Read the Full Report Including Appendices in PDF

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important functions of government is to maintain a high-quality public education system. In many states, however, this objective is being undermined by tax credits and deductions that redirect public dollars for K-12 education toward private schools. Twenty states currently divert a total of over $1 billion per year toward private schools via special tax credits and deductions.[1] These tax subsidies are essentially backdoor voucher programs, or “neovouchers,” as they use the tax code to provide what amount to private school vouchers even when traditional voucher programs are unpopular with the public or outright unconstitutional.[2]

Because of the ways that state and federal tax law interact, the subsidies offered in nine of these states turn the concept of a charitable “donation” on its head by offering upper-income taxpayers a risk-free profit on contributions they make to fund private school scholarships. In these cases, even taxpayers who would not ordinarily be interested in contributing to private schools may find the incentive too strong to ignore. Some states have seen an entire year’s allotment of tax credits claimed within days, or even hours, of being made available as wealthy taxpayers seek to capture their share of the profits associated with convoluted “neovoucher” systems. In effect, states that have encountered political or constitutional obstacles to spending public dollars on private schools have instead set up a system that allows wealthy taxpayers to enjoy a profit by facilitating such spending on the state’s behalf.

This report explains the workings, and problems, with state-level tax subsidies for private K-12 education. It also discusses how the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has exacerbated some of these problems by allowing taxpayers to claim federal charitable deductions even on private school contributions that were not truly charitable in nature. Finally, an appendix to this report provides additional detail on the specific K-12 private school tax subsidies made available by each state.

TYPES OF TAX CREDITS AND DEDUCTIONS

TYPES OF TAX CREDITS AND DEDUCTIONS

State-level tax provisions designed to subsidize private schools typically fall into one of two categories: those designed to facilitate the granting of private school scholarships, and those designed to offset private school expenses for families with children enrolled in such schools.

Tax subsidies for private school scholarships

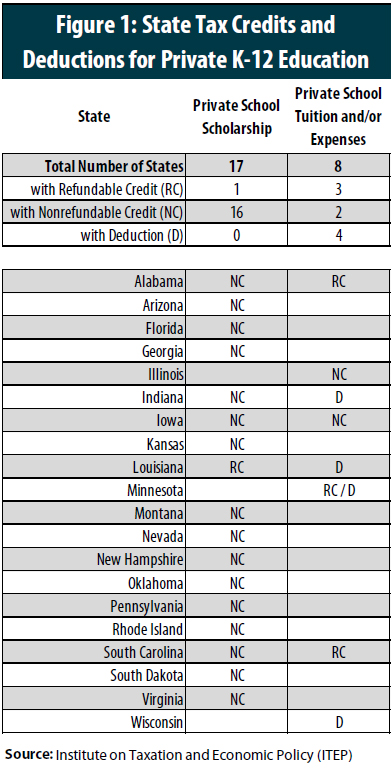

The most common, and most costly, tax subsidies for private education are intended to encourage businesses and/or individuals to contribute to organizations that distribute private school scholarships to qualifying students. Seventeen states offer tax credits designed to accomplish this purpose (see Figure 1), and their design varies considerably by state:

- Sixteen states offer nonrefundable scholarship credits, with some of these limited to a certain percentage of tax liability. In Georgia, for example, the scholarship credit cannot be used to offset more than 75 percent of income tax liability in a given year. Many of these credits can be “carried forward,” however, meaning that if a taxpayer does not owe enough tax to be able to use the credit this year, they can opt to claim some or all of the credit in later years. Louisiana is the only state where the scholarship credit is refundable—actually administered as a rebate—and therefore not tied to tax liability in any way.

- Scholarship tax credits range from 50 percent of the contribution amount (Indiana and Oklahoma) to 100 percent of the total contribution (Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Montana, Nevada, and South Carolina). Credits equal to 100 percent of the contribution are designed to allow taxpayers to redirect their tax payments toward private institutions at no cost to themselves. In practice, the actual tax benefits for credit recipients can sometimes even exceed the size of the donation. When the impact of state tax credits is combined with federal tax deductions (and sometimes state tax deductions as well), some taxpayers can actually turn a profit by making these so-called “donations”—an outcome described in detail below.

- Of the seventeen states that offer a scholarship credit, seven states only extend their credits and deductions to businesses (Florida, Kansas, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Dakota). Notably, four of these states do not levy personal income taxes. Among the ten states that allow both businesses and individuals to claim scholarship credits, four states (Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, and Virginia) allow businesses to claim a larger credit than individual taxpayers.

- While the scholarships funded by many of these tax credits are limited to low- or middle-income families, states such as Arizona, Georgia, and Montana offer at least some of the scholarships with no income restrictions.

- Some states place further limits on scholarship eligibility beyond income level, such as Pennsylvania where students must live in a “low-achieving” school zone and Kansas where students over six years of age must have been enrolled in a public school during the previous school year. These requirements have not always been strictly enforced, however, such as when the Georgia Department of Education signed off on parents “enrolling” their children in public schools to gain eligibility for the scholarship program, despite having no intention of allowing their children to attend the public schools in which they enrolled.[3]

- Aggregate limits on the size of these credits vary widely. Oklahoma’s credit is capped at just $3.4 million, for example, while Florida’s cap is set at almost $700 million for Fiscal Year 2018.[4]

Tax subsidies for private school tuition and/or expenses

Eight states offer tax credits or deductions to individuals to defray the cost of attending a private school (see Figure 1). The design of these tax subsidies varies considerably across states:

- Four states structure their subsidies as deductions, while five states offer tax credits (Minnesota offers both). Tax credit design also varies by state, with Illinois and Iowa allowing only “nonrefundable” credits that can offset, but not exceed, the taxpayer’s income tax bill. Alabama, Minnesota, and South Carolina offer “refundable” credits that are not dependent on earning enough to owe income tax.

- The private school expenses that qualify for the tax subsidy vary by state. Wisconsin’s deduction is limited to private school tuition, for example, while Indiana applies its deduction much more broadly to include not just tuition but also textbooks, fees, software, tutoring, and school supplies. Minnesota offers a deduction for both tuition and expenses, as well as a refundable credit that can only be applied against non-tuition expenses.

- Most state tax subsidies for private school expenses are available to all families regardless of income level or other characteristics. In South Carolina, however, the credit is only available to families with exceptional needs children. In Alabama the benefit is only available for children enrolled in a public school judged to be “failing.” And in Minnesota, the credit portion of the subsidy begins phasing out for families with incomes above $33,500.

- Each state uses a different formula for calculating the subsidy and imposes different limits on the size of the subsidy. Deductions range in size from $1,000 per dependent in Indiana to $10,000 per dependent (grades 9-12) in Wisconsin. Tax credits vary significantly as well, with more generous credits confined to states such as Alabama and South Carolina that, as mentioned above, only allow a small subset of students to claim them. The broader credits made available to all, or most, private school students vary from a maximum of $250 per dependent in Illinois and Iowa to $1,000 per dependent in Minnesota.

SUBSIDIES RUN AMOK: PROFITING FROM SCHOLARSHIP “DONATIONS”

In 2011, the IRS issued a memo indicating that taxpayers can claim a federal charitable deduction for private school scholarship donations even when those donations are also subsidized with a state tax credit.[5] While the memo states that it “may not be used or cited as precedent,” scholarship organizations in over dozen states have been advising their donors that their contributions are eligible for a federal tax deduction in addition to a state tax credit.[6] For some high-income taxpayers, this dual benefit can turn a scholarship “donation” into a profit-generating scheme where the total tax cut received significantly exceeds the size of the original donation. It should therefore come as little surprise that in some states, the entire allotment of available credits is often claimed just hours after state tax officials begin accepting applications.

A close look at South Carolina’s scholarship tax credit illustrates how this works. In the Palmetto State, taxpayers receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for any “donations” they make to certain nonprofit scholarship funding organizations—thereby making the donation essentially costless to the taxpayer. Assuming the taxpayer itemizes on their federal return, the immediate federal tax consequence of a donation is twofold: the taxpayer’s charitable deductions increase by the amount of the donation, and the taxpayer’s state income tax deduction falls by the amount of the tax credit they received. At first, this may appear to result in a wash for the taxpayer. But this is not always the case because in some instances, charitable deductions are more valuable than deductions for state income taxes paid.

At the federal level, one of these instances arises when taxpayers are subject to the individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).[7] The AMT is designed to ensure that taxpayers receiving generous tax breaks pay at least some minimum level of federal income tax. This is accomplished by denying certain tax breaks under AMT rules, including the deduction for state and local tax payments. Charitable donations, however, are still tax deductible under the AMT. So the ability to reclassify state income tax payments as charitable donations via a scholarship tax credit can be of significant benefit to taxpayers subject to the federal AMT—a group overwhelmingly comprised of taxpayers earning over $200,000 per year.[8]

The amount of benefit that can be realized by this reclassification depends on the amount of AMT owed and the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate under the AMT. Since marginal tax rates under the AMT range as high as 35 percent (after taking into account the AMT exemption phase-out), every dollar donated can potentially result in a federal tax cut of up to 35 cents. When combined with a dollar-for-dollar state tax credit, this means that a private school “donation” in South Carolina is better than costless, and can actually result in a risk-free return as high as 35 percent of every dollar “donated.”

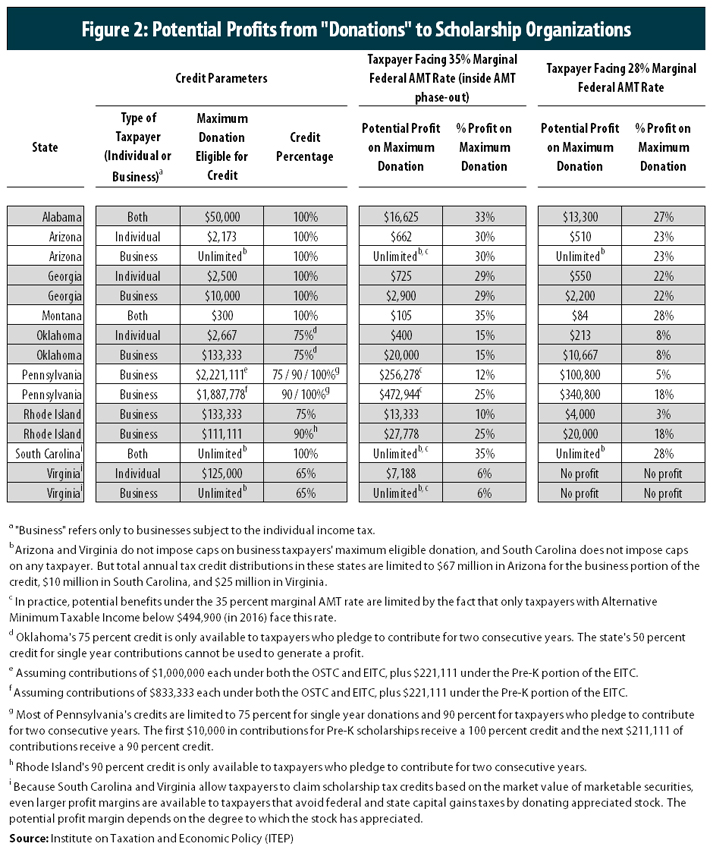

As shown in Figure 2, South Carolina’s 35 percent maximum return on scholarship contributions is one the most lucrative in the nation. Of the nine states where taxpayers can turn a profit by claiming federal and state tax benefits on the same contribution, only Montana matches South Carolina in offering potential profit margins of this size. However, Montana places a limit on the maximum donation that can be subsidized via a credit—the state’s $300 cap means that no taxpayer will receive more than $105 in profit in a given year.[9] The next highest profit margin (33 percent) is available in Alabama, where a much higher cap on eligible donations ($50,000) allows for profits as large as $16,625 per year. But South Carolina’s limits on tax credit claims are significantly looser than in either of these two states. The maximum size of any taxpayer’s credit in South Carolina is not subject to a firm cap, though taxpayers cannot receive credits in excess of 60 percent of their tax liability and the state will not distribute more than $10 million in total credits in a given year.

In the other six states where these tax credits can be paired with deductions to turn a profit, various tax rules (e.g., lower credit percentages, interactions with state itemized deduction rules, or the offsetting effects of state deductions for federal taxes paid) reduce the percentage yields to 30 percent or less.[10] Nonetheless, scholarship contributors with sufficient resources and enough knowledge of the federal AMT can still earn tens of thousands of dollars, or more, risk free in a single year. While a tax savvy business owner in Pennsylvania, for example, faces a lower profit margin (up to 25 percent) than in Alabama (up to 33 percent), Pennsylvania’s much higher cap on eligible donations allows for much larger potential profits. Under the right set of circumstances, a Pennsylvania business owner could reap hundreds of thousands of dollars in profit in a single year. Other states with particularly lucrative scholarship tax benefits include Arizona and Virginia, where business owners are eligible to receive tax credits without limit.[11]

Many scholarship organizations have realized that the profit-generating opportunities outlined above may appeal to donors that would not otherwise be interested in giving to private schools. One organization based in Georgia, for example, brags to potential donors that “you will end with more money than when you started”[12] Similarly, a tax lawyer in Alabama notes on her firm’s website that for taxpayers subject to the AMT, “donating” will actually “put money in your pocket.”[13] Private schools in Oklahoma and Pennsylvania have attempted to demonstrate the potential monetary gains of “donating” with hypothetical examples showing the financial returns of participating in their states’ programs.[14] And while they may not hold the program in high regard, a wealth management firm in Virginia notes that a taxpayer can enjoy a savings that is “more than their original donation” before going on to explain that “There is very little logic to the tax code. Even if you don’t agree with the law, you should take advantages of the tax benefits.”[15]

Wealthy taxpayers appear to have taken notice. In Georgia, the state’s entire allotment of $58 million in scholarship credits was claimed in a single day on January 1, 2016.[16] Later in the year, the same occurred within a matter of hours with regard to $67 million of credits in Arizona and $763,550 in credits in Rhode Island.[17] While taxpayer confidentiality laws generally conceal the magnitude of the benefits received by specific claimants, a journalist in South Carolina estimated that one savvy, anonymous taxpayer was able to reap a profit of between $100,000 and $638,000 in 2014 by stacking state, and possibly federal, deductions on top of scholarship tax credits.[18]

| Other Types of Tax Benefit Stacking

For taxpayers subject to the federal Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), federal charitable deductions are typically the most lucrative tax benefit that can be stacked on top of state scholarship tax credits. But there at least two other types of tax preferences that can be claimed alongside these credits in certain states. First, while most states prohibit taxpayers from claiming a state-level charitable deduction for donations that were also eligible for a state tax credit, three states (Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Virginia) actually allow this type of double dipping.* Since Oklahoma and Virginia do not allow taxpayers to deduct their state income tax payments from their state tax bills, converting non-deductible state tax payments into deductible charitable “donations” is a lucrative benefit. In Louisiana, where both state income tax payments and charitable donations are deductible, the benefit is smaller since only the portion of the donation that is not directly offset by a state tax credit triggers a tax benefit. Second, South Carolina and Virginia allow taxpayers to receive scholarship credits not just on cash donations, but also on the market value of any stock that they donate. This feature opens the door to additional profit opportunities for investors in these states. When a taxpayer donates stock that has appreciated in value, they receive not just the state tax credit and state and federal charitable deductions already described, but also the ability to avoid paying any state or federal tax on the capital gains income generated by that stock. When donating stock that has grown significantly in value since it was purchased, the tax benefit of this “donation” can far exceed the actual value of the stock donated.** * An ITEP review of those states where credits are available under the personal income tax found that donations subsidized via a state tax credit cannot also be taken as a state deduction for charitable contributions in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Montana, and South Carolina. Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island do not allow charitable deductions of any kind. ** The potential profit opportunities depend on the degree to which the stock has appreciated in value. For example, one hypothetical scenario circulated by a Catholic school and associated foundation in Roanoke, Virginia depicts a taxpayer enjoying a risk-free return of 19.4 percent on their “donation.” Roanoke Catholic School and McMahon Parater Foundation for Education. “Frequently Asked Questions: Education Improvement Scholarships Tax Credits.” March 2014. Available at:https://s3.amazonaws.com/roanokecatholicschool/roanokecatholicschool/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/EISTC-Donor-FAQ-3-14-Roanoke.pdf. |

OTHER ISSUES WITH PRIVATE SCHOOL TAX SUBSIDIES

Tax subsidies, or neovouchers, for private education are problematic both as tax policies and as education policy initiatives. Aside from the profit-making schemes just described, other issues associated with these programs include:

- Dubious educational benefits for recipients. Neovouchers are often touted as a way to improve educational outcomes by making it possible for families in areas with underperforming public schools to send their children to private schools instead. But there is little evidence that voucher programs of any kind have improved educational outcomes, and some recent studies suggest that students switching from public to private schools in Indiana and Louisiana actually scored lower on reading and math tests after making the switch.[19] Moreover, it can be difficult for parents to determine the actual quality of private schools in their area when those schools are not subject to the same accountability mechanisms as public schools. In Pennsylvania, for instance, schools benefiting from the state’s neovoucher program are exempt from state testing requirements and from reporting information on student progress or achievement.[20]

- Erosion of the public education system. While neovouchers are unlikely to improve educational outcomes for students moving to private schools, the negative impact on those students remaining in public schools is even clearer. Thirty neovouchers across twenty states are draining over $1 billion in public revenues from state coffers every year. Every dollar of revenue diverted toward private schools is revenue that cannot be invested in the public education system. Allowing certain taxpayers to opt out of funding an institution as fundamentally important as the nation’s public school system erodes the public’s level of investment in that institution—both literally and figuratively.

- Exaggerated cost savings. Neovoucher proponents often claim that state and local governments can realize substantial savings by moving students out of the public school system and into private schools. But while reductions in public school enrollment may reduce certain costs in certain circumstances, many costs are relatively fixed (maintenance, utilities, administration, etc.) and cannot be easily cut when students leave.[21] Moreover, when neovouchers are provided to families whose children would have been enrolled in private school anyway, the result is a loss of revenue without any actual reduction in enrollment or school district expenses. Research on Arizona’s tax credit program, for instance, found that most spending is directed toward students already enrolled in private schools.[22] And dramatic increases in funding for Arizona’s neovoucher programs do not appear to be leading to an exodus of public school students—enrollment in private schools has stagnated while public school enrollment has increased significantly.[23]

- Poorly targeted. Though frequently justified as a lifeline for disadvantaged children, the beneficiaries of neovoucher programs are often not low-income students. States such as Oklahoma and Pennsylvania allow upper-middle income families to benefit from scholarship subsidies, while other states such as Arizona, Georgia, and Montana allow even high-income families to benefit. Subsidies for tuition and other private school expenses are also typically made available regardless of income level. Making matters worse are the specific design decisions behind many of these tax subsidies. Tax deductions and nonrefundable credits are of no help to low-income families that earn too little to owe income tax. For that reason, even neovoucher advocates have suggested converting programs such as Wisconsin’s tuition deduction into refundable credits (though it is important to note that such a conversion would likely result in a dramatic increase the program’s overall cost).[24]

- Constitutional issues. Advocates of state subsidies for private education, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), often encourage states to administer their voucher programs via the tax code in order to circumvent state constitutional prohibitions on the public funding of religious schools.[25] According to ALEC, while lawmakers in eighteen states are constitutionally forbidden from offering direct vouchers for religious schools, tax credit neovouchers can be used to accomplish a nearly identical result in all but two of those states.[26] In some cases, these schools have curricula (such as biblical versions of science and history) or personnel policies (such as firing teachers if they enter a same-sex marriage or become pregnant outside of wedlock) that would be prohibited at a public institution and that raise questions about the appropriateness of directing public dollars toward these schools.[27] Arizona is perhaps the most well-known example of a state that succeeded in labeling its subsidies as “tax reductions” rather than “direct spending” in order to circumvent its own constitution. In 1998, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled 3-2 in Kotterman v. Killian that, unlike a traditional voucher, the state’s tax credit scholarships were not in violation of the Arizona Constitution in part because the credits are technically diverted to private schools before reaching the state’s coffers. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court reached a similar conclusion in a 5-4 ruling in Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn. But while neovouchers have so far been upheld on relatively narrow grounds, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan cut to the heart of the matter when she explained in her dissent that “cash grants and targeted tax breaks are means of accomplishing the same government objective—to provide financial support to select individuals or organizations.”

- Lack of budgetary oversight. Subsidies for private education provided via neovouchers are often not subject to the same budgetary oversight as ordinary spending on public education. Most notably, once a neovoucher is enacted into law it typically continues indefinitely without reexamination as part of the appropriations process. Moreover, those neovouchers not subject to an aggregate budgetary cap can grow significantly in cost without any action on the part of lawmakers. And even those neovouchers that are subject to caps sometimes see the cap structured in a way that allows for growth that far outpaces other areas of the budget, such as one of Arizona’s neovouchers for corporate taxpayers which is currently growing at a rate of 20 percent per year.[28]

CONCLUSION

Rather than enhancing educational opportunities, tax subsidies for private education often benefit students already enrolled in private schools while reducing the amount of state revenue available for public schools. Worse still, they undermine support for public education and give credence to the false notion that citizens who send their children to private schools have no obligation to support public schools.

On top of these problems, upper-income families that are able to exploit complex interactions between state and federal tax law can sometimes use these backdoor subsidies to generate a profit for themselves. This is made possible largely because the IRS currently allows taxpayers to claim a charitable deduction for private school contributions even when those contributions were fully reimbursed by the state and were therefore not truly charitable in nature. The resulting profits being collected by a small group of savvy taxpayers represent a drain on public revenue that ultimately benefits neither private nor public school students.

Neovouchers are an inefficient and opaque way of redirecting public dollars toward private schools. Nonetheless, these tax subsidies are being enacted in a growing number of states. It appears that their growing prevalence is partly attributable to their usefulness in sidestepping state constitutional restrictions, and partly because their lack of transparency helps avoid opposition from a public that generally opposes spending public funds on private schools.

APPENDIX: DETAILS ON STATE TAX SUBSIDIES FOR PRIVATE K-12 EDUCATION

Download Full Appendix as an Excel Spreadsheet

Read the Full Report Including Appendices in PDF

Note: This report was updated in May 2017 to acknowledge that South Carolina taxpayers can profit by donating stock that has appreciated in value, and that Louisiana’s tuition donation rebate does not allow taxpayers to turn a profit because the rebate is considered to be taxable income in the year in which it is received.

[1] ITEP calculation using data compiled in the appendix of this report.

[2] A 2013 poll found that 70 percent of the public opposes “allowing students and parents to choose a private school to attend at public expense.” Bushaw, William J. and Shane J. Lopez. “Which way do we go? The 45th annual PDK/Gallup Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward Public Schools.” September 2013. Available at: https://www.au.org/files/pdf_documents/2013_PDKGallup.pdf. Arizona may be the most prominent example of a state adopting a neovoucher program as a way to circumvent a constitutional prohibition on public funding of traditional vouchers. “Private School Tax Credits Divert Public Dollars for Private Benefits. Children’s Action Alliance. January 2016. Available at: http://azchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Private-School-Tax-Credit-brief-12-151.pdf. For additional discussion of the similarities between vouchers and neovouchers, see: Welner, Kevin. “’Neovouchers’: A Primer on Private School Tax Credits.” The Washington Post. March 3, 2013. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/03/03/neovouchers-a-primer-on-private-school-tax-credits/.

[3] Saul, Stephanie. “Public Money Finds Back Door to Private Schools.” The New York Times. May 21, 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/22/education/scholarship-funds-meant-for-needy-benefit-private-schools.html.

[4] “Florida Tax Credit Scholarships.” Florida Department of Education. Available at: http://www.fldoe.org/schools/school-choice/k-12-scholarship-programs/ftc/. Accessed October 7, 2016.

[5] Internal Revenue Service, Office of Chief Counsel. Memorandum Number 201105010. February 4, 2011. Available at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/1105010.pdf. Johnson, Sarah K. “Making a Profit From Charitable Donations in South Carolina.” State Tax Notes. August 25, 2014. Available at: http://www.taxhistory.org/www/features.nsf/Articles/4DEDCC0086226CF085257E1C004B1591?OpenDocument.

[6] An ITEP review found scholarship organizations advising donors that they can claim the federal charitable deduction in addition to state tax credits in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Montana, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.

[7] The corporate AMT faced by C corporations does not allow for the same type of gaming described in this report.

[8] IRS Statistics of Income data for Tax Year 2014 indicate that 82 percent of returns owing AMT, and 93 percent of dollar raised via the AMT, are associated with this group. Taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $500,000 per year are most likely to be affected by the AMT, with 61 percent of this group owing some amount under the levy. By comparison, 45 percent of taxpayers earning between $500,000 and $1 million owe some amount of AMT, as well as 19 percent of taxpayers earning over $1 million.

[9] The cap is $150 for individuals and $300 for married couples filing jointly.

[10] Scholarship credits in another seven states cannot be used to turn a profit because the credit percentage is too small (Indiana), the credit cannot be paired with a state charitable deduction (Iowa), or because the credit is not available to taxpayers subject to the personal income tax and thus the federal individual AMT does not apply (Florida, Kansas, Nevada, New Hampshire, and South Dakota).

[11] Arizona and Virginia do cap the overall amount of tax credits available statewide each year, however.

[12] “Request 2017 Tax Credit: Does Georgia Pay You to Donate?” Pay It Forward Scholarships. Available at: http://www.payitforwardscholarships.com/donate. Accessed on October 7, 2016.

[13] White, Ashley. “Save On Your Alabama Income Taxes and Reduce your Alternative Minimum Tax by Donating to a Scholarship Granting Organization.” Hall Albright Garrison & Associates. November 18, 2013.

[14] The Catholic Foundation of Oklahoma. “Catholic Schools: Opportunity Scholarship Fund.” Summer 2015. Available at: http://cfook.org/documents/links-resources-1/43-catholic-schools-opportunity-scholarship-fund-brochure-summer-2015-1/file. Cornerstone Christian Preparatory Academy. “Tax credit accounting details.” Available at: http://www.cornerstoneprep.net/ways-to-help/taxcreditinfo.cfm.

[15] Marotta, David John and Megan Russell. “Education Improvement Scholarship Tax Credits.” Marotta Wealth Management. August 16, 2015. Available at: http://www.emarotta.com/education-improvement-scholarship-tax-credits/.

[16] The Howard School. “Georgia Tax Credit.” Accessed October 7, 2016. Available at: https://www.howardschool.org/development/georgia-tax-credit.

[17] E-mail from Karen Jacobs, Arizona Department of Revenue. August 30, 2016. See also: Rhode Island Division of Taxation. “Tax Credits for Contributions to Scholarship Organizations.” Accessed October 7, 2016. Available at: http://www.tax.ri.gov/Credits/index.php.

[18] Slade, David. “S.C. tax rule creates a way to profit by funding private school scholarships.” The Post and Courier. July 13, 2014. Available at: http://www.postandcourier.com/article/20140713/PC05/140719981.

[19] For discussions of some of this literature, see: “Analysis of Indiana School Choice Scholarship Program.” Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. April 2015. Available at: http://www.ctbaonline.org/file/413/download?token=VPyo6T1H. Dynarski, Mark. “On negative effects of vouchers.” Evidence Speaks Reports, Vol 1, #18. Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/on-negative-effects-of-vouchers/.

[20] Herzenberg, Stephen. “No Accountability: Pennsylvania’s Track Record Using Tax Credits to Pay for Private and Religious School Tuition.” Keystone Research Center. April 2011. Available at: http://keystoneresearch.org/EITC-accountability.

[21] “Transforming Philadelphia’s Public Schools: Key findings and recommendations.” The Boston Consulting Group. August 2012. Available at: http://webgui.phila.k12.pa.us/uploads/v_/IF/v_IFJYCOr72CBKDpRrGAAQ/BCG-Summary-Findings-and-Recommendations_August_2012.pdf.

[22] Wilson, Glen Y., “The Equity Impact of Arizona’s Education Tax Credit Program: A Review of the First Three Years.” Arizona State University Education Policy Research Unit (http://epsl.asu.edu/epru/documents/EPRU%202002-110/epru-0203-110.htm)

[23] “Private School Tax Credits Divert Public Dollars for Private Benefits.” Children’s Action Alliance. January 2016. Available at: http://azchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Private-School-Tax-Credit-brief-12-151.pdf.

[24] “School Choice: Wisconsin—K-12 Private School Tuition Deduction.” EdChoice. Available at: https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/wisconsin-k-12-private-school-tuition-deduction/. Accessed October 7, 2016.

[25] Komer, Richard D. and Olivia Grady. “School Choice and State Constitutions: A Guide to Designing School Choice Programs.” A joint publication of the Institute for Justice and the American Legislative Exchange Council. Second Edition. September 2016. Available at: http://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/50-state-SC-report-2016-web.pdf.

[26] Ibid. The sixteen states allowing neovouchers but not ordinary vouchers include Alaska, California, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming. In Massachusetts and Michigan, both vouchers and neovouchers are unconstitutional. According to ALEC, Educational Savings Accounts are constitutional in Arizona though traditional vouchers are not.

[27] Saul, Stephanie. “Public Money Finds Back Door to Private Schools.” The New York Times. May 21, 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/22/education/scholarship-funds-meant-for-needy-benefit-private-schools.html. Garofoli, Joe. “Oakland Diocese requiring educators to conform to church teachings.” The San Francisco Chronicle. May 9, 2014. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Oakland-Diocese-requiring-educators-to-conform-to-5464492.php.

[28] The credit described here is designed to grow from $10 million in 2007 to $107 million in 2020. “Private School Tax Credits Divert Public Dollars for Private Benefits. Children’s Action Alliance. January 2016. Available at: http://azchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Private-School-Tax-Credit-brief-12-151.pdf.