voucher tax shelters. The organization notes that just 11 percent of AMT filers earn more than $500,000 per year, but ignores the fact that 39 percent of AMT revenue collections come from this group. AMT payers earning less than $500,000 per year pay an average AMT of $4,567, while AMT payers above this income cutoff pay an average of $24,472. This difference in the size of these groups’ AMT liability means that although most taxpayers eligible to profit may fall in the $200,000 to $500,000 range, the largest potential profits are reserved for taxpayers with much higher incomes. This is an especially critical point in states such as Alabama, South Carolina, and Virginia that allow for very high tax credit payouts per donor.

Moving Forward

Profiting from faux donations at taxpayer expense is highly problematic, but it doesn’t have to be this way. EdChoice argues that there is a “simple fix” of the tax code that could be enacted to shut down the profit opportunities revealed in ITEP and AASA’s research. In fact, EdChoice’s suggested fix (gutting the AMT by allowing AMT payers to deduct their state tax liability) is far more sweeping than is needed. But the basic notion that this problem is fixable is undoubtedly true.

As ITEP and AASA have explained: “legislation should be introduced that would specifically bar any federal charitable tax deduction for contributions to voucher nonprofits that were already reimbursed with a state tuition tax credit.” In other words, federal charitable deductions should be reserved for genuine charitable gifts where the taxpayer is measurably worse off, financially, after making the gift. Regardless of your view on private school vouchers, this should be something we can all agree on.