Low- and middle-income working parents spend a significant portion of their income on child care. As the number of parents working outside of the home continues to rise, child care expenses have become an unavoidable and increasingly unaffordable expense. This policy brief examines state tax policy tools that can be used to make child care more affordable: a dependent care tax credit modeled after the federal program and a deduction for child care expenses.

How the Federal Dependent Care Credit Works

The federal government allows a nonrefundable income tax credit to help offset child care expenses. In 2017, single working parents (and two-earner married couples) with children 12 years of age or younger could claim a credit to partially offset up to $6,000 of child care expenses; low-income taxpayers could receive a credit of up to 35 percent of these expenses. In 2017, this meant a maximum credit of $2,100. The credit percentage gradually falls from 35 percent, for those with income under $15,000, to 20 percent of expenses for higher-income taxpayers. The credit drops by one percentage point for every $2,000 of income; taxpayers with incomes over $43,000 can claim the minimum credit of 20 percent of child care expenses. This “sliding scale” approach helps to target tax reductions somewhat more effectively to low-income taxpayers, although the credit is available to even the wealthiest taxpayers.

Options for State Dependent Care Tax Reductions

Nearly half of the states offer some form of state income tax break for families with dependent care expenses. Of those, the majority (22 states including the District of Columbia) model their state credit after the federal credit. This section looks at the various approaches states have taken—and assesses the usefulness of each approach in reducing the cost of low-income child care.

Credits vs. Deductions

The most basic choice to make in reducing taxes for dependent care is between a tax credit and a tax deduction. Almost all of the states that currently provide dependent care tax breaks use tax credits, which reduce taxes on a dollar-for-dollar basis. However, a few states allow income tax deductions for child care expenses. Deductions reduce taxable income on a dollar-for-dollar basis. In states with graduated income taxes (that is, income taxes that apply higher rates to higher-income taxpay-ers), deductions will be a better deal for wealthier taxpayers than for low-income parents. As shown in the accompanying hypothetical examples, a $3,000 child care deduction will be worth slightly more to a family earning $100,000 than to a family earning $20,000, while a tax credit based on the federal “sliding scale” rules will give a larger tax break to the lower-income family than to the wealthier taxpayer.

Limiting Eligibility by Income

Lawmakers must also choose whether to impose income eligibility limits. While the federal credit is available to taxpayers at all income levels, some states have chosen to restrict their credits to low- and middle-income taxpayers. Ten states currently have such an income limit, ranging from $30,160 in New Mexico to $100,000 in California and Oklahoma. By imposing income limits, states can reduce the cost of tax cuts for dependent care while targeting the benefits to those lower- and middle-income taxpayers for whom child care expenses are most burdensome.

As noted above, all states with child care credits use a “sliding scale” (modeled after the federal credit) that gives lower-income families a larger credit. But some states take additional steps to target tax cuts more precisely to low-income families. For example, the Nebraska credit is calculated as 100 percent of the federal credit at low income levels and 25 percent of the federal credit at higher income levels. This approach targets the benefits of the Nebraska credit much more efficiently to low- and middle-income parents than does the federal credit.

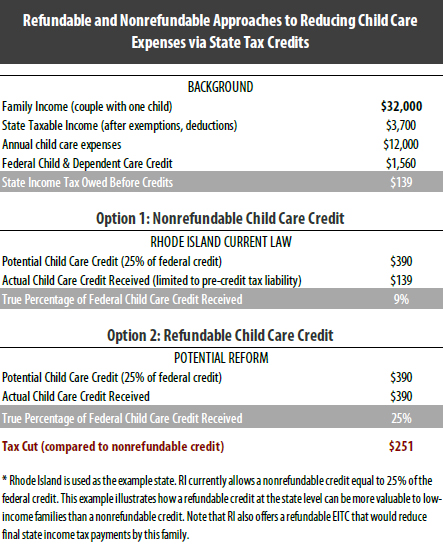

Refundability

For states allowing tax credits, possibly the most important policy choice is whether the credit should be refundable or non-refundable. A non-refundable tax credit can only be used to reduce income taxes to zero. A refundable credit, by contrast, does not depend on the amount of income taxes paid: if the credit amount exceeds your income tax liability, the excess amount is given as a refund. Refundability is an especially valuable feature in state credits for two reasons: first, low-income parents with substantial child care expenses and little or no income tax liability will receive little to no benefit from a non-refundable credit, and second, because the federal credit is nonrefundable, the state credit may be the only income-boosting tax cuts for child care expenses available to these families.

For states allowing tax credits, possibly the most important policy choice is whether the credit should be refundable or non-refundable. A non-refundable tax credit can only be used to reduce income taxes to zero. A refundable credit, by contrast, does not depend on the amount of income taxes paid: if the credit amount exceeds your income tax liability, the excess amount is given as a refund. Refundability is an especially valuable feature in state credits for two reasons: first, low-income parents with substantial child care expenses and little or no income tax liability will receive little to no benefit from a non-refundable credit, and second, because the federal credit is nonrefundable, the state credit may be the only income-boosting tax cuts for child care expenses available to these families.

Tying Benefits to Inflation

States must also decide whether to preserve the real value of these tax breaks by tying their value to inflation (See ITEP Brief, “Indexing Income Taxes for Inflation: Why It Matters” for more information). The impact of inflation means that (for example) the maximum $2,100 federal credit is worth slightly less every year. This problem affects both the income eligibility limits and the maximum credit amount. Very few states have taken steps to avoid this problem—which means that the value of this credit in reducing the cost of child care falls every year.

Are Tax Breaks the Best Approach to Making Child Care Affordable?

Tax credits are not the only way to reduce child care costs. Other policy tools are available, including direct subsidies to the families incurring these costs. States need to determine which approach works best for their budgeting process and spending priorities. That being said, the sizable, increasing portion of income average Americans spend on child care can and should be addressed at the state level.

Income tax breaks for dependent care have become an established practice. A majority of states now follow the federal government’s lead in providing income tax credits or deductions to make child care more affordable. As this policy brief has noted, some states do a better job than others in targeting tax cuts to the low- and middle-income taxpayers for whom child care represents a substantial expense. States seeking to provide targeted reductions to the cost of dependent care can do so most effectively by enacting a refundable tax credit with relatively low income limits.