For years, corporations stockpiled profits offshore to avoid paying U.S. taxes, with the sum growing to $2.6 trillion by 2017. Corporate apologists suggested that this cache was necessary because the corporate tax rate was too high, and they asserted that if the United States lowered its tax rate, corporations would repatriate those profits, pay taxes, invest in workers and we’d all win.

In 2016, then candidate Trump claimed there is as much as $5 trillion overseas and a tax break on those earnings would cause “all of this money to come back into our country” and “turn America into a magnet for new jobs.”

Based on previous experience with a repatriation holiday in 2004, critics argued that another repatriation tax break would be a major windfall to corporations that would enrich shareholders and accomplish little else.

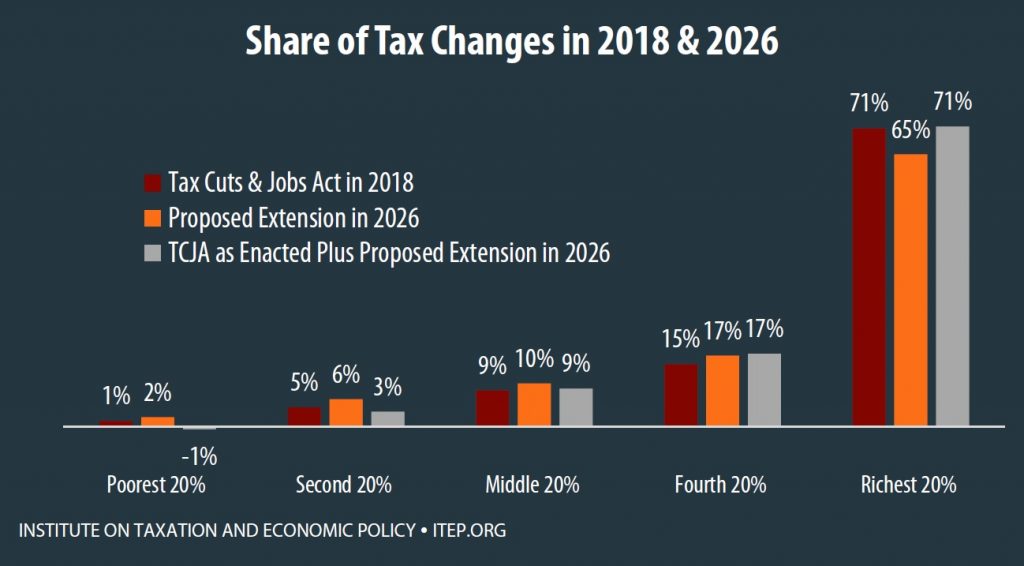

In the end, corporations and their allies got their way. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) included a provision that requires companies to pay a 15.5 percent tax rate on their accumulated offshore earnings held in cash and 8 percent on non-cash assets, representing a significant discount from the 35 percent rate they would have paid under previous law. As predicted, those riches are flowing back into corporate coffers and to wealthy shareholders. A new study by the Federal Reserve found that the evidence so far suggests that the new repatriation tax break has resulted in a surge in stock buybacks and little discernable impact in investment by its biggest beneficiaries, just as critics predicted.

Before TCJA, the tax code allowed companies to defer paying U.S. taxes on earnings held (on paper, at least) offshore. Corporations enjoyed this break as long as they did not technically repatriate these earnings to the United States. This created a huge incentive for companies to hoard their earnings offshore indefinitely. In fact, an ITEP report found that Fortune 500 companies avoided an estimated $752 billion in taxes on $2.6 trillion in earnings officially held offshore by mid-2017.

The ideal solution would have been to end tax deferral on these earnings and require corporations to pay what they owe on their offshore stockpile. This would have ended the incentive of companies to shift their profits offshore and raised a substantial amount of revenue. Instead, the TCJA provided companies a tax discount (the tax rates of 8 and 15.5 percent mentioned above) on previously unrepatriated offshore earnings and exempted future earnings from taxation upon repatriation. In other words, rather than paying the estimated $752 billion in taxes that they owed on their offshore earnings, companies were only required to pay $339 billion in taxes, meaning that this provision provided them with a $413 billion tax windfall.

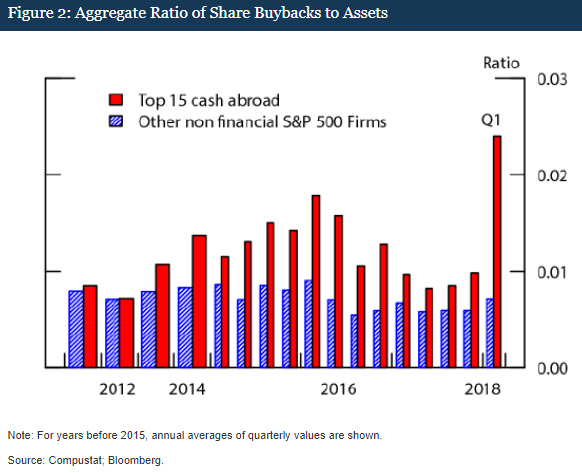

What did this tax windfall get the nation in terms of investment? Not very much according to the Federal Reserve’s analysis of the latest data. Its analysis found that U.S. firms repatriated $300 billion in the first quarter of 2018 and that this is driving the recent dramatic surge in stock buybacks by those same firms. In contrast, data show that companies repatriating substantial amounts from abroad did not have any discernable uptick in investment.

Companies were not particularly constrained from making investments in the United States under the old system, for several reasons. First, much of the money being held offshore for tax purposes was already invested in the United States. A Wall Street Journal investigation found, for instance, that 93 percent of the billions that Microsoft held “offshore” in tax haven subsidiaries were, in fact, invested in the U.S. financial system. Second, major multinational companies have easy access to credit, which they could use under the old system to make investments in the United States, while still holding a substantial amount of cash offshore as a tax accounting matter. For example, Apple used its offshore earnings as collateral to take out loans to pay for share buybacks and other investments in the United States, even as it held over $200 billion in earnings offshore to avoid taxes.

There are several steps lawmakers should take to fix the new incentives that the TCJA creates to shift future profits and even real jobs offshore. Lawmakers should push legislation to equalize the tax rate on foreign and domestic income, crack down on inversions, and create transparency by requiring companies to report financial information on a country-by-country basis. Taken together such legislation could end offshore tax avoidance once and for all.